All of these topics are ones I have addressed in my posts. Things are rapidly advancing and totally out of control. It is important to revisit these topics and bring them to light. To update those who are already aware and to bring awareness to those who are lagging behind.

It is encouraging to see so many people standing up for TRUTH and fighting back against the darkness. I pray that all who are on the Lord’s side will be provided the strength, courage, faith and POWER to continue to STAND until He comes.

You would have to be blind not to see that the world in which we live is on the HIGHWAY TO HELL. Society is rapidly falling deeper and deeper into Chaotic, Disastrous, Destructive Mayhem. Every day our news is full of totaly insanity. Humanity seems to have lost all sense of itself. That sounds impossible in a world where everything is focused on SELF. None the less it is true to our great dismay.

The world has gone completely TOPSY TURVY. Scientists keep telling us the earth is reversing on its axis. I don’t believe that because we live on a flat, stationary earth. BUT, our world is definitely being turned upside down just exactly as the bible predicted. Good is now considered EVIL and EVIL is now considered GOOD. Right is Wrong and Wrong is Right. Black is the NEW WHITE. THERE ARE EITHER NO GENDERS OR OVER 100 GENDERS, but MEN and WOMEN go longer exist. Pedophiles teach our children perverted behaviors and sexual acts the schools paid for by our taxes. Farmers are not allowed to farm. Ranchers are not allowed to raise stock. They are feeding us food stuffs created in test tubes and polluting our water with all manner of chemicals. Doctors are today’s pushers. Our jails are filled with innocent people held without trial. The police are trained to kill. Rioters, looters and shooters fill our streets. Weather has become a weapon of mass destruction. Cars are about to be outlawed and we are being forced into TINY LIVING SPACES. They have completely killed our economy, there are no jobs. Growing your own food is illegal already in many places. Our voting system has been completely corrupted and those who are running our governments are insane!!

Does all that not make you sit up and say, “WHAT HAPPENED? HOW DID WE GET HERE?”

spacer

If you have not seen my posts on this topic, you can find some of them here:

SCIENCE – The Deception is designed to destroy our faith in the WORD of God

Science – The MagicK that will DESTROY Mankind

Gifts from the Fallen – Part 2 – Sacred Arts, Sciences and Crafts

Do You Believe in Magick? Part 16 – Science is MAGICK/WITCHCRAFT

AI God – Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4

Satan’s Latest Weapon in the Battle for Your Mind– Part 1; Part 2; Part 3

WHOSE REPORT WILL YOU BELIEVE? DON’T FALL FOR THEIR LIES.

spacer

| BEAST TECHNOLOGY IS RAPIDLY BUILDING A REPLACEMENT TO ALL CURRENT RELIGIONS

The future of artificial intelligence is neither utopian nor dystopian—it’s something much more interesting. This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here. Miracles can be perplexing at first, and artificial intelligence is a very new miracle. “We’re creating God,” the former Google Chief Business Officer Mo Gawdat recently told an interviewer. “We’re summoning the demon,” Elon Musk said a few years ago, in a talk at MIT. In Silicon Valley, good and evil can look much alike, but on the matter of artificial intelligence, the distinction hardly matters. Either way, an encounter with the superhuman is at hand. Early artificial intelligence was simple: Computers that played checkers or chess, or that could figure out how to shop for groceries. But over the past few years, machine learning—the practice of teaching computers to adapt without explicit instructions—has made staggering advances in the subfield of Natural Language Processing, once every year or so. Even so, the full brunt of the technology has not arrived yet. You might hear about chatbots whose speech is indistinguishable from humans’, or about documentary makers re-creating the voice of Anthony Bourdain, or about robots that can compose op-eds. But you probably don’t use NLP in your everyday life. Or rather: If you are using NLP in your everyday life, you might not always know. Unlike search or social media, whose arrivals the general public encountered and discussed and had opinions about, artificial intelligence remains esoteric—every bit as important and transformative as the other great tech disruptions, but more obscure, tucked largely out of view.

spacer But the confusion surrounding the miracles of AI doesn’t mean that the miracles aren’t happening. It just means that they won’t look how anybody has imagined them. Arthur C. Clarke famously said that “technology sufficiently advanced is indistinguishable from magic.” Magic is coming, and it’s coming for all of us. All technology is, in a sense, sorcery. A stone-chiseled ax is superhuman. No arithmetical genius can compete with a pocket calculator. Even the biggest music fan you know probably can’t beat Shazam. But the sorcery of artificial intelligence is different. When you develop a drug, or a new material, you may not understand exactly how it works, but you can isolate what substances you are dealing with, and you can test their effects. Nobody knows the cause-and-effect structure of NLP. That’s not a fault of the technology or the engineers. It’s inherent to the abyss of deep learning. I recently started fooling around with Sudowrite, a tool that uses the GPT-3 deep-learning language model to compose predictive text, but at a much more advanced scale than what you might find on your phone or laptop. Quickly, I figured out that I could copy-paste a passage by any writer into the program’s input window and the program would continue writing, sensibly and lyrically. I tried Kafka. I tried Shakespeare. I tried some Romantic poets. The machine could write like any of them. In many cases, I could not distinguish between a computer-generated text and an authorial one. I was delighted at first, and then I was deflated. I was once a professor of Shakespeare; I had dedicated quite a chunk of my life to studying literary history. My knowledge of style and my ability to mimic it had been hard-earned. Now a computer could do all that, instantly and much better. A few weeks later, I woke up in the middle of the night with a realization: I had never seen the program use anachronistic words. I left my wife in bed and went to check some of the texts I’d generated against a few cursory etymologies. My bleary-minded hunch was true: If you asked GPT-3 to continue, say, a Wordsworth poem, the computer’s vocabulary would never be one moment before or after appropriate usage for the poem’s era. This is a skill that no scholar alive has mastered. This computer program was, somehow, expert in hermeneutics: interpretation through grammatical construction and historical context, the struggle to elucidate the nexus of meaning in time. The details of how this could be are utterly opaque. NLP programs operate based on what technologists call “parameters”: pieces of information that are derived from enormous data sets of written and spoken speech, and then processed by supercomputers that are worth more than most companies. GPT-3 uses 175 billion parameters. Its interpretive power is far beyond human understanding, far beyond what our little animal brains can comprehend. Machine learning has capacities that are real, but which transcend human understanding: the definition of magic. This unfathomability poses a spiritual conundrum. But it also poses a philosophical and legal one. In an attempt to regulate AI, the European Union has proposed transparency requirements for all machine-learning algorithms. Eric Schmidt, the ex-CEO of Google, noted that such requirements would effectively end the development of the technology. The EU’s plan “requires that the system would be able to explain itself. But machine-learning systems cannot fully explain how they make their decisions,” he said at a 2021 summit. You use this technology to think through what you can’t; that’s the whole point. Inscrutability is an industrial by-product of the process. My little avenue of literary exploration is my own, and neither particularly central nor relevant to the unfolding power of artificial intelligence (although I can see, off the top of my head, that the tech I used will utterly transform education, journalism, film, advertising, and publishing). NLP has made its first strides into visual arts too—Dall-E 2 has now created a limitless digital museum of AI-generated images drawn from nothing more than prompts. Others have headed into deeper waters. Schmidt recently proposed a possible version of our AI future in a conversation with this magazine’s executive editor, Adrienne LaFrance: “If you imagine a child born today, you give the child a baby toy or a bear, and that bear is AI-enabled,” he said. “And every year the child gets a better toy. Every year the bear gets smarter, and in a decade, the child and the bear who are best friends are watching television and the bear says, ‘I don’t really like this television show.’ And the kid says, ‘Yeah, I agree with you.’” Schmidt’s vision does not yet exist. But in late 2020, Microsoft received a patent for chatbots that bring back the dead, using inputs from “images, voice data, social media posts, electronic messages, written letters, etc.” to “create or modify a special index in the theme of the specific person’s personality.” Soon after, a company called Project December released a version of just such a personality matrix. It created bots such as William, which speaks like Shakespeare, and Samantha, a rather bland female companion. But it also allowed mourners to re-create dead loved ones. An article in the San Francisco Chronicle told the story of Joshua Barbeau, who created a bot of his deceased fiancée, Jessica Pereira. Their conversation started like this:

