You may or may not be aware that Dragons are not relegated to the Ancient Past. They are very much a part of our current society and often in the news.

Today we are going to look at some of the different ways and places were Dragons are very relevant. You may find yourself surprised at their prevalence. Dragons are a very hot topic. I don’t believe in coincidences or accidents. Everything happens for a reason. Everything has its origins in the realm of the spirit.

Our world is racing toward the time of the rise of the most evil person the world has known. The force behind his rise to power will of course be the GREAT DRAGON, the SERPENT, the DECEIVER of all of humanity.

I believe all the hype and falderal about dragons today is to prepare the way for his entrance.

spacer

If you have not seen the following related posts, check them out.

Where did the dragon myth originate, and why are dragon stories so widespread across at least two continents? Carolyne Larrington, Professor of medieval European literature at the University of Oxford, investigates.

Dragons feature in legend and folklore all across Britain, as well as Europe and Asia. They take many different forms and have varying characteristics: they can be a mild nuisance or a deadly peril; they may fly and breathe fire, or creep along spouting poison.

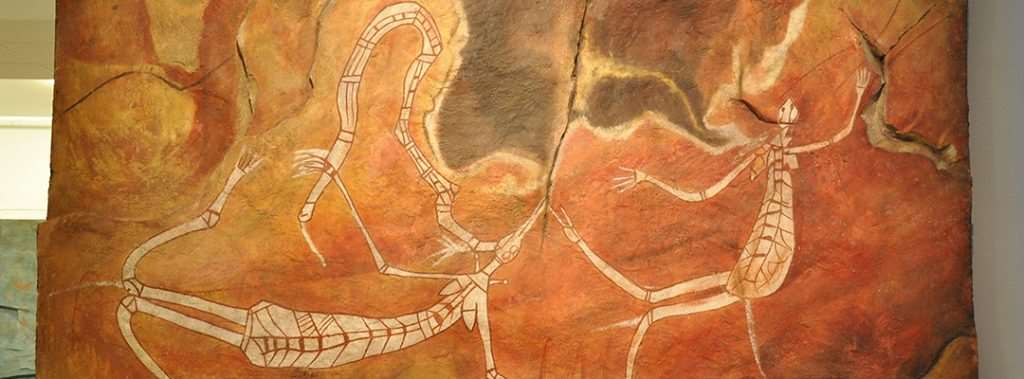

Various theories have been put forward to explain the popularity of the dragon legend. Recently it’s been suggested that the rainbow might have inspired tales of giant serpents. The Rainbow Serpent is indeed a creator-god in some Aboriginal Australian mythologies; when a rainbow appears in the sky, it’s said that the Serpent is moving between water-holes. Its capacity to find water is crucial to human survival in traditional societies, a function that connects it to the East Asian dragons. In fact, serpents are universally seen in the world’s major mythological cycles as having particular wisdom about the secrets that lie hidden beneath the earth’s surface. They can vanish into dark holes and reappear elsewhere, wriggling through the smallest chinks and crevices. Their habit of shedding their skins can signify the new knowledge they have acquired in the mysterious depths underground.

Indo-European legends, shared across Europe, the Near East and India, have a recurring story-pattern: that of the monster and the hero. In these tales, a fearsome monster, very often in serpent form, threatens human livelihoods by devouring animals and people – often young, marriageable girls. This provokes economic, political and population crises. The hero frequently needs supernatural help – a flying horse like Pegasus, or a magic sword – or he possesses superhuman strength, like the Greek hero Herakles (Hercules in Roman myth) who battled against the multi-headed Hydra in the marshes of Lerna. The monster is not always draconian in form, but it very often has serpent characteristics, perhaps dwelling in the sea, like the sea-monster that Perseus turns into stone with the aid of the Gorgon’s head when he rescued Andromeda. Or it may lurk deep within some rocky chasm like the Python, slain by the god Apollo with his arrows. This archetype symbolises the eternal battle between good and evil, but more specifically such stories are often used to explain how different peoples were able to move into new areas by conquering difficult territory and finding clever ways to overcome natural perils to make homes for themselves.

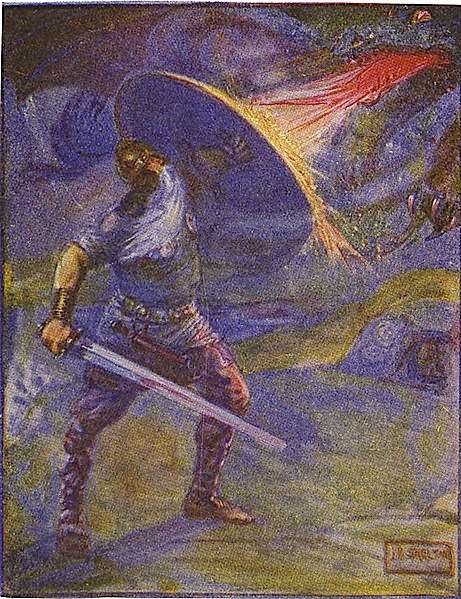

European dragons come in two kinds. The first is the northern, Germanic dragon that flies through the air on powerful wings and breathes fire when provoked. It loves gold and other kinds of treasure; where it finds a hidden hoard it moves in and sleeps on top of it. The fiery, flying dragon has been connected with the appearance of comets. The dragons that were seen flying over Northumbria in 793 (according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle) were most likely a comet of some kind, though they were interpreted at the time as presaging the ferocious attack of the Vikings on the monastery at Lindisfarne. The fire-drake is best known from literary sources, such as the Old English epic poem Beowulf, composed quite likely in the 8th century and written down in the early 11th century. This dragon found a treasure-hoard hidden in an ancient barrow and moved in. When a slave sneaked into the cave and stole a goblet, the enraged monster burned down Beowulf’s great hall and harried his people. The ageing hero went to fight the monster alone, armed with a special iron shield, but the monster seized his neck in its poisonous jaws. Beowulf’s kinsman Wiglaf hurried to help him, and together they slew the creature. Beowulf died of his injuries and had a splendid funeral. The dragon was tipped unceremoniously over a sea-cliff.

