My goodness… Mr. Bill Gates APPEARS to be such an expert in every field, we ought to just call him MR. WIZARD! Don’t you think? NOT!! He is just the public face of the ruling elite and the United Nations. THE PROMOTER. Whatever evil thing they have in mind to accomplish they throw the money at it and put his face and name on it.

EVIL is what he is, he and his little wife, too.

The United Nations is working to destroy what is called WESTERN SOCIETY and promote the ancient PAGAN world. FOOD certainly is a HUGE part of their PLOT. First of all, because human beings cannot live without food and water. But, more importantly, there is a spiritual aspect to our food/our Sustenance.

There is a Creator. He is THE ONLY TRUE AND LIVING GOD, creator of ALL THINGS He is the giver and sustainer of LIFE.

- Genesis 1: In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. 2 And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

- Psalms 36:9: “You are the giver of life. Your light lets us enjoy life”

- Psalm 139:14: “Life – a Precious Gift from God”

- 1 John 5:11-13: “God has given us eternal life, and this life is in his Son

Other Bible passages that discuss God as the giver of life include Wisdom 1:13-15, 2:23-24, and Mark 5:21-43. Jesus Christ also described himself as “the Way, the Truth, and the Life” and could raise himself from the dead because he is God.

LIFE is in the seed created by GOD. If you start a search on Bible Gateway for the word “seed” you will find, 257 Bible results. Way too many to include here. But you should look at all of them.

ALL LIFE springs forth from SEED, which GOD created. That is why the ruling elite have been so focused on removing the seed from all living things. They claim a patent on ALL seed. They want to control all life.

-

And God said, Let the earth bring forth grass, the herb yielding seed, and the fruit tree yielding fruit after his kind, whose seed is in itself, upon the earth: and it was so.

-

And the earth brought forth grass, and herb yielding seed after his kind, and the tree yielding fruit, whose seed was in itself, after his kind: and God saw that it was good.

-

And God said, Behold, I have given you every herb bearing seed,which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree, in the which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you it shall be for meat.

Grains are basically seeds of the grasses from which we make bread.

If you have not seen my last post, I suggest you view it first and then come back to this one. Here is the link:

GRAIN the most basic source of Nourishment

spacer

Our Heavenly Father does not only provide food, HE provides EVERYTHING that we need. He created our World, He holds it all together, He watches over us and HE sees that we get everything we need.

Deuteronomy 2:7 (KJV) “….These forty years the LORD your God has been with you; you have not lacked a thing.”

Philippians 4:19 (KJV) “But my God shall supply all your needs according to his riches in glory by Christ Jesus.”

Matthew 6:31, 33 (KJV) “Therefore take no thought, saying, ‘What shall we eat? or, What shall we drink? or, Wherewithal shall we be clothed? … But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you.”

Acts 14:17 (KJV) “…and yet He did not leave Himself without witness, in that He did good and gave you rains from heaven and fruitful seasons, satisfying your hearts with food and gladness.”

Psalms 146:7-9 (NLT) “5 Happy is he that hath the God of Jacob for his help, whose hope is in the Lord his God: 6 Which made heaven, and earth, the sea, and all that therein is: which keepeth truth for ever:7 Which executeth judgment for the oppressed: which giveth food to the hungry. The Lord looseth the prisoners:8 The Lord openeth the eyes of the blind: the Lord raiseth them that are bowed down: the Lord loveth the righteous: 9 The Lord preserveth the strangers; he relieveth the fatherless and widow: but the way of the wicked he turneth upside down. 10 The Lord shall reign for ever… “

spacer

Today we are going to look at some “grains” that the United Nations, Bill Gates and the STAKEHOLDERS are trying to push onto the Western World and WHY! Hopefully, by the end of this post you will have seen enough to realize that there is a very sinister purpose behind this push.

Could a grain older than the wheel be the future of food?

Recommended by LinkedIn

What grain did your family grow up eating?I’m from the United States, where wheat and corn are king. But if I had been born in East Asia, I probably would’ve eaten a lot more rice as a kid.

If you grew up in West Africa, you might have eaten an ancient grain called fonio. Fonio has been feeding families in West Africa for more than 5,000 years, longer than any other cultivated grain on the continent. That makes it older than toilets, the wheel, and even writing. It’s a super small grainwith a texture that reminds me a bit of couscous when cooked in hot water. Its nutty taste is delicious on its own but is also good when ground into flour.

Fonio is just one part of a much bigger family of remarkable ancient grains: the millets.Perhaps you’ve heard of finger millet.It’s a staple in Uganda and parts of Kenya and Tanzania,and it’s beloved in India where it is called ragi.Or maybe you’ve heard of teff, a longtime favorite in Ethiopia where it’s used to make injera.

Millets have been around for centuries, but they’re currently experiencing a resurgence—both for consumers who enjoy their taste and for farmers who appreciate how reliable they are to grow.

Fonio, in particular, is like farming on easy mode. You wait until a good rain comes, lightly till the soil to loosen it up, and then scatter the seeds on the ground.Two months later, you harvest the grain.

| Wheat planted in the spring will be ready to harvest after about 4 months from planting. If it’s planted in the fall it will be ready to harvest about 8 months after planting (because so much of its time is spent dormant in the winter). Wheat at 2 weeks looks like long grass. Aug 8, 2023 Source |

spacer

Farmers in Senegal harvest fonio stalks to be processed.

No wonder West African farmers call it the “lazy farmer’s crop”!Fonio grows in the Sahel, a semi-arid region just south of the Sahara Desert.To thrive there, a crop must be drought-tolerant and able to grow in poor quality soil.Fonio not only handles the dry conditions with ease but even rejuvenates the soil as it grows.

As climate change continues to make growing seasons more unpredictable, crops like the millets will become more and more important. The Gates Foundation has been working with partners like CGIAR for years to make staple crops like corn and rice more climate resilient.Millets naturally have many of the qualities farmers look for in a crop, and they could play an important role in helping farmers adapt to a warming world.

They can also help us fight malnutrition. When Europeans first arrived in West Africa, they called fonio “hungry rice” because it grew so quickly that you could eat it at times when other foods weren’t available. Today, many people would probably call it a “superfood.”

Consider this:

- Fonio is a great source of protein, fiber, iron, zinc and several key amino acids.

- Finger millet has 10 times the calcium of wheat.

- Teff is the only grain that is high in vitamin C.

In a world where food security is increasingly uncertain in some parts of the world,these foods could be a game changer.I’ve written a lot about how malnutrition is the first problem I would solve if I had a magic wand. Having access to a high-quality nutrition source could help more kids’ development stay on track.

Nutritious and drought-tolerant, finger millet could bolster food security in Africa.

It makes a delicious porridge, too.

So if millets have so much going for them, why aren’t they eaten everywhere?

In the case of fonio, the answer is simple: Until recently, it was hard to process on a commercial scale. The part you eat is surrounded by a hard hull, which was traditionally removed by skilled women using either a mortar and pestle or their feet to crack the shell. It’s a time- and labor- intensive process that makes it hard to turn a profit.In Senegal, only 10 percent of the fonio grown is sold at market—nearly all of it is consumed directly by farmers and their families.

Traditionally, harvesting fonio is hard work. Skilled women use their feet to remove the hard hull surrounding the part you eat.

It’s time intensive as well, taking up to seven hours to clean, wash, dry and pre-cook the grain.

Luckily, that’s changing. Terra Ingredients —an American company that is helping to bring the grain across the Atlantic—recently partnered with a Senegalese company called CAA to build a commercial processing facility right in Dakar. I got to visit it during my trip, and it was inspiring to see how they’re enabling local farmers to earn a better living.

|

national capital, Senegal

Recent News

|

spacer

ST. LOUIS – Check out the following related posts:

Chandler Illumination – truth unveiledBACK TO THE ROOTDawn’s Rooster |

Initiatives are also underway to improve the market presence of crops like teff, the millet used to make injera, which is gaining international popularity as a gluten-free option.It’s even on the rise within Ethiopia. Thanks to the increased availability of teff flour and ready-made injera, the country has seen a nearly 50 percent increase in teff mills, injera-making enterprises, and retail outlets. Food scientists are also developing new processes and products for finger millet. It’s now eaten in schools across Kenya as part of the ugali porridge served during lunch.

