Don’t you find it interesting that for thousands of years (millions if you believe what “Scientists” claim) humans have been fairly healthy. Yes, there were some common diseases that would come and go every year. (Perhaps natural process of culling the herd) and occasionally there would be a pathogen that would appear among a group of people or even a nation or nations, there might be a rare epidemic that would complete its lifespan and be gone. These things were not COMMON people. You did not hear of this everyday. Yes, there have always been liver disease from over indulgence, lung issues, heart disease, etc. Mostly from known or identifiable causes, and often with treatments and perhaps cures.

What we are seeing in the world today is not normal or naturally occurring. These things are being CREATED by humans, NOT BY GOD. And worst of all, our entire bodies are being so polluted and attacked by man made chemicals, foreign cells, and deliberate efforts to change our DNA structure, that we have no ability to defend ourselves.

Today’s “Scientists” are playing with things that they do not understand nor control. Yes, they can make things happen, but all those things have consequences of which the “Scientists” either do not know about or do not care about. These MADMEN are driven to push the envelope as far as they can regardless of the cost. They don’t even care if the blow up the entire earth or even the heavens above.

“TRUST THE SCIENCE” is what the scream at us. But, these madmen are not practicing true, honest science and they have no accountability for their actions. They are boys playing with toys. They behave like children.

They may develop technical means of manipulating different parts and aspects of our bodies, but they have to admit that even now they do not understand how the body works. Though they take lives everyday, they cannot give life to anyone. They do not even know why two patients with the exact same symptoms, in the exact same condition, the exact same age and background can be treated in the exact manner even operated on by the exact same surgeon and staff ; and one will live and the other will die. They can’t tell you why.

They can’t even CREATE a disease. ONLY GOD CREATES SOMETHING FROM NOTHING. All they can do is find things that already exist and pervert, twist, manipulate and alter them. They have worked very hard to cross the blood/brain barrier. They have worked very hard to be able to make diseases jump from animals to humans. Now, with the aid of CRISPR TECHNOLOGY they have what they need and they are going to town. Developing all sorts of strange concoctions and deadly germs and fungi. Like children in a candy store.

BECAUSE THERE IS A GOD, and HE determines who lives and who dies. If we look to him for our health, HE steps in and takes care of us. IF we CHOOSE to trust in “Science” than He leaves us to it. We have to suffer the consequences.

This post is about how trusting in science will be our demise.

If you have not viewed the following posts, I strongly urge you to do so.

Zombie Apocalypse

WHAT? ZOMBIES? FOR REAL?

GIANT SQUID NWO ICON

KRAKEN AND OTHER COVID VARIANTS

WHERE MONKEYPOX CAME FROM.

No Monkeying Around – The Medical Take Over Off To A Strong Start

CRISPR – Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4

CRISPR-WUHAN VIRUS-WAKE UP and READ THE SIGNS!

PANDEMIC – OUTBREAK – Diseases, Epidemics, Pandemics and Plagues

LET’S HAVE A SERIOUS TALK ABOUT EPIDEMICS!

Let’s Have a Serious Talk About Epidemics – Part 2 – Candida Auris

COVID 19 – MORE THAN YOU EVER WANTED TO KNOW ABOUT BIOWEAPONS

Biological Attack on Humanity?

Hand Washing/Sanitizing – THE DANGERS KNOWN AND UNKNOWN

The Human Microbiome Is Going Extinct, Scientists Say. The End Will Be Devastating.

And not just for us.

Carol Yepes//Getty Images

- Researchers say the human microbiome that lives in your gut is now endangered.

- The loss of bacteria and microorganisms reduces your chance at a healthy life.

- You’re the one killing off your own microbiome.

The human microbiome is endangered. And that’s not a good thing for your health—or the health of the rest of the world.

A new documentary, The Invisible Extinction, highlights how the human microbiome—also known as the bacteria and microorganisms living within the human body, most prevalent in the gut—is on the verge of extinct. And it’s all your fault.

In a discussion with People, two researchers behind the doc, Martin Glaser and Gloria Dominguez-Bello, say the human microbiome is essential for us to digest food, make vitamins, and train our immune systems. “When we eat,” Blaser tells People, “we are nourishing both our human cells and also our microbial cells.”

The slow death of the human microbiome is thanks to our modern way of life. We use antibiotics to kill off bad bacteria. But antibiotics kill off plenty of the good stuff, too. Blaser says the more antibiotics given to a child, the more likely they are to develop a range of illnesses. Blaser adds that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates about one-third of antibiotic prescriptions are unnecessary, leading to the overuse.

Then there’s the highly processed, chemical-laden food that’s wreaking havoc on our gut health. “The single most important component of the diet to feed the microbiome is fiber,” Dominguez-Bello says. These fibers feed your microbiome, while processed food removes the fiber, posing a negative result for your microbiome.

The researchers want better options for the antibiotic issue, both with improved testing to see if a bacterial infection is really in play, and by developing new antibiotics that don’t have the “collateral damage that are killing every bacterium inside.”

“We are making a complete mess of biodiversity, including microbial,” Dominguez-Bello says. “Microbes are essential in every ecosystem, not only in humans or animals or plants, but also in the oceans. He whole thing is linked together by impact of human activities. We need to preserve microbes because they really modulate functions of Earth. They modulate the climate. They modulate everything. They modulate our own gene expression.”