J.R.R. Tolkien drew on Beowulf when he imagined Smaug, the fiery dragon of The Hobbit, who took control of the dwarfs’ hoard. Tolkien added a detail from the most famous dragon of Old Norse legend – Fáfnir. This dragon also lies on a vast pile of treasure, one which, in the hands of the hero Sigurd who slays the monster, is later designated as the famous Rhine-gold. Fáfnir, like Tolkien’s Smaug, can also talk. The hero Sigurd fatally wounds Fáfnir, and the dying dragon warns him against treachery, communicates arcane mythological knowledge, and prophesies disaster for the hero if his counsel is not heeded.

The anthropologist David E. Jones has suggested that the dragon myth takes its origins from an innate fear of snakes, genetically encoded in humans from the time of our earliest differentiation from other primates. It is true, of course, that it makes evolutionary sense to avoid dangerous animals of every kind, but it is less clear why people should invent stories about imaginary oversized serpents in particular. Nevertheless, there is a clear benefit to tales that warn children against straying into perilous marshy areas where the serpent might seize them, or against scrambling up treacherous mountain sides in search of monsters and treasure hoards.

Some dragon tales account for geological features. The Orkneys and Shetland, along with the Faroe Islands, are the remains of the Mester Stoor Worm, a huge sea-dragon that would eat seven girls every Saturday. One day, a youth called Assipattle rowed out to meet him with some burning peat in a bucket. When the dragon swallowed up both boy and boat, the peat set fire to his liver. In his death agony he spewed out the hero, and where his teeth fell out across the North Atlantic they formed the island archipelagos. His body remains as Iceland, where his liver is still smouldering away, the cause of the island’s volcanic activity.

Medieval people may well have believed in dragons, in much the same way that they believed in lions and elephants. No one had ever seen one, but enough people knew someone who knew someone who had. Disease and miasma, which were particularly associated with marshes and fens, could be embodied as sinister, lurking creatures. Illness and its dragon-avatar could be dispelled through the power of a saint. One dragon who was terrorising the Somerset levels at Dunster was banished through the prayers of St Carantoc. Carantoc was the son of the king of Cardigan and had left Wales to lead a life as a holy man. Crossing the Severn estuary, his portable marble altar had fallen overboard. King Arthur had been trying in vain to deal with the dragon, and he enlisted Carantoc’s help after he found the altar miraculously floating on the river. Carantoc draped his priestly stole around the dragon’s neck and led him away where he could do no harm. Arthur rewarded him by building him a church at Carhampton where the marble altar was installed.

Most saints are peaceable and ill-equipped to go into battle against dragons, preferring to invoke the power of God to re-home the troublesome beast. Of course England’s national patron, St George, was a soldier-saint, courageous and fearless. George probably came from Cappadocia in Turkey. He is the patron saint of many other countries (including Georgia, named after him) and his legend recurs very widely. In English tradition his fight is said to have taken place at Dragon Hill, a low chalk tump, lying just below the Uffington White Horse in what is now South Oxfordshire. The dragon expected to eat the king’s daughter as he had devoured so many other noble girls, but George rode boldly against him and slew him with his shining sword. On Dragon Hill today you can see white spots of chalk through the turf, marking where the dragon’s poisonous blood spilled out, searing the grass.

The dragon is a strange creature then – it is monstrous, but also noble, and incorporated into many coats of arms. Indeed, the red dragon has come to symbolise Wales, after the battling dragons uncovered by Merlin. Most have been vanquished, whether by brave heroes or smart working men who figure out a technological solution to the local nuisance. Assipattle had his burning peat, More of More Hall killed the dragon of Wantley with a specially designed pointed-toe steel boot with which he delivered a fatal kick to the dragon’s tenderest portion: its bottom. But some dragons remain unfought and unrouted. There is one, apparently, that flies across the valley of the Exe in Devon from Dolbury Hill to Cadbury Castle every night, and another that lurks on his hoard under Wormelowe Barrow in Shropshire – as signalled by the monument’s name.

Although we can’t pin down the origins of these wonderful tales to any single phenomenon – dinosaur fossils, past massacres, rainbows, comets or volcanic activity – they speak to us still of the forces of nature, of greed and wickedness. And they promise that, if you’re smart and lucky, you might just win a dragon hoard of your own.

spacer

Dragon, symbol of the god Marduk, Late Assyrian Period

MeisterDrucke US

|

Dragon, symbol of the god Marduk, Late Assyrian Period, c.800-600 BC (bronze) (Drache, Symbol des Gottes Marduk, spätassyrische Zeit, ca. 800-600 v. Chr. (Bronze)) Dragon, symbol of the god Marduk, Late Assyrian Period, c.800-600 BC (bronze) by Unbekannt. Available as an art print on canvas, photo paper, watercolor board, uncoated paper or Japanese paper. Unbekannt Various dragons by different artists can be seen on this page. Click the link. |

The other horned serpent, the ušum bašmu, or ušumgallu. Unlike the previous serpent, ušumgallu is usually reserved for horned snakes with two legs (be they leonine or aquiline) and, rarely, a pair of wings. Again separating it from the bašmu is that it almost never has more than one head. Some translators use “hydra” to mean bašmu while relegating “dragon” for ušumgallu. Its name can variously be translated as “great dragon” or “prime venomous snake” or even simply “predator”. The stories told of it paint the ušumgallu as a true monster, a being of destructive force. Also unlike its many brothers, ušumgallu is usually given as a name for an individual monster, though this may not be true for all Mesopotamian traditions. When it is alone it is a monster of such great terror that gods and heroes earn their name by their defeat. Nabu, who the Babylonians considered the father of Marduk, was named “he who tramples the lion-dragon”. An Assyrian king seeking to please the god Ninurta (sometimes Nergal) placed golden ušumgallu at his statue. It was clearly not a beast that loved the gods. Even the Apkallu had to drive it away from the temple of Ishtar, lest it defile her place. The only gods associated with it were those able to kill it in battle. Mortal kings would often be represented as ušumgallu or called their name.