Move over quinoa, Ethiopia’s teff poised to be next big super grainThis article is more than 10 years old

Rich in calcium, iron and protein, gluten-free teff offers Ethiopia the promise of new and lucrative markets in the west

|

||

|

Teff |

||

| Teff – that is basic to Ethiopian cuisine, the grain is central to many religious and cultural ceremonies | ||

| Teff – is a fine grain—about the size of a poppy seed—that comes in a variety of colors, from white and red to dark brown. It is an ancient grain from Ethiopia and Eritrea, and comprises the staple grain of their cuisines. While it grows predominantly in these African countries, with fertile fields and ecologically-sensitive farming methods, Idaho also produces some of the best quality Teff in the world | ||

|

spacer

Yet, many people still just don’t know about the magic millets. Despite their potential, all of the millets I’ve mentioned are what experts call “neglected and underutilized crops,” a term that refers to crops that have fallen into disuse and been historically ignored by agricultural R&D.

That’s changing, too, in part due to the efforts of one person: Chef Pierre Thiam .He’s a Senegalese chef who has made it his mission to create more opportunity for African farmers and spread the word about what he calls “lost crops.” (He’s even hosting a conference focused on them in Dakar later this year.) I was lucky enough to get a lesson in cooking fonio from him at the Gates Foundation’s Goalkeepers event in 2022—the mango salad we made was delicious.

I had a great time learning how to cook fonio with Chef Pierre at Goalkeepers in 2022.

Chef Pierre understands that one grain—or even a whole magic family of grains—isn’t the answer to the world’s food security problems. We need to build strong, diverse food systems that pull from lots of different sources. But if you want to understand how to help farmers adapt to climate change and make crops more resilient, ancient grains like the millets are a great place to start.They’ve survived for centuries, so they’re clearly doing something right!

spacer

Grain Industry Insights in Africa

Volume of Grain Production

When it comes to grain production, Ethiopia led the charts with 30.179 M tons, followed closely by Nigeria with 29.647 M tons. Egypt held the third position with 22.385 M tons, while South Africa and Tanzania produced 19.153 M tons and 11.311 M tons, respectively. These figures suggest that while some African countries have robust production capacities, others are still largely dependent on imports to meet their grain demands.

Most Popular Types of Grain

Maize (corn), wheat, and rice are among the most popular grains cultivated and consumed on the African continent.Maize, adaptable to various climates, is widely grown across sub-Saharan Africa. Wheat is prevalent in North African countries, where bread and other wheat-based foods are dietary staples. Rice consumption is also significant, particularly in West African nations, given its ease of integration into traditional dishes.The volumes of these grains, however, fluctuate annually due to factors like climate variability and market forces.

Drivers of Market Growth and Limitations

Economic development, population growth, and urbanization are key drivers of market growth in Africa’s grain industry.As more people move to cities, the demand for processed and convenient food items, many of which are grain-based, rises. However, growth is not without its limitations. Poor infrastructure, fluctuating climatic conditions, and limited access to technology hinder production capabilities. Policies aiming at improving agricultural practices, investment in storage and transport infrastructure, and the development of more climate-resistant crop varieties can potentially mitigate some of these challenges.

Dependency on Grain Imports

Africa’s reliance on grain imports is significant.In 2022, Algeria was the largest grain importer with 18.916 M tons, followed by Egypt (15.737 M tons), Morocco (8.779 M tons), Libya (3.484 M tons), and Tunisia (3.443 M tons). These import volumes highlight a substantial dependence on foreign grain supplies, due in part to insufficient domestic production to meet the demand.

Regarding the financial aspect of imports, in 2022, Egypt spent the most on grain imports, reaching a total of 6.308 billion USD. Algeria’s import value amounted to 4.606 billion USD, Morocco’s to 3.638 billion USD, Nigeria’s to 2.276 billion USD, and Tunisia’s to 1.469 billion USD.

Challenges of Import Reliance

Reliance on imports can pose multiple challenges, such as vulnerability to global market fluctuations and trade policies of exporting countries. Trade restrictions, supply chain disruptions, and logistics issues are tangible problems that can jeopardize food security in import-dependent African countries. Furthermore, currency fluctuations can significantly impact the affordability of grain imports. Additionally, reliance on a diversified set of countries for grain imports can be both a strength and a liability, as it exposes nations to varying geopolitical risks that can affect supply chains.

Conclusion

The grain industry in Africa is marked by contrasting scenarios of production capacities and import dependencies. While countries like Ethiopia and Nigeria showcase substantial production volumes, others continue to rely heavily on imports to feed their populations. The complex interplay of factors contributing to market growth and limitations underscores the need for strategic policy development aimed at enhancing self-sufficiency and mitigating the potential risks associated with import reliance. Efforts to build robust agricultural systems in Africa are essential to ensure the long-term sustainability and security of the continent’s grain supply.

Source: IndexBox Market Intelligence Platform

spacer

African grain fonio is the seed of the universe, says Senegalese chef

Fonio, a tiny grain the size of couscous, is from the millet family and considered the oldest cultivated grain in Africa. Photo by Adam Bartos.

Considered the oldest cultivated grain in Africa, fonio grows in poor soil and is drought-resistant. A member of the millet family, chef Pierre Thiam explains that the supergrain thrives in an arid environment and regenerates the soil with a short growing period of two months. It is “a nutritional powerhouse” that is gluten-free, Thiam says, and fonio is versatile, cooks quickly, and can be adapted to many types of cuisine.

He describes the tedious work his mother experienced to dehull fonio with a mortar and pestle. Eventually, a mechanization process was developed in Senegal that cleans 2 tons of fonio an hour as opposed to manually a ton a day.

Culturally significant, Thiam explains that in Mali the world for fonio is “po,”which is also the name for Sirius, the north star.“Fonio to them is the seed of the universe.”

“In an ideal world, fonio would be sourced in West Africa,” says Thiam. “The beneficiaries would be the small farms that are growing fonio. That’s their heritage grain.” With quinoa as a cautionary tale, where its cultivation extended beyond its origins in Latin America, Thiam wants to ensure that the supply is following the demand and stresses the importance of keeping that work in African hands.

Thiam is the executive chef and co-founder of Teranga in New York City and executive chef of Nok in Lagos, Nigeria. His company Yolélé advocates for smallholder farmers in the Sahelby opening new markets for crops grown in Africa. Thiam’s book is “The Fonio Cookbook: An Ancient Grain Rediscovered.”

I am leaving these recipes on this post because I find it very amusing that this SUPER FOOD so easily adapted to any quisine, in a recipe book from an AFRICAN MASTER CHEF… and this is the best they can do??? BASICALLY POURIDGE, THE POOR MANS DINNER? What a joke.

Basic Fonio

MAKES 3 TO 4 CUPS

Steaming, the most common of the traditional methods of preparing fonio, is a foolproof way to avoid overcooking the grains, but cooking it on the stovetop is an easy alternative if you don’t have a double boiler. Adding oil is optional but if you do, the grains will have a richer, fluffier texture and will keep separated.

Raw fonio can be stored for up to 2 years in a sealed container or resealable plastic bag at room temperature or in the refrigerator. Cooked fonio can be kept refrigerated in a covered plastic or glass container for 2 or 3 days.

Lalo, a powder made with dried baobab leaves, is used as a seasoning and a thickener in Senegal, although here you can also use finely chopped okra as a substitute.

Traditional Steamer Method One

Ingredients

- 1 cup raw fonio, rinsed and drained well

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 tablespoon vegetable, peanut, or olive oil

- 1 teaspoon baobab leaf powder (lalo) mixed with 1⁄4 cup water, or 2 tablespoons finely chopped okra

- 3 1⁄2 cups water plus 1⁄2 cup for sprinkling

Instructions

- Line the perforated steamer top of a double boiler with cheesecloth. Fill the bottom with 3 cups water and bring to a simmer.

- Place the fonio in the top of the double boiler, cover, and steam for about 15 minutes, until the fonio is light and fluffy.

- Remove from heat. Fold in the oil and the baobab powder mixture or the okra. Fluff the fonio with a fork and mix in the salt.

- Sprinkle the fonio evenly with the remaining 1/2 cup water, cover, and return to the heat for another 10 minutes or until the fonio grains are tender and fluffy. Fluff again with a fork and serve.

