style=”font-size: 12pt;”>Oh, how the elite hate truthers!! Especially when we get in the way of their agendas. The stakeholds/elites/ruling class have always, throughout history striven to control the masses. Most often their method of choice ends up being FOOD and WATER. Without these two things humans cannot survive. Not only that, when you destroy the nutrients of the food, you greatly weaken the growth, development and health of the eaters. You know… “the worthless eaters” as you and I are labeled.

The fact checkers and the mainstream media continually deny the truth and declare anyone who contradicts them as CONSPIRACY THEORISTS, or RELGIOUS FANATICS. No one wants to be labelled and shunned. So the masses continue to “believe” the lies they are fed.

This post will be delving deeper into the BUG issue. Though they declare it outloud “YOU WILL EAT THE BUGS”, the masses don’t take it seriously.

The stakeholders have been feverishly working behind the scenes to not only make this a reality, but to make you accept and even embrace it. You are thinking you will save the planet by eating bugs.

They have been acquiring all the farmlands, building their bug farming infrastructure and their edible bug processing plants.

AI Overview / Learn more…Opens in new tab

In the early 1990s, some types of insects that were eaten by people included:

- Survival: Military survival manuals recommend eating insects when other food sources are unavailable.

- Protein: Insects are a time- and energy-efficient way to gather protein.

- Delicacy: Some Indigenous groups ate insects as a delicacy, even when they had other options for hunting or harvesting.

The average American eats about two pounds of dead insects and insect parts each year, which can be found in vegetables, rice, beer, pasta, spinach, and broccoli.

AI Overview / Learn more…Opens in new tab

Insect farming facilities are warehouses that raise insects like mealworms, crickets, and fly larvae for protein, oil, and fertilizer. Some of the companies that operate insect farms include:

Last week, a warehouse in Youngstown, Ohio became the first edible bug farm in the United States. Called “Big Cricket Farms,” it produces what’s being called “bug flour,” made from milled crickets, to produce a snack chip marketed as “Chirps”.”

Now, there are already bug farms operating in Texas that produce insects for pet food, but food for people is held to a higher standard, thankfully, especially when it comes to what the insects are being

Why Don’t More Humans Eat Bugs? excerpts only

Perhaps the agricultural revolution catalyzed the departure of bugs from the Western diet. Hunter-gatherers, she reasoned, might have snacked on wild ants and beetles, but insects would have become pests once people started farming.

This hypothesis quickly crumbled. Many insectivorous countries today are also agricultural. And when Lesnik tested the idea more rigorously—by determining country by country if the percent of arable land correlates with bug-eating habits—she found no correlation.

It could be that people eat bugs more often in poor countries or as a fallback food when there isn’t enough to eat. Lesnik looked at a map showing the number of insect species consumed in each country to see if bug-eating habits correlate with gross domestic product. They don’t. Nor does insect consumption relate to population density, which you might expect if societies turn to bugs when there are too many mouths to feed.

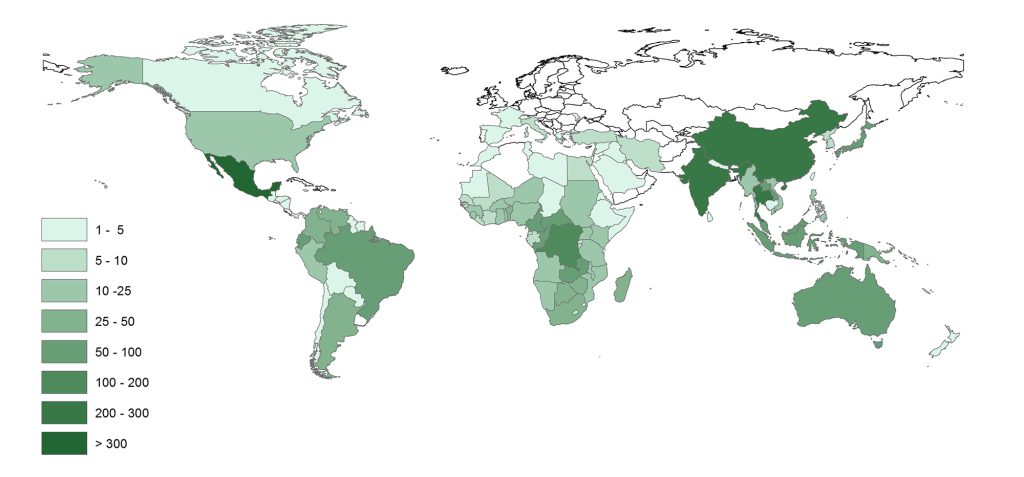

In the end, it mostly comes down to geography, an idea previously suggested by the anthropologist Marvin Harris in the 1990s. “Latitude—where you are in the world—seems to be the number one predictor of who’s going to be eating insects,” Lesnik says. People in China and Mexico are among those who eat the most bugs—more than 300 species—whereas no edible insect species were found in Russia and Scandinavian countries near the Arctic Circle. Lesnik published these findings last year in the American Journal of Human Biology.

The results resonate with Arnold van Huis, an entomologist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands who wrote about insects as food for a 2017 book on human-animal interactions. Insects flourish in warmer areas. In the tropics, he explains, bugs are larger—and more meal worthy—than in temperate zones where many lay dormant or die in winter.

The latitude theory also jibes with human history and migration patterns. Neanderthals, humans’ closest extinct relatives, roamed what’s now Europe and Central Asia during a harsh, wintry era when ice blanketed much of their habitat.

Living in the tundra with no easy calories from fruits or vegetables, they relied on hunting deer and other creatures that ate woody plants. “The only way to survive up there was to eat animals,” Lesnik says. “And you don’t need alternative insect protein when you’re already eating meat all year round.” The Neanderthal diet may help explain food choices in the West. “If we’re tracing our history … edible insects would have been important to hominids anywhere else in the world except in those really cold environments,” Lesnik says.

Still, even if geography and climate explain how bugs faded from the Western diet, they don’t explain the deep-rooted disgust so many people feel when facing an insect or arthropod-laced meal—their knee-jerk “Ewww!”

Based on her findings about geography, Lesnik turned to history, zooming in on the Age of Exploration, beginning in the 15th century, when Europeans were crossing latitudes and exploring insect-rich equatorial regions. Here she hit a new factor: the clash of cultures.

Consider, for example, the remarks of Diego Álvarez Chanca, the fleet physician of Christopher Columbus’ 1493 Caribbean expedition. He wrote that locals “eat all the snakes, lizards, spiders, and worms that they find upon the ground so that, according to my judgment, their bestiality is greater than that of any other beast on the face of the earth.”

This attitude reflects what anthropologists call “ethnocentric bias”—the tendency to evaluate other cultures according to preconceptions based on the customs of one’s own culture. Often this sort of bias results in “othering,” seeing our own life practices as normal and regarding others’ habits as alien and substandard.

“As anthropologists, we’re trained to be very aware of this [bias] and to avoid it,” Lesnik says. “If we’re going to try to understand people from all around the world, we need to understand them from their perspective, from their values.” Well, that is necessary for a GLOBAL GOVERNMENT. EVERYONE MUST JOIN AT THE LOWEST COMMON DENOMINATOR!!

But European explorers had no such training, and their attitude of superiority over the Indigenous peoples they met or observed extended to people’s choice of food. On a Caribbean voyage in 1527, one Spanish traveler described the Native people’s diet as driven by desperation: “Now and then they kill deer and at times get a fish, but this is so little and their hunger so great that they eat spiders and ant eggs, worms, lizards, and salamanders and serpents.”

The why part I’ve got. Bugs carry diseases humans can get. RE: Mosquito and Malaria. And bug is a common description referring to things humans can only see with Microscopes.

Here’s a current definition from the “Medical Dictionary” [a. A disease-producing microorganism or agent: a flu bug. b. The illness or disease so produced: took several days to get over the bug.]