But, why lion-dragon? There’s already an iconographic lion dragon, but it’s never in a position as described above. Well, this may be a case of translation. Ušumgallu’s name can be split up into ušum and gallu, which you may recall was also a part of Ugallu’s name. The first part is usually agreed to be something relating to great or awesome. The second part is trickier. Some times its beast, other times enemy or adversary, and the most published is lion. (The Adversary, who goes about AS a Lion, seeking whom he may devour.) Together though, ušumgallu almost always refers to the clawed serpent emblazoned with horns. To further confuse things, ušumgallu was once the primary symbol of several gods, possibly including Marduk, before it was replaced by the more popular mušḫuššu. Then all the gods associated with mušḫuššu got stuck with ušumgallu. Mushussu may represent a transition from the two-legged ušumgallu to a more streamlined, imposing figure, combining three deadly beasts. Regardless, ušumgallu was still treated with a great deal of respect in the ancient world. Like in English, where one might refer to a tyrant as Dragon, ušumgallu was both respected and feared for its powerful undertones. Only the greatest of the great could slay such a beast.This was actually the first one of this series I drew. Which is why it’s probably better than most of them. Originally I was going to post it first, but was told that it would be better to save the dragons for last, which put him at the very back. The recreation of the depiction of usumgallu might look familiar to some as the most common figure associated with Tiamat. However, the depiction is also the closest to usumgallu, being a horned snake with the forelimbs of an eagle. I decided to make its horns rather ornate, because of its association with royalty. As well, its standing position is closer to a dinosaur than what’s represented in the art to give it a bigger, more imposing form. Well, this series has been fun! Glad to end on a high note as well, I really like the design fo- what was that. W-why do I hear boss music?

Next time, momma’s home. And she’s pissed.

spacer

Tiamat

| Tiamat | |

|---|---|

Neo-Assyrian cylinder seal impression from the eighth century BCE identified by several sources as a possible depiction of the slaying of Tiamat from the Enûma Eliš[1][2]

|

|

| Personal information | |

| Consort | Abzu; Kingu (after Abzu’s death) |

| Children | Kingu, Lahamu, Lahmu |

In Mesopotamian religion, Tiamat (Akkadian: 𒀭𒋾𒊩𒆳 DTI.AMAT or 𒀭𒌓𒌈 DTAM.TUM, Ancient Greek: Θαλάττη, romanized: Thaláttē)[3] is a primordial goddess of the sea, mating with Abzû, the god of the groundwater, to produce younger gods. She is the symbol of the chaos of primordial creation. She is referred to as a woman[4] and described as “the glistening one”.[5] It is suggested that there are two parts to the Tiamat mythos. In the first, she is a creator goddess, through a sacred marriage between different waters, peacefully creating the cosmos through successive generations. In the second Chaoskampf Tiamat is considered the monstrous embodiment of primordial chaos.[6] Some sources identify her with images of a sea serpent or dragon.[7]

In the Enûma Elish, the Babylonian epic of creation, Tiamat bears the first generation of deities; her husband, Abzu, correctly assuming that they are planning to kill him and usurp his throne, later makes war upon them and is killed. Enraged, she also wars upon her husband’s murderers, bringing forth multitudes of monsters as offspring. She is then slain by Enki‘s son, the storm-god Marduk, but not before she brings forth the monsters of the Mesopotamian pantheon, including the first dragons, whose bodies she fills with “poison instead of blood”. Marduk then integrates elements of her body into the heavens and the earth.

Etymology

Thorkild Jacobsen and Walter Burkert both argue for a connection with the Akkadian word for sea, tâmtu (𒀀𒀊𒁀), following an early form, ti’amtum.[8][9] Burkert continues by making a linguistic connection to Tethys. The later form Θαλάττη, thaláttē, which appears in the Hellenistic Babylonian writer Berossus‘ first volume of universal history, is clearly related to Greek Θάλαττα, thálatta, an Eastern variant of Θάλασσα, thalassa, ‘sea’. It is thought that the proper name ti’amat, which is the vocative or construct form, was dropped in secondary translations of the original texts because some Akkadian copyists of Enûma Elish substituted the ordinary word tāmtu (‘sea’) for Tiamat, the two names having become essentially the same due to association.[8] Tiamat also has been claimed to be cognate with the Northwest Semitic word tehom (תְּהוֹם; ‘the deeps, abyss’), in the Book of Genesis 1:2.[10]

The Babylonian epic Enûma Elish is named for its incipit: “When above” the heavens did not yet exist nor the earth below, Abzu the subterranean ocean was there, “the first, the begetter”, and Tiamat, the overground sea, “she who bore them all”; they were “mixing their waters”. It is thought that female deities are older than male ones in Mesopotamia and Tiamat may have begun as part of the cult of Nammu, a female principle of a watery creative force, with equally strong connections to the underworld, which predates the appearance of Ea-Enki.[11]

Harriet Crawford finds this “mixing of the waters” to be a natural feature of the middle Persian Gulf, where fresh waters from the Arabian aquifer mix and mingle with the salt waters of the sea.[12] This characteristic is especially true of the region of Bahrain, whose name in Arabic means “two seas”, and which is thought to be the site of Dilmun, the original site of the Sumerian creation beliefs.[13] The difference in density of salt and fresh water drives a perceptible separation.

Appearance

In the Enûma Elish her physical description includes a tail, a thigh, “lower parts” (which shake together), a belly, an udder, ribs, a neck, a head, a skull, eyes, nostrils, a mouth, and lips. She has insides (possibly “entrails”), a heart, arteries, and blood.

