From the photo above, you can probably guess that what lead me to this subject was a link to JANUS which was the topic of another article I was working on this week. I have to tell you, the more I research, the more I find that EVERYTHING all ties together. Every topic I pick up leads me in an endless string of related topics and they all lead back to the beginning. Literally, the beginning. The fall of man in the Garden of Eden. From that day forward there has been a war between the forces of GOOD and EVIL.

Things get very complicated when trying to present the TRUTH to the World. Because the further that mankind got from the Garden of Eden, the more the TRUTH was covered up, forgotten and perverted. So that Pagans had no real understanding of the TRUTH. They only know what they were told to be true, much like the world today. The ancient people did have first hand knowledge of SPIRITS. Something that modern society was lacking. We are catching some of it today. As neo-paganism grows, people are seeking out SPIRITS and calling them IN. We are seeing the fruit of that unfortunately, in the state of the world. I hate to tell you, things are about to get much worse.

The world has forgotten what it was like to be at the mercy of EVIL SPIRITS. The TRUE PAGAN WORLD knew all to well. They were fully aware that their survival depended upon their ability to appease and please the ruling spirits. The ancient people were at their mercy. The world today has been living under grace. God has been keeping these spirits at bay to allow time for all who were willing to come to him by choice, to come.

Sadly, time is up. The door of grace is closing, the veil is lifting and gates are opening. Demonic entities are being invited in to our realm and they do not hesitate to accept the invitation. So far they have been trickling in. But, there has been some outrageously powerful magic spells going forth, and the watered down postmodern world has not got the spiritual wherewithal to stand against the forces of darkness that are about to come in like a flood!

The smartest thing the devil ever did was convince the world he does not exist…or worse yet that he is the real Benevolent Creator. People generally believe one or the other. Either they think all things spiritual are ridiculously ignorant and foolish, OR they believe that LUCIFER is the LIGHT an the TRUTH and the WAY they want to go.

In my writing it is my desire to enlighten people to the truth, and show how we have been allowing the demonic forces to lure us into activities, thought patterns, behaviors and beliefs that are taking us down to the PIT of HELL and bringing in the very ENTITIES that will bring about our final extinction.

I am aware that this post if very lengthy. That is because it contains a wealth of information that is vital to your understanding of what is happening in these days we are living. Hang in with me and review the entire post to the end. I am seriously endeavoring to bring the light of the TRUTH and help you understand the battle in which you find yourself.

Let’s take a look at MariGras/Carnival/Masquerade. All in GOOD FUN…Right?

RELATED POST:

THE JANUS KEY

Krewe – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A krewe (pronounced “crew”) is a social organization that puts on a parade or ball for the Carnival season. The term is best known for its association with Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans, but is also used in other Carnival celebrations around the Gulf of Mexico, such as the Gasparilla Pirate Festival in Tampa, Florida, Springtime Tallahassee, and Krewe of Amalee in DeLand, Fl with the Mardi Gras on Mainstreet Parade as well as in La Crosse, Wisconsin[1] and at the Saint Paul Winter Carnival.

The word is thought to have been coined in the early 19th century by an organization calling themselves Ye Mistick Krewe of Comus,[2] as an archaic affectation; with time it became the most common term for a New Orleans Carnival organization. The Mistick Krewe of Comus itself was inspired by the Cowbellion de Rakin Society that dated from 1830, a mystic society that organizes annual parades in Mobile, Alabama.[3]

I wanted to find a video that would demonstrate the real debauchery that is the Mardi Gras Celebration. All the videos I could find that looked like they might paint a true picture were rated (R) Restricted to Mature Audiences or X – Pornography. That is the real picture of Mardi Gras. People half naked or fully naked, sex in the street, drunken, stoned, high, out of their minds, worked into a ecstatic frenzy by the noise, the smells, the sounds, the lights and the energy of the event. Finally, driven to unspeakable acts by the spirits that have been welcomed to the party.

carnal – kahr-nl – adjective

- pertaining to or characterized by the flesh or the body, its passions and appetites; sensual: carnal pleasures.