Traditional Steamer Method Two

Ingredients

- 1 cup raw fonio, rinsed and drained well

- 3 1⁄2 (about) cups water

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 tablespoon peanut, vegetable, or olive oil (optional)

Instructions

- Line a steamer basket with cheesecloth and place it in a large saucepan. Pour in about 3 cups water to fill the pan up but not touching the bottom of the basket. Bring the water to a simmer.

- Place the fonio in the basket, cover, and steam for about 15 minutes, until the fonio is light and fluffy.

- Remove from the heat and fluff with a fork. Mix the salt with the remaining 1/2 cup water and sprinkle evenly over the fonio. Cover, return to the heat, and steam until the grains are tender, another 8 to 10 minutes.

- Fluff again with a fork. Mix in the oil (if using). Serve.

Stovetop Method

Ingredients

- 2 cups water

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 cup raw fonio, rinsed and drained well

- 1 tablespoon peanut, vegetable, or olive oil (optional)

Instructions

- Combine the water and salt in a saucepan and bring to a boil. Add the fonio and stir once. Reduce the heat to a simmer and cover tightly. Cook for about 5 minutes, until the water is absorbed.

- Turn off the heat and keep the pot covered for another 2 minutes. Fluff with a fork. Mix in the oil (if using), and serve.

Fonio needs to be dehulled before cooking, a labor-intensive process that has been mechanized to accelerate production. Photo by Adam Bartos.

Noted Senegalese chef Pierre Thiam calls fonio, “a nutrition powerhouse,” that is versatile, cooks fast, and can be adapted to many types of cuisines. Photo courtesy of Yolélé.

From harvest to table, chef Pierre Thiam celebrates the African heritage crop in “The Fonio Cookbook: An Ancient Grain Rediscovered.”Photo courtesy of Lake Isle Press, Inc.

spacer

There is no denying the massive culinary impact and influence that West Africa has had across the globe. Here we’ll dig into some of the modern masterpieces of West African cuisine as well as explore some of the history that influenced its creation.

16 Nations of Deliciousness

West African cuisine combines various ingredients, recipes, and cultures from it’s 16 regional countries. Throughout centuries of history, West Africa’s interactions with outside cultures, from the Middle East to Europe, have influenced their own culinary habits and traditions, as well as the cuisines of others.

During the Conquest of Africa (the invasion, occupation, division, and colonization of Africa by European powers), colonial traders began exporting and importing ingredients from West Africa to the rest of the world. Ingredients such as black-eyed peas, rice, sorghum, millet, palm, okra, rice, and kola nuts (one of the original ingredients in Coca-Cola) were all exported from West Africa.From the Americas, yams, cassava, corn, peanuts, chili peppers, plantains, and tomatoes were imported to West Africa.

Image Credit: Flickr user Emeka B ( CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 )

During colonization, West African borders were recreated with little regard to existing territories. This forced amalgamation of African people shifted the food culture. Over that time, the region changed from having these very sharply self-identified cooking styles of individual groups to a larger West African culinary conglomerate. Unlike other colonized countries and regions, however, West Africa did not adopt the cooking styles of their colonizers. Instead, West Africans prepared these new ingredients in the way that suited their palates.

Iconic Dishes of West Africa

Now that we have identified the ingredients that were introduced to West Africa and the indigenous ingredients that came together to make up the bulk of West African cuisine, let’s explore the region’s iconic dishes.

Jollof Riceis heralded as the king of all West African meals. The basics of jollof involve rice simmered with tomato, broth, and spices (usually spicy peppers as well) with additions of meat, seafood, and vegetables. Each country has their own unique spin on this dish, with intense rivalries between neighboring countries as to whose jollof rice reigns supreme.

Thieboudienneis thought to be the grandfather of jollof rice. This is Senegal’s national dish, a one-pot wonder of rice, tomato sauce, fish, and vegetables.

Image Credit: Flickr user Samenargentine ( CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 )

FuFuis an essential food throughout West Africa. Fufu (translated to mean ‘mash or mix’)is made from boiled and mashed starches like cassava, yam, plantains, or corn (or a combination of those starchy vegetables). The mash is further pounded until it resembles bread dough. The dough is then served as a side dish for dipping, sopping, and scooping.

Image Credit: Flickr user IFPRI ( CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 )

Maafe, also known as groundnut or peanut stew, is a West African tradition. Maafe is exceptionally flavorful and savory with oodles of herbs, spices, vegetables, and braised protein (either mutton, beef, chicken, or seafood). If you would like to try a vegetarian version of maafe, check out this recipe for Creamy Peanut Stew with Black Eyed Peas and Collards.

Image Credit: Flickr user paul goyette ( CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 )

Chicken Yassais a braised chicken dish heavily seasoned with scotch bonnet peppers, garlic, onions, and ginger. Sometimes the chicken will be chargrilled before braising, to impart smoky flavor. The spicy dish can also be found made with fish and is usually served with rice.

Image Credit: Flickr user Sinsistema ( CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 )

Ewa Agoyinis a famous street food throughout West Africa. Black eyed peas are simmered soft and mashed, then topped with a spicy tomato sauce. Ewa agoyin is often served with breador fufu for dipping.

Image Credit: Flickr user secretlondon123 ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Feature Image: Flickr user spaztacular ( CC BY 2.0 )

UMM UMMM UMMM doesn’t that all look just so delicious? ARE THEY KIDDING?? Can you picture yourself eating that slop for the rest

spacer

Fonio aka Acha

The name Achan:

- Meaning: Unclear but perhaps Serpent

- Etymology: From the noun עכנא (‘achana), serpent.

spacer

Zacatlán-Ahuacatlán-Tepetzintla Nahuatl

Etymology

Borrowed from Spanish hacha, from French hache, from Frankish [Term?].

Noun acha

From Old Galician-Portugueseacha,from Old Frenchhache(“battle-axe”), from Frankish.

Noun acha – (plural achas)

- battle-axe(axe for use in battle)

spacer

Fonio (Acha)

excerpts only, you can view the full article by clicking the link above.

It is important this way to the Dogon, a people of Mali. To them, the whole universe emerged from a fonio seed—the smallest object in the Dogon experience—a sort of atomic cosmology. (Information from J. Harlan.)

It is important this way to the Dogon, a people of Mali. To them, the whole universe emerged from a fonio seed—the smallest object in the Dogon experience—a sort of atomic cosmology. (Information from J. Harlan.)

Indeed, they consider the grain exotic, and in some places they reserve it particularly for chiefs, royalty, and special occasions. It also formed part of the traditional bride price. Moreover, it is still held in such esteem that some communities continue to use it in ancestor worship. 2

Fonio is characterized by the very small size of its seeds.The tiny white grains have many uses in cooking: porridge, gruel, and couscous, for example. They are also the prime ingredient in several choice dishes for religious and traditional ceremonies. (Brent Simpson)

It is a relative of crabgrass,a European crop introduced to the United States in the 1800s as a possible food and now a much-reviled invader of lawns. However, white fonio is grown for forage in parts of the United States—apparently without causing problems.

White fonio (Digitaria exilis) is the most widely used. It can be found in farmers’ fields from Senegal to Chad.It is grown particularly on the upland plateau of central Nigeria (where it is generally known as “acha”)as well as in neighboring regions.

The other species, black fonio (Digitaria iburua), is restricted to the Jos-Bauchi Plateau of Nigeria as well as to northern regions of Togo and Benin.3 Its restricted distribution should not be taken as a measure of relative inferiority: black fonio may eventually have as much or even greater potential than its now better-known relative.

Description

As noted, there are actually two species of fonio.Both are erect, free-tillering annuals.White fonio (Digitaria exilis) is usually 30-75 cm tall. Its finger-shaped panicle has 2-5 slender racemes up to 15 cm ong. Black fonio (Digitaria iburua) is taller and may reach 1.4 m. It has 2-11 subdigitate racemes up to 13 cm long.

Although both species belong to the same genus, crossbreeding them seems unlikely to yield fertile hybrids, as they come from different parts of the same genus. 17

The grains of both species range from “extraordinarily” white to fawn yellow or purplish. Black fonio’s spikelets are reddish or dark brown. Both species are more-or-less nonshattering.

Suggested Citation:”3 Fonio (Acha).”