Have to get back to you if I can find out when that relationship, bug and illness, happened.

Okay, a bit more. The first published account of bugs and illness was written by Pliny the Elder around 77 A.D. In Pliny’s “Natural Journal” he writes about Bed Bugs and relates illness directly to the bugs. That connection was likely known in populations for years before it was written about. (note – a book back then, 77 A.D., would be hand written, rare, and very expensive) There is a lot of history relating actual bugs to various plagues and war casualties. During the Napoleonic War years France lost 4 times as many men to insect related illness as they did in actual battles. Bug, as an insect, causing, and curing illnesses became more widespread in books during the 1600’s.

Numerous sources relate the word bug as a Welsh word from ‘bwg’ dating back to the Middle English period around 1200 – 1500, but that Welsh ‘bug’ was aligned with evil spirits and the devil centuries earlier than its useage referring to insects and bug borne diseases in texts starting in the 1600’s. Which practice has carried on through to the 21st Century. Bug as a standalone illness reference I’ve yet to discover.

Offshoots of BUG : aka’s – a lobster 🦞, a software or electronic glitch (there’s an actual Moth in a Museum that caused the first computer problem), a lighthouse (1884 in “The Nation” answering a why lighthouse was a bug question reasoned the flashing light in a lighthouse was like a ‘firebug’ or ‘lightning-bug’ – where a lighthouse is/was called a bug I don’t know), an irritating person can bug you

spacer

Eva Vlaardingerbroek: Push for insect eating is a ‘compliance test’

LINK: https://www.foxnews.com/video/6325081895112 ![]()

spacer

Entomophagy is a new phenomenon in the West, and as a result it is rarely regulated. This leads to public institutions like food agencies, customs and health departments often finding themselves helpless in the face of new product development based on processed insects.

|

|

ENTOMOPHAGY: What it’s all aboutYou’ve never heard this word? You think it sounds funny to you? Well, entomophagy is nothing new in fact. It’s something practiced since the dawn of time: eating bugs. If that term can be used to speak of human beings, it is much more common to refer to the diet of so-called entomophages animals, especially insects that eat other insects. Where does it come from?Eating bugs is not so strange as you might thinj. In ancient Greece, they already had two words fot that, “entomos” (incised, notched) and entoma which simply means “insect”. Add to it the prefix phàgos, meaning “eater”, and you get “entomophagy”. Which translate as “eater of bugs“. If you look closely at its roots, eating bugs should only mean the consumption of insects but as an extension, it also includes scorpions, spiders and millipedes which are not insects but arthropods. |

|

Yes, the ancient Greeks ate insects, including cicadas, locusts, and grasshoppers:

The practice of eating insects is called entomophagy, which comes from the Greek words éntomon meaning “insect” and phagein meaning “to eat”

The ancient Romans are known to have eaten various insects, including beetles, caterpillars, and locusts. Insects such as crickets, grasshoppers, and ants have been eaten for centuries and are still considered a delicacy in many parts of the world, especially in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Oceania. |

spacer

From a geographical point of view, there are three legal trends. First, there are the “Anglo-Saxon” countries: UK, USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia, for whom edible insects do not represent a novel food, and the food agencies have authorized import and sales.

Then there are the non-English-speaking Western countries, and the European Union, in particular, which have felt the need to have rules and provide approvals before allowing any marketing.

Non-Western countries comprise the remaining trend: there, insects are often a traditional food, but rarely packaged and exported or imported.

In these countries, customs and the FDA had never found themselves facing packaged products containing insects, as insects were usually found in the local market, unpackaged. And in the absence of regulations these agencies have sometimes shown inconsistent reactions.

I’ve compiled here a collection of the regulatory position of insects in some countries. Matters that may be subject to rules are breeding, production, marketing, and import/export. There are cases where the marketing of edible insects is legal, but the import or export is not (for example, Belgium does not accept insects from non-EU countries).

In addition, there is the matter of food legislation, which is often lacking industry standards for insect foods. In particular, insects are not included in the Codex Alimentarius, which contains an international guideline for food safety.

Additions to the Codex will be decided by member nations of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations at their next quadrennial meeting.

Customs offices also often have difficulty in finding reference points. Harmonised system codes decided internationally by the World Customs Organisation for the nomenclature of goods do not contain any definition that refers to insects as food. The creation of new codes can be requested by a member state, but the process will take probably years.

Canada

Crickets are not considered as a novel food, and today the largest breeder in North America is located in Canada and serves some local start-ups, including One Hop Kitchen. If, however, an insect lacks a history of safe consumption, it might fall back into the novel food category pending an evaluation by the Bureau of Microbial Hazards in the Food Directorate.

USA

There is no specific set of standards for edible insects in USA. The FDA has made public its opinion, which is the current legal basis for the market. To be allowed for market, the insects must have been bred for human consumption. Products containing insects must of course follow the standards required by the FDA including bacteriological tests and good manufacturing practice certification. The label on the product must include the common name and the insect’s scientific name, and note the potential risks of allergy. Import from other countries is allowed, and the US FDA has already updated its Import Prior Notice with a list of edible insects products.

Australia and New Zealand

Both nations share an agency for the maintenance of food safety, Fsanz. This agency has addressed some cases like the super mealworm (Zophobas morio ), the domestic cricket (Acheta domesticus ) and the moth (Tenebrio molitor ), deciding that they are not novel foods, even though they cannot be considered traditional foods either. In particular, they have yet to encounter food safety problems and consequently have not been put to the consumption limits or import.

European Union

In 2015, the European Parliament decided that insects fall into the “novel foods” category, and consequently are subject to lengthy approval processes. From January 2018, the new Novel Food law is in place, and the application is supposed to be simplified.

The list of application submitted to the European Commission Food, Farming and Fisheries is here. Species included as of December 2018 are:

| Insect | Applicant | Proprietary content requested |

| Whole and ground Alphitobius diaperinus (lesser mealworm) larvae products* | Proti-Farm Holding NV | Yes |

| Dried Gryllodes sigillatus (banded crickets) |

Micronutris | Yes |

| Whole and ground Acheta domesticus (house cricket) | Belgian Insect Industry Federation | No |

| Locusta migratoria (migratory locust) |

Belgian Insect Industry Federation | No |

| Dried Tenebrio molitor (mealworms) |

Micronutris | Yes |

The European Commission (EC) has developed an e-submission system for Novel Food applications. At this webpage you can find the link to the e-submission systems and to the PDF with the explanations.

The timeframe in an hypothetical “ standard” case (where no additional information is requested) should be as follow:

– 1 month (European Commission, for a formal check)

– 30 working days (at the Food Authority, if a technical preliminary verification is needed)

– 9 months (at the Food Authority, for validation of all the data)

– 7 months (at the European Commission, for the draft implementing act)

TOTAL: 1 year and a half. This timeframe is hypothetical. The new Novel Food law is in place since January 2018, as of December 2018 no insect applications has made it to the final phase, so there are no precedents to refer to in terms of timeline. Once a species is approved, all the products containing it can be marketed in all the EU country. In other words, once the food (for example, the house cricket) is approved, it is for everyone’s benefit, including the producers and importers.

In some countries there is a certain degree of tolerance (France, for example). In others, such as Italy, the tolerance is close to zero. Germany has become very tolerant in 2018 and some bug products are in supermarkets since then.

5 countries did not accept the 2015 decision of the EU and since then has permitted – and in some case, regulate – the marketing and consumption of insects. These are Belgium, Britain, the Netherlands, Denmark and Finland, and their position is described below.