Tiamat is usually described as a sea serpent or dragon, although Assyriologist Alexander Heidel disagreed with this identification and argued that “dragon form can not be imputed to Tiamat with certainty”. Other scholars have disregarded Heidel’s argument: Joseph Fontenrose in particular found it unconvincing and concluded that “there is reason to believe that Tiamat was sometimes, not necessarily always, conceived as a dragoness”.[14] The Enûma Elish states that Tiamat gave birth to dragons, serpents, scorpion men, merfolk and other monsters, but does not identify her form.[15]

Mythology

Abzu (or Apsû) fathered with Tiamat the elder deities Lahmu and Lahamu (masc. the ‘hairy’), a title given to the gatekeepers at Enki’s Abzu/E’engurra-temple in Eridu. Lahmu and Lahamu, in turn, were the parents of the ‘ends’ of the heavens (Anshar, from an-šar, ‘heaven-totality/end’) and the earth (Kishar); Anshar and Kishar were considered to meet at the horizon, becoming, thereby, the parents of Anu (Heaven) and Ki (Earth).

Tiamat was the “shining” personification of the sea who roared and smote in the chaos of original creation. She and Abzu filled the cosmic abyss with the primeval waters. She is “Ummu-Hubur who formed all things”.

In the myth recorded on cuneiform tablets, the deity Enki (later Ea) believed correctly that Abzu was planning to murder the younger deities, upset with the noisy tumult they created, and so captured him and held him prisoner beneath his temple, the E-Abzu (‘temple of Abzu’). This angered Kingu, their son, who reported the event to Tiamat, whereupon she fashioned eleven monsters to battle the deities in order to avenge Abzu’s death. These were her own offspring: Bašmu (‘Venomous Snake’), Ušumgallu (‘Great Dragon’), Mušmaḫḫū (‘Exalted Serpent’), Mušḫuššu (‘Furious Snake’), Laḫmu (the ‘Hairy One’), Ugallu (the ‘Big Weather-Beast’), Uridimmu (‘Mad Lion’), Girtablullû (‘Scorpion-Man’), Umū dabrūtu (‘Violent Storms’), Kulullû (‘Fish-Man’), and Kusarikku (‘Bull-Man’).

Tiamat possessed the Tablet of Destinies and in the primordial battle she gave them to Kingu, the deity she had chosen as her lover and the leader of her host, and who was also one of her children. The terrified deities were rescued by Anu, who secured their promise to revere him as “king of the gods“. He fought Tiamat with the arrows of the winds, a net, a club, and an invincible spear. Anu was later replaced by Enlil and, in the late version that has survived after the First Dynasty of Babylon, by Marduk, the son of Ea.

And the lord stood upon Tiamat’s hinder parts,

And with his merciless club he smashed her skull.

He cut through the channels of her blood,

And he made the North wind bear it away into secret places.

Slicing Tiamat in half, he made from her ribs the vault of heaven and earth. Her weeping eyes became the sources of the Tigris and the Euphrates, her tail became the Milky Way.[16] With the approval of the elder deities, he took the Tablet of Destinies from Kingu, installing himself as the head of the Babylonian pantheon. Kingu was captured and later was slain: his red blood mixed with the red clay of the Earth would make the body of humankind, created to act as the servant of the younger Igigi deities.

The principal theme of the epic is the rightful elevation of Marduk to command over all the deities. “It has long been realized that the Marduk epic, for all its local coloring and probable elaboration by the Babylonian theologians, reflects in substance older Sumerian material,” American Assyriologist E. A. Speiser remarked in 1942[17] adding “The exact Sumerian prototype, however, has not turned up so far.” This surmise that the Babylonian version of the story is based upon a modified version of an older epic, in which Enlil, not Marduk, was the god who slew Tiamat,[18] is more recently dismissed as “distinctly improbable”.[19]

Interpretations

The Tiamat myth is one of the earliest recorded versions of the Chaoskampf, the battle between a culture hero and a chthonic or aquatic monster, serpent or dragon.[7] Chaoskampf motifs in other mythologies linked directly or indirectly to the Tiamat myth include the Hittite Illuyanka myth, and in Greek tradition Apollo‘s killing of the Python as a necessary action to take over the Delphic Oracle.[20]

In the second Chaoskampf Tiamat is considered the monstrous embodiment of primordial chaos.[6]

Robert Graves[21] considered Tiamat’s death by Marduk as evidence for his hypothesis of an ancient shift in power from a matriarchal society to a patriarchy. The theory suggests Tiamat and other ancient monster figures were depictions of former supreme deities of peaceful, woman-centered religions that turned into monsters when violent. Their defeat at the hands of a male hero corresponded to the overthrow of these matristic religions and societies by male-dominated ones. This theory is rejected by academic authors such as Lotte Motz, Cynthia Eller, and others.[22][23]

spacer

- Dragon Blood trees tower above each other in the Yemeni Island of Socotra, 27 March 2013 [KHALED FAZAA/AFP/Getty Images]

Blood Is Life — The Amazing Dragon’s Blood Tree

New research proposes classifying the threatened tree as an “umbrella species” because of its oversized ecological role.

April 9, 2020 – by John R. Platt

Dragon’s blood trees (Dracaena cinnabari) are evolutionary marvels of the plant kingdom, but they may not be around forever.

Native to a single island in the Socotra archipelago, off the coast of Yemen in the Arabian Sea, the extraordinary-looking dragon’s blood tree, which is classified as “vulnerable to extinction,” can grow to more than 30 feet in height and live for 600 years. Looming over the island’s rocky, mountainous terrain, it produces rich berries and a vermilion sap — the source of its name — that has been used for centuries as everything from medicine to lipstick, and even as a varnish for violins.

Visually, the trees are stunning. Their branches grow in an outward-forking pattern that gives them the look of a giant mushroom or an umbrella sucked inside-out by the wind.

And that appearance isn’t the only umbrella-like aspect of the dragon’s blood. New research, published in the journal Forests, suggest the tree could also be considered an umbrella species — the protection of which would benefit a wide range of other species.