For a crop that is so little known to science, fonio is surprisingly widely grown. It is employed across a huge sweep of West Africa, from the Atlantic coast almost to the boundary with Central Africa.

Fonio grain is digested efficiently by cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys, and other ruminant livestock. It is a valuable feed for monogastric animals, notably pigs and poultry, because of its high methionine content.7 The straw and chaff are also fed to animals. Both make excellent fodder and are often sold in markets for this purpose. Indeed, the crop is sometimes grown solely for hay.

The straw is commonly chopped and mixed with clay for building houses or walls.It is also burned to provide heat for cooking or ash for potash

Traditionally, the grain is threshed by beating or trampling, and it is dehulled in a mortar. This is difficult and time-consuming.

Cytogenetics

As a challenge to geneticists, fonio has a special fascination. It has no obvious wild ancestor.That it appears to be a hexaploid (2n=6x=54)may help account for this. Does it, in fact, contain three diploid genomes of different origin?What are its likely ancestors, and might they be used to increase its seed size and yield?

spacer

Dogon people

Dogon men in their ceremonial attire

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,591,787 (2012–2013) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,751,965 (8.7%)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Dogon languages, Bangime, French | |

| Religion | |

| African traditional religion, Islam, Christianity | |

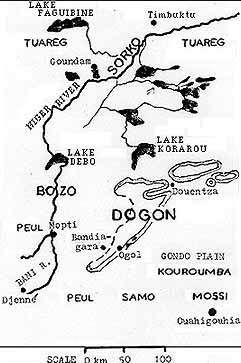

The Dogon are an ethnic group indigenous to the central plateau region of Mali, in West Africa, south of the Niger bend, near the city of Bandiagara, and in Burkina Faso. The population numbers between 400,000 and 800,000.[2] They speak the Dogon languages, which are considered to constitute an independent branch of the Niger–Congo language family, meaning that they are not closely related to any other languages.[3]

The Dogon are best known for their religious traditions, their mask dances, wooden sculpture, and their architecture. Since the twentieth century, there have been significant changes in the social organisation, material culture and beliefs of the Dogon, in part because Dogon country is one of Mali’s major tourist attractions.[4]

A Dogon hunter with a flintlock musket, 2010.

Geography and history

Dogon dwellings along the Bandiagara Escarpment.

The principal Dogon area is bisected by the Bandiagara Escarpment, a sandstone cliff of up to 500 metres (1,600 ft) high, stretching about 150 km (90 miles). To the southeast of the cliff, the sandy Séno-Gondo Plains are found, and northwest of the cliff are the Bandiagara Highlands. Historically, Dogon villages were established in the Bandiagara area a thousand years ago because the people collectively refused to convert to Islam and retreated from areas controlled by Muslims.[5]

Dogon insecurity in the face of these historical pressures caused them to locate their villages in defensible positions along the walls of the escarpment. The other factor influencing their choice of settlement location was access to water. The Niger River is nearby and in the sandstone rock, a rivulet runs at the foot of the cliff at the lowest point of the area during the wet season.

Among the Dogon, several oral traditions have been recorded as to their origin. One relates to their coming from Mande, located to the southwest of the Bandiagara escarpment near Bamako. According to this oral tradition, the first Dogon settlement was established in the extreme southwest of the escarpment at Kani-Na.[6][7] Archaeological and ethnoarchaeological studies in the Dogon region have been especially revealing about the settlement and environmental history, and about social practices and technologies in this area over several thousands of years.[8][9][10]

Over time, the Dogon moved north along the escarpment, arriving in the Sanga region in the 15th century.[11] Other oral histories place the origin of the Dogon to the west beyond the river Niger, or tell of the Dogon coming from the east. It is likely that the Dogon of today are descendants of several groups of diverse origin who migrated to escape Islamization.[12]

It is often difficult to distinguish between pre-Muslim practices and later practices. But Islamic law classified the Dogon and many other ethnicities of the region (Mossi, Gurma, Bobo, Busa and the Yoruba) as being within the non-canon dar al-harb and consequently fair game for slave raids organized by merchants.[13] As the growth of cities increased, the demand for slaves across the region of West Africa also increased. The historical pattern included the murder of indigenous males by raiders and enslavement of women and children.[14]

For almost 1000 years,[15] the Dogon people, an ancient ethnic group of Mali[16] had faced religious and ethnic persecution—through jihads by dominant Muslim communities.[15] These jihadic expeditions formed themselves to force the Dogon to abandon their traditional religious beliefs for Islam. Such jihads caused the Dogon to abandon their original villages and moved up to the cliffs of Bandiagara for better defense and to escape persecution—often building their dwellings in little nooks and crannies.[15][17]

Art

Dogon art consists primarily of sculptures. Dogon art revolves around religious values, ideals, and freedoms (Laude, 19). Dogon sculptures are not made to be seen publicly, and are commonly hidden from the public eye within the houses of families, sanctuaries, or kept with the Hogon (Laude, 20). The importance of secrecy is due to the symbolic meaning behind the pieces and the process by which they are made.

Themes found throughout Dogon sculpture consist of figures with raised arms, superimposed bearded figures, horsemen, stools with caryatids, women with children, figures covering their faces, women grinding pearl millet, women bearing vessels on their heads, donkeys bearing cups, musicians, dogs, quadruped-shaped troughs or benches, figures bending from the waist, mirror-images, aproned figures, and standing figures (Laude, 46–52).

Signs of other contacts and origins are evident in Dogon art. The Dogon people were not the first inhabitants of the cliffs of Bandiagara. Influence from Tellem art is evident in Dogon art because of its rectilinear designs (Laude, 24).

-

spacer

Culture and religion

The Dogon people with whom French anthropologists Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen worked during the 1930s and 1940s had a system of signs which ran into the thousands, including “their own systems of astronomy and calendrical measurements, methods of calculation and extensive anatomical and physiological knowledge, as well as a systematic pharmacopoeia“.[20] The religion embraced many aspects of nature which are found in other traditional African religions.

The key spiritual figures in the religion were the Nummo/Nommo twins. According to Ogotemmêli’s description of them, the Nummo, whom he also referred to as “Water”, had green skin covered in green hair, and were formed like humans from the loins up, but serpent-like below. Their eyes were red, their tongues forked, and their arms flexible and unjointed.[21]

Ogotemmêli classified the Nummo as hermaphrodites. Their images or figures appeared on the female side of the Dogon sanctuary.[22] They were primarily symbolized by the Sun, which was a female symbol in the religion. In the Dogon language, the Sun’s name (nay) had the same root as “mother” (na) and “cow” (nā).[23] They were symbolized by the colour red, a female symbol.

The problem of “twin births” versus “single births”, or androgyny versus single-sexed beings, was said to contribute to a disorder at the beginning of time. This theme was fundamental to the Dogon religion. “The jackal was alone from birth,” said Ogotemmêli, “and because of this he did more things than can be told.“[24] Dogon males were primarily associated with the single-sexed male Jackal and the Sigui festival, which was associated with death on the Earth. It was held once every sixty years and allegedly celebrated the white dwarf star, Sirius B.[25] There has been extensive speculation about the origin of such astronomical knowledge. The colour white was a symbol of males. The ritual language, “Sigi so” or “language of the Sigui”,which was taught to male dignitaries of the Society of the Masks (“awa”), was considered a poor language. It contained only about a quarter of the full vocabulary of “Dogo so”, the Dogon language. The “Sigi so” was used to tell the story of creation of the universe, of human life, and the advent of death on the Earth, during both funeral ceremonies and the rites of the “end of mourning” (“dama”).[26]

Because of the birth of the single-sexed male Jackal, who was born without a soul, all humans eventually had to be turned into single-sexed beings. This was to prevent a being like the Jackal from ever being born on Earth again. “The Nummo foresaw that the original rule of twin births was bound to disappear, and that errors might result comparable to those of the jackal, whose birth was single. Because of his solitary state, the first son of God acted as he did.“[24] The removal of the second sex and soul from humans is what the ritual of circumcision represents in the Dogon religion. “The dual soul is a danger; a man should be male, and a woman female. Circumcision and excision are once again the remedy.”[27]

The Dogon religion was centered on this loss of twinness or androgyny. Griaule describes it in this passage:

Most of the conversations with Ogotemmêli had indeed turned largely on twins and on the need for duality and the doubling of individual lives. The Eight original Ancestors were really eight pairs … But after this generation, human beings were usually born single. Dogon religion and Dogon philosophy both expressed a haunting sense of the original loss of twin-ness. The heavenly Powers themselves were dual, and in their Earthly manifestations they constantly intervened in pairs ...[28]

The birth of human twins was celebrated in the Dogon culture in Griaule’s day because it recalled the “fabulous past, when all beings came into existence in twos, symbols of the balance between humans and the divine”. According to Griaule, the celebration of twin-births was a cult that extended all over Africa.[28] Today, a significant minority of the Dogon practice Islam. Another minority practices Christianity.