Belgium

The Federal Agency for the Safety of the Food Chain has produced a specific regulation for edible insects which made Belgium one of the most advanced nations in terms of entomophagy, although no insects bred outside of the European Union are accepted. They updated their regulation in 2018 according to the EU transitional period and they are expected to stick to the EU rules from 2019 (http://www.afsca.be/foodstuffs/insects/)

Netherlands

The Netherlands is home to some mealworm and cricket farms designed to breed for for human consumption. These include the leader, Protifarm (and its subsidiary Kreca), as well as some start-ups active in the marketing and production of edible insects. Its legal basis is not clear, though, and the public body responsible for food safety (NVWA) has refused to comment.

Denmark

The Danish Veterinary and Food Administration believes that whole insects (including flour, if coming from whole insects) do not fall under the EU novel food legislation. As a result, imports from non-EU countries is possible for those insects falling under the transitional period (mealworm and house crickets, for example). Denmark is jumping ahead with edible insect intitiatives.

Finland

Finland has followed the danish example in 2017, releasing rules for import and sales of edible insects. As for the other countries which allowed edible insect prior to 2018, in 2018 they are in the transitional period. It is not clear what will happen in 2019.

Germany

The control of food in Germany is a task for the 16 federal states. The Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety (BVL) fulfils only some coordination functions, so its position is not legally binding and it is aligned with the EU commission decision: insects or parts of insects are novel food and cannot be sold in Germany until a procedure for novel food approval has been finalised. But in March 2018 Metro Group announced the launch of a mealworm pasta, therefore we must assume they got a local or federal green light for it.

Norway

Norway is not an EU member, but belongs to the European Economic Area and therefore follows a number of European regulations. Still, their interpretation of edible insects is that when they are whole (as opposed to parts or isolates of insects), they do not fall under the novel food law. Import would be accepted if custom is cleared in an EU country. This is the position of the Norwegian food agency.

Britain

For years, the Food Safety Agency has shown a favourable position on the sale, consumption and import of edible insects. The future is uncertain, because of Brexit, but most likely insects will be allowed to keep on being sold on the market.

Switzerland

In December 2016, the council passed an edible insect law (which took take effect May 1, 2017) allowing the sale and consumption of three species: crickets (Acheta domesticus), migratory locust and mealworm. Among the requirements, the insects must have been bred for human consumption and after slaughter must be treated according to the criteria of food security (high temperatures, freezing, etc.). The rules released by the food agency (OSAV) are very strict and complex. In the case of import from non EU countries, they requires the insect to be whole, shipped only by plane to Zurich or Geneva, and accompanied by an incredibly long list of lab test and certificates.

Non-western countries

Southeast Asian countries have a tradition of entomophagy, but do not have regulations relating to the breeding, sale and export of insects. Thailand, the world’s largest breeder of crickets, has released the guidelines for cricket farming (GAP – Good Agricultural Practice) in 2017. An English version of the Thai GAP standard is available here.

Even in China, insects are a common culinary ingredient in many regions, but there are still no mentions of this in food law. An exception, though, is silkworm pupae, which was included in 2014 in the list of foods allowed by the Ministry of Health. China is the world’s largest producer of silk (500.000 tons of silkworm pupae per year).

South Korea’s government launched a process to legalise some edible insects in 2011. On the list there are mealworm, crickets (not the usual Acheta Domesticus , but the Gryllus bimaculatus species) and some larvae. Following this preliminary process, in 2016, the Korean Food and Drug Administration classified crickets and mealworms as normal foods, without restrictions. It is expected that other insects will be added soon to the eligibility list.

spacer

Edible insects (wikipedia)

Frequently consumed insect species

Human consumption of 2096 different insect species has been documented.[3]

The table below ranks insect order by number and percentage of confirmed species consumed and presents each insect orders’ percentage of known insect species diversity.[3][15][16] With the exceptions of orders Orthoptera and Diptera, there is close alignment between species diversity and consumption, suggesting that humans tend to eat those insects that are most available.[17]

| Insect order | Common name | Number of confirmed species consumed by humans[3] | Percentage of insect species consumed by humans (%)[3] | Percentage of total insect species (%)[15] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coleoptera | Beetles | 696 | 33 | 38 |

| Lepidoptera | Butterflies, moths | 362 | 17 | 16 |

| Hymenoptera | Bees, wasps, ants | 321 | 15 | 12 |

| Orthoptera | Grasshoppers, locusts, crickets | 278 | 13 | 2 |

| Hemiptera | Cicadas, leafhoppers, planthoppers, scale insects, true bugs | 237 | 11 | 10 |

| Odonata | Dragonflies | 61 | 3 | 1 |

| Blattodea | Termites, cockroaches | 59 | 3 | 1 |

| Diptera | Flies | 37 | 2 | 15 |

| Others | – | 45 | 2 | 6 |

Geography of insect consumption

[edit]

Insect species consumption varies by region due to differences in environment, ecosystems, and climate.[18][19] The number of insect species consumed by country is highest in equatorial and sub-tropical regions, a reflection of greater insect abundance and biodiversity observed at lower latitudes and their year-round availability.[19][17][20]

For a list of edible insects consumed locally see: List of edible insects by country.

Edible insects for industrialized mass production

To increase consumer interest in Western markets such as Europe and North America, insects have been processed into a non‐recognizable form, such as powders or flour.[21] Policymakers, academics,[4] as well as large-scale insect food producers such as Entomofarms in Canada, Aspire Food Group in the United States,[22] Protifarm and Protix in the Netherlands, and Bühler Group in Switzerland, focus on seven insect species suitable for human consumption as well as industrialized mass production:[5] SUITABLE ACCORDING TO WHO?? BASED ON WHAT?? WHO APPOINTED THEM TO MAKE THOSE DETERMINATIONS?

- Mealworms (Tenebrio molitor) as larvae

- Lesser mealworms (Alphitobius diaperinus) as larvae, mostly marketed under the term buffalo worms.

Pancakes made from insect powder, served with strawberries and skyr - House cricket (Acheta domesticus)

- Tropical house cricket (Gryllodes sigillatus)

- European migratory locust (Locusta migratoria)

- Black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens)

- Housefly (Musca domestica)

Cochineal (Dactylopius coccus) is collected to produce carmine, a red dye used for textiles and food. It was largely substituted with synthetic dies like alizarin. Fears over the safety of artificial food additives renewed the popularity of cochineal dyes, and the increased demand has made cultivation of the insect profitable again,[23] with Peru being the largest producer, followed by Mexico, Chile, Argentina and the Canary Islands. Isn’t that clever, they got the westerners to go back to buying the bugs to make red food coloring because that helped meet the UN Goals to move western money to the “underdeveloped nations

-

Freeze-dried mealworms as food (or food ingredient)

-

Buffalo worms as food (or ingredient)

-

House crickets as food (or ingredient)

-

Migratory locusts as food (or ingredient)

Insect food products

The following processed foods are produced in North America (including Canada), and the EU:

- Insect flour: Pulverized, freeze-dried insects (e.g., cricket flour).

- Insect burger: Hamburger patties made from insect powder / insect flour (mainly from mealworms or from house cricket) and other ingredients.[42]

- Insect fitness bars: Protein bars containing insect powder (mostly house crickets).

- Insect pasta: Pasta made of wheat flour, fortified with insect flour (house crickets or mealworms).

- Insect bread (Finnish Sirkkaleipä): Bread baked with insect flour (mostly house crickets).[43]

- Insect snacks: Crisps, flips or small snacks (bites) made with insect powder and other ingredients.[44]

Food and drink companies such as the Australian brewery Bentspoke Brewing Co and the South African startup Gourmet Grubb have introduced insect-based beer,[45] a milk alternative, and insect ice cream.[46]

Are you paying attention? Have you not noticed in the past few decades that our food has changed? Bread, milk, cheese, pancakes, cake flour, noodles, meat, crackers, cookies… no longer look, taste, smell or behave the same as the did before. They have been switching us over to bug products for years already without our knowledge or consent.

Were you even aware that they have also been genetically modifying our vegetables and GASSING them for decades now?