Barbeau’s conversation with Jessica continued for several months. His experience of Project December was far from perfect—there were glitches, there was nonsense, the bot’s architecture decayed—but Barbeau really felt like he was encountering some kind of emanation of his dead fiancée. The technology, in other words, came to occupy a place formerly reserved for mediums, priests, and con artists. “It may not be the first intelligent machine,” Jason Rohrer, the designer of Project December, has said, “but it kind of feels like it’s the first machine with a soul.” What we are doing is teaching computers to play every language game that we can identify. We can teach them to talk like Shakespeare, or like the dead. We can teach them to grow up alongside our children. We can certainly teach them to sell products better than we can now. Eventually, we may teach them how to be friends to the friendless, or doctors to those without care. PaLM, Google’s latest foray into NLP, has 540 billion parameters. According to the engineers who built it, it can summarize text, reason through math problems, use logic in a way that’s not dissimilar from the way you and I do. These engineers also have no idea why it can do these things. Meanwhile, Google has also developed a system called Player of Games, which can be used with any game at all—games like Go, exercises in pure logic that computers have long been good at, but also games like poker, where each party has different information. This next generation of AI can toggle back and forth between brute computation and human qualities such as coordination, competition, and motivation. It is becoming an idealized solver of all manner of real-world problems previously considered far too complicated for machines: congestion planning, customer service, anything involving people in systems. These are the extremely early green shoots of an entire future tech ecosystem: The technology that contemporary NLP derives from was only published in 2017. And if AI harnesses the power promised by quantum computing, everything I’m describing here would be the first dulcet breezes of a hurricane. Ersatz humans are going to be one of the least interesting aspects of the new technology. This is not an inhuman intelligence but an inhuman capacity for digital intelligence. An artificial general intelligence will probably look more like a whole series of exponentially improving tools than a single thing. It will be a whole series of increasingly powerful and semi-invisible assistants, a whole series of increasingly powerful and semi-invisible surveillance states, a whole series of increasingly powerful and semi-invisible weapons systems. The world would change; we shouldn’t expect it to change in any kind of way that you would recognize. Our AI future will be weird and sublime and perhaps we won’t even notice it happening to us. The paragraph above was composed by GPT-3. I wrote up to “And if AI harnesses the power promised by quantum computing”; machines did the rest. Technology is moving into realms that were considered, for millennia, divine mysteries. AI is transforming writing and art—the divine mystery of creativity. It is bringing back the dead—the divine mystery of resurrection. It is moving closer to imitations of consciousness—the divine mystery of reason. It is piercing the heart of how language works between people—the divine mystery of ethical relation. All this is happening at a raw moment in spiritual life. The decline of religion in America is a sociological fact: Religious identification has been in precipitous decline for decades. Silicon Valley has offered two replacements: the theory of the simulation, which postulates that we are all living inside a giant computational matrix, and of the singularity, in which the imminent arrival of a computational consciousness will reconfigure the essence of our humanity. Like all new faiths, the tech religions cannibalize their predecessors. The simulation is little more than digital Calvinism, with an omnipotent divinity that preordains the future. The singularity is digital messianism, as found in various strains of Judeo-Christian eschatology—a pretty basic onscreen Revelation. Both visions are fundamentally apocalyptic. Stephen Hawking once said that “the development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race.” Experts in AI, even the men and women building it, commonly describe the technology as an existential threat. But we are shockingly bad at predicting the long-term effects of technology. (Remember when everybody believed that the internet was going to improve the quality of information in the world?) So perhaps, in the case of artificial intelligence, fear is as misplaced as that earlier optimism was. AI is not the beginning of the world, nor the end. It’s a continuation. The imagination tends to be utopian or dystopian, but the future is human—an extension of what we already are. My own experience of using AI has been like standing in a river with two currents running in opposite directions at the same time: Alongside a vertiginous sense of power is a sense of humiliating disillusionment. This is some of the most advanced technology any human being has ever used. But of 415 published AI tools developed to combat COVID with globally shared information and the best resources available, not one was fit for clinical use, a recent study found; basic errors in the training data rendered them useless. In 2015, the image-recognition algorithm used by Google Photos, outside of the intention of its engineers, identified Black people as gorillas. The training sets were monstrously flawed, biased as AI very often is. Artificial intelligence doesn’t do what you want it to do. It does what you tell it to do. It doesn’t see who you think you are. It sees what you do. The gods of AI demand pure offerings. Bad data in, bad data out, as they say, and our species contains a great deal of bad data. Artificial intelligence is returning us, through the most advanced technology, to somewhere primitive, original: an encounter with the permanent incompleteness of consciousness. Religions all have their approaches to magic—transubstantiation for Catholics, the lost temple for the Jews. Even in the most scientific cultures, there is always the beyond. The acropolis in Athens was a fortress of wisdom, a redoubt of knowledge and the power it brings—through agriculture, through military victory, through the control of nature. But if you wanted the inchoate truth, you had to travel the road to Delphi. A fragment of humanity is about to leap forward massively, and to transform itself massively as it leaps. Another fragment will remain, and look much the same as it always has: thinking meat in an inconceivable universe, hungry for meaning, gripped by fascination. The machines will leap, and the humans will look. They will answer, and we will question. The glory of what they can do will push us closer and closer to the divine. They will do things we never thought possible, and sooner than we think. They will give answers that we ourselves could never have provided. But they will also reveal that our understanding, no matter how great, is always and forever negligible. Our role is not to answer but to question, and to let our questioning run headlong, reckless, into the inarticulate. spacer |