- not spiritual; merely human; temporal; worldly: a man of secular, rather carnal, leanings.

RESOURCE LIBRARY | ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Carnivore

A carnivore is an organism that eats mostly meat, or the flesh of animals. Sometimes carnivores are called predators.

carnival (n.)

![]()

What the Bible says about Carnal Nature

(From Forerunner Commentary)

Genesis 1:26-31

In the beginning, Adam and Eve were not created with the evil nature we see displayed in all of mankind. At the end of the sixth day of creation, God took pleasure in all He had made and pronounced it “very good,” including Adam and Eve and the nature or the heart He placed in them. An evil heart cannot possibly be termed “very good.” They were a blank slate, one might say, with a slight pull toward the self, but not with the strong, self-centered, touchy, and offensive heart that is communicated through contact with the world following birth.

Following Adam and Eve’s creation, God placed them in Eden and instructed them on their responsibilities. He then purposefully allowed them to be exposed to and tested by Satan, who most definitely had a different set of beliefs, attitudes, purposes, and character than God. Without interference from God, they freely made the choice to subject themselves to the evil influence of that malevolent spirit. That event initiated the corruption of man’s heart. Perhaps nowhere in all of Scripture is there a clearer example of the truth of I Corinthians 15:33: “Evil communications corrupt good manners.“

Comparing our contact with Satan to Adam and Eve’s, a sobering aspect is that God shows they were fully aware of Satan when he communicated with them. However, we realize that a spirit being can communicate with a human by transferring thoughts, and the person might never know it! He would assume the thoughts were completely generated within himself. (So, people think that they are acting to fulfill their own desires, when in reality they can be acting to fulfill the desires of the spirits that are influencing and/or controlling them.)

Following their encounter with the evil one, “the eyes of both of them were opened, and they knew that they were naked” (Genesis 3:7). This indicates an immediate change in their attitudes and perspectives. It also implies a change of character from the way God had created them, as they had indeed willingly sinned, thus reinforcing the whole, degenerative process.

This began not only their personal corruption but also this present, evil world, as Paul calls it in Galatians 1:4. All it took was one contact with, communication from, and submission to that very evil source to effect a profound change from what they had been. The process did not stop with them, as Romans 5:12 confirms, “Therefore, just as through one man sin entered the world, and death through sin, and thus death spread to all men, because all sinned.” Adam and Eve passed on the corrupt products of their encounter with Satan to their children, and each of us, in turn, has sinned as willingly as our first ancestors did.

When we are born, innocent of any sin of our own, we enter into a 6,000-year-old, ready-made world that is permeated with the spirit of Satan and his demons, as well as with the evil cultures they generated through a thoroughly deceived mankind. In consequence, unbeknownst to us, we face a double-barreled challenge to our innocence: from demons as well as from this world.

Six thousand years of human history exhibit that we very quickly absorb the course of the world around us and lose our innocence, becoming self-centered and deceived like everybody else (Revelation 12:9). The vast majority in this world is utterly unaware that they are in bondage to Satan – so unaware that most would scoff if told so. Even if informed through the preaching of the gospel, they do not fully grasp either the extent or the importance of these factors unless God draws them by opening their eyes spiritually (John 6:44-45).

John W. Ritenbaugh

Communication and Leaving Babylon (Part Three)

spacer

Mardi Gras: Mystery and History

From the moment visitors enter the Presbytere, they are surrounded by the madcap merriment of Mardi Gras. Watching mischievously over the entry foyer is a pair of jesters, perched atop an elaborate sculpture of symbols associated with Carnival. In the adjacent introductory gallery, “mystery objects” fade in and out of view, harbingers of marvelous revelations to come.