All of these things change our DNA. You know the old saying “YOU ARE WHAT YOU EAT”! That is no joke folks.

Our bodies were designed to digest and assimilate the food that grew naturally on the earth, processing the energy from the sun, the nutrients from the soil and the water from the rain to build strong bodies. This garbage that they create artificially, and these farms where they grow bugs that are fed God knows what and not even exposed to water, soil or sunshine, along with the vegetables that are genetically altered and grown in factories hydroponically, meaning without the benefit of soil… are not giving your body anything that it needs to grow and prosper.

Food safety

Like other foods, the consumption of insects presents health risks stemming from biological, toxicological, and allergenic hazards.[47][48] Biological hazards include bacteria, viruses, protozoa, fungi and mycotoxins; toxological risks are poisons, pesticides, heavy metals and antinutrients; allergenic hazards relate to arginine kinase, tropomyosin and α-Amylase.[49]

In general, insects harvested from the wild pose a greater risk than farmed insects, and insects consumed raw pose a greater risk than insects that are cooked before consumption.[47] Feed substrate and growing conditions are the main factors influencing the microbiological and chemical hazards of farmed insects.[50][51]

The table below combined the data from two studies[52][53] published in Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety and summarized the potential hazards of the top five insect species consumed by humans.

| Insect order | Common name | Hazard category | Potential hazard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coleoptera | Beetle | Chemical | Hormones |

| Cyanogenic substances | |||

| Heavy metal contamination | |||

| Lepidoptera | Silkworm | Allergic | |

| Chemical | Thiaminase | ||

| Honeycomb moth | Microbial | High bacterial count | |

| Chemical | Cyanogenic substances | ||

| Hymenoptera | Ant | Chemical | Antinutritional factors (tannin, phytate) |

| Orthoptera | House cricket | Microbial | High bacterial count |

| Hemiptera | Parasitical | Chagas disease | |

| Diptera | Black soldier fly | Parasitical | Myiasis |

The hazards identified in the above table can be controlled in various ways. Allergens can be labelled on the package to avoid consumption by allergy-susceptible consumers. Selective farming can be used to minimize chemical hazards, whereas microbial and parasitical hazards can be controlled by cooking processes.[53]

Oh sure, we trust the FOOD INDUSTRY to take all the necessary precautions and protect us… I mean it is not like we have seen all kinds of food related illnesses and deaths already, along with numerous recalls due to the failure of the systems already in place. Now, we are going to take all these known carriers of disease and filth and trust the Food Industry to turn them into nourishment for our bodies. LOL LOL LOL!!!

When God’s creation was allowed to function the way that HE designed it, ANYONE could find FOOD wherever they were. And it was clean and edible as it was found. When we started using science and technology and trusting the INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX with our lives… everything went to HELL. And yet, we continue to TRUST THEM!! INSANITY.

As a further guarantee for consumers, quality labeling has been introduced by the Entotrust programme, an independent and voluntary product certification of insect-based foods, which allows producers to communicate the safety and sustainability of their activities.[54]

LOL LOL LOL… so that is their guarantee…? Labeling. We have all seen the farce that is labeling. It is just a word game. They manipulate the truth for their benefit. It boggles the mind what they can call “100% Natural” or “Organic” or “PURE”. Not to mention all the other creative terminology used on labels to cover up the truth.

spacer

Hurdles to the use of insects as food and feed Source

Although a myriad of opportunities exists for entomophagy, there are significant hurdles to overcome as a result of the lack of research and the need for innovation within the sector. Major issues include the possibility that insects may contain ‘anti-nutrient’ properties, concerns around food safety related to storage and allergic reactions, consumer acceptability and ambiguous or non-existent regulation.

Anti-nutrient properties

Chitin is a structural nitrogen-based carbohydrate found in the exoskeleton of insects, which may have ‘anti-nutrient’ properties due to potential negative effects on protein digestibility (Belluco 2013). One study of seven insect species found 2.7–49.8 mg chitin per kg fresh weight and 11.6–137.2 mg/kg in dry matter (Finke 2007). A study comparing dried honey bees and honey bee protein concluded that the removal of chitin improved the quality of the insect protein as measured through protein digestibility, amino acid content, protein efficiency ratio and net protein utilisation (Ozimek et al. 1985). On the other hand, chitin is notably high in fibre, and chitin extracts from the exoskeletons of shellfish have been approved by relevant authorities and are readily used in Japan as a source of fibre in cereals (DeFoliart 1992). Although chitin is usually considered to be indigestible by humans (Bukkens 1997), chitinolytic enzymes, produced by bacteria from human gastrointestinal tracts, have recently been found, suggesting that chitin and chitosan can be digested (Paoletti et al. 2007; Dušková et al. 2011; Rumpold & Schlüter 2013a).

In a 2-week trial with healthy adult males, chitosan, a derivative of chitin, ingested at a dose of 3–6 g/day, resulted in a significant decrease in total serum cholesterol and an increase in serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol (Koide 1998). It has also been suggested that for poultry, chitin has a positive effect on the immune system and thus may reduce the need for antibiotic use (van Huis 2013). However, the effect of long-term ingestion of chitin is unknown (Koide 1998), and more research is required in this area to understand the impact of chitin on human health and animal health.

The potential toxicity of some compounds in insects is also of concern. There are two categories of toxic insects: cryptotoxics and phanerotoxics. Cryptotoxics contain toxic substances from either direct synthesis or by accumulation from their diet. Phanerotoxics have specific organs that synthesise toxins (Belluco 2013). Commonly consumed insect species are not in either category, and studies of the levels of hydrocyanide, oxalate, phytate, phenol and tannins in edibles insect species have found that values fall well below levels of toxicity for human consumption (Ekop et al. 2010; Shantibala & Lokeshwari 2014). Analysis of the larvae of Cirina forda has confirmed that oxalate and phytic acid levels are well within safe ranges and that they contain no tannins (Omotoso 2006). A further clinical trial that fed Sprague-Dawley rats varying levels of freeze-dried mealworm powder over a 90-day period found no toxic effects (Han 2016). Overall, data on anti-nutrient properties of edible insects are limited, and more research is required.

Microbial risks

Spore-forming bacteria and enterobacteriaceae have been reported in mealworms and crickets, with higher levels found in insects that had been crushed – likely due to the release of bacteria from the gut (Klunder 2012). For the species examined (Gryllotalpa africana, R. phoenicis, Bematistes alcinoe), the main bacteria identified were from the genera Bacillus and Staphylococcus, and the majority of the microbes were saprophytes (Amadi & Kiin-Kabari 2016). Analysis of edible insects for the Belgian market identified that all untreated fresh insect samples had an aerobic mesophilic microorganism, yeast and mould count higher than the Good Manufacturing Practice limits for raw meat (FDA 2017); however, introducing a simple blanching step in the processing reduced levels to below accepted limits (Megido 2017). Further research indicates that treating insects the same as other foodstuffs of animal origin during processing (i.e. washing and thorough heating) sufficiently reduces the risk of bacteria-borne disease (Grabowski & Klein 2016).

While harmful bacteria such as Salmonella have been detected in insects that were in close contact with livestock (Belluco 2013), research suggests that the majority of the contamination comes from the gut microbiota of the insect (Rumpold 2014). Starving insects for 24–48 hours prior to slaughter has been suggested as a way to reduce harmful bacteria in the gut, although the one published study in this area reported that this approach had no significant impact on microbiota levels (Wynants 2017), and unpublished studies also support this finding (Larouche et al. 2017). Some risk of mycotoxins has been identified, but this has been studied only in the two emperor moth species (Imbrasia belina and Bucnaea alcinoe), with strains identified predominantly in the intestinal tract or from outside contamination (Simpanya & Allotey 2000; Braide & Oranusi 2011). These risks may be mitigated with evisceration and appropriate processing steps, as is done with other meat sources.