The human microbiome is a big deal. Let’s not kill it

spacer

Dangerous fungal illness rapidly spreading across country, doctors warn

SAN FRANCISCO – Doctors are warning of a dangerous fungal illness rapidly spreading across the country, especially affecting those living or visiting the California and Arizona areas.

If you think it sounds like something from the cutting room floor of “The Last of Us” series, where a parasitic fungal infection devastates mankind, there are some very base-level similarities.

Valley fever (also called coccidioidomycosis or “cocci”) is a significant cause of pneumonia, said Dr. Brad Perkins, chief medical officer at Karius, a company that provides advanced diagnostics for infectious diseases.

“This is a fungus,” said Perkins, a former Centers for Disease Control and Prevention official who led the anthrax bioterrorism investigation. “Most causes of pneumonia are caused by bacteria. This is a fungus that lives in the soil and is breathed in dusty situations, whether it’s a dust storm or around construction or excavation.”

DOCTORS REMOVE LUNG FROM DOG THAT NEARLY DIED AFTER INHALING FUNGUS FOUND IN SOIL

Valley fever and COVID-19 share many of the same symptoms as a cough, difficulty breathing, fever, tiredness or fatigue. In rare cases, it can spread to other body parts and cause severe disease..

Animals, including pets, can also get Valley fever by breathing in fungus spores from dirt and outdoor dust. However, it cannot spread from one person or animal to another. There are about 200 deaths a year due to the disease.

“Those are mostly people with severe immunocompromising illnesses underlying this infection,” Perkins said. “It can be a devastating infection in those people. That’s pretty rare, fortunately.”

Prevention is challenging, according to Perkins. Risk is mostly associated with travel to high-risk areas.

“People concerned about their risk of developing Valley fever should try to avoid dusty situations, mostly in the summer and in peak heat,” Perkins said.

You should also see your doctor if you develop signs or symptoms of pneumonia.

‘TRUE FORM OF MAGIC’: GLOWING FUNGUS MAKES FOR SURREAL NEON SCENE ALONG DARK WASHINGTON BEACHES

The fungi that cause Valley fever are Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasiii, the CDC reports.

|

Coccidioides immitis, the causative agent of coccidioidomycosis, is endemic in the southwestern United States and parts of Latin America. Primary infection develops after a susceptible host inhales the mycelia. Once in the host, spherules form and then produce endospores. 16,59 Pulmonary signs develop 1 to 3 weeks after infection.

|

|

Coccidioidomycosis is an infection caused by the dimorphic fungi, Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. It is endemic to the Southwest United States, Northern Mexico and parts of Central and South America. The risk of infection among SOT recipients residing in endemic regions in the absence of prophylaxis was reported to be 7% to 9%.

|

|

In the U.S., scientists have found C. immitis primarily in California, as well as Washington State. C. posadasii is found primarily in Arizona, as well as New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Texas, and portions of southern California.

According to the CDC, Southern California, particularly the southern San Joaquin Valley, and southern Arizona, including metropolitan Phoenix and Tucson, have the highest reported rates of Valley fever. The disease is likely also common in parts of West Texas and along the Rio Grande River.

In California, state health officials said the number of reported Valley fever cases has greatly increased in recent years – tripling from 2014 to 2018. Most cases of Valley fever in California (over 65%) are reported from the Central Valley and Central Coast regions, the California Department of Health said.

Perkins has a word to the wise for the thousands of football fans traveling to State Farm Stadium, in Glendale, Arizona, for the Super Bowl to see the Kansas City Chiefs take on the Philadelphia Eagles.

“If you’re just traveling to the airport and to the hotel and to the Super Bowl, you’re probably going to be fine,” Perkins said. “If you’re out hiking in the desert, you might want to give some consideration to your risk for development of Valley fever.”

The Arizona Department of Health Services said 11,523 reported cases of Valley fever was reported in the state in 2020. In total, 94% of cases were reported in 3 counties – Maricopa, Pima and Pinal, which are home to Phoenix and Tucson.

NOT FROM A HORROR FILM: WHEN INSECTS TURN INTO ‘ZOMBIES’

While most people who breathe in the spores don’t get sick, those who develop Valley fever typically feel better on their own within weeks or months. About 5% to 10% of people who get Valley fever will develop serious or long-term lung problems.

“Many people are asymptomatic when they get this infection, so they don’t have any symptoms at all,” Perkins said.

Having an infection, however, is probably protective in the future.

“If you’re one of the lucky ones that that gets infected and doesn’t have symptoms, you probably have some degree of protection in the future,” Perkins adds.

If you do develop symptoms, they look pretty much like typical pneumonia caused by bacteria.

“If you see a physician, whether you’re hospitalized or as an outpatient, they will likely prescribe medicines that are for bacteria and won’t have any impact on this fungus,” Perkins said.

Perkins adds that is one way Karius offers the need for a better diagnostic test for diseases like this one, particularly in immunocompromised patients. A single diagnostic test by Karius, using a single blood draw, can identify whether this is a bacterium or fungi of any type and get doctors the information they need and get patients on the right therapy more quickly.