Built upon a European foundation, Mardi Gras is a multicultural festival that also reflects Louisiana’s African and Caribbean connections. Although Carnival’s modern roots can be traced to twelfth-century Rome, it is believed that the medieval pre-Lenten celebration descended from the fertility rituals and seasonal events associated with earlier cultures. The exhibition compares ancient practices – animal sacrifice, masquerade, feasting – to contemporary traditions such as the boeuf gras (fatted calf), masking and spirited Courir practiced in rural Louisiana.

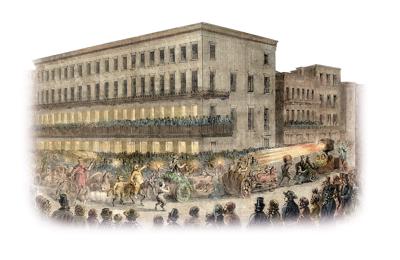

Although there is scant evidence of Carnival during the early 1700s, by 1781 it was established enough for Spanish colonial authorities to forbid free people of color and slaves to mask or mimic whites during the Carnival season. By the late nineteenth century, however, public masquerade balls and street processionals had evolved into a complex structure of social activities. These changes occurred as a result of public outcry over the prevalence of disorderly conduct during the antebellum era. In 1857 a new organization, the Mistick Krewe of Comus, emerged to transform the holiday. Costumed as “The Demon Actors in Milton’s Paradise Lost” Comus members presented a dignified nighttime street procession followed by a private ball at the Gaiety Theatre. The aura of mystery and surprise associated with krewes to this day was conceived by Comus, which is represented in the exhibition by several extremely rare artifacts including a feathered duck helmet from 1908 and a parure (set of jewelry) from 1893.

Within fifteen years two more krewes – Twelfth Night Revelers and Rex – were born. The latter organization, which achieved prominence by billing its monarchs as the king and queen of Carnival, established a precedent by introducing a daytime parade. A huge display containing costumes and jewelry from the late 1800s shows the splendor and imagination of the first Rex celebrations.

Within fifteen years two more krewes – Twelfth Night Revelers and Rex – were born. The latter organization, which achieved prominence by billing its monarchs as the king and queen of Carnival, established a precedent by introducing a daytime parade. A huge display containing costumes and jewelry from the late 1800s shows the splendor and imagination of the first Rex celebrations.

spacer

A person walks among beads during a parade on Feb. 17, 2017, in New Orleans. The Washington Post / Getty Images

In the Christian calendar, Fat Tuesday or Shrove Tuesday, the day before the start of Lent on Ash Wednesday, is a day to feast before the weeks-long fast that ends with Easter. While it’s many cities celebrate that last chance to party, which falls this Tuesday, no city is more famous for Mardi Gras — “Fat Tuesday” in French — than New Orleans.

And, though the Mardi Gras festivities in New Orleans originated in this Christian tradition, today the celebration is better known as a day for people of all faiths, races, and ethnicities to come together at the parades, eat great food, and compete to catch beads, doubloons and other throws from the people wearing masks on the floats parading down the streets.

Here’s an introduction to the history behind some of those popular traditions.

Krewes

This term for the New Orleans clubs that organize the Mardi Gras festivities was coined by The Mystick Krewe of Comus, the group that put on the first parade in the city with themed floats — the model for future parades — in 1857. They started the tradition of wearing masks and carrying torches, known as flambeaux, to light the evening revelries. The organizers came from Mobile, Ala.,

Mobile, Alabama – First Capital of Colonial French Louisiana

“On January 20, 1702, French colonists, led by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, establish Fort Louis de la Mobile on a bluff twenty-seven miles up the Mobile River from Mobile Bay. The settlement, soon known simply as “Mobile,” moved to its permanent site at the mouth of the Mobile River in 1711. It served as the capital of the colony of Louisiana from its founding to 1718.” (Alabama Department of Archives and History)

which had been hosting similar festivities ever since French-Canadian explorer Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville threw a party when he landed in the Gulf Coast city (which he called Point du Mardi Gras) on Fat Tuesday in 1699.