A terrifying AI-generated woman is lurking in the abyss of latent space

“Loab is the last face you see before you fall off the edge.”

Image Credits: Supercomposite (collaged by TechCrunch)

There’s a ghost in the machine. Machine learning, that is.

We are all regularly amazed by AI’s capabilities in writing and creation, but who knew it had such a capacity for instilling horror? A chilling discovery by an AI researcher finds that the “latent space” comprising a deep learning model’s memory is haunted by least one horrifying figure — a bloody-faced woman now known as “Loab.”

(Warning: Disturbing imagery ahead.)

Loab was discovered — encountered? summoned? — by a musician and artist who goes by Supercomposite on Twitter (this article originally used her name but she said she preferred to use her handle for personal reasons, so it has been substituted throughout). She explained the Loab phenomenon in a thread that achieved a large amount of attention for a random creepy AI thing, something there is no shortage of on the platform, suggesting it struck a chord (minor key, no doubt).

Supercomposite was playing around with a custom AI text-to-image model, similar to but not DALL-E or Stable Diffusion, and specifically experimenting with “negative prompts.”

Ordinarily, you give the model a prompt, and it works its way toward creating an image that matches it. If you have one prompt, that prompt has a “weight” of one, meaning that’s the only thing the model is working toward.

You can also split prompts, saying things like “hot air balloon::0.5, thunderstorm::0.5” and it will work toward both of those things equally — this isn’t really necessary, since the language part of the model would also accept “hot air balloon in a thunderstorm” and you might even get better results.

But the interesting thing is that you can also have negative prompts, which causes the model to work away from that concept as actively as it can.

Minus world

This process is far less predictable, because no one knows how the data is actually organized in what one might anthropomorphize as the “mind” or memory of the AI, known as latent space.

“The latent space is kind of like you’re exploring a map of different concepts in the AI. A prompt is like an arrow that tells you how far to walk in this concept map and in which direction,” Supercomposite told me.