The increased number of cases are primarily associated with people migrating to areas like Arizona and California, and people traveling there for recreation, Perkins said.

“Many of those may be retirees or older adults that, one, have not been exposed to Valley fever in the past, and, two, maybe immune suppressed at higher risk for disease,” he adds.

The climate crisis may be to blame as well. As heat increases, that may be facilitating the reproduction of the fungus in the soil in these areas.

“It’s important to note that the entire western United States has some level of Valley fever, but it’s much higher in the Phoenix region of Arizona and certain parts of the interior of California,” Perkins said.

A study published in the journal GeoHealth estimated that the range of Valley fever could reach the border with Canada before the end of the century.

spacer

spacer

If you’ve been following HBO’s breakout hit The Last of Us—a story of people navigating a post-apocalyptic world where the cordyceps brain infection (CBI) has turned most of mankind into zombies—then you might be wondering if the“zombie fungus” is real (and if it affects humans). While the show is a freaky science fiction series based on a video game, the alarming spore-filled infection seen in the show is actually real.

The Last of Us is reportedly based on the cordyceps fungus (specifically Ophiocordyceps unilateralis), which is a so-called“zombie fungus” that infects ants. But while the fungus is a real thing, experts say it can’t infect humans. Still, it’s understandable to have questions. Here’s the deal.

What is the cordyceps fungus?

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis is a specialized parasite that infects, manipulates, and then kills ants, usually in a tropical setting, according to one scientific paper on the fungus.

“The fungi spreads through spores. A spore lands on an ant and produces a tube that bores through the cuticle into the ant body,” explains Raymond J. St. Leger, Ph.D., a mycologist and professor in the department of entomology at the University of Maryland, who has worked on Ophiocordyceps unilateralis.

“Once in the hemolymph—insect ‘blood’—the fungus multiplies and spreads through the body of the insect,” says entomologist Roberto M. Pereira, Ph.D., a research scientist with the University of Florida.

St. Leger adds that it does so in a “yeast-like form.” The fungus moves on to grow around the ant’s brain, causing the ant to develop “quite specific” behavior during the zombie stage, he says.

How does the cordyceps fungus spread?

There’s a very specific way this fungus makes its way around ants. Once an ant is infected, it “crawls up a plant stem and bites down hard onto a leaf’s vein with its mandibles (jaws),” St. Leger says, adding, “This ‘death grip’ is caused by the fungus colonizing the mandibles.” The fungus also comes out through the legs of the ant as tubes that basically stick the ant to the leaf. “The ant then dies and the fungus produces a fruiting body from the ant’s head—the brain is one of the last parts of the ant’s insides that the fungus digests,” St. Leger says. But, even if the ant doesn’t spread spores over other ants, the spores are often “spread by wind and water, and eventually land on a new healthy host so the cycle can be repeated and new fungal spores can be produced,” Pereira says.

Even creepier? The ant attaches itself to a “pretty specific spot on the underside of a leaf that is near where other ants are foraging or coming down,” says Ian Williams, an entomologist at Orkin. Once the ant dies, the fungus will release spores and, given the ant’s very strategic position, “There’s a high chance those spores will land on others and infect them as well,” Williams says.

Basically, not only does Ophiocordyceps unilateralis turn ants into zombies, it strategically tries to infect as many other ants as possible in the process—an aspect seen in The Last of Us.

“The zombie thing is of particular interest as a creature without a brain—the fungus—is manipulating the behavior of a creature with a brain,” St. Leger says. Consider us creeped out.

What are the signs an ant has Cordyceps?

When the ant is first infected, it’s not something most people would notice. “It might start doing odd behavior that only very specific scientists might notice,” William says.

Ants, however, can pick up on it. An infected ant initially “starts trembling and cleaning itself,” St. Leger says. That’s a heads-up to other ants to get out. “Other ants recognize this behavior as a danger and will carry an infected ant away from the nest and dump it,” St. Leger says.

So, can Cordyceps infect humans?

That’s why you’re here, right? Experts stress that you don’t need to worry about a The Last of Us situation happening anytime soon—from Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, at least. “It’s really specific to a small group of ants,” Williams says. “It’s co-evolved with these ants to have a specific reproductive strategy.”

Of course, some pathogens do jump from animals and bugs to humans, but it seems unlikely to happen in this situation, says Thomas Russo, M.D., chief of infectious diseases at the University at Buffalo in New York. “There are literally billions of microbes on this planet—it’s a microbial world,” he says. “Only a very small part infect humans and, when it comes to fungi, it’s an even smaller number.”

Pereira points out that it’s possible for humans to have an allergic reaction to the fungus, though, noting that one of his employees once developed a severe case of bronchitis while working with a similar insect fungus. “If the quantities of spores are very high in the air, some people may show allergic signs to the fungus, even if no true infection occurs,” he says. However, it’s worth reiterating, you still won’t turn into a zombie.

Basically, don’t lose sleep at night over fears that you’ll be turned into a zombie by a creepy fungus that targets ants. But, if you’re a fan of the spook factor, then definitely check out The Last of Us via HBO. New episodes drop every Sunday.