The umbrella species concept has traditionally been applied to large, wide-ranging, charismatic mammals and birds such as giant pandas, mountain gorillas and northern spotted owls. The theory is that by protecting these animals and their habitats you also, directly or indirectly, conserve everything else that lives near them.

A team of researchers from Socotra, Spain and Portugal wanted to find out if the dragon’s blood tree could do the same thing — even though, unlike other umbrella species, it stays in one place. It’s not that big a leap: The tree has long been considered an indicator species, meaning it quickly shows signs of changes to its environment and plays host to a wide range of the island’s other unique wildlife. But would protecting the dragon’s blood also help other species?

The researchers studied 280 trees for two months and found that they provided food and shelter to at least 12 of Socotra’s endemic reptile species, including 10 geckos, one chameleon and a snake. Some of these species were only observed a few times, so they probably don’t fully depend on the dragon’s blood, but others, like the critically endangered gecko known only as Hemidactylus dracaenacolus, appear to only live amidst the trees.

The trees themselves weren’t the only part of the equation. Bushes from the Cissus genus grow near and around the trees, providing a shared habitat for many of the observed lizards.

Although the researchers caution that their research period was relatively short, they say this supports their hypothesis that the dragon’s blood tree should be considered an umbrella species on the Socotra archipelago and protected for the good of the whole.

And that protection is sorely needed. Dragon’s blood trees face a wide range of threats, including logging, habitat fragmentation, and overgrazing of seeds and young shoots by livestock. Few new trees survive to maturity. The trees currently occupy just 10% of their potential habitat.

For now the dragon’s blood tree persists, and its umbrella-like branches continue to serve as vital shelter and resource for the both the human and ecological communities around them.

Watch this 2014 video about the dragon’s blood tree and the threats it faces from climate change:

spacer

by A. R. Pittaway

In the 40° heat of noon – (104°F) a gentle breeze rustles the regimented stands of reeds so characteristic of the al-Hasa Oasis in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. Then, on a shrub, there is a flicker of color and a whisper of movement as a tiny but terrifying creature moves suddenly, and rays of scattered sunlight cascade from two pairs of shiny wings on a slim, bright red body, and from enormous red and blue eyes as fierce as a dragon’s in an ancient legend.

That’s not a wild simile. It is a dragon – a dragonfly – and in other times the dragonfly, Odonata, which pre-dates the dinosaur, was proportionately as dangerous as the dragon of mythology. Fossil remains from the Carboniferous period, 300 million years ago, show giants with 70-centimeter wingspans (28 inches), the largest flying insects that ever lived. Even today, in fact, the dragonfly can eat its own weight in 30 minutes.

The dragon fly is a complex creature. Almost the entire head is occupied by two enormous eyes, highly sensitive to movement and able to track prey and predators at some distance. Indeed, in some species the eyesight is so good they often fly at night; one species in Java has even become completely nocturnal.

Certain types of dragonfly – such as the Arabian Emperor (Anax parthenope) — constantly patrol a given territory in which they intercept potential victims, such as flies, and eat them on the wing, but most, like the Crimson Darter (Crocothemis servilia) and Purple-blushed Darter (Trithemis annulata) perch upon some sunny prominence whence they seize smaller insects or chase away competitors. Aerial dogfights are common, with the victor claiming the hunting ground after a noisy clash of wings.

Skilled fliers, they have four nearly equally sized wings which seem fragile but are, in fact, reinforced by a fine network of tubular veins. Unlike those of nearly all other insects, they’re attached directly to the body’s flight muscles. When the dragonfly is hovering or flying slowly forwards or backwards, each pair beats alternately to produce a characteristic rustling sound as they rub against one another. At high speed, which can exceed 80 kmh (50 mph), both pairs beat in silent unison.

In Saudi Arabia and the Arabian Gulf, the dragonfly has need of flying skills; dependent on often temporary water bodies in which to breed, many species must undertake long migrations. Each March and April, islands in the Gulf are often inundated by swarms of dragonflies on their way north, especially the Desert Darter (Selysiothemis nigra) and Arabian Emperor, many migrating during the hours of darkness.

Water plays a large part in the life cycle of the dragonfly and almost every water body has its complement of living jewels cavorting over it. Few people, admittedly, associate Arabia with water; yet there are numerous oases, waterholes and rockface trickles to be found there – which support diverse dragonfly fauna: some 22 species, ranging from the Giant Emperor dragonfly (Anaximpemtor) of Northern Oman with its 15 centimeter wingspan, to the diminutive 3 centimeter Layla Damselfly (Enallagma vansomereni) of central Saudi Arabia. Indeed, so extensive are the oases of eastern Saudi Arabia that one species, the Scarlet Darter (Crocothemis chaldaeorum), appears to have evolved in isolation there.

Some species breed in algae-overgrown channels in dark, cool oases, where, from eggs laid underwater, tiny nymphs, or naiads, are hatched. Though wingless, these nymphs have gills and are every bit as ferocious as their elders. Once mature, a nymph will crawl slowly out from the water to hang motionless on some vertical surface until gradually the back splits and a soft, pale adult emerges, its wings crumpled and small. Then, as blood is pumped into them, the wings grow and harden and it takes flight.

Considering their ferocious appearance and habits, it is not surprising that they have given rise to strange tales. In rural England – and urban New England – dragonflies were often known as “Darning Needles” or “Sewing Needles,” because, everyone thought, they were capable of sewing up the eyes, ears and mouths of children. In al-Hasa and the eastern part of Saudia Arabia, however, the tradition is mellower. In Arabic ya’sub, the dragonfly is known affectionally as Abu-Bashir, “the bearer of good news.”

A. R. Pittaway is a graduate entomologist who has spent many years working in the Arabian Peninsula.

spacer

Mukaab, A Giant Cube Building Similar to Kaaba in Riyadh

Saudi Arabia is building a giant cube in the middle of a new city center in the capital city of Riyadh.