Though the krewes’ public parades meant the festivities could be seen by the general public, that didn’t mean anybody could participate in the clubs or attend the balls they held. Membership to five of the earliest clubs — Comus, Momus, Twelfth Night, Rex and Proteus — had been mostly closed to all but the moneyed elites. Not coincidentally, the number of these groups ballooned in the first half of the 20th century, as the populations left out formed their own: Italians, Germans, the Irish, women. African-Americans formed Zulu, the krewe famous for starting the tradition of handing coconuts in 1910 because they were less expensive than beads.

Mardi Gras Colors

The Rex Organization — the group founded in 1872 that’s also famous for starting the tradition of naming a parading Carnival King — claims credit for the purple, green and gold color scheme now associated with Mardi Grass. That was the color-scheme of their 1892 “Symbolism of Colors” parade, and the three shades are said to symbolize justice, faith and power, respectively.

Masks and Costumes

Masks and costumes have been associated with Shrove Tuesday celebrations for centuries. And even today of the masks commonly seen in New Orleans on Mardi Gras are the same types popularized by the two-to-three-week-long Carnivale in Venice that culminates with Fat Tuesday. But masking and costume-wearing in New Orleans also has a specifically American history, as it was another way for revelers who were officially excluded from the festivities to join in, by concealing their identities.

This phenomenon was particularly pronounced during the Jim Crow era of the early 20th century. For example, the African-American men now known as Mardi Gras Indians first paraded down the city’s back streets in Native American costumes, in a nod to Native Americans who took in and protected runaway slaves. Another poignant example, according to Kim Marie Vaz’s The ‘Baby Dolls‘: Breaking the Race and Gender Barriers of the New Orleans Mardi Gras Tradition, can be found in the African-American prostitutes who dressed up as “Baby Dolls” — a persona chosen because that’s what male clients called them — in hopes that the costumes would help them land work at a time when sex work was racially restricted.

These days, the Mardi Gras tradition has earned a special exemption from the Louisiana law that generally bans concealing or disguising one’s face in public.

Float riders toss beads, cups and doubloons to fans and revelers in the 2013 Krewe of Bacchus Mardi Gras Parade on Feb. 10, 2013, in New Orleans

Float riders toss beads, cups and doubloons to fans and revelers in the 2013 Krewe of Bacchus Mardi Gras Parade on Feb. 10, 2013, in New Orleans

Beads and Throws

The throwing of beads and fake jewels, from parade floats to those watching down below, is thought to have started in the late 19th century, when a carnival king threw fake strands of gems and rings to his “loyal subjects” sometime in the 1890s. By the early 1920s, one of the Krewes, probably Rex, started regularly throwing strands of glass Czech beads, a precursor to the plastic beads seen today.

Other “throws” — such as “doubloons” marked with the names of the krewes that make them — followed after.

Recently, during a clean-up project, New Orleans excavated more than 45 tons of beads from its storm drains.

King Cakes

Likely one of the many Carnival traditions brought over by the French settlers who landed in North America, this cake with a baby Jesus figurine baked inside is a symbol of the Epiphany, the day when the three Kings brought gifts to the baby Jesus.

The round cake, which nowadays comes decked out in green, gold and purple icing, dates back to the Middle Ages when European Christians feasted before the Lenten fast. Like many Christian folk traditions, it may originally have had pagan origins. During Saturnalia, the ancient Roman winter solstice celebration of the deity Saturn, the person who found a special item hidden in a cake would be “king of the day,” according to the Larousse Gastronomique culinary encyclopedia.

But, as NPR has reported, the precise reason behind the tiny baby figure in the cake may be a little bit more down-to-earth: it was a surplus supply of French porcelain dollhouse figures, chanced upon by a New Orleans baker in the 1940s, that first gave the cake that local spin.

spacer

The Story Behind Cajun Mardi Gras Masks

Wherever Mardi Gras is celebrated, the mask is key. Behind the best masks, they can’t tell whether you are laughing or crying. They can’t tell how absolutely drunk you are. The mask helps erase consequence. “Riders want folks to say, ‘Well, I didn’t see you on Mardi Gras!,’” claims Iota Louisiana mask-maker Jackie Miller. “Then they can say, ‘Oh, yes, you did; you just didn’t recognize me.’”