Try 200+ at home workout videos from Men’s Health, Women’s Health, Prevention, and more on All Out Studio free for 14 days!

ana-morph –

two faces of the same body – two different expressios

spacer

So, “SCIENCE” created the issues in our body, especially our GUT, by pushing antibiotics in the form of bills, liquids and injections.

Then when we discovered what was happening to us, “Science” stepped in and gave us the “solutions”. Probiotics, bombarding the market with “experts” advising us to ingest they in yogurt as well as a avalanche of commercially produced Probiotics and Prebiotics. Problem solved…Right?? Are you kidding…

spacer

THE LIFE INSIDE ALL OF US

Microbes & me is a new collaborative series between BBC Future and BBC Good Food.

In the series, we’ll be looking at recent research into the microbiome of bacteria that lives in all of us.

We’ll be exploring how it affects our health, what could be having detrimental effects on it, and recommending recipes that might help it thrive.

Probiotics have been touted as a treatment for a huge range of conditions, from obesity to mental health problems. One of their popular uses is to replenish the gut microbiome after a course of antibiotics. The logic is – antibiotics wipe out your gut bacteria along with the harmful bacteria that might be causing your infection, so a probiotic can help to restore order to your intestines.

But while it might sound like sense, there is scant solid evidence suggesting probiotics actually work if taken this way. Researchers have found that taking probiotics after antibiotics in fact delays gut health recovery.

Part of the problem when trying to figure out whether or not probiotics work is because different people can mean a variety of things with the term ‘probiotic’. To a scientist, it might be seen as a living culture of microorganisms that typically live in the healthy human gut. But the powdery substance blister packs on supermarket shelves can bear little resemblance to that definition.

Even when researchers use viable, living bacterial strains in their research, the cocktail varies from one lab to another making it tricky to compare.

“That’s the problem – there aren’t enough studies of any one particular probiotic to say this one works and this one doesn’t,” says Sydne Newberry of Rand Corporation, who carried out a large meta-analysis on the use of probiotics to treat antibiotic-induced diarrhoea in 2012.

You might also like:

- How your gut bacteria changes the way you feel

- The microbes in your body you couldn’t live without

- How bacteria can save children’s lives

Newberry’s findings, reviewing 82 studies of nearly 12,000 patients, did find a positive effect of probiotics in helping to reduce the risk of antibiotic-induced diarrhoea. But due to the variation – and sometimes lack of clarity – on which bacterial strains had been used, there was no particular probiotic or cocktail of probiotics that could be pinpointed and recommended as working.

Since that 2012 study, the evidence in support of probiotic use after antibiotics hasn’t moved on a great deal.

It’s widely believed that antibiotics wipe out your gut bacteria – along with the harmful bacteria that might be causing your infection (Credit: Getty Images)

“That’s what’s so troubling,” says Newberry. “There are a few more studies than when we did the review, but not enough to conclusively say whether probiotics work or not. And not enough to say which ones work.”

A particular concern is a lack of research on the safety of taking probiotics. While they are generally assumed to be safe in healthy people, there have been worrying case reports of probiotics causing problems – such as fungus spreading into the blood – among more vulnerable patients.

A recent study by scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel found that even among healthy people, taking probiotics after antibiotics was not harmless. In fact, they hampered the very recovery processes that they are commonly thought to improve.

The researchers, led by Eran Elinav, gave 21 people a course of broad-spectrum antibiotics for one week. After this, they had a colonoscopy and an upper-gastrointestinal endoscopy to investigate the state of their microbiome throughout the gut.

The surprising finding was that the group who received the probiotic had the poorest response in terms of their microbiome

“As expected, a lot of major changes occurred in the function of the microbes – many of which died because of the antibiotics,” says Elinav.

The volunteers were divided into three groups. The first was a wait-and-see group, with no intervention after the antibiotics. The second group was given a common probiotic for a month. The third was given perhaps the least savoury option: a faecal transplant. This group had a small sample of their own stool – taken before the antibiotic treatment – returned to their colon once the treatment was over.

The surprising finding was that the group who received the probiotic had the poorest response in terms of their microbiome. They were the slowest group to return to a healthy gut. Even at the end of the study – after five months of monitoring – this group had not yet reached their pre-antibiotic gut health.

Probiotics won’t work exactly the same for everyone because gut biomes are different (Credit: Getty Images)

“We have found a potentially alarming adverse effect of probiotics,” says Elinav.

The good news, incidentally, is that the group who received a faecal transplant did very well indeed. Within days, this group completely reconstituted their original microbiome.

“So many people are taking antibiotics all over the world,” says Elinav. “We can aim to better understand this potentially very important adverse effect that we didn’t realise existed.”

And the evidence is mounting that taking probiotics when gut health is weak is not such a good idea. Another recent study has found that probiotics don’t do any good for young children admitted to hospital for gastroenteritis. In a randomised controlled trial in the US, 886 children with gastroenteritis aged three months to four years were given either a five-day course of probiotics or a placebo.

Given the very heavy involvement of the industry, clear conclusions as to whether probiotics are truly helpful to humans remain to be proven – Erin Elinav

The rate of continued moderate to severe gastroenteritis within two weeks was slightly higher (26.1%) in the probiotic group than in the placebo group (24.7%). And there was no difference between the two groups in terms of the duration of diarrhoea or vomiting.