The design of the building, which observers say is “like the Kaaba”, named The Mukaab, is the latest in a long line of buildings and cities, with a unique shape planned by the Saudi Kingdom.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) launched the project on Thursday, 16 February 2023, through his New Murabba Development Company (NMDC) or New Murabba for short.

New Murabba, the corporation headed by Crown Prince MBS, calls it “the world’s largest modern urban center in Riyadh”.

The project will feature an iconic museum, a university of technology and design, a multi-purpose immersive theater and more than 80 entertainment and cultural venues, according to a statement by the Saudi Arabian Public Investment Fund.

Mukaab, which means cube, is a gigantic structure measuring 400 meters long, wide, and high, composed of overlapping triangular shapes, in an architectural style inspired by the Najd region of Saudi Arabia.

Mukaab will be “a memorable destination and a world first experience, complete with digital and virtual technology, with the latest holography”.

The project uses the concept of sustainability, featuring green areas and walking and cycling paths that will improve the quality of life by promoting healthy and active lifestyles and community activities.

In the promotional video, CGI dragons can be seen flying around the floating structures and rocks floating in the atmosphere.

|

|

“Dining with a friendly giant. Explore fantasy worlds, or live on Mars,” says the video, blending reality with fantasy.

It looks like a computer-generated restaurant, surrounded by sea water, to fly otherworldly vehicles like a science fiction film.

The project will be located at the junction of King Salman and King Khalid roads to the Northwest of Riyadh, covering an area of 19 square kilometers, accommodating hundreds of thousands of residents.

The project will offer more than 25 million square meters of floor space, featuring more than 104,000 residential units, 9,000 hotel rooms and more than 980,000 square meters of retail space, as well as 1.4 million square meters of office space, 620,000 square meters of recreational assets and 1.8 million square meters of space dedicated to community facilities. The project is scheduled for completion in 2030.

spacer

Dragon / التنين

Alkhaimah Park (Riyadh, Ar Riyadh, Saudi Arabia)

spacer

Riyadh Season: World’s longest roller coaster launches

Sky Loop reaches a maximum height of 52 metres

Ready for a new ride? Riyadh Season zone Winter Wonderland just launched the world’s longest roller coaster, Sky Loop.

The record-breaking Riyadh roller coaster reaches a maximum height of 52 metres and a speed of 110 kilometres per hour. The track consists of crazy twists and turns called “Cobra Roll” and are named because they promise to keep you on the edge of your seat as you speed across a spiral track then plummet on a super-fast and sharp drop.

Warning: This ride is not for the faint-hearted. The controllers advise you only to step onto the roller coaster if you’re on an empty stomach. Once you’re on, you’ll be given a pair of protective glasses and then whoosh, you’re off.

spacer

Record-breaking roller coaster will travel more than 155 miles per hour

By Karla Cripps, CNN

Feb 4, 2021

A roller coaster now under development in the Middle East is set to smash existing records for speed, height and track length.

Called “Falcon’s Flight,” the ride will be the main attraction of Six Flags Qiddiya, due to open in Saudi Arabia outside of capital Riyadh in 2023.

According to a press release issued by the Qiddiya Investment Company, which has partnered with US-headquartered Six Flags to build the park, the coaster will travel across four kilometers (about 2.5 miles) of track.

Riders will experience the thrill of diving over a vertical cliff into a 160-meter-deep valley (525 feet) thanks to the use of magnetic motor acceleration (LSM technology), and “achieve unprecedented speeds of 250-plus km/h” — about 155 miles per hour.

“The Falcon’s Flight will also be the world’s tallest free-standing coaster structure, featuring a parabolic airtime hill allowing a weightlessness airtime experience,” says the release.

It will take up to 20 passengers on a three-minute long ride that and offers panoramic views of Six Flags Qiddiya. If the video rendering produced by Qiddiya is an accurate depiction of what guests will experience, this one’s only for true thrill seekers.

Appropriately, the Falcon’s Flight will be part of the City of Thrills, along with Sirocco Tower, which will be the world’s tallest drop-tower ride.

The Falcon’s Flight is being designed by Intamin. Headquartered in Liechtenstein, it’s been creating theme park attractions for over 50 years and is behind many of the world’s most famous rides.

spacer

Imagine Dragons concert at Mohammed Abdu Arena, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia on July 28, 2023

spacer

Dragon World Saudi Arabia is the third ‘Dragon City Project’ planned and developed by CHINAMEX in the Middle East, which is a commercial platform for Chinese products that combines retail and wholesale. The ‘Dragon World Saudi Arabia’ project is located in the southeast of the Saudi capital, Riyadh, adjacent to the major north-south transportation artery, the ‘East Ring Road.’ The project is located in an existing mall, Rimal Center, which covers an area of about 90,000 square meters.

Dragon World Saudi Arabia is located in the central area of the first floor of Rimal Center and will open in phases, with product categories covering textile fabrics, household goods, children products, electronic appliances, furniture and kitchenware, hardware, building materials and decoration, lighting and other categories.

Dragon World Saudi Arabia is located in the central area of the first floor of Rimal Center and will open in phases, with product categories covering textile fabrics, household goods, children products, electronic appliances, furniture and kitchenware, hardware, building materials and decoration, lighting and other categories.

The project will provide high-quality and diverse Chinese products to a population of over 8 million in Riyadh, greatly promoting economic and trade cooperation between China and Saudi Arabia.

In celebration of the hotly anticipated show premiering on August 22 in Saudi Arabia, there’ll be an immersive drone show, a screen takeover and a fireworks display in Riyadh…

Game of Thrones fans – we know you have been holding your breath since it was announced that HBO plans to do a prequel series around the Targaryen family. So, fret not, as it is nearly here.

‘House of the Dragon’ in Saudi Arabia is set to air on Monday August 22, simultaneously with the US premiere. The HBO Original drama will be available exclusively on OSN+, the region’s leading streaming service for premium entertainment, with new episodes dropping weekly on the platform.