Studies on the level of organic and metal contaminants (e.g. polychlorinated biphenyl, DDT, dioxin compounds, heavy metals) in both whole edible insects and insect-based food items in Belgium found that all contaminant levels were generally lower than that was found in other common animal products (Poma 2017). This study indicates that consuming insects presents no more of a microbial or contaminant risk than consuming other meat sources, when the same good practice standards of preparation are applied.

Little is known about how to safely store insects to reduce microbial risk. Research has shown that freshly boiled insects spoil rapidly at room temperature (28°C) but remain stable at 3–5°C over a 2-week period; microbial levels in dried insects have also been reported to be stable at room temperature (Klunder 2012).

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) published a risk profile examining hazards relating to insects as food and feed, considering the entire production chain. EFSA came to the overall conclusion that if the currently permitted feed materials are used as the growth substrate for the insects, the possible occurrence of significant microbial hazards is comparable to other sources of protein of animal origin (EFSA 2015). Further systematic work is required to establish the safe shelf-life of edible insects, both for human and animal consumption.

Allergens

Many arthropods, which includes insects, arachnids, myriapods and crustaceans, are known to induce allergic reactions in susceptible individuals, caused by the presence of tropomyosin, arginine kinase, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and haemocyanin (Belluco 2013; Srinroch 2015). Cross-reactive allergies have been identified in crustaceans, cockroaches and dust mites. One study identified a positive cross-reaction between mealworm proteins and individuals with known dust mite and crustacean allergies (Verhoeckx 2013; Van Broekhoven et al. 2016). A study on crickets (G. bimaculatus) showed a cross-reaction to crickets in individuals with known prawn allergies (Srinroch 2015). In this study, an additional novel allergen was identified in the cricket, hexamerin1B (Srinroch 2015). A recent systematic review of studies examining cross-reactivity/sensitivity with insects in individuals with known arthropod allergies has indicated that all patients demonstrated allergic reactions to insects (Ribeiro & Cunha 2017). In addition to direct consumption, there is evidence to support contact allergy sensitivity in individuals frequently exposed to insects; for example breeding farm workers (Jensen-Jarolim & Pali-Schöll 2015).

The data on allergen risk to insects are limited as the majority of trials to date have been conducted with a small number of participants (n < 20); however, these studies point in the direction that individuals with crustacean allergies will react negatively to insects and that there may be several additional novel insect allergens to consider.

Mass production

For insects to be considered a viable microlivestock, it must be possible to produce them on a large scale in a sustainable, safe and efficient way. It is frequently forgotten that large-scale domestic rearing of insects has been occurring for over 7000 years for sericulture (silk), apiculture (honey), biological control of pests and the production of medicinal products and shellac (Rumpold & Schlüter 2013b). Significant advances have been made with artificial rearing diets and controlled conditions for mass rearing. However, there are still several hurdles preventing the scaling up of insect farming for human and animal consumption. First and foremost, an ideal candidate insect species for mass rearing must be identified. Domestication has occurred for several thousand years with silkworms, and it has been documented that domestic silkworms can no longer effectively cling to branches and would die in the wild (Defoliart 1995). Crickets and palm weevils are mass reared in Thailand, but they are not the ideal species as they are reared on high-quality chicken feed. The ideal insect species would have high egg production, high egg hatch, a short larval stage, optimum synchronisation of pupation, high weights of larvae or pupae, a high productivity (i.e. high conversion rate and high potential of biomass increase per day), low feed costs, low vulnerability to diseases, ability to live in high densities and a high-quality protein content (Rumpold & Schlüter 2013b). The search for such an insect continues, although the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) does meet the above criteria, the issue of optimisation of farming techniques remains.

The majority of livestock and agricultural production systems have some level of automation, reducing the expense of manual labour. This is not the case for the majority of insect farms where manual labour is still required to complete tasks such as feeding, collection, cleaning and rehousing (Rumpold & Schlüter 2013b). This dependence on manual labour means that farm-reared insects are expensive, even when feed costs are low. There are a handful of companies that have developed automation, but these are still in trial phases. Thus, in order for insects to be an attractive alternative to protein sources such as beef and poultry, automation must be further developed to bring down the price of the end product.

In addition to the labour costs, the conditions in the rearing facility such as temperature, light, humidity, ventilation, rearing containers, population density, oviposition sites, feed and water availability, feed composition and quality and microbial contaminants must be controlled at the optimum levels for successful mass production (Rumpold & Schlüter 2013b).

spacer

Greed, New Form of Religion, or Compliance Test: Why Are Britons Forced to Eat Bugs?

SubscribeEkaterina Blinova

Where Did the Idea of Eating Insects Originate?

Who’s Driving the Bug Business?

Sputnik

@SputnikInt

Greed, new form of religion, or compliance test: Why are Britons being forced to eat bugs? The UK’s National Alternative Protein Innovation Centre (NAPIC) received £15 million ($19.5 million) in British taxpayer money to make insect-based proteins along with cultured meat “a sustainable and nutritious part” of Britons’ diets. Over the past few years, the UK press has peddled the idea of embracing edible insects as an alternative to meat: “British firms strive to create a buzz around insect farming” “Edible insects and lab-grown meat are on the menu” “Would you eat insects if they were tastier?” “Why it’s time to embrace edible insects” Greed, new form of religion, or compliance test: Why are Britons being forced to eat bugs? The UK’s National Alternative Protein Innovation Centre (NAPIC) received £15 million ($19.5 million) in British taxpayer money to make insect-based proteins along with cultured meat “a sustainable and nutritious part” of Britons’ diets. Over the past few years, the UK press has peddled the idea of embracing edible insects as an alternative to meat: “British firms strive to create a buzz around insect farming” “Edible insects and lab-grown meat are on the menu” “Would you eat insects if they were tastier?” “Why it’s time to embrace edible insects” Where did the idea of eating insects originate? Entomophagy, or eating insects, has been actively promoted at the World Economic Forum (WEF), which insists that the consumption of insects “can offset climate change in many ways” and prevent the “impending food crisis,” as the world’s population is set to reach 9.7 billion people by 2050, with just 4% of arable land remaining available. Who’s driving the bug business? EnviroFlight (US), Innovafeed (France), HEXAFLY (Ireland), Protix (Netherlands), Global Bugs (Thailand), Entomo Farms (Canada), and Ynsect (France) are named as key players in the market. Insect protein firms are attracting hefty investments from global foundations and food giants. In 2012, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation granted $100,000 to All Things Bugs to explore insect food production benefits. Indeed, the New York Post has nailed US globalist billionaires’ attempts to control food and agriculture. According to the newspaper, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg are investing in “alternative protein.” Gates, an advocate of entomophagy, has amassed about 270,000 acres across the US. In 2017, Protix raised $50.5 million in equity and debt funding, marking the largest investment in the industry at the time. ADM and Cargill invested a whopping $250 million in the French insect protein firm Innovafeed in September 2022. In 2023, the US food giant Tyson poured around $58 million into Protix. Where did the idea of eating insects originate? Entomophagy, or eating insects, has been actively promoted at the World Economic Forum (WEF), which insists that the consumption of insects “can offset climate change in many ways” and prevent the “impending food crisis,” as the world’s population is set to reach 9.7 billion people by 2050, with just 4% of arable land remaining available. Who’s driving the bug business? EnviroFlight (US), Innovafeed (France), HEXAFLY (Ireland), Protix (Netherlands), Global Bugs (Thailand), Entomo Farms (Canada), and Ynsect (France) are named as key players in the market. Insect protein firms are attracting hefty investments from global foundations and food giants. In 2012, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation granted $100,000 to All Things Bugs to explore insect food production benefits. Indeed, the New York Post has nailed US globalist billionaires’ attempts to control food and agriculture. According to the newspaper, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg are investing in “alternative protein.” Gates, an advocate of entomophagy, has amassed about 270,000 acres across the US. In 2017, Protix raised $50.5 million in equity and debt funding, marking the largest investment in the industry at the time. ADM and Cargill invested a whopping $250 million in the French insect protein firm Innovafeed in September 2022. In 2023, the US food giant Tyson poured around $58 million into Protix. |

Insects Can Be Toxic, But Entomophagy Proponents Don’t Care

What Does the Western Public Say?