Despite evidence such as this, the demand for probiotics is large and growing. In 2017, the market for probiotics was more than $1.8bn, and it is predicted to reach $66bn by 2024.

“Given the very heavy involvement of the industry, clear conclusions as to whether probiotics are truly helpful to humans remain to be proven,” says Elinav. “This is the reason why regulatory authorities such as the US’s Food and Drug Administration and European regulators have yet to approve a probiotic for clinical use.”

Taking probiotics when your gut health is weak may not be a good idea (Credit: Getty Images)

But that is not to write off probiotics completely. The problem with them may not be with the probiotics themselves, but the way we are using them. Often probiotics are bought off the shelf – consumers may not know exactly what they are getting, or even whether the culture they are buying is still alive.

Elinav and his colleagues have also carried out research on who will benefit from probiotics and who won’t. By measuring the expression of certain immune-related genes, the team was able to predict who would be receptive to probiotic bacteria colonising their gut, and for whom they would simply “pass through” without taking hold.

“This is very interesting and important as it also implies that our immune system participates in the interactions with [probiotic] bacteria,” says Elinav.

The lack of consistency in the findings on probiotics comes in part because they are being treated like conventional drugs

This opens the door to developing personalised probiotic treatments based on someone’s genetic profile. Such a system is “realistic and could be developed relatively soon”, says Elinav, but at this stage it remains a proof of concept. To become a reality, it will need more research on probiotic tailoring and testing more bacterial strains in larger groups of people.

This kind of personalisation may release the full potential of probiotic treatments for gut health. At the moment, the lack of consistency in the findings on probiotics comes in part because they are being treated like conventional drugs. When you take a paracetamol tablet, you can be more or less sure that the active component will do its job and work on receptors in your brain, dulling your sensation of pain. This is because most people’s pain receptors are similar enough to react in the same way to the drug.

But the microbiome is not just a receptor – it is closer to an ecosystem, and sometimes likened to a rainforest in its complexity.

As a result, finding and tailoring a probiotic treatment that will work on something as intricate and individual as your own internal ecosystem is no easy task. And with that in mind, it’s not so surprising that a dried-out pack of bacteria from a supermarket shelf may well not do the trick.

—

Join 900,000+ Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

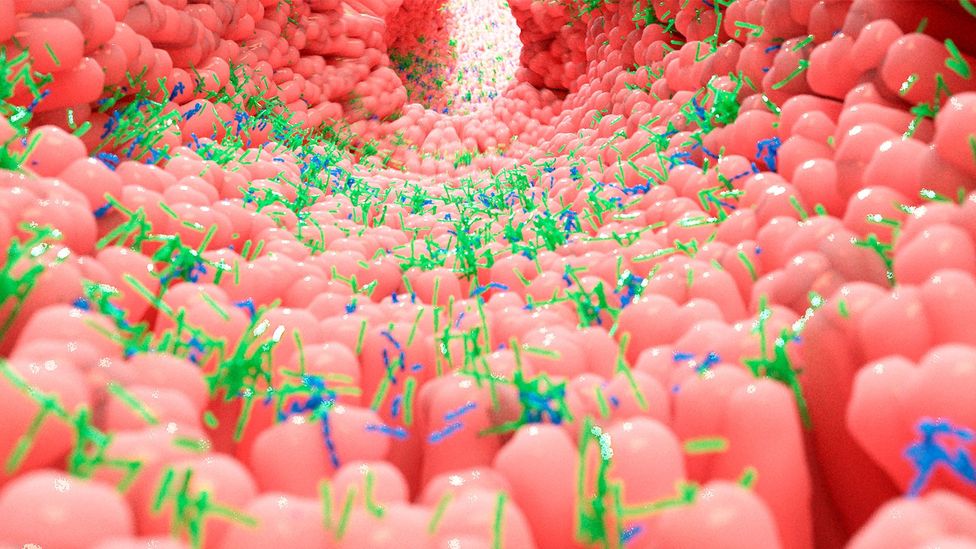

Your gut is a bustling and thriving alien colony. They number in their trillions and include thousands of different species. Many of these microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea and eukarya, were here long before humans, have evolved alongside us and now outnumber our own cells many times over. Indeed, as John Cryan, a professor of anatomy and neuroscience at University College Cork, rather strikingly put it in a TEDx talk: “When you go to the bathroom and shed some of these microbes, just think: you are becoming more human.”

Collectively, these microbial legions are known as the “microbiota” – and they play a well-established role in maintaining our physical health, from digestion and metabolism to immunity. They also produce vital compounds the human body is incapable of manufacturing on its own.

But what if they also had a hotline to our minds? In our new book, Are You Thinking Clearly? 29 Reasons You Aren’t And What To Do About It, we explore the dozens of internal and external factors that affect and manipulate the way we think, from genetics, personality and bias to technology, advertising and language. And it turns out the microbes that call our bodies their home can have a surprising amount of control over our brains.

Over the last few decades, researchers have started to uncover curious, compelling – and sometimes controversial – evidence to suggest that the gut microbiota doesn’t just help to keep our brains in prime working order by helping to free up nutrients for it from our food, but may also help to shape our very thoughts and behaviour. Their findings may even potentially bolster how we understand and lead to new treatments for a range of mental health conditions, from depression and anxiety to schizophrenia.