In South Louisiana, myriad small communities celebrate French-inspired Courir de Mardi Gras, or Fat Tuesday Runs through their towns. On horseback, flatbed trucks and ATVs, hordes of colorfully garbed riders blaze through the middle of big, Cajun crowds while singing, shouting and begging for nickels, trinkets and ingredients for a gumbo meal to be shared by the community later that night. The runs’ overlords (the capitaines) wear traditional wild, flashy robes and pointed hats called capuchin, while barking instructions to their foolish riders. The capitaines leave their faces exposed to let everyone know who is in charge. The drunken, debauched riders, however, hide their human identities behind various parish-specific masks made and molded out of wire mesh.

The wire masks of Church Point, for instance, are known to be plain, featuring regular human noses. Their capuchin are not as tall. Basile’s masks have no nose, just simple, colorful stylized features painted directly onto the screen.

Unlike other mask-makers, Lou Trahan covers her masks with colored felt, yarn, buttons, lace and other knickknacks. For 20 years, Trahan has been one of two people making traditional wire masks for the Egan community southwest-ish of Iota, between Crowley and Jennings. Egan happily stands in the shadow of the much larger Tee Mamou parade just to the west. She began making masks for her husband and two boys to wear while running with Mermentau. Of course, admiring friends soon wanted their own masks, which Trahan obligingly made.

Mermentau from the French word mer, which means “sea”.[4]

The Mermentau area was once reputedly a refuge for smugglers. It was a crossing point for brave travelers on the Old Spanish Trail, but had such a bad reputation that until the Louisiana Purchase no one would go there to see how many people there were.

John Landreth was a surveyor who was sent from Washington, D.C., in 1818 to look for timber in Acadiana that could be harvested for the use of building Navy ships. He kept a journal and had this to say: “…these places, particularly the Mermentau and Calcasieu are the harbours and Dens of the most abandoned wretches of the human race… smugglers and Pirates who go about the coast of the Gulph (sic) of vessels of a small draught of water and rob and plunder without distinction every vessel of every nation they meet and are able to conquer and put to death every soul they find on board without respect of persons age or sex and then their unlawful plunder they carry all through the country and sell at a very low rate and find plenty of purchasers.” [5]

spacer

English word mask comes from Proto-Indo-European *mozgʷ-, Proto-Indo-European *meyǵ-, Proto-Indo-European *moiḱ-sḱ-o/eh₂-, and later Proto-Germanic *maskwǭ (Loop, knot. Mesh used as a filter, facemask. Mesh, netting.).

Mask detailed word origin explanation

| DICTIONARY ENTRY | LANGUAGE | DEFINITION |

|---|---|---|

| *mozgʷ- | Proto-Indo-European (ine-pro) | |

| *meyǵ- | Proto-Indo-European (ine-pro) | |

| *moiḱ-sḱ-o/eh₂- | Proto-Indo-European (ine-pro) | |

| *mozgo- | Proto-Indo-European (ine-pro) | netting, mesh, knot, loop |

| *maihskaz | Proto-Germanic (gem-pro) | |

| *maskwǭ | Proto-Germanic (gem-pro) | Loop, knot. Mesh used as a filter, facemask. Mesh, netting. |

| mæscre | Old English (ca. 450-1100) (ang) | Mesh. Spot, blemish. |

| *maiskaz | Proto-Germanic (gem-pro) | A mash. Mixture. |

| mǣsc- | Old English (ca. 450-1100) (ang) | |

| *masc | Old English (ca. 450-1100) (ang) | |

| maske | Middle English (1100-1500) (enm) | |

| mask | English (eng) | (UK, _, dialectal, Scotland) The mesh of a net; a net; net-bag.. A mesh. |

masquerade wikipedia

WOTD – 9 October 2020

Etymology

The noun is borrowed from Middle French mascarade, masquarade, masquerade (modern French mascarade (“masquerade, masque; farce”)), and its etymon Italian mascherata (“masquerade”), from maschera (“mask”) + -ata. Maschera is derived from Medieval Latin masca (“mask”): see further there. The English word is cognate with Late Latin masquarata, Portuguese mascarada, Spanish mascarada.[1]