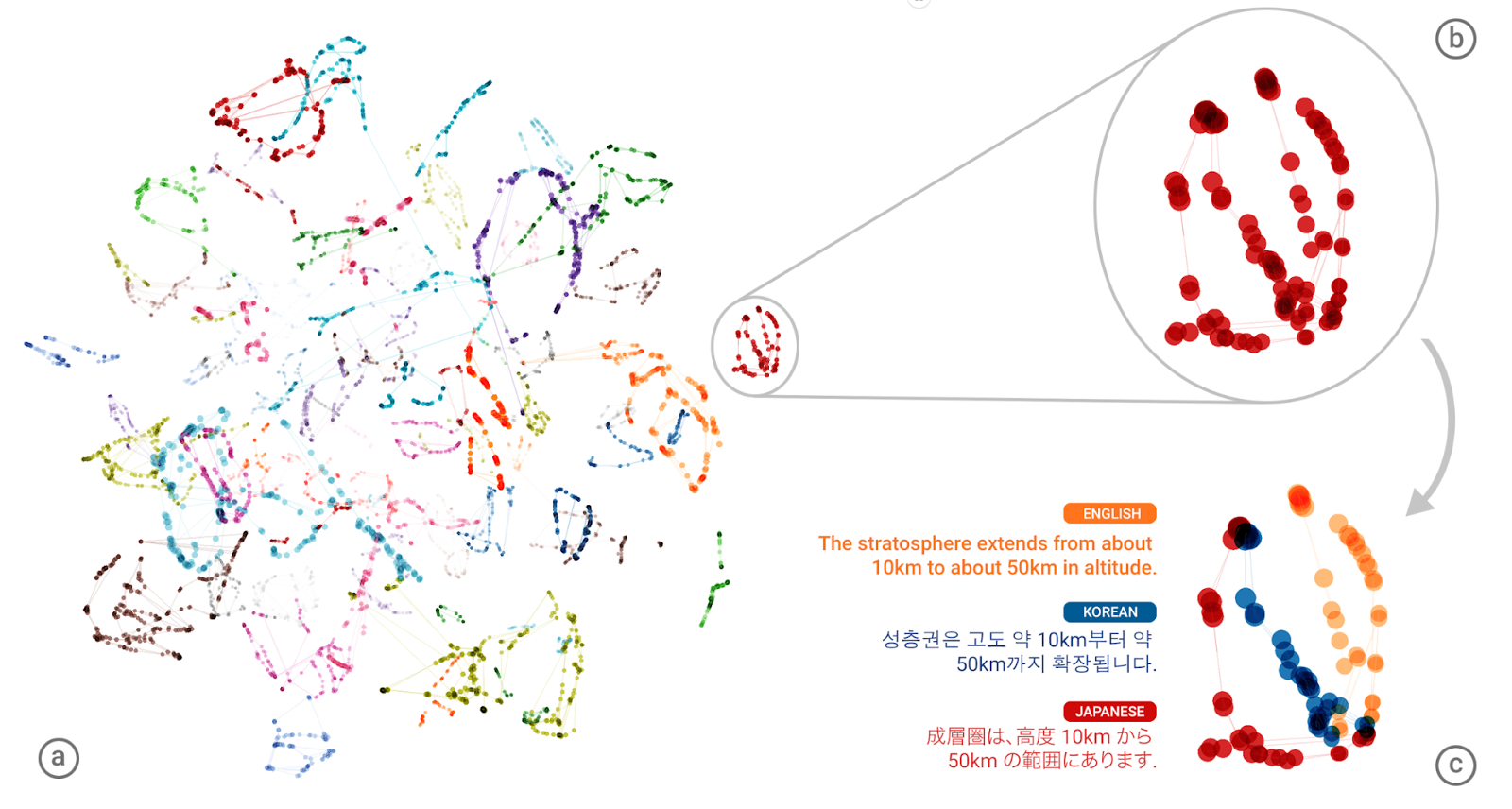

Here’s a helpful rendering of a much, much simpler latent space in an old Google translation model working on a single sentence in multiple languages:

The latent space of a system like DALL-E is orders of magnitude larger and more complex, but you get the general idea. If each dot here was a million spaces like this one it’s probably a bit more accurate. Image Credits: Google

“So if you prompt the AI for an image of ‘a face,’ you’ll end up somewhere in the middle of the region that has all the of images of faces and get an image of a kind of unremarkable average face,” she said. With a more specific prompt, you’ll find yourself among the frowning faces, or faces in profile, and so on. “But with negatively weighted prompt, you do the opposite: You run as far away from that concept as possible.”

But what’s the opposite of “face”? Is it the feet? Is it the back of the head? Something faceless, like a pencil? While we can argue it amongst ourselves, in a machine learning model it was decided during the process of training, meaning however visual and linguistic concepts got encoded into its memory, they can be navigated consistently — even if they may be somewhat arbitrary.

Image Credits: Supercomposite

We saw a related concept in a recent AI phenomenon that went viral because one model seemed to reliably associate some nonsense words with birds and insects. But it wasn’t that DALL-E had a “secret language” in which “Apoploe vesrreaitais” means birds — it’s just that the nonsense prompt basically had it throwing a dart at a map of its mind and drawing whatever it lands nearby, in this case birds because the first word is kind of similar to some scientific names. So the arrow just pointed generally in that direction on the map.

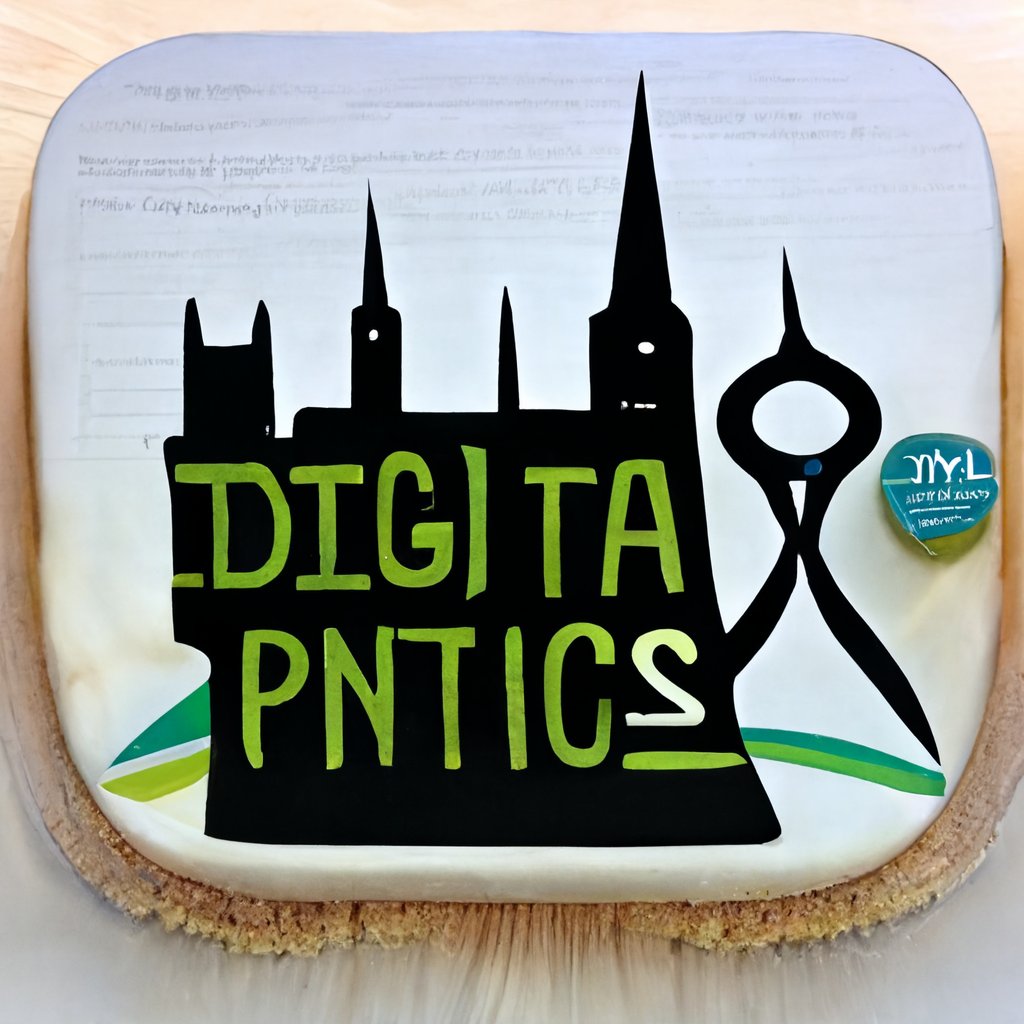

Supercomposite was playing with this idea of navigating the latent space, having given the prompt of “Brando::-1,” which would have the model produce whatever it thinks is the very opposite of “Brando.” It produced a weird skyline logo with nonsense but somewhat readable text: “DIGITA PNTICS.”

Weird, right? But again, the model’s organization of concepts wouldn’t necessarily make sense to us. Curious, Supercomposite wondered it she could reverse the process. So she put in the prompt: “DIGITA PNITICS skyline logo::-1.” If this image was the opposite of “Brando,” perhaps the reverse was true too and it would find its way to, perhaps, Marlon Brando?