Based on George R.R. Martin’s ‘Fire & Blood’, the ten-episode series is set 200 years before the events of Game of Thrones and tells the story of House Targaryen. If you haven’t seen all of the Games of Thrones, you can still tune in to the prequel to one of the most successful series of the past decade.

Buckle up for a 1,000-drone airborne light show

What’s more, OSN+ and HBO will be celebrating the premiere of ‘House of the Dragon’ with an immersive drone show and screen takeover that will light up the Riyadh skyline on Thursday August 18.

Fans and visitors can expect a breath-taking 1,000-drone light show above Boulevard Riyadh City, preceded by a complete screen takeover and firework display during the Gamers8 festival, the largest eSports and gaming event worldwide that’s taking place in Riyadh.

“OSN+ is excited to launch a spectacular drone show as part of the Gamers8 festival ahead of the highly anticipated release of ‘House of the Dragon’ on August 22 in the Middle East. The gaming festival will provide an engaging and immersive platform to celebrate the premiere of the first episode of the Game of Thrones prequel with fans, both within the Saudi Arabian capital and across the Kingdom”, said Ashley Rite, VP, Marketing & Growth at OSN+.

So, are you ready to get your dragon on?

OSN+ is an easily accessible online platform and is available for download across all iOS and Android devices. For SAR39 per month, with a complimentary seven-day trial, stream now and enjoy endless hours of exciting content.

Visit: OSNPlus.com

SPACER

spacer

Saudi Arabian broadcaster STV1 is to produce a local version of hit reality business format Dragon’s Den after striking a deal with distributor Sony Pictures Television.

The Middle Eastern network will begin production later this month and will air the series in the new year. The deal was inked through local production company Creative Edge International.

Sony Pictures TV claims that this is the first time that an international format has been licensed to a broadcaster in Saudi Arabia.

STV1 will initially air 26 episodes of the locally produced series, which will feature five prominent business executive including a high profile businesswoman.

The broadcaster has also acquired the UK version of the show, which currently airs on the BBC.

|

|

Dragon’s Den is a reality TV series featuring entrepreneurs pitching their business ideas in order to secure investment finance by a panel of venture capitalists. It was originated in Japan as Tiger of Money. The format was owned by Sony Pictures Television International.

It is the reality television series upon which Shark Tank is based.

International Versions

The series have been produced in numerous different countries. Aside from Japan, the show names, structures and styles are based upon the UK version

spacer

|

We are entrepreneurial creative-spirited makers of places who bring new ideas and set new standards for urban living |

Knight Dragon’s expansion plan for Middle East starts with Saudi Arabia

The company is also seeking other strategic partnerships in the Middle East, particularly in the UAE and Qatar

Knight Dragon has reported that the company is preparing to open its office in Riyadh, the Saudi capital. Knight Dragon, a leading international property developer, has scheduled launching the office in Q4 2023, as part of its expansion plan in the Middle East.

Concerning the office’s location, Knight Dragon believes that the kingdom is now a clear global leader in visionary infrastructure projects, with a solid plan to invest substantially in real estate development over the next decade.

Lee said: “The kingdom has a vibrant economy, a revitalised presence on the global stage and a younger and growing population compared with many other countries.”

He pointed out that close to 7% of Saudi Arabia’s GDP comes from real estate, making it a critical sector that underpins many others. As the Saudi economy diversifies, the goal is to double the sector’s contribution to GDP to 10% by 2030.

The Entrepreneurial Strategy

Lee explained that the company’s current strategy is exploring tokenisation, ratification of block-chain, new green construction methods using modular technology and environmental-friendly lightweight concrete.

“We are entrepreneurial, creative-spirited makers of places who bring new ideas and set new standards for modern living. Being the first company to tokenise an entire building in Central London fits exactly with our bold vision for the global property industry,” he stated.

“As Saudi Arabia continues its world-leading development and creates new global hubs, backed by plans for an exciting new airline, NEOM Airlines, Knight Dragon seeks to add value and skill where we have capability,” said Lee.

The company is also seeking other strategic partnerships in the Middle East, particularly in the UAE and Qatar.

“Core to our capability is our pioneering experience in building tokenisation, modular technology and next generation lightweight concrete technology. We are confident our experience and skill in these areas will be of great to value to Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar and the entire Middle East as the region turns vision into reality and achieves its goal of building the future,” he added.

When did you launch your Middle East operations? With the expansion in Saudi Arabia, tell us about the opportunities that you’re seeing in that market.

Knight Dragon plans to open an office in Riyadh in the last quarter of the year or the first quarter of 2024. The developer shares the same vision with Saudi Arabia and other governments across the Middle East to provide housing solutions that meet the needs and aspirations of the people, with a focus on sustainability and technology.

The real estate sector has been slower in the adoption of AI and other emerging technologies, however, the range of AI-based tools and technologies available to the industry is expanding rapidly in the Middle East.

With a vision to build large-scale projects by 2030, the real estate sector is set to accelerate economic diversification in Saudi Arabia while boosting the growth of the non-oil sector.

Saudi Arabia’s housing demand is projected to increase by over 50% to 153,000 houses by 2030. How does Knight Dragon expect to contribute to the country’s housing programme under Vision 2030?

With Knight Dragon’s vision, expertise and global experience, there is much common ground and potential for value sharing. SOURCE

spacer

- Economic relations is likely to remain at the heart of the China-Saudi relationship in the coming years, and further bilateral investment projects and energy cooperation are likely to be announced in the coming months.

- A strengthened relationship will sustain China’s energy stability and help Saudi Arabia build a more rounded, internationalist policy stance that is more independent of the US.

- China’s investment in Saudi Arabia will continue to increase, with its scope expanding beyond Beijing’s traditional focus on energy to include sectors such as construction, telecommunications, artificial intelligence and sustainable energy.