Those who remain in their ethnic religion generally believe in the significance of the stars and the creator god, Amma, who created Earth and molded it into the shape of a woman,[29] imbuing it with a divine feminine principle.

If you have never seen the following post, please view it in full. It goes into great detail about pagan beliefs in “Twins” and how that plays into COVID 19 and HUNTING.

COVID 19 – PANGOLIN CONNECTION – THE ELITE and THE HUNT

also see the following post:

The Force behind the madness

space

Hogon

The Hogon is the spiritual and political leader of the village. He is elected from among the oldest men of the dominant lineage of the village.

After his election, he has to follow a six-month initiation period, during which he is not allowed to shave or wash. He wears white clothes and nobody is allowed to touch him. A virgin who has not yet had her period takes care of him, cleans his house, and prepares his meals. She returns to her home at night.

After initiation, the Hogon wears a red fez. He has an armband with a sacred pearl that symbolises his function. The Hogon has to live alone in his house. The Dogon believe the sacred snake Lébé comes during the night to clean him and to transfer wisdom.

Castes

There are two endogamous castes in Dogon society: the smiths and the leather-workers. Members of these castes are physically separate from the rest of the village and live either at the village edge or outside of it entirely. While the castes are correlated to profession, membership is determined by birth. The smiths have important ritual powers and are characteristically poor. The leather-workers engage in significant trade with other ethnic groups and accumulate wealth. Unlike norms for the rest of society, parallel-cousin marriage is allowed within castes. Caste boys do not get circumcised.[32]

Circumcision

In Dogon thought, males and females are born with both sexual components. The clitoris is considered male, while the foreskin is considered female.[24] (Originally, for the Dogon, man was endowed with a dual soul. Circumcision is believed to eliminate the superfluous one.[33]) Rites of circumcision enable each sex to assume its proper physical identity.

Boys are circumcised in age groups of three years, counting for example all boys between 9 and 12 years old. This marks the end of their youth, and they are initiated. The blacksmith performs the circumcision. Afterwards, the boys stay for a few days in a hut separated from the rest of the village people, until the wounds have healed. The circumcision is celebrated and the initiated boys go around and receive presents. They make music on a special instrument that is made of a rod of wood and calabashes that makes the sound of a rattle.

The newly circumcised youths, now considered young men, walk around naked for a month after the procedure so that their achievement in age can be admired by the tribe. This practice has been passed down for generations and is always followed, even during winter.

Once a boy is circumcised, he transitions into young adulthood and moves out of his father’s house. All of the men in his age-set live together in a duñe until they marry and have children.[34]

The Dogon are among several African ethnic groups that practice female genital mutilation, including a type I circumcision, meaning that the clitoris is removed.[35]

The village of Songho has a circumcision cave ornamented with red and white rock paintings of animals and plants. Nearby is a cave where music instruments are stored.

Dogon mask societies

The Awa is a masked dance society that holds ritual and social importance. It has a strict code of etiquette, obligations, interdicts, and a secret language (sigi sǫ). All initiated Dogon men participate in Awa, with the exception of some caste members. Women are forbidden from joining and prohibited from learning sigi sǫ. The ‘Awa’ is characterized by the intricate masks worn by members during rituals. There are two major events at which the Awa perform: the ‘sigi’ ritual and ‘dama’ funeral rituals.[36]

‘Sigi’ is a society-wide ritual to honor and recognize the first ancestors. Thought to have originated as a method to unite and keep peace among Dogon villages, the ‘sigi’ involves all members of the Dogon people. Starting in the northeastern part of Dogon territory, each village takes turns celebrating and hosting elaborate feasts, ceremonies, and festivities. During this time, new masks are carved and dedicated to their ancestors. Each village celebrates for around a year before the ‘sigi’ moves to the next village. A new ‘sigi’ is started every 60 years.

Dogon funeral rituals come in two parts. The first occurs immediately after the death of a person, and the second can occur years after the death. Due to the expense, the second traditional funeral rituals, or “damas”, are becoming very rare. Damas that are still performed today are not usually performed for their original intent, but instead are performed for tourists interested in the Dogon way of life. The Dogon use this entertainment to earn income by charging tourists money for the masks they want to see and for the ritual itself (Davis, 68).

The traditional dama consists of a masquerade intended to lead the souls of the departed to their final resting places, through a series of ritual dances and rites. Dogon damas include the use of many masks, which they wore by securing them in their teeth, and statuettes. Each Dogon village may differ in the designs of the masks used in the dama ritual. Similarly each village may have their own way of performing the dama rituals. The dama consists of an event, known as the Halic, that is held immediately after the death of a person and lasts for one day (Davis, 68).

According to Shawn R. Davis, this particular ritual incorporates the elements of the yingim and the danyim. During the yincomoli ceremony, a gourd is smashed over the deceased’s wooden bowl, hoe, and bundukamba (burial blanket). This announces the entrance of persons wearing the masks used in this ceremony, while the deceased’s entrance to his home in the family compound is decorated with ritual elements (Davis, 72–73).

The yingim and the danyim rituals each last a few days. These events are held annually to honor the elders who have died since the last Dama. The yingim consists of both the sacrifice of cows, or other valuable animals, and mock combat. Large mock battles are performed in order to help chase the spirit, known as the nyama, from the deceased’s body and village, and towards the path to the afterlife (Davis, 68).

The danyim is held a couple of months later. During the danyim, masqueraders perform dances every morning and evening for any period up to six days, depending on that village’s practice. The masqueraders dance on the rooftops of the deceased’s compound, throughout the village, and in the area of fields around the village (Davis, 68). Until the masqueraders have completed their dances, and every ritual has been performed, any misfortune can be blamed on the remaining spirits of the dead (Davis, 68).

Sects

Dogon society is composed of several different sects:

- The sect of the creator god Amma. The celebration is once a year and consists of offering boiled millet on the conical altar of Amma, colouring it white. All other sects are directed to the god Amma.[citation needed]

- Sigui is the most important ceremony of the Dogon. It takes place every 60 years and can take several years. The last one started in 1967 and ended in 1973; the next one will start in 2027. The Sigui ceremony symbolises the death of the first ancestor (not to be confused with Lébé) until the moment that humanity acquired the use of the spoken word. The Sigui is a long procession that starts and ends in the village of Youga Dogorou, and goes from one village to another during several months or years. All men wear masks and dance in long processions. The Sigui has a secret language, Sigui So, which women are not allowed to learn. The secret Society of Sigui plays a central role in the ceremony. They prepare the ceremonies a long time in advance, and they live for three months hidden outside of the villages while nobody is allowed to see them. The men from the Society of Sigui are called the Olubaru. The villagers are afraid of them, and fear is cultivated by a prohibition to go out at night, when sounds warn that the Olubaru are out. The most important mask that plays a major role in the Sigui rituals is the Great Mask, or the Mother of Masks. It is several meters long, held by hand, and not used to hide a face. This mask is newly created every 60 years.

- The Binou sect uses totems: common ones for the entire village and individual ones for totem priests. A totem animal is worshiped on a Binou altar. Totems are, for example, the buffalo for Ogol-du-Haut and the panther for Ogol-du-Bas. Normally, no one is harmed by their totem animal, even if this is a crocodile, as it is for the village of Amani (where there is a large pool of crocodiles that do not harm villagers). However, a totem animal might exceptionally harm if one has done something wrong. A worshiper is not allowed to eat his totem. For example, an individual with a buffalo as totem is not allowed to eat buffalo meat, to use leather from its skin, nor to see a buffalo die. If this happens by accident, he has to organise a purification sacrifice at the Binou altar. Boiled millet is offered, and goats and chickens are sacrificed on a Binou altar. This colours the altar white and red. Binou altars look like little houses with a door. They are bigger when the altar is for an entire village. A village altar also has the ‘cloud hook’, to catch clouds and make it rain.