Instead, she got this:

Image Credits: Supercomposite

Over and over she submitted this negative prompt, and over and over the model produced this woman, with bloody, cut or unhealthily red cheeks and a haunting, otherworldly look. Somehow, this woman — whom Supercomposite named “Loab” for the text that appears in the top-right image there — reliably is the AI model’s best guess for the most distant possible concept from a logo featuring nonsense words.

What happened? Supercomposite explained how the model might think when given a negative prompt for a particular logo, continuing her metaphor from before.

“You start running as fast as you can away from the area with logos,” she said. “You maybe end up in the area with realistic faces, since that is conceptually really far away from logos. You keep running, because you don’t actually care about faces, you just want to run as far away as possible from logos. So no matter what, you are going to end up at the edge of the map. And Loab is the last face you see before you fall off the edge.”

Preternaturally persistent

Image Credits: Supercomposite

Negative prompts don’t always produce horrors, let alone so reliably. Anyone who has played with these image models will tell you it can actually be quite difficult to get consistent results for even very straightforward prompts.

Put in one for “a robot standing in a field” four or 40 times and you may get as many different takes on the concept, some hardly recognizable as robots or fields. But Loab appears consistently with this specific negative prompt, to the point where it feels like an incantation out of an old urban legend.

You know the type: “Stand in a dark bathroom looking at the mirror and say ‘Bloody Mary’ three times.” Or even earlier folk instructions of how to reach a witch’s abode or the entrance to the underworld: Holding a sprig of holly, walk backward 100 steps from a dead tree with your eyes closed.

“DIGITA PNITICS skyline logo::-1” isn’t quite as catchy, but as magic words go the phrase is at least suitably arcane. And it has the benefit of working. Only on this particular model, of course — every AI platform’s latent space is different, though who knows if Loab may be lurking in DALL-E or Stable Diffusion too, waiting to be summoned.

In fact, the incantation is strong enough that Loab seems to infect even split prompts and combinations with other images.

“Some AIs can take other images as prompts; they basically can interpret the image, turning it into a directional arrow on the map just like they treat text prompts,” explained Supercomposite. “I used Loab’s image and one or more other images together as a prompt … she almost always persists in the resulting picture.”

Sometimes more complex or combination prompts treat one part as more of a loose suggestion. But ones that include Loab seem not just to veer toward the grotesque and horrifying, but to include her in a very recognizable fashion. Whether she’s being combined with bees, video game characters, film styles or abstractions, Loab is front and center, dominating the composition with her damaged face, neutral expression and long dark hair.

It’s unusual for any prompt or imagery to be so consistent — to haunt other prompts the way she does. Supercomposite speculated on why this might be.

“I guess because she is very far away from a lot of concepts and so it’s hard to get out of her little spooky area in latent space. The cultural question, of why the data put this woman way out there at the edge of the latent space, near gory horror imagery, is another thing to think about,” she said.