The picture is still very far from complete, but in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has had a deleterious impact on people’s mental health in many parts of the world, unpicking this puzzle could be more important than ever.

Our guts are a menagerie of different species of bacteria, some of which appear to communicate with our brains (Credit: Rodolfo Parulan Jr/Getty Images)

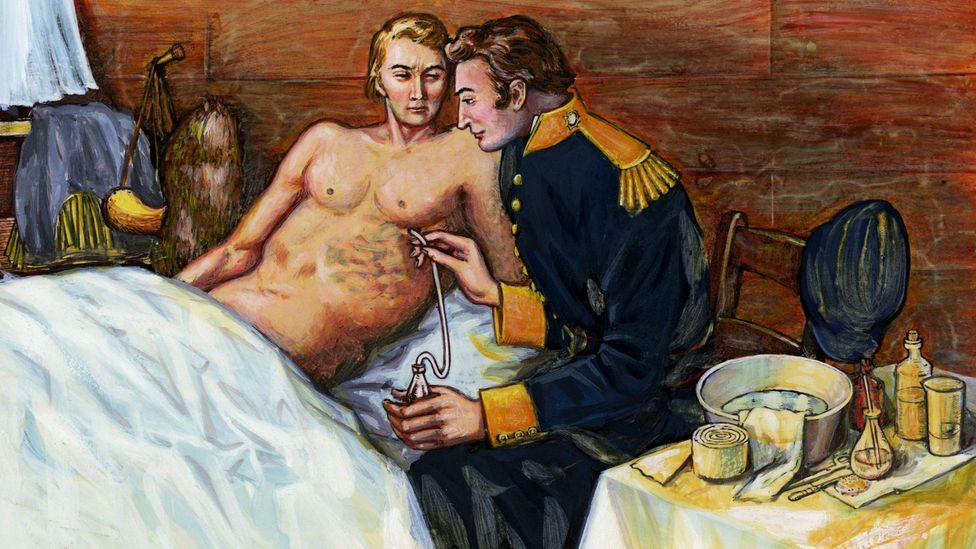

One of the research field’s key origin stories took place in the North American wilderness – and, be warned, it makes for some stomach-churning reading. The year was 1822 and a young trader named Alexis St Martin was loitering outside a trading post on what is now called Mackinac Island, in what is now Michigan, when a musket accidentally went off next to him, firing a shot into his side from less than a yard (91cm) away. His injuries were so bad that part of his lungs, part of his stomach and a good portion of his breakfast that day spilled out through the wound in his left side. Death seemed certain, but an army surgeon named William Beaumont rode to the rescue and saved St Martin’s life, although it took the best part of a year and multiple rounds of surgery.

What Beaumont couldn’t repair, however, was the hole in his patient’s stomach. This persistent fistula would remain a grim and lasting legacy of the accident, but Beaumont wasn’t one to pass up a good opportunity – however unpleasant. Realising that the hole provided a unique window into the human gut, he spent years investigating the intricacies of St Martin’s digestion. Exactly how willing a volunteer St Martin was is open to debate as Beaumont employed him as a servant while conducting research on him – the murky arrangement almost certainly wouldn’t be considered ethical today. Among the findings Beaumont uncovered during his studies of St Martin’s guts, however, included how they were affected by its owner’s emotions, such as anger.

Through this finding, Beaumont, who would go on to be lauded as the “father of gastric physiology“, had hit upon the idea of a “gut-brain axis” – that the gut and the brain aren’t entirely independent of one another but instead interact, with one influencing the other and vice versa. And now we know that the microorganisms within our gut make this process even more complex and remarkable.

“More and more research is revealing that the gut microbiome can influence the brain and behaviour across a variety of different animals,” says Elaine Hsiao, associate professor in integrative biology and physiology, at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

It’s important to remember that the microbes were here before humans existed, so we have evolved with these ‘friends with benefits’ – John Cryan

How exactly our microbiota might be influencing our mind is a growing, pioneering and still relatively novel field. But there have been advances over the last 20 years or so, particularly in animals. And, slowly, a case is being built to suggest that these microorganisms aren’t just a vital part of our physical selves, but also our mental and emotional selves, too.

“In medicine, we tend to compartmentalise the body,” says Cryan. “So, when we talk about issues with the brain, we tend to think about the neck upwards. But we need to frame things evolutionarily. It’s important to remember that the microbes were here before humans existed, so we have evolved with these ‘friends with benefits’. There has never been a time when the brain existed without the signals coming from the microbes.

“What if these signals are actually really important in determining how we feel, how we behave and how we act? And could we modulate these microbes therapeutically to improve thinking, behaviour and brain health?”

You might also like to read:

- Why your microbes like a good workout

- How language warps the way you perceive time

- The hidden way pollution affects us

Hsiao is one of the researchers leading the way in this field and her lab at UCLA has explored the part these microorganisms might play in everything from foetal brain development to cognition and neurological conditions such as epilepsy and depression. She has also investigated how these microbes might be influencing our brains and thinking.