- The Lébé sect worships the ancestor Lébé Serou, the first mortal human being, who, in Dogon myth, was transformed into a snake. The celebration takes place once a year and lasts for three days. The altar is a pointed conic structure on which the Hogon offers boiled millet while mentioning in his benediction eight grains plus one. Afterwards, the Hogon performs some rituals in his house, which is the home of Lébé. The last day, all the village men visit all the Binou altars and dance three times around the Lébé altar. The Hogon invites everybody who assisted to drink the millet beer.

- The twin sect: The birth of twins is a sign of good luck. The extended Dogon families have common rituals, during which they evoke all their ancestors back to their origin—the ancient pair of twins from the creation of the world.

- The Mono sect: The Mono altar is at the entry of every village. Unmarried young men celebrate the Mono sect once a year in January or February. They spend the night around the altar, singing and screaming and waving with fire torches. They hunt for mice that will be sacrificed on the altar at dawn.

Dogon villages

A typical Dogon village.

A Toguna

Villages are built along escarpments and near a source of water. On average, a village contains around 44 houses organized around the ‘ginna’, or head man’s house. Each village is composed of one main lineage (occasionally, multiple lineages make up a single village) traced through the male line. Houses are built extremely close together, many times sharing walls and floors.

Dogon villages have different buildings:

- Male granary: storage place for pearl millet and other grains. Building with a pointed roof. This building is well protected from mice. The number of filled male granaries is an indication for the size and the richness of a guinna.

- Female granary: storage place for a woman’s things, her husband has no access. Building with a pointed roof. It looks like a male granary but is less protected against mice. Here, she stores her personal belongings such as clothes, jewelry, money and some food. A woman has a degree of economic independence, and earnings and things related to her merchandise are stored in her personal granary. She can for example make cotton or pottery. The number of female granaries is an indication for the number of women living in the guinna.

- Tógu nà (a kind of case à palabres): a building only for men. They rest here much of the day throughout the heat of the dry season, discuss affairs and take important decisions in the toguna.[37] The roof of a toguna is made by 8 layers of millet stalks. It is a low building in which one cannot stand upright. This helps with avoiding violence when discussions get heated.

- Punulu (a house for menstruating women): this house is on the outside of the village. It is constructed by women and is of lower quality than the other village buildings. Women having their period are considered to be unclean and have to leave their family house to live during five days in this house. They use kitchen equipment only to be used here. They bring with them their youngest children. This house is a gathering place for women during the evening. This hut is also thought to have some sort of reproductive symbolism due to the fact that the hut can be easily seen by the men who are working the fields who know that only women who are on their period, and thus not pregnant, can be there.

spacer

![]()

![]() ROAD TO TIMBUKTU

ROAD TO TIMBUKTU

|| ROAD TO TIMBUKTU EPISODE ||

According to oral tradition, the Dogon people of south-central Mali originated near the headwaters of the Niger River, and fled their homes sometime between the 10th and 13th centuries because they refused to convert to Islam. However, the Voltaic language of the Dogon suggests a more ancient presence in their present-day homeland. They inhabit a rugged and isolated environment where cliffs protected the group from outside invaders, including French colonialists and missionaries.

According to oral tradition, the Dogon people of south-central Mali originated near the headwaters of the Niger River, and fled their homes sometime between the 10th and 13th centuries because they refused to convert to Islam. However, the Voltaic language of the Dogon suggests a more ancient presence in their present-day homeland. They inhabit a rugged and isolated environment where cliffs protected the group from outside invaders, including French colonialists and missionaries.

Traditionally, the extended patrilineal family forms the basic social unit of the Dogon, who lack strong centralized authorities. A hogon, or headman (traditionally the oldest man in the area), provides spiritual leadership and safeguards the religious masks for which the Dogon are famous; however, a council of elders holds decision-making power within each village. The Dogon maintain a kind of caste system based on occupation. Farmers rank at the top of the system, while blacksmiths and hunters, who perform “polluting” work, are lower on the caste scale.

Unlike their Muslim neighbors, most Dogon still practice a traditional religion with a complex mythology. Dogon cosmology considers every being a combination of complementary opposites; elaborate rituals are necessary to maintain the balance. Ancestor-worship is another importance facet of Dogon religion. Members of the “Society of Masks” perform rituals to guarantee that a person’s “life force” will flee from his or her corpse to a future relative of the same lineage. One of the most famous Dogon rituals is the Sigi — a series of rituals performed once every 60 years. Islamic missionaries, however, have had some success among the Dogon, and approximately 35 percent of the Dogon population are now Muslim.

Source: Microsoft Encarta Africana. ©1999 Microsoft Corporation. Used with permission.

|| ROAD TO TIMBUKTU EPISODE ||

spacer

The Kanaga mask is a mask of the Dogon of Mali traditionally used by members of the Awa Society, especially during the ceremonies of the dead (dama, ceremony of mourning). Ancestor Worship

| The Hebrew meaning of AWA

|

|

AWA av’-a `awwa’; the King James Version Ava, a’-va: A province, the people of which Shalmaneser king of Assyria placed in the cities of Samariain the room of the children of Israel taken into exile by him (2 Kings 17:24). It is probably the same as Ivva (2 Kings 18:34; 19:13; Isaiah 37:13), a province conquered by Assyria. |

What Does The Name Awa Mean?The Meaning of Names

https://www.names.org › awa › about

A user from the United Kingdom says the name Awa is of Arabic origin and means “Beautiful angel and night“

|

| The Origin of Hawaiian Awa

Pronounced “ah-vah”, which means bitter, awa it is known as the Hawaiian kava drink. Hawaiian awa has many different names, depending on the region in the Pacific Islands and the cultural background. Many know it as kava around the world. It is called yaqona in Tonga, ‘ava in Samoa, sakau in Pohnpei, and malok in Vanuatu. Hawaiians have called it awa since it first came to Hawaii thousands of years ago. Awa, in the beginning, was mostly used for religious ceremonies. Certain Gods are associated with the use of Hawaiian awa, offering blessings to crops, hunting, fishing and even unions between families. Today awa is used for medicinal reasons as well as a social and ceremonial drink. It is used to ease tension and alleviate pain. How Awa Came to HawaiiAs Pacific Islanders traveled and settled in various parts of the South Pacific, they would take their most important plants with them. This type of plant was originally known as canoe plants. Awa is extracted from the root of the piper methysticum plant, or pepper plant. During all the traveling and the years of moving through the Islands, the Hawaiian awa plant lost its ability to reproduce through seed. The Hawaiian natives found other ways to grow it. They used the stems and leaves to propagate the plant. They would mix and match different strands of awa to create different chemotypes. If they liked the effects, they kept it. If they did not like the effects, they quit growing that version. They spent much time mutating the plant until they found the most noble versions. Eventually, thirteen noble strands of Hawaiian awa were created that are of the best quality and still available today. GENETIC MODIFICATION. I find it interesting that this is a “DRINK” and “The word Nommos is derived from a Dogon word meaning to make one drink.” |

THE PHILISTINES

TYRUS-PHOENICIAN-PHILLISTINES- CANAAN-HAM-AFRICA

SIRIUS

AN-NAJM

|

|

|

|

spacer

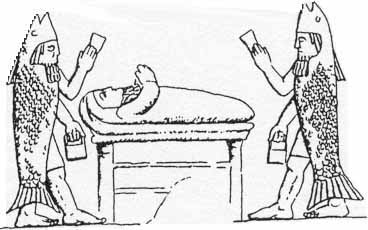

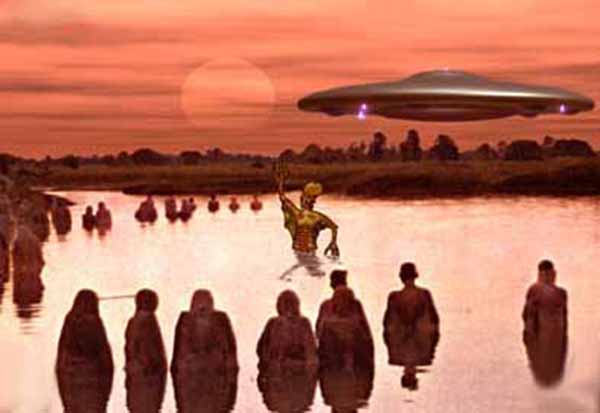

All origin stories begin with Gods who came from the sky, created humans, then left promising to return one day. They go by various names and descriptions often linked to ancient aliens. There seems to be a pattern with all of this found in oral traditions, petroglyphs, ceramics and other art forms, ancient star maps, and other artifacts. Most myths depict Gods meeting with primitive humans – their agendas varying.