- Beijing remains likely to refrain from deep involvement in security matters in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

Key partners

China is Saudi Arabia’s largest trading partner, with USD 116.04bn in bilateral trade in 2022, a 32.9% increase from 2021. China is the world’s largest buyer of crude oil, and it buys more from Saudi Arabia than any other country. Crude oil accounted for 77% of China’s total imports from the kingdom, and this does not include China’s voluminous imports of plastic and other crude oil derivatives.

What outcomes from Xi’s visit?

Xi’s visit in late 2022 was an opportunity for Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) to show off to the kingdom’s largest trade partner how much the country had changed in the previous six years and highlight to a key stakeholder the areas of mutual benefit for the next six years and beyond. The visit concluded with at least 40 initial investment agreements worth more than SAR 110bn (USD 26.6bn) in total.

As a result of these agreements, Chinese investment into Saudi Arabia will increase beyond the traditional focus on the energy sector. Infrastructure and logistics, highlighted by China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Saudi’s Vision 2030 economic diversification plan, will receive stronger support from both governments. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia will seek to maintain a high level of engagement with Chinese firms in areas such as sustainable energy (including renewables and potentially hydrogen), telecommunications, and cyberspace and artificial intelligence (including networks and cloud services).

The trip and its agreements were a follow-up to the “comprehensive strategic partnership” agreement signed during Xi’s 2016 visit. This designation put the kingdom in one of the highest tiers of Chinese diplomatic partnerships as China seeks to secure energy supply and counter the US-led international agenda. The joint statement also highlighted the enhanced bilateral partnership in the petroleum sector. However, despite intense media attention on crude oil trading in Chinese yuan (RMB), no concrete initiatives were mentioned in the statement, and the multi-billion US dollar deals remain potential rather than guaranteed.

“It’s the economy, stupid”

A continued commitment from Saudi Arabia will be an important part to Beijing’s efforts to stabilise foreign investment amid its slowing economy and ongoing tensions with the US. Chinese official media branded a large refinery and petrochemical investment by a major Saudi Arabian oil company as “a win-win strategic move”. Beijing will continue to welcome investment from Riyadh, especially stable and long-term investment from the sovereign wealth fund.

And for all the debate about whether there is a future role for China in Saudi’s diplomatic and security interests, and a desire to see this purely through the framing of geopolitical competition between Washington DC and Beijing, the heart of this relationship is and will remain economic in the coming years.

What Riyadh wants and needs

To be able to build the components of the Vision 2030 economic diversification plan, the kingdom needs foreign direct investment, (oil) revenue, workers and materials. All of these things China can provide: Chinese construction companies will usurp US firms from their historical role as external construction and development partners in Saudi Arabia; Chinese-owned infrastructure will be put into the new “smart cities” systems that are a cornerstone of the futuristic elements of multiple giga-projects; and Chinese joint investment will drive more manufacturing, from electric vehicles to building construction materials. All of which will provide China with overseas investment opportunities while Beijing also expands its global influence.

spacer

spacer

Dragons in the Bible: What does the Bible say … – Yahoo Sports

And there appeared a great wonder in heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars: And she being with child cried, travailing in birth, and pained to be delivered. And there appeared another wonder in heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads. …

spacer

-

Their wine is the poison of dragons, and the cruel venom of asps.

-

And I went out by night by the gate of the valley, even before the dragon well, and to the dung port, and viewed the walls of Jerusalem, which were broken down, and the gates thereof were consumed with fire.

-

I am a brother to dragons, and a companion to owls.

-

Though thou hast sore broken us in the place of dragons, and covered us with the shadow of death.

-

Thou didst divide the sea by thy strength: thou brakest the heads of the dragons in the waters.

-

Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet.

-

Praise the Lord from the earth, ye dragons, and all deeps:

-

And the wild beasts of the islands shall cry in their desolate houses, and dragons in their pleasant palaces: and her time is near to come, and her days shall not be prolonged.

-

In that day the Lord with his sore and great and strong sword shall punish leviathan the piercing serpent, even leviathan that crooked serpent; and he shall slay the dragon that is in the sea.

-

And thorns shall come up in her palaces, nettles and brambles in the fortresses thereof: and it shall be an habitation of dragons, and a court for owls.

-

And the parched ground shall become a pool, and the thirsty land springs of water: in the habitation of dragons, where each lay, shall be grass with reeds and rushes.

-

The beast of the field shall honour me, the dragons and the owls: because I give waters in the wilderness, and rivers in the desert, to give drink to my people, my chosen.

-

Awake, awake, put on strength, O arm of the Lord; awake, as in the ancient days, in the generations of old. Art thou not it that hath cut Rahab, and wounded the dragon?

-

And I will make Jerusalem heaps, and a den of dragons; and I will make the cities of Judah desolate, without an inhabitant.

-

Behold, the noise of the bruit is come, and a great commotion out of the north country, to make the cities of Judah desolate, and a den of dragons.

-

And the wild asses did stand in the high places, they snuffed up the wind like dragons; their eyes did fail, because there was no grass.

-

And Hazor shall be a dwelling for dragons, and a desolation for ever: there shall no man abide there, nor any son of man dwell in it.

-

Nebuchadrezzar the king of Babylon hath devoured me, he hath crushed me, he hath made me an empty vessel, he hath swallowed me up like a dragon, he hath filled his belly with my delicates, he hath cast me out.

-

And Babylon shall become heaps, a dwellingplace for dragons, an astonishment, and an hissing, without an inhabitant.

-

Speak, and say, Thus saith the Lord God; Behold, I am against thee, Pharaoh king of Egypt, the great dragon that lieth in the midst of his rivers, which hath said, My river is mine own, and I have made it for myself.

-

Therefore I will wail and howl, I will go stripped and naked: I will make a wailing like the dragons, and mourning as the owls.

-

And I hated Esau, and laid his mountains and his heritage waste for the dragons of the wilderness.

-

And there appeared another wonder in heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads.

-

And his tail drew the third part of the stars of heaven, and did cast them to the earth: and the dragon stood before the woman which was ready to be delivered, for to devour her child as soon as it was born.

-

And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels,

spacer

Analysis

Analysis