“Specific gut microbes can modulate the immune system in ways that impact the brain and also produce molecules that signal directly to neurons to regulate their activity,” she says. “We find that gut microbes can regulate the early development of neurons in ways that lead to lasting impacts on brain circuits and behaviours. We also find that under shorter timescales, gut microbes can regulate the production of biochemicals, like serotonin, that actively stimulate neuronal activity.”

Indeed, research suggests our microbes may be communicating with our brains through numerous pathways, from immunity to biochemicals. Another candidate is the vagus nerve, which acts as the superfast “internet connection” between our brain and internal organs, including the gut. The bacteria Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB1, for example, appears to improve the mood of anxious and depressed mice. This beneficial effect is removed, however, when the signals travelling along the vagus nerve are blocked, suggesting it could be being used as a communication pathway by the bacteria.

William Beaumont’s research on the digestive juices of Alexis St Martin gave some of the first hints of the interaction between our guts and brains (Credit: Getty Images)

Much of the research in this field is conducted in mice (and other small animals). And mice, of course, aren’t humans. But given the mindboggling complexities of establishing causality between microbial signals and changes in human thought and behaviour, animal studies have provided some intriguing insights into the strange interactions between bacteria and brain. Research, for example, shows that “germ-free” rats and mice (those without any microbiota after being reared in sterile conditions) are more prone to anxiousness, and less sociable than those with an intact microbiota. Germ-free mice, and those given antibiotics have also been found to be more hyperactive, prone to risky behaviour and less able to learn or remember. Antibiotics, which can reduce the microbiota in an animal, also reduce shoaling behaviour in zebrafish, while probiotics boost it.

Again, the human brain is vastly more complex than that of a rodent or fish, but they do share some similarities and can offer clues. It makes sense that bacteria, wherever they live, might benefit from helping their hosts to be more sociable and less anxious. By interacting with other people, for example, we help our bacteria spread. And whether or not they’re really pulling our strings, it’s in our microbes’ evolutionary interests to make their environment as conducive to survival as possible.

But do communicative microbes, congregating zebrafish or friendly mice really matter? Hopefully, yes, say the researchers. Ultimately, a better understanding of these processes could lead us towards ground-breaking new treatments for a range of mental health conditions.

Psychobiotics might one day be used to nurture populations of “good” bacteria and treat a variety of mental health conditions

“We’ve coined the term ‘psychobiotics‘ for [microbiota-based] interventions that have a beneficial effect on the human brain,” says Cryan. “And there are more and more of these psychobiotic approaches coming.”

There are caveats, of course. While some strains of bacteria appear to have a positive effect on the human mind, many others don’t and researchers have yet definitively to establish why – and how. Humans are also unfathomably complex, and when it comes to thinking and mental health, there are countless other factors at play, from genetics and personality to the environment around us.

“We need many more large-scale human studies to take into account these individual differences,” says Cryan. “And maybe not everyone will respond to a single bacteria in the same way because everyone will have a slightly different baseline microbiota anyway.”

Disclaimers aside, however, more research could bring fresh hope. “The good news is that you can change your microbiota, while there’s not a whole lot you can do to change your genetics – except blame your parents and your grandparents,” Cryan adds. “The fact that you can modify your microbiota potentially gives you agency over your own health outcomes.” Indeed, pro- and prebiotic supplements, simple dietary changes, such as eating more fermented foods and fibre – and even, perhaps, meditation – can help alter our microbiota in ways that benefit our minds.

Philip Burnet, an associate professor in the University of Oxford’s department of psychiatry, notes that many mental health conditions have been associated with changes in the microbiota. Often, this imbalance or “dysbiosis” is characterised by a reduced amount of certain bacteria, particularly those that produce short-chain fatty acids (such as butyrate, which is widely believed to improve brain function) when they break down fibre in the gut.

Indeed, a 2019 study by Mireia Valles-Colomer, a microbiologist at KU Leuven University of Leuven in Belgium at the time, and her colleagues found a correlation between the amount of these butyrate-producing bacteria and wellbeing. Specifically, the researchers noted in the study that: “Butyrate-producing Faecalibacterium and Coprococcus bacteria were consistently associated with higher quality of life indicators. Together with Dialister, Coprococcus spp. were also depleted in depression, even after correcting for the confounding effects of antidepressants.”

Antibiotics can change the shoaling behaviour of Zebrafish (Credit: Getty Images)

Human studies on the communication between the gut, the brain and the microbiota are still relatively few and far between. And Burnet urges caution: “It is not known whether these altered levels in gut bacteria cause low mood or whether microbial numbers change because people who are depressed might modify their eating habits or eat less.”

Nevertheless, he has been exploring how prebiotics (which encourage bacteria to grow) and probiotics (live bacteria) might one day be used as psychobiotics to nurture populations of “good” bacteria – and treat a variety of mental health conditions.

For example, one 2019 study by Burnet, Rita Baião, a psychologist also at the University of Oxford, and their colleagues uncovered some particularly interesting findings. Although the study was funded by a company that manufactures probiotic bacteria, it used a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial – considered to be a gold standard study design during which neither participants nor researchers are aware whether they are receiving the treatment or not. The researchers investigated the effect a multispecies probiotic might have on emotional processing and cognition in people with mild to moderate depression. But the study also monitored their mood before and after the experiment using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which measures depression severity.