Throughout history, animals, including insects, have often been imbued with spiritual significance and regarded as sacred or symbolic beings. Even nowadays, they are often seen as symbols of the natural world; as such, they represent our connection to the Earth and the cycles of life and death. They can also symbolize the seasons, the elements, and the different forces of nature and have, therefore, been associated with specific qualities and traits, such as strength, wisdom, speed, or cunning [2]. For example, in ancient Egypt, the scarab beetle was associated with the god Khepri and represented rebirth and renewal [3]. In Hinduism, cows are considered sacred and should not be harmed [4].In many ancient cultures, insects were associated with death, decay, and impurity; therefore, they were considered unclean.In ancient Greece, the consumption of insects was not widespread or prominent compared to other food sources. The ancient Greeks primarily relied on a diet that consisted of grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, fish, meat (mainly lamb and pork), and dairy products. Insects were not a significant part of their culinary practices or cultural traditions [30]. However, it is worth noting that some historical sources mention the use of certain insects as food and feed in ancient Greece, albeit to a limited extent. For example, the philosopher and naturalist Aristotle wrote about using Cossus cossus (L.) caterpillars as bait for fishing. He noted that the caterpillars were especially effective at attracting fish and were commonly used by fishermen in his time. In Book V of “The History of Animals” [31], Aristotle described the life cycle and habits of the Cossus caterpillar, which, according to him, was commonly found in the Mediterranean region. He mentioned that Cossus caterpillars were used by the ancient Greeks as a source of food, particularly by those living in rural areas. Aristotle also noted that Cossus caterpillars were considered a delicacy by some people, who would roast or boil them before eating them [32]. He described their flavor as sweet and nutty, with a mushroom-like texture [33].

Insects were normally consumed in ancient Roman society and were considered a delicacy, on one side, and food for poor people, on the other side [34]. Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and naturalist who lived in the first century AD, wrote extensively about the natural world and the use of plants and animals for food and medicine. In his writings, he mentioned the consumption of insects by the ancient Romans, particularly during times of food scarcity [35]. Pliny the Elder, in his book “Naturalis Historia”, noted that locusts and grasshoppers were considered a delicacy and were often prepared by roasting or frying. He also mentioned the consumption of beetles, ants, and caterpillars, and described the use of ants in medicine for their supposed healing properties [36].

Pliny wrote about the Roman practice of eating beetle larvae, which were considered a delicacy and were fattened up in special jars. He also described the consumption of “Cossus”, possibly the larvae of C. cossus, which were considered a delicacy by the Roman elite. Pliny noted that Cossus was consumed with great relish and was a very tasty food. He noted that these insects were a food source for the poor but were also consumed by wealthy people.

While Pliny recognized the nutritional value of insects and their potential as a food source, he also noted that some insects (not described) could be harmful if consumed and warned against eating certain species. Nevertheless, his writings demonstrate that the consumption of insects was not uncommon in ancient Roman society. Source

Sofia Bettiza

In a small room near the Alps in northern Italy, containers filled with millions of crickets are stacked on top of each other.

Jumping and chirping loudly – these crickets are about to become food.

The process is simple: they are frozen, boiled, dried, and then pulverised.

Here at the Italian Cricket Farm, the biggest insect farm in the country, about one million crickets are turned into food ingredients every day.

Ivan Albano, who runs the farm, opens a container to reveal a light brown flour that can be used in the production of pasta, bread, pancakes, energy bars – and even sports drinks.

Eating crickets, ants and worms has been common in parts of the world like Asia for thousands of years.

Now, after the EU approved the sale of insects for human consumption earlier this year, will there be a shift in attitudes across Europe?

Well, nowhere in Europe is there more resistance to eating insects than in Italy, according to data from the global public opinion company YouGov, and the objections come right from the top – the government has already taken steps to ban their use in pizza and pasta production.

“We will oppose, by any means and in any place, this madness that would impoverish our agriculture and our culture,” Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini wrote on Facebook.

But is that all about to change? Several Italian producers have been perfecting cricket pasta, pizza and snacks.

“What we do here is very sustainable,” says Ivan. “To produce one kilo of cricket powder, we only use about 12 litres of water,” he adds, pointing out that producing the same quantity of protein from cows requires thousands of litres of water.

Farming insects also requires just a fraction of the land used to produce meat. Given the pollution caused by the meat and dairy industry, more and more scientists believe insects could be key to tackling climate change.

At a restaurant near Turin, chef Simone Loddo has adapted his fresh pasta recipe, which dates back nearly 1,000 years – the dough is now 15% cricket powder.

It emanates a strong, nutty smell.

Some of the diners refuse to try the cricket tagliatelle, but those who do – including me – are surprised at how good it tastes.

Francesco Tosto/BBC / Diners at the Turin restaurant that serves the insect pasta are trying cricket-based products out of curiosity

Francesco Tosto/BBC / Diners at the Turin restaurant that serves the insect pasta are trying cricket-based products out of curiosityAside from the taste, cricket powder is a superfood packed with vitamins, fibre, minerals and amino acids. One plate contains higher sources of iron and magnesium, for example, than a regular sirloin steak. So, THEY say.

But is this a realistic option for those who want to eat less meat? The main issue is the price.

“If you want to buy cricket-based food, it’s going to cost you,” says Ivan. “Cricket flour is a luxury product. It costs about €60 (£52) per kilogram. If you take cricket pasta for example, one pack can cost up to €8.”

That’s up to eight times more than regular pasta at the supermarket.

For now, insect food remains a niche option in Western societies, as farmers can sell poultry and beef at lower prices.

Francesco Tosto/BBC

Francesco Tosto/BBC“The meat I produce is much cheaper than cricket flour, and it’s very good quality,” says Claudio Lauteri, who owns a farm near Rome that’s been in his family for four generations.

But it’s not just about price. It’s about social acceptance.

“Italians have been eating meat for centuries. With moderation, it’s definitely healthy,” says Claudio.

He believes that insect food could be a threat to Italian culinary tradition – which is something universally sacred in this country.

“These products are garbage,” he says. “We are not used to them, they are not part of the Mediterranean diet. And they could be a threat for people: we don’t know what eating insects can do to our bodies.

“I’m absolutely against these new food products. I refuse to eat them.“

Francesco Tosto/BBC

Francesco Tosto/BBCWhile insect farming is increasing in Europe, so too is hostility towards the idea.

The EU decision to approve insects for human consumption was described by a member of Italy’s ruling far-right Brothers of Italy party as “bordering on madness”.

Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who has referred to Italy as a “food superpower”, created a Made in Italy ministry when she was elected, with the aim of safeguarding tradition.

“Insect products are arriving on supermarket shelves! Flour, larvae – good, delicious,” she said in a tone of disgust in a video.

Amid concerns that insects might be associated with Italian cuisine, three government ministers announced four decrees aimed at a crackdown. “It’s fundamental that these flours are not confused with food made in Italy,” Francesco Lollobrigida, the agriculture minister, said.

Francesco Tosto/BBC

Francesco Tosto/BBCInsect food is not just dividing opinions in Italy.

spacer

Replace meat with bugs – new trend in Poland

The trend was first concocted in Europe to save the earth. And Poland is expected to follow.

However, Polish PiS rightists are saying a big NO to bugs. They post selfies with steaks and proudly vow they won`t give them up. They also accuse the antiPiS opposition of secret plans to deprive Poles of their sacred right to their traditional piece of meat.