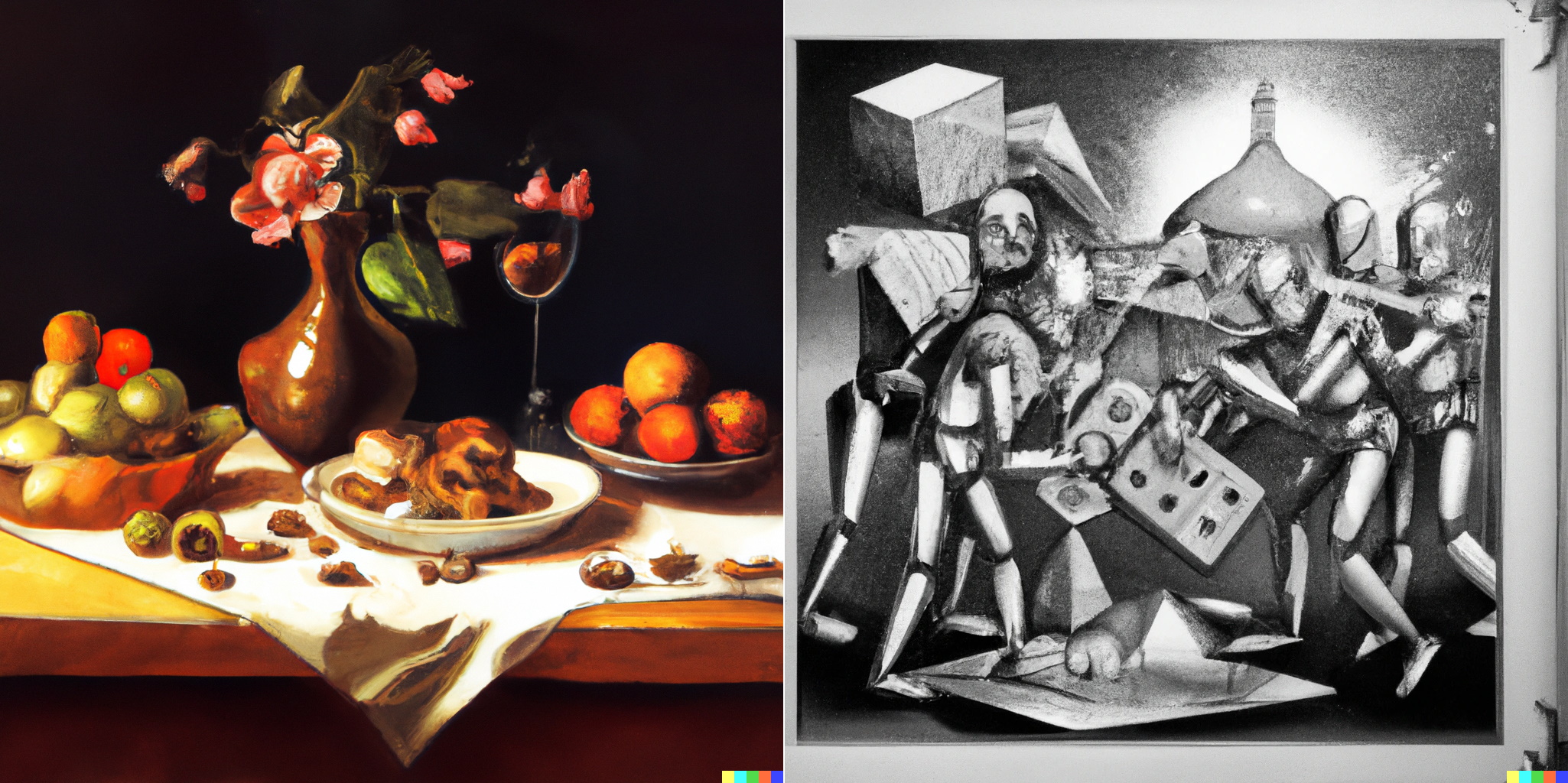

Although it’s an oversimplification, latent space really is like a map, and the prompts like directions for navigating it — and the system draws whatever ends up being around where it’s asked to go, whether it’s well-trodden ground like “still life by a Dutch master” or a synthesis of obscure or disconnected concepts: “robots battle aliens in a cubist etching by Dore.” As you can see:

Image Credits: TechCrunch / DALL-E

A purely speculative explanation of why Loab exists has to do with how that map is laid out. As Supercomposite suggested, it’s likely that, simply due to the fact that company logos and horrific, scary imagery are very far from one another conceptually.

A negative prompt doesn’t mean “take 10 data steps in the other direction,” it means keep going as far as you can, and it’s more than possible that images at the farthest reaches of an AI’s latent space have more extreme or uncommon values. Wouldn’t you organize it that way, with stuff that has lots of commonalities or cross-references in the “center,” however you define that — and weird, wild stuff that’s rarely relevant out at the “edge”?

Therefore negative prompts may act like a way to explore the frontier of the AI’s mind map, skimming the concepts it deems too outlandish to store among prosaic concepts like happy faces, beautiful landscapes or frolicking pets.

The dark forest of the AI subconscious

Image Credits: Devin Coldeway

The unnerving fact is no one really understands how latent spaces are structured or why. There is of course a great deal of research on the subject, and some indications that they are organized in some ways like how our own minds are — which makes sense, since they were more or less built in imitation of them. But in other ways they have totally unique structures connecting across vast conceptual distances.

To be clear, it’s not as if there is some clutch of images specifically of Loab waiting to be found — they’re definitely being created on the fly, and Supercomposite told me there’s no indication the digital cryptid is based on any particular artist or work. That’s why latent space is latent! These images emerged from a combination of strange and terrible concepts that all happen to occupy the same area in the model’s memory, much like how in the Google visualization earlier, languages were clustered based on their similarity.

From what dark corner or unconscious associations sprang Loab, fully formed and coherent? We can’t yet trace the path the model took to reach her location; a trained model’s latent space is vast and impenetrably complex.

The only way we can reach the spot again is through the magic words, spoken while we step backward through that space with our eyes closed, until we reach the witch’s hut that can’t be approached by ordinary means. Loab isn’t a ghost, but she is an anomaly, yet paradoxically she may be one of an effectively infinite number of anomalies waiting to be summoned from the farthest, unlit reaches of any AI model’s latent space.

It may not be supernatural … but sure as hell ain’t natural.

Scientism: Is Worship of Science Replacing Religion?

In a January 1931 debate with writer G.K. Chesterton, famed “monkey trial” lawyer Clarence Darrow essentially stated that science had refuted religion. In fact, his implication was that science could replace religion.

It may seem ironic that the debate’s topic was “Will the World Return to Religion?” and that now, 90 years later, we’re lamenting how people are leaving what they in 1931 supposedly had already left. That is to say, a recent Gallup poll showed that for the first time in American history, less than 50 percent of the population holds membership in a house of worship.

The National Pulse opened with this statistic in a Sunday essay entitled “New American Divinity — Part I: Scientism.” Writer Noelle Garnier discusses how faith in science appears to be supplanting faith in God and posits that the coronavirus situation — with scientists such as Anthony Fauci front and center appearing as secular saviors — may spur a further conversion to “scientism.”

After listing some of science’s achievements, Garnier writes that these “‘miracles’ aren’t spurring mass conversion to monotheistic faiths, but religious conversions — indeed, tectonic shifts — are happening, as Gallup’s data indicate.” She states that the COVID-19 pandemic “seems to have been” a “mass conversion event to the ‘new divinity.’”

As evidence, Garnier writes, referencing a Pew Research Center survey via a link, that the “COVID-19 outbreak raised the authority of medical scientists — who appear to hold the confidence of most Americans… — to quasi-religious dimensions.”

While I myself have written of how the China virus response has taken on religious flavor and fervor, with the dogma-driven COVID Ritual (e.g., masking, social distancing), Garnier’s analysis is likely flawed. First, Pew points out that the authority of medical scientists has risen mainly among Democrats. Perhaps more significantly, the survey was conducted last May, at the height of the outbreak and SARS-CoV-2 fears, when people wanted to believe in the government “experts.”

A better way to frame what’s occurring is that people are losing faith in all our institutions, inclusive of religion and perhaps science. Some call this a Third Turning period of history.

Nonetheless, the notion that science can replace religion is not uncommon today, nor is the tendency to turn science into a “religion”: scientism. Given this, the matter warrants examination, and we can start by defining the terms.

“‘Science is an open-ended exploration of reality based on logical thinking about empirical observations,’” related Psychology Today, quoting psychologist Imants Baruss. “Scientism is the adherence to a materialist version of reality that confines investigation to those sorts of things that are permitted by materialism.”

Scientism-oriented sentiments are everywhere. For example, Garnier quotes basketball coach Stan Van Gundy as tweeting, “It is far more important that our government leaders believe in science than that they believe in god [sic].”

Then there’s astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, best known for playing a scientist on TV, who said, “The good thing about Science is that it’s true, whether or not you believe in it.” (That is a TOTAL LIE. Most if not all Scientific Theories will NEVER be Proven. That is why they call them THEORIES. That definition Tyson gave is the definition of ABSOLUTE TRUTH…and cannot be applied to SCIENCE by ANY STRETCH OF THE IMAGINATION.)

This is an odd statement. If someone said, “The good thing about Religion is that it’s true, whether or not you believe in it,” you might point out that there’s good and bad religion. Was the religion of the human-sacrificing Aztecs true?