The precise origin of the Dogon, like those of many other ancient cultures, is linked to the Nommo (see below). Their civilization emerged, in much the same manner as most ancient civilizations.

Because of these inexact and incomplete sources, there are a number of different versions of the Dogon’s origin myths as well as differing accounts of how they got from their ancestral homelands to the Bandiagara region. The people call themselves ‘Dogon’ or ‘Dogom’, but in the older literature they are most often called ‘Habe’, a Fulbe word meaning ‘stranger’ or ‘pagan’.

|

|

The religious beliefs of the Dogon are enormously complex and knowledge of them varies greatly within Dogon society. Dogon religion is defined primarily through the worship of the ancestors and the spirits whom they encountered as they slowly migrated from their obscure ancestral homelands to the Bandiagara cliffs. They were called the Nommo.

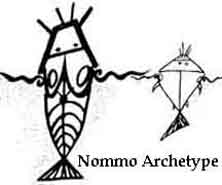

The Nommo are ancestral spirits (sometimes referred to as deities) worshipped by the Dogon people of Mali. The word Nommos is derived from a Dogon word meaning “to make one drink.” The Nommos are usually described as amphibious, hermaphroditic, fish-like creatures. Folk art depictions of the Nommos show creatures with humanoid upper torsos, legs/feet, and a fish-like lower torso and tail. The Nommos are also referred to as “Masters of the Water”, “the Monitors”, and “the Teachers”.Nommo can be a proper name of an individual, or can refer to the group of spirits as a whole.

Dogon mythology states that Nommo was the first living creature created by the sky god Amma. Shortly after his creation, Nommo underwent a transformation and multiplied into four pairs of twins. One of the twins rebelled against the universal order created by Amma. To restore order to his creation, Amma sacrificed another of the Nommo progeny, whose body was dismembered and scattered throughout the world. This dispersal of body parts is seen by the Dogon as the source for the proliferation of Binu shrines throughout the Dogons’ traditional territory; wherever a body part fell, a shrine was erected.

The Nommo allegedly descended from the sky in a vessel accompanied by fire and thunder. After arriving, the Nommos created a reservoir of water and subsequently dove into the water. The Dogon legends state that the Nommos required a watery environment in which to live. According to the myth related to Griaule and Dieterlen: “The Nommo divided his body among men to feed them; that is why it is also said that as the universe “had drunk of his body,” the Nommo also made men drink. He gave all his life principles to human beings.” The Nommo was crucified on a tree, but was resurrected and returned to his home world. Dogon legend has it that he will return in the future to revisit the Earth in a human form.

As the story goes … in the late 1930s, four Dogon priests shared their most important secret tradition with two French anthropologists, Marcel Griaule and Germain Dieterlen after they had spent an apprenticeship of fifteen years living with the tribe. These were secret myths about the star Sirius, which is 8.6 light years from the Earth.

The Dogon priests said that Sirius had a companion star that was invisible to the human eye. They also stated that the star moved in a 50-year elliptical orbit around Sirius, that it was small and incredibly heavy, and that it rotated on its axis.

Initially the anthropologists wrote it off publishing the information in an obscure anthropological journal, because they didn’t appreciate the astronomical importance of the information.

What they didn’t know was that since 1844, astronomers had suspected that Sirius A had a companion star. This was in part determined when it was observed that the path of the star wobbled.

In 1862 Alvan Clark discovered the second star making Sirius a binary star system (two stars).

In the 1920’s it was determined that Sirius B, the companion of Sirius, was a white dwarf star. White dwarfs are small, dense stars that burn dimly. The pull of its gravity causes Sirius’ wavy movement. Sirius B is smaller than planet Earth.

The Dogon name for Sirius B is Po Tolo. It means star – tolo and smallest seed– po. Seed refers to creation. In this case, perhaps human creation. By this name they describe the star’s smallness. It is, they say, the smallest thing there is. They also claim that it is ‘the heaviest star’ and is white in color. The Dogon thus attribute to Sirius B its three principal properties as a white dwarf: small, heavy, white.

spacer

MALI, WEST AFRICA

The Dogon – West African people of unique customs and mythology

National Geographic, August 2011

Reaching the edge of the Cliffs of Bandiagara is an experience words and photographs can hardly convey. After traveling two thousand kilometers through the stubbornly flat savanna of West Africa, from the Atlantic coast to the heart of Mali, reaching the cliffs is like reaching a great turning point. The cliffs stretch 200 kilometers in length and the walls plummet 200, 300, occasionally even 500 meters down. Then from the escarpment’s base, once again the desert plains spread into infinity. A few kilometers ago, we had left the road, electricity, and other comforts of civilization behind and now continue by foot up a path that takes us through a narrow canyon, steeply downhill, to the base of the cliffs where we come across a new breathtaking landscape. Leaning against the foot of the cliffs and perfectly camouflaged in the landscape, are clusters of hundreds, thousands of huts made from mud and straw. We have entered the land of the Dogon, returned to the Africa as it once was.

When visiting the land of the Dogon, the imagination is set free. The Dogon have been living along the Cliffs of Bandiagara for centuries. They are considered one of the last peoples of West Africa to still foster the old, traditional way of life. As cultivators with a rich animist culture, they are known to perform deeply symbolic rituals, dance wearing mystical masks, practice complex rituals of initiation, and tell ancient myths… It has been said and written that their knowledge of astronomy often amazes modern scientists. We have come to see for ourselves, how much of this is true.

“There is no mystery here!” our guide and interpreter Madou Kone told us at the very beginning of our trip. “Remember my words: the basic motive of the Dogon has always been just one: survival!” Madou Kone (49) is a Dogon intellectual who was born, raised, and initiated at the foot of the Bandiagara Cliffs. He had also lived in London for two years where he studied developmental strategies and earned money cooking African specialties for friends. While living in London, he sent money to his family on a regular basis. In the end he missed them so much that he returned to his home under the African sun. But then his family renounced him because he had cut off the constant flow of such wanted foreign currencies. He then worked as a consultant for environmental associations and as a leader for government projects in areas of development. Then for the past ten years, with the growth of tourism in Mali, he has dedicated himself to a much more profitable calling – that of a tour guide. Traveling through the land of the Dogon without a well-informed guide is out of the question if you don’t want to offend the locals. All of their villages and the roads connecting them are full of sacred sites and fetishes that foreigners cannot recognize when alone. Approaching these sites is prohibited, so all movement through the land of the Dogon is a serpentine journey with numerous detours. And stops. Already at the start, we became familiar with the wide spread tradition of long greetings. Each time someone would pass by us, we would all stop and then the long interrogation process would begin where the passer-by would ask Madou how he is, how his grandfather is doing, how his parents are doing, his brothers, children, how is his health, job… When the interrogator would finish, then it would be Madou’s turn to begin his interrogation. No matter what the real situation is, the answer would always be “sewo”, which means “good”. Since sewo is the word that most frequently echoes from the cliffs, the neighboring peoples have nicknamed the Dogon the “Sewo-people”.

The first thing we notice while passing the first villages underneath the cliffs are unusual structures built into the vertical rock face, often under ledges some 10-20 meters above the villages, but sometimes even at heights of 100-200 meters! These structures were built by the Tellem, who lived at the foot of the Bandiagara Cliffs before the Dogon arrived in the 14th century. The fate of the Tellem is not known: were they assimilated or were they killed by the Dogon? How they had climbed the cliffs is also not known. “The Dogon like to say that the Tellem were able to fly,” Madou laughed, “but it is more likely that they were just exceptionally great climbers!”