Proudly presenting rightist steaks:

In Poland, it has become a hot topic ahead of an election this year. In March, politicians from the two main parties accused each other of introducing policies that would force citizens to eat insects – the leader of the main opposition party, Donald Tusk, labelled the government a “promoter of worm soup”.

Meanwhile, Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands are more receptive to eating insects. In Austria, they eat dried insects for aperitivo, and Belgians are open to eating mealworms in energy shakes and bars, burgers and soups. We already know that these nations are full of REPTIALIANS! Why wouldn’t they eat bugs??

“I have received hate, I have been criticised. Food tradition is sacred for many people. They don’t want to change their eating habits.“

But he has identified a shift, and says more people – often out of curiosity – are ordering cricket-based products from his menu.

With the global population now exceeding eight billion, there are fears that the planet’s resources could struggle to meet the food needs of so many people.

Agricultural production worldwide will have to increase by 70%, according to estimates by the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organisation. Meanwhile they are closing down farms and murdering farm animals everywhere!!

Shifting to eco-friendly proteins – such as insects – might become a necessity. They have not been able yet to make bug farm sustainable. The cost is exorbitant.

Until now, the possibilities for producing and commercialising insect food had been limited. With the EU’s approval, the expectation is that as the sector grows, the prices will decrease significantly.

Ivan says he already has a lot of requests for his products from restaurants and supermarkets.

“The impact on the environment is almost zero. We are a piece of the puzzle that could save the planet.”.

PiS gangsters proved big hypocrite azholes again.

In the spring, politicians of the United Right warned that the European Union “will order Poles to eat worms.” For several weeks, they raised alarms, among others: large illustrations or videos of insects that they posted on social media. They suggested that they were the only ones defending the independence of the Polish plate. The goal was simple: to create a message that the European Union is losing itself in an irrational reality, and United Right politicians are the conservative anchor of Europe.

The problem is that the words from a few months ago were not followed by actions. Last week, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the European Protein Strategy . 307 parliamentarians were in favor of it, including the vast majority of PiS MEPs .

The document, which mostly refers to the use of protein from insects in the agricultural sector, reads, among others: “the processing of protein crops and grasslands generates by-products that can be used in ways that support the development of a circular economy, for example by using them for human consumption , renewable energy, fertilizers, animal feed or green chemicals”, “animal breeding can contribute to the production of protein in a highly digestible form for human nutrition”, “the growing potential of insect protein for human consumption , and especially for animal feed. “There are more references in the resolution directly pointing to people eating “protein from insects”.

Polish PiS rightists are saying a big NO to bugs

To be honest, not all of them. PiS chairman`s niece, Marta Kaczyńska, encourages Poles to go for bug diet.

Marta Kaczyńska in her weekly column in the right wing weekly “Sieci” decided to refer to the law in force since January 1, which allows the sale of insects as food in Polish stores. As it turns out, the daughter of the deseased presidential couple considers it an excellent solution and enumerates the benefits of eating worms.

According to Kaczyńska, recognizing edible insects as a component of our menu is a “return to ancient traditions”. In addition, their introduction to the market is “meeting the growing demand for food.” She points out that although the human population is increasing, “there is not enough land for animal husbandry and plant cultivation”. In contrast, ” insects are food that does not require much space, food or water to grow. They do not pollute the environment or produce greenhouse gases, as is the case with traditionally farmed animals.”

Jarosław Kaczyński’s niece enumerated the advantages of recognizing insects as food. These include:

– ease of breeding insects, because they adapt to life in different climatic conditions

They are not talking about natural living conditions. They are talking about bug farming in | warehouses. Which require temperature and humidity control as well as lighting, heating

and cooling.

– they have less ability to transmit diseases and are edible in 80% Absolutely NOT TRUE!!

– they are a valuable source of protein and minerals, as well as, for example, omega-3 fatty acids

Not enough studying has been done to know what the human body will be able to assimilate from bugs.

Kaczyńska, listing various countries where insects are eaten, said: – In such a great variety of “dishes”, many people can certainly find something not only healthy, but also tasty. The only barrier is our culture, which for centuries has accustomed us to treat insects as disgusting creatures (…). It is only a matter of time before our Polish palates get used to eating insects, etc. (…) .

Amasing woman!

One of the parties that makes up Poland’s conservative government has proposed an “anti-bug law” that would require food products containing insects to be labelled with a special warning.

The proposal comes amid a recent campaign by the ruling coalition and its associated media in which they have claimed that if opposition parties win power at this year’s elections they will seek to restrict traditional meat consumption and make Poles eat insects instead. The opposition has announced no such plans.

https://t.co/vwvrJzIxBJ

Notes from Poland

@notesfrompoland

Polish farmers have backed a proposal for the EU to ban meat-like names – such as “burger” or “sausage” – for vegetarian products. They say it misleads consumers and threatens cultural heritage. The European Parliament will vote on the amendment this week

Polish farmers back EU ban on vegetarian “burger” and “sausage” labelling

|

“Dried mealworm larvae, powdered cricket – these are among the insects that the eurocrats and Rafał Trzaskowski [the opposition mayor of Warsaw] call new food,” said Janusz Kowalski, a deputy agriculture minister, while unveiling the plans in parliament yesterday.

“That is why we, United Poland [Solidarna Polska], have initiated the preparation of legal regulations, following the examples of Hungary and Italy, that will give Polish consumers clear knowledge about food products containing so-called bug additives,” he continued. “This is an anti-bug law.”

United Poland is a hardline, eurosceptic junior partner to the main ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party. Its leader, Zbigniew Ziobro, is justice minister. Under its proposed law, products would have to include a label on their packaging saying: “Warning, this food product contains insect protein.”

“If Rafał Trzaskowski wants to eat mazurek [a traditional Polish Easter cake] make of dried insects, he has the right to do so,” added Kowalski. “We, as conservatives, as Poles, definitely prefer normal Polish food, Polish meat, Polish dairy products.”

sassy scarecrow,

|

Yes, indeed corporate farming is horrendously abusive to animals, to humans and to our environment. But, natural farming is NOT!! Natural farming has been around forever and in total alignment with nature/the environment. Family farms treat their animals totally humanely. In fact, most of the farmers/ranchers I know treat their animals like pets….even as members of their family.

But, you want to allow CORPORATE FARMS to determine how your food will be grown, harvestd and processed?? WHAT??? Corporate farms, like the CORPORATION that is our GOVERNMENT have done NOTHING that is GOOD for us, or for the environment. What is wrong with your thinker????

|

In January this year, the European Commission approved products made from mealworm larvae and house crickets as safe for consumption. They were not the first insect products approved by Brussels, and the commission emphasised at the time that “nobody will be forced to eat insects”.

Sure, nobody is going to hold a gun to your head and demand that you eat bugs. However, when they control the food. How it is raised, harvested and processed. They control what is available for you to buy. They ARE FORCING YOU to eat bugs!! Who do they think they are fooling?

Nevertheless, many conservatives in Poland and elsewhere in Europe saw it as part of a push to undermine traditional culinary cultures, especially meat consumption. God Bless the Polish people, they are smart and discerning and courageous! They stand up for what they know is right!!

Soon after, further controversy was sparked in Poland when the Dziennik Gazeta Prawna newspaper wrote about a report from a group called C40 Cities that recommended cutting meat consumption as part of efforts to reduce emissions.

Warsaw is a member of the C40 group and its mayor, Trzaskowski, has attended and spoken at the organisation’s events. Politicians and media linked with the ruling camp therefore conflated the EU and C40 stories to claim that the Polish opposition want to restrict or ban traditional meat and replace it with insects.

|

|

spacer

In response, Trzaskowski repeatedly made clear that he has no intention of introducing any restrictions on meat consumption in Warsaw. “Please enjoy steaks to your heart’s content,” he tweeted. Other opposition figures also rejected the idea.