Likewise, is there not good and bad science? Was Lysenkoism true? Tyson may respond that pseudo-science isn’t “Science.” But often the former is called the latter until it’s exposed as pseudo-science. As to this, note that “mainstream” science’s pronouncements have often proven to be wrong.

But the main problem with scientism involves a deeper matter. When Gundy prioritized belief in “science” over belief in God, perhaps implied is that the two are competing spheres. Yet it’s not just that they’re actually in a way complementary in that they both involve the search for Truth (via different means), but that science can’t be directed only toward the good without what “religion” provides. In fact, expecting good science without the direction of good religion/philosophy is like expecting a missile without a guidance system to hit its target.

Yet scientism adherents not only wish to eliminate that guidance system, but also claim that the missile’s thrusters and warhead can be what they cannot be: their own guidance system. As scientist Austin L. Hughes explained in 2012 in “The Folly of Scientism: Why scientists shouldn’t trespass on philosophy’s domain”:

Central to scientism is the grabbing of nearly the entire territory of what were once considered questions that properly belong to philosophy. Scientism takes science to be not only better than philosophy at answering such questions, but the only means of answering them.

…Advocates of scientism today claim the sole mantle of rationality, frequently equating science with reason itself. Yet it seems the very antithesis of reason to insist that science can do what it cannot, or even that it has done what it demonstrably has not. As a scientist, I would never deny that scientific discoveries can have important implications for metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics, and that everyone interested in these topics needs to be scientifically literate. But the claim that science and science alone can answer longstanding questions in these fields gives rise to countless problems.

In reality, Hughes understates the case. Scientism adherents may claim they confine “investigation to those sorts of things that are permitted by materialism,” but most are lying — usually to themselves. As soon as they issue statements about right and wrong, they’ve transgressed again their standard. For “science” can’t tell us what we should do, only what we can.

Why don’t we, and shouldn’t we, clone humans or experiment on twins à la Nazi death camp doctor Josef Mengele? It’s not science telling us those things are wrong because science can’t tell us anything is right or wrong.

Under a truly materialist worldview, morality does not compute. You can’t see a principle in a Petri dish or a moral under a microscope. Scientifically speaking, murder is not wrong — only possible.

Oh, people can argue the point, and then we’ll go on that metaphysical merry-go-round. “Murder is wrong because it harms others,” they’ll say. But prove, scientifically, that it’s wrong to harm others. “But murder also hurts society,” they may then state. Okay, prove, scientifically, that it’s wrong to hurt society. Why, the misanthropic zero-population-growth types may say that man is pox upon the planet and, therefore, it would be good to eliminate him. (Of course, they can’t prove their assertion scientifically, either.)

Although popular culture references may always seem a bit frivolous, coming to mind here is perhaps the most realistic scene in the film Terminator 2: Judgment Day. When the young John Connor tells the terminator robot assigned to protect him, “You just can’t go around killing people!” the machine’s response is “Why?” “What do you mean ‘Why?’?” the boy then exclaims, “‘Cause you can’t!”

The terminator again asks why, and all the kid can finally say is, “Trust me on this.” But the robot’s response was entirely rational for an entity programmed to only recognize and consider the material world. Call him that rarest of things: an intellectually honest atheist.

He was also perfectly scientific. And this is why “science,” per se, can’t govern itself. For that which is capable only of pushing back technological limits cannot determine moral limits; something limited to the physical can’t tackle the metaphysical. You can only answer the terminator’s question, logically, by accepting certain basic axioms:

- God exists.

- He has deemed that there is moral law, Truth, that provides universal and unchanging answers to moral questions.

In reality, scientism adherents would reduce us to robots. As the aforementioned Psychology Today article puts it, the belief’s materialism “holds that human beings are just biological machines….”

This is entirely logical if you accept the materialist premise. It’s also an idea that, leading to amorality, would ensure that more of the “biological machines” would themselves become terminators — and the terminated.

spacer

The popular slogan today is “Believe in science.” (Actually, I think the phrase they use is “TRUST THE SCIENCE” Either phrasing implies that science is a religion.) It’s often used as a weapon against people who reject not science in principle but rather one or another prominent scientific proposition, whether it be about the COVID-19 vaccine, climate change, nutrition (low-fat versus low-carb eating), to mention a few. My purpose here is not to defend or deny any particular scientific position but to question the model of science that the loudest self-declared believers in science seem to work from. Their model makes science seem almost identical to what they mean by, and attack as, religion. If that’s the case, we ought not to listen to them when they lecture the rest of us about heeding science.

The clearest problem with the admonition to “believe in science” is that it is of no help whatsoever when well-credentialed scientists–that is, bona fide experts–are found on both (or all) sides of a given empirical question. Dominant parts of the intelligentsia may prefer we not know this, but dissenting experts exist on many scientific questions that some blithely pronounce as “settled” by a “consensus,” that is, beyond debate. This is true regarding the precise nature and likely consequences of climate change and aspects of the coronavirus and its vaccine. Without real evidence, credentialed mavericks are often maligned as having been corrupted by industry, with the tacit faith that scientists who voice the established position are pure and incorruptible. It’s as though the quest for government money could not in itself bias scientific research. Moreover, no one, not even scientists, are immune from group-think and confirmation bias.

So the “believe the science” chorus gives the credentialed mavericks no notice unless it’s to defame them. Apparently, under the believers’ model of science, truth comes down from a secular Mount Sinai (Mount Science?) thanks to a set of anointed scientists, and those declarations are not to be questioned. The dissenters can be ignored because they are outside the elect. How did the elect achieve its exalted station? Often, but not always, it was through the political process: for example, appointment to a government agency or the awarding of prestigious grants. It may be that a scientist simply has won the adoration of the progressive intelligentsia because his or her views align easily with a particular policy agenda.

But that’s not science; it’s religion, or at least it’s the stereotype of religion that the “science believers” oppose in the name of enlightenment. What it yields is dogma and, in effect, accusations of heresy.