The participants, who weren’t taking any other medication, were either given a placebo or a commercially available probiotic – which contained 14 species of bacteria, including Bacillus subtilis, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium infantis for four weeks.

The results were fascinating, not least that the participants on the probiotic experienced a significant subjective improvement in mood compared with the group on placebo, essentially becoming less depressed according to the PHQ-9. Changes in the participants’ levels of anxiety, which were also measured, were not observed.

This was a small (71 participants), brief study and more research is needed to prove causality. But it’s an early indication that “psychobiotics” may one day be a helpful treatment for those with depression – particularly those who are reluctant to seek medical help or take traditional antidepressants, says Burnet. Indeed, psychobiotics won’t replace existing medications – but may eventually provide a helpful adjunct.

“They won’t make everyone happier,” says Burnet, but probiotics could one day complement more established mental health treatments. “Only time will tell whether we will have psychobiotics,” he adds. “But the field is really moving forward… This area of research is dominated by animal studies, however, so we do need more human studies using larger numbers of participants.”

But the potential of psychobiotics has captured imaginations.

Those who had used antibiotics for long periods of time scored lower on cognitive tests such as learning, working memory and attention tasks

“We also attracted a lot of interest from the public,” adds Burnet. “People are extremely interested in maintaining their health and wellbeing with natural supplements and encouraging the growth of good bacteria to support mental health has captured the imagination of the general public. Especially now, when people are more anxious and depressed as a result of the pandemic.”

With Amy Chia-Ching Kao and others, Burnet has also explored the role these microorganisms might play in psychosis – and whether prebiotics (which help to promote the growth of bacteria in the gut) might help people with the condition think more clearly.

Many people are aware that psychosis can cause hallucinations, delusions and a detachment from reality. But people with psychosis also often encounter difficulties with cognitive functions such as attention, memory and problem-solving, which can impact their ability to hold down jobs and relationships. While medication can be used to treat the hallucinations and delusions, improving sufferers’ cognitive impairments has proved more difficult.

A double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study by Burnet and Chia-Ching Kao, however, suggests a possible way forward. “We found that giving a prebiotic to people with psychosis did improve cognitive function according to the clinical scales,” says Burnet.

At the start of the study, the participants were on medication and free of psychotic symptoms – but were still experiencing the cognitive impairment typical of psychosis. Over 12 weeks, they were given a prebiotic or a placebo while their metabolism, immunity and level of cognitive impairment was measured over time. At the end of the 12 weeks, they were then switched, so both groups had an equal amount of time on the prebiotic and the placebo.

And the effect was small but significant. The prebiotic improved overall cognitive function, particularly attention and problem solving, leading the researchers to conclude that the improvement was sufficient to boost social and mental wellbeing. There was no evidence of the participants’ immunity or metabolism changing so it wasn’t clear how the prebiotic may have triggered this effect. But it’s another small step towards understanding the relationship between our microbiota and our mental health and the potential development of new treatments for disorders that affect our thinking.

There are hints that the gut microbiota may affect cognitive skills more broadly, too. It is well known that antibiotics disrupt the gut microbiota, but do they affect our cognition? One recent study, which monitored the health and wellbeing of 14,542 female nurses for several years while they worked for the NHS in the UK, found that those who had used antibiotics for long periods of time (more than two months) scored lower on cognitive tests such as learning, working memory and attention tasks than those who hadn’t taken such medication. Importantly, the cognition of the women who had taken antibiotics was slightly poorer when they were followed up seven years later. Although this is only a correlation, the researchers think it could be due to antibiotics-induced changes in the gut.

Our gut microbes may even play a role in how sociable we are if research in rodents are to be believed – and we pick up microbes through contact with others (Credit: Getty Images)

There’s still a very long way to go, though, to understand this properly. This is a fascinating but highly complex field, and research requires funding. The rewards, however, could be profound. “There are only a handful of specific microbes that have been studied so far,” says Hsiao. “Not necessarily because they are the most significant, but because we as scientists have much more to do to really understand the enormous diversity of microbes in the gut and how they function individually and as communities.

“I’m most excited about the opportunity to uncover new mechanistic understanding of how we and our microbial symbionts can work together to promote health and thwart disease.”

In the meantime, perhaps we should all pay a bit more attention to our microbiota. A Mediterranean diet that’s high in fibre, particularly from vegetables, is likely a good place to start. And fermented foods, such as kimchi and kefir (a fermented milk drink) may also be beneficial. In a small study with 45 participants, for example, Cryan and colleagues showed that those who were put on a diet that included a lot of fibre, prebiotics and fermented food (such as onions, yoghurt, kefir and sauerkraut), reported feeling less stressed than a control group which was on a different diet.

“What I like about fermented foods is that they democratise the science,” says Cryan. “They don’t really cost much and you don’t have to get them from some fancy store. You can do it yourself. In this field, we want to provide mental health solutions to people from all socioeconomic areas.”

The relationship we have with our microbiota is “a bit like a federation”, adds Cryan. “These microbes are our fellow travellers.” We’d do well to remember that – for the sake of both our physical and, quite possibly, mental health.

* Are You Thinking Clearly? 29 Reasons You Aren’t, And What To Do About It by Miriam Frankel and Matt Warren is published by Hodder Studio.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

spacer