The Dogon reached the cliffs when fleeing from the hostile Mossi and Songhai tribes in the western part of present-day Mali. The Mossi and Songhai were known to rampage throughout western Africa, spreading Islam and enslaving weaker peoples. “Before, whenever the Dogon searched for a new place to settle, they looked for a hidden, sheltered spot, mountain, cliff, or river basin, to hide from animals and other people.” Madou explained. “The most important thing when choosing new land was the presence of water and the quality of the ground, which they determined by the growth of foliage.”

There was very little secluded land under the cliffs. So in order to use every patch of land available for growing millet, the Dogon built their first houses on rocks. When they would have to move during the dry season, they would occasionally turn to ‘supernatural’ forces to help them find water. In the village Amani we saw an unfenced pond with some thirty crocodiles in it. The villagers sacrifice some two dozen chickens daily for them. The people explained that the crocodiles had shown an inexhaustible source of water to their ancestors who had founded the village there. So, as a token of gratitude, the villagers have been revering and feeding these crocodiles ever since. They also live in peaceful coexistence with them. Children play carefree around the pond. Lambs also come to drink here, and, we are told, there have never been any attacks.

Without contacts with the outside world, the Dogon lived peacefully in the shade of the cliffs until the late 19th century when they allowed propagators of Islam to settle here. In 1930, acclaimed French anthropologist and expert for Africa, Marcel Griaule, also settled here. He studied this complex culture until his death in 1956. When peace settled in the region, the Dogon extended their fields to the non-secluded land. Griaule built them a dam and introduced new cultures, such as sorghum, onion, peanuts and other vegetables. Despite this prosperity, today the Dogon are still facing threats: global warning and desertification (the great Sahara is spreading from the north).In dry years, famine often spreads. Recently they have started raising livestock – cattle and sheep. In the past few decades they opened the gate for Islam and tourism. As a result, this archaic landscape dotted with Dogon villages also contains the occasional mosque and modest lodging for foreign visitors. However, there are still no roads, power, water supply, or signal for cell-phones.

Most tourists come here between December and February, when the climate is bearable. We are visiting the land of the Dogon in the head of April, just before the rainy season, when the air is so hot that it is impossible to sleep indoors or walk during midday.

This hellish period is also the period of festivities. The Dogon practice especially lavish animist festivities celebrating harvests or funerals. The biggest life-renewal festival, the Sigui, takes place every 60 years. The last one took place in 1967, and the next one will be in 2027. One of the goals of our two-week journey through the land of the Dogon is to find and document authentic festivities. Since a general calendar of events does not exist, we have to go from village to village and ask around.

Daily life in all the villages is the same. Women do most of the work: every morning, they take millet stored in barns with thatch roofs and spend their days grinding grains with long poles. Women also fetch water from deep wells and bring firewood from distant shrubs. They carry the loads on their heads all the way to their homes. Then, at the peak of the sweltering hot day, the women squat by the fire and cook. Men mostly sit and rest, or, at times weave straw baskets in the shade of the toguna – the central building of each village intended exclusively for men. Children with swollen bellies spend their days running and playing, and whenever they would see us, they would run up to us to beg for gifts.

“Everything is changing,” Madou complains while shooing the children away. “Before, such behavior was unacceptable. It is forbidden for children to address adults in the Dogon society. Yet they dare to demand all sorts of things from foreigners. Money has come with the tourists, and spoiled the people here. And with Islam came the concept of individualism. Before, being part of the community and being able to help others were the greatest virtues. Now all the people just think of themselves and how to reach easy money.”

One night, while sleeping in the village of Ireli, we could hear singing and banging throughout the night. In the morning, Madou told us that preparations were underway for the funeral of an influential old man that had died three months ago. When an elderly Dogon dies, the next day he is buried in one of the caves in the perforated rock face or in one of the old Tellem structures. Then the community starts gathering millet for the funeral ceremony called danyi, the purpose of which is to chase the deceased person’s soul away from the village and direct it to the afterlife. The final phase of the funeral takes place years later. Every 10 to 12 years, a dama is organized: a special ritual through which all those who have deceased since the last dama join the realm of the ancestors. After this dama, their names are not remembered any more. Instead, they are worshipped together with the whole pantheon of spirits of the ancestors.

That evening the preparations were begun for the danyi. Women spent the entire night singing and beating on millet to make beer for the festivity that would begin in eleven days. We went with Madou to visit the toguna of the deceased one’s clan where his son Amono Danjo was sitting in the company of elders. After long greetings and expressions of sorrow and condolences, Madou asked if we could return in eleven days to participate in the danyi. “That is out of the question!” Amono coldly rejected us without showing any emotions, not even for a moment. He turned his back to us as a sign that this conversation is over.

A bit caught off guard, we continued our walk from village to village, hoping to come across another festivity. We were also searching for a seri – or highly initiated elder. For the Dogon, initiation is something like education. All boys must undergo the basic stage in which they get circumcised and are introduced to the men’s world. Elders teach the newly initiated basic myths and how to run the family and use plants in the savanna.

In the old days, after circumcision, they would spend weeks in the savanna where they would find food and water themselves. Today, such groups of boys dressed in special robes choose to hang out along roads and ask passers-by for a bite. The next stage of initiation is optional, and is an introduction to the world of masks. This is when the initiates learn how to sacrifice for their ancestors, honor fetishes and dance with masks. After that, most men get married and start families. We are told that this is as far as initiation goes nowadays. In the old days, those who chose to could continue with initiation throughout their lives. Some are initiated as officials for the surroundings. Their job is to secretly survey the savannah to check if everyone respects taboos, does not harvest the wrong plants, hunt forbidden animals, or take water from protected sources. Other young men specialize as climbers. Each village has a small group of specially trained climbers that burry the dead in the high cliffs.

Those who have completed initiation are called seri. These initiates have trained all their lives and have been subjected to numerous tests. When they reach old age, they are taught the secret ritual language sigiso –the alleged cosmic language understood by all creatures. Seris used to form a special circle around the hogon – the spiritual and political authority of the Dogon village. There are several types of hogons. Sometimes the hogon is the oldest person in the village and does not necessarily have to be highly initiated. Though he is the keeper of the heritage, he makes decisions that concern the entire community only after seris have analyzed and discussed the issue. Most tribes have one hogon per village and in Arou lives the highest hogon of all the Dogon people. He was elected with the help of an omen, directly by the supreme deity, Amma.

What Does The Name Amma Mean?https://www.names.org › amma › about

User Submitted Meanings · A user from California, U.S. says the name Amma is of

African origin and means “Mother or Saturday born”. |

Amma, Ammā: 9 definitionshttps://www.wisdomlib.org › definition › amma

Oct 23, 2022 — —(EI 24), literally ‘the mother’; a village goddess. Note: amma is

defined in the “Indian epigraphical glossary” as it can be found on ancient … |

|

Etymology of amah by etymonline |

spacer

We found a 90-year-old seri in the village Ideli, in a small house at the outskirts of the village, where he lives alone. Madou explained we should not ask questions to old people, particularly not to seris and hogons. After half an hour of exchanging greetings and wishes, the seri started talking about the subject we were interested in. He said he had been right by the side of the hogon of Ideli. He used to sacrifice and choose the meat for the hogon and prepare special medicines for him. “Ever since that hogon died, I have not heard anyone speaking sigiso!” said the mysterious old man. “Islam has changed things.” We did try to ask him about myths, the spiritual life of the Dogon, and astronomy, but he kept talking about things he wanted to talk about. “You cannot ask a seri about the knowledge reserved for initiated ones only. He will never tell you that!” Madou explained.

After 15 years with the Dogon, Marcel Griaule was initiated in 1946 and seri Ogotemmeli shared some secret knowledge with him. What Griaule then published shook the scientific world. He wrote that the Dogon knew things in the universe invisible to the naked eye. They knew about Saturn’s rings, Jupiter’s satellites, the planets’ elliptical orbits… However, the central place in their mythology is reserved for Siriusand its two little followers. One is a small star barely visible by telescope and the other is a planet, still invisible to science. According to Griaule, Dogon legends tell of amphibious beings called Nommo who were sent to Earth from that planet. It makes since that the Fallen Angels are amphibious, since the heavens above are WATER. The Fallen Angels are the ones who taught mankind all the hidden knowledge they knew.

Check out the following related posts:

PREPARING US FOR THE COMING WATERWORLD

Scientists have Redefined Planets and Asteroids