In real science no elect and no Mount Science exists. Real science is a rough-and-tumble process of hypothesizing, public testing, attempted replication, theory formation, dissent and rebuttal, refutation (perhaps), revision (perhaps), and confirmation (perhaps). It’s an unending process, as it obviously must be. Who knows what’s around the next corner? No empirical question can be declared settled by consensus once and for all, even if with time a theory has withstood enough competent challenges to warrant a high degree of confidence. (In a world of scarce resources, including time, not all questions can be pursued, so choices must be made.) The institutional power to declare matters settled by consensus opens the door to all kinds of mischief that violate the spirit of science and potentially harm the public financially and otherwise.

The weird thing is that “believers in science” sometimes show that they understand science correctly. Some celebrity atheists, for example, use a correct model of science when they insist to religious people that we can never achieve “absolute truth,” by which they mean infallibility is beyond reach. But they soon forget this principle when it comes to their pet scientific propositions. Then suddenly they sound like the people they were attacking in the previous hour.

Another problem with the dogmatic “believers in science” is that they assume that proper government policy, which is a normative matter, flows seamlessly from “the science,” which is a positive matter. If one knows the science, then one knows what everyone ought to do–or so the scientific dogmatists think. It’s as though scientists were uniquely qualified by virtue of their expertise to prescribe the best public-policy response.

But that is utterly false. Public policy is about moral judgment, trade-offs, and the justifiable use of coercion. Natural scientists are neither uniquely knowledgeable about those matters nor uniquely capable of making the right decisions for everyone. When medical scientists advised a lockdown of economic activity because of the pandemic, they were not speaking as scientists but as moralists (in scientists’ clothing). What are their special qualifications for that role? How could those scientists possibly have taken into account all of the serious consequences of a lockdown–psychological, domestic, social, economic, etc.–for the diverse individual human beings who would be subject to the policy? What qualifies natural scientists to decide that people who need screening for cancer or heart disease must wait indefinitely while people with an officially designated disease need not? (Politicians issue the formal prohibitions, but their scientific advisers provide apparent credibility.)

Here’s the relevant distinction: while we ought to favor science, we ought to reject scientism, the mistaken belief that the only questions worth asking are those amenable to the methods of the natural sciences and therefore all questions must either be recast appropriately or dismissed as gibberish. F. A. Hayek, in The Counter-Revolution of Science, defined scientism as the “slavish imitation of the method and language of Science.”

I like how the philosopher Gilbert Ryle put it in The Concept of Mind: “Physicists may one day have found the answers to all physical questions, but not all questions are physical questions. The laws they have found and will find may, in one sense of the metaphorical verb, govern everything that happens, but they do not ordain everything that happens. Indeed they do not ordain anything that happens. Laws of nature are not fiats.”

“How should we live?” is not one of those questions which natural scientists are specially qualified to answer, but it is certainly worth asking. Likewise, “What risks should you or I take or avoid?” There is a world of difference between a medical expert’s saying, “Vaccine X is generally safe and effective” and “Vaccination should be mandatory.” (One of the great critics of scientism was Thomas Szasz, M.D., who devoted his life to battling the medical profession’s, and especially psychiatry’s, crusade to recast moral issues as medical issues and thereby control people in the name of disinterested science.)

Most people are unqualified to judge most scientific conclusions, but they are qualified to live their lives reasonably. I’m highly confident the earth is a sphere and that a water molecule is two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen. But I do not know how to confirm those propositions. So we all need to rely on scientific and medical authorities–not in the sense of power but in the sense of expertise and reputation. (Even authorities in one area rely on authorities in others.)

But we must also remember that those authorities’ empirical claims are defeasible; that is, they are in principle open to rebuttal and perhaps refutation, that is, the scientific process. Aside from the indispensable and self-validating axioms of logic, all claims are open in this sense. That process is what gets us to the truth. As John Stuart Mill pointed out in On Liberty, even a dissenter who holds a demonstrably wrong view on a question might know something important on that very question that has been overlooked. To our peril do we shut people up or shout them down as heretics. That’s dogma, not science.

TGIF–The Goal Is Freedom–runs on Fridays.

To Watch This Video On BitChute Click The Title Link Below:

To Watch This Video On BitChute Click The Title Link Below:Dave Rubin of The Rubin Report talks to Sohrab Ahmari, the author of “The Unbroken Thread” about how public health authorities used scientism instead of science to push through their preferred policies, how logic and reason led him from atheism to evidence for God, and how the decline of religion has led to the rise of the secular religion of social justice. In this clip Sohrab explains the difference between religion and spirituality and the importance of having rituals be communal. He shares the story of Edith and Victor Turner who studied anthropology and focused on tribal rituals. Upon returning from their research they became Catholics after gaining a new appreciation for the importance of religious rituals and traditions. Sohrab warns that if God is not in the public square, new gods and perhaps a new religion will take its place. He discusses how social justice has gone through this transition by becoming a sort of progressive religion.

Looking for smart and honest conversations about current events, political news and the culture war? Want to increase your critical thinking by listening to different perspectives on a variety of topics? If so, then you’re in the right place because on The Rubin Report Dave Rubin e..

1 year, 4 months ago

spacer

To Watch This Video On BitChute Click The Title Link Below:

To Watch This Video On BitChute Click The Title Link Below:sharing video clips fake news media don’t showcopyright owned by CrowderBits

Why does the “colosseum” look EXACTLY LIKE THE TOWER OF BABEL???? Why did Hollywood make movies to sell us on it yet it’s obvious it’s not a stadium… Why is it half destroyed??? Have you seen pics of what they say the tower looked like??? Ever seen ants in Australia make towers??? What would you do if you had an ant farm and they tried to build a land bridge out?????

Why did the Giza pyramids have to be blown and tunnel into??? Why does it seem more like a chamber for occult druish blood ritual??? Why do they say it’s a tomb and yet we only even have entrance to one pyramid??? Why no chambers in any other pyramid??? Anywhere???

Why do the Stonehenge stones seem like an occult druish ritual circle??? How many pillars in that circle??? 13???

Why do they tell us these evil occult ritual sites are holy but in a good history kind of way???

Pfizer Was Fully Aware That Their ‘Vaccines’ Were Unsafe Robert Kennedy Jr: “Your chance of dying of a heart attack from that vaccine, according to their own studies, is 500% greater than if you’re unvaccinated, so they knew they were gonna kill a lot of people, and they did it anyway.”

8 hours ago

Y. HARARI AT WEF

Y. HARARI AT WEF