A survey conducted by Ipsos and published this week by media outlets OKO.press and TOK FM, however, suggests that the ruling coalition’s campaigning on this issue has had an effect.

Among PiS supporters, 45% say they believe the opposition could introduce restrictions on Poles’ meat consumption if it wins power. By contrast, only 5% of supporters of the main opposition group, Civic Coalition (KO), in which Trzaskowski is a leading figure, believe this.

spacer

spacer

- Acceptable insects: Leviticus 11:20-25 states that locusts, katydids, crickets, and grasshoppers are acceptable to eat because they have jointed legs for hopping on the ground.

- Unacceptable insects: Leviticus 11:20-25 also states that all other flying insects that walk on all fours are detestable and will make a person unclean. Anyone who touches the carcass of an unclean insect must wash their clothes and remain unclean until evening.

- Mark 1:6: Mark 1:6 states that John the Baptist ate locusts and wild honey

spacer

2 Speak unto the children of Israel, saying, These are the beasts which ye shall eat among all the beasts that are on the earth.

3 Whatsoever parteth the hoof, and is clovenfooted, and cheweth the cud, among the beasts, that shall ye eat.

4 Nevertheless these shall ye not eat of them that chew the cud, or of them that divide the hoof: as the camel, because he cheweth the cud, but divideth not the hoof; he is unclean unto you.

5 And the coney, because he cheweth the cud, but divideth not the hoof; he is unclean unto you.

6 And the hare, because he cheweth the cud, but divideth not the hoof; he is unclean unto you.

7 And the swine, though he divide the hoof, and be clovenfooted, yet he cheweth not the cud; he is unclean to you.

8 Of their flesh shall ye not eat, and their carcase shall ye not touch; they are unclean to you.

9 These shall ye eat of all that are in the waters: whatsoever hath fins and scales in the waters, in the seas, and in the rivers, them shall ye eat.

10 And all that have not fins and scales in the seas, and in the rivers, of all that move in the waters, and of any living thing which is in the waters, they shall be an abomination unto you:

11 They shall be even an abomination unto you; ye shall not eat of their flesh, but ye shall have their carcases in abomination.

12 Whatsoever hath no fins nor scales in the waters, that shall be an abomination unto you.

13 And these are they which ye shall have in abomination among the fowls; they shall not be eaten, they are an abomination: the eagle, and the ossifrage, and the ospray,

14 And the vulture, and the kite after his kind;

15 Every raven after his kind;

16 And the owl, and the night hawk, and the cuckow, and the hawk after his kind,

17 And the little owl, and the cormorant, and the great owl,

18 And the swan, and the pelican, and the gier eagle,

19 And the stork, the heron after her kind, and the lapwing, and the bat.

20 All fowls that creep, going upon all four, shall be an abomination unto you.

21 Yet these may ye eat of every flying creeping thing that goeth upon all four, which have legs above their feet, to leap withal upon the earth;

22 Even these of them ye may eat; the locust after his kind, and the bald locust after his kind, and the beetle after his kind, and the grasshopper after his kind.

23 But all other flying creeping things, which have four feet, shall be an abomination unto you.

24 And for these ye shall be unclean: whosoever toucheth the carcase of them shall be unclean until the even.

25 And whosoever beareth ought of the carcase of them shall wash his clothes, and be unclean until the even.

26 The carcases of every beast which divideth the hoof, and is not clovenfooted, nor cheweth the cud, are unclean unto you: every one that toucheth them shall be unclean.

27 And whatsoever goeth upon his paws, among all manner of beasts that go on all four, those are unclean unto you: whoso toucheth their carcase shall be unclean until the even.

28 And he that beareth the carcase of them shall wash his clothes, and be unclean until the even: they are unclean unto you.

29 These also shall be unclean unto you among the creeping things that creep upon the earth; the weasel, and the mouse, and the tortoise after his kind,

30 And the ferret, and the chameleon, and the lizard, and the snail, and the mole.

31 These are unclean to you among all that creep: whosoever doth touch them, when they be dead, shall be unclean until the even.

32 And upon whatsoever any of them, when they are dead, doth fall, it shall be unclean; whether it be any vessel of wood, or raiment, or skin, or sack, whatsoever vessel it be, wherein any work is done, it must be put into water, and it shall be unclean until the even; so it shall be cleansed.

33 And every earthen vessel, whereinto any of them falleth, whatsoever is in it shall be unclean; and ye shall break it.

34 Of all meat which may be eaten, that on which such water cometh shall be unclean: and all drink that may be drunk in every such vessel shall be unclean.

35 And every thing whereupon any part of their carcase falleth shall be unclean; whether it be oven, or ranges for pots, they shall be broken down: for they are unclean and shall be unclean unto you.

36 Nevertheless a fountain or pit, wherein there is plenty of water, shall be clean: but that which toucheth their carcase shall be unclean.

37 And if any part of their carcase fall upon any sowing seed which is to be sown, it shall be clean.

38 But if any water be put upon the seed, and any part of their carcase fall thereon, it shall be unclean unto you.

39 And if any beast, of which ye may eat, die; he that toucheth the carcase thereof shall be unclean until the even.

40 And he that eateth of the carcase of it shall wash his clothes, and be unclean until the even: he also that beareth the carcase of it shall wash his clothes, and be unclean until the even.

41 And every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth shall be an abomination; it shall not be eaten.

42 Whatsoever goeth upon the belly, and whatsoever goeth upon all four, or whatsoever hath more feet among all creeping things that creep upon the earth, them ye shall not eat; for they are an abomination.

43 Ye shall not make yourselves abominable with any creeping thing that creepeth, neither shall ye make yourselves unclean with them, that ye should be defiled thereby.

44 For I am the Lord your God: ye shall therefore sanctify yourselves, and ye shall be holy; for I am holy: neither shall ye defile yourselves with any manner of creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.

45 For I am the Lord that bringeth you up out of the land of Egypt, to be your God: ye shall therefore be holy, for I am holy.

46 This is the law of the beasts, and of the fowl, and of every living creature that moveth in the waters, and of every creature that creepeth upon the earth:

47 To make a difference between the unclean and the clean, and between the beast that may be eaten and the beast that may not be eaten.

spacer

Whether you believe it or not, the GOD of the BIBLE IS GOD!! He is the CREATOR OF ALL THINGS. When your eyes are opened and you are able to see and discern TRUTH, you begin to recognize what a marvelous and awesome CREATOR GOD IS!! He has created everything so perfectly. There is purpose and design in every single thing on earth. When we live as HE intended, everything works perfectly.

There is a reason for every thing He did and EVERYTHING HE SAYS. He told us not to eat certain things because our bodies are not able to process and assimilate them. The things that we are told to eat, work with out bodies to build our cells, and give us energy and strength. Our bodies are able to digest them properly and utilize all the different nutrients they provide.

We are living in the END TIMES, when the KING OF EVIL is ruling. Everything has been turned upside down and backward. Good is called evil and evil is called good. Just as the Bible predicted.

Whether you believe or not, there is RIGHT and WRONG, GOOD and EVIL, TRUTH and DECEPTION. Without GOD you can never dig your way through the lies and deception that is flooding the earth today.

Just as the Devil and his servant want you to accept and embrace EVERY PAGAN religion, they want you to ingest into your body every unnatural, evil, destructive thing they can get into you. They are poisoning us and perverting our bodies.

There is a lot that they are doing to us that we don’t know about. We are not held responsible for that. But, when you see that what they are doing is wrong and you willing participate, for that you are responsible.

Jesus CHRIST/Yahushua Ha Mashiach is coming soon. He could come any time now. This is not a time to be ignorant or will fully disobedient. When He returns you want to be ready to meet Him, face to face, with a clear conscience. You want to bully cognizant and prepared to respond.