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY NEWSROOM

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY NEWSROOM

Inside New Orleans’ Vampires and Voodoo

Voodoo As a New Orleanian, I often forget about Voodoo — until I am reminded by businesses with Voodoo in the title or dolls in French Quarter gift shops. It all seems so commercialized … And that’s because those who do practice Voodoo keep it a secret. During a recent conversation, one of our team members, Jake…

|

|

August 3, 2012

Voodoo

As a New Orleanian, I often forget about Voodoo — until I am reminded by businesses with Voodoo in the title or dolls in French Quarter gift shops. It all seems so commercialized …

And that’s because those who do practice Voodoo keep it a secret.

During a recent conversation, one of our team members, Jake Clapp, explained that there are indeed people who practice Voodoo in New Orleans (Jake wrote a piece on the topic last year for Baton Rouge daily newspaper The Advocate). He said there are two types of Voodoo that independently grew out of African and Catholic customs, New Orleans Voodoo and Haitian Voodoo.

New Orleans Voodoo developed when Catholic plantation owners forced slaves to exercise their faith. While slaves embraced Catholicism, they held on to African religious traditions — using herbs, poisons and charms. These practices are seen as good luck and connections to a spiritual world, not unlike the customs of other religious sects.

Then there is false interpretations of Voodoo that link them to satanic rituals or magic. The rise in films and stereotypes negatively portraying Voodoo in the mid-20th century is what caused practitioners to keep their beliefs close to the vest.

|

|

Vampires

When I was about 13 or so, I remember walking through the French Quarter one night after dinner with my family. On this stroll, we passed a man with red contacts wearing a top hat. My parents told me matter-of-factly that the man was a vampire. I had always heard of New Orleans vampires, but this was the first evidence of it I saw first hand.

As I grew older, and started to go downtown with friends, I began to notice businesses that were frequented by people identifying themselves as vampires or that hung vampire art (with vampire either as the subject or the artist).

Jake Clapp also wrote a piece for the Times Picayune about New Orleans vampirism. He explained that people gravitate toward vampire culture for several reasons: religion, being part of group, enjoying the mysticism, or simply for the fashion. His story focused on a French Quarter fangsmith who crafts pointed dentures for both vampire fans and vampires themselves.

The storeowner explained that his clientele had dropped since Hurricane Katrina, when a lot of the New Orleans vampire community left the city. However, the rise in vampire pop-culture from “Twilight” and “True Blood” has brought business back to some vampire shops.

Most vampire devotees seem to focus mostly on demeanor and costume, while only a minority take it to the extreme, drinking blood or eating raw meat. Overall, they are similar to other enthusiasts, taking bit of tradition and giving it new life in the modern world, and adding to New Orleans’ multi-layered cultural landscape.

spacer

What is Mardi Gras?

The terms “Mardi Gras” (mär`dē grä) and “Mardi Gras season“, in English, refer to events of the Carnival celebrations, ending on the day before Ash Wednesday. From the French term “Mardi Gras” (literally “Fat Tuesday”), the term has come to mean the whole period of activity related to those events, beyond just the single day, often called Mardi Gras Day or Fat Tuesday. The season can be designated by the year, as in “Mardi Gras 2008”.

The time period varies from city to city, as some traditions consider Mardi Gras as the Carnival period between Epiphany or Twelfth Night and Ash Wednesday. Others treat the final three-day period as being Mardi Gras. In Mobile, Alabama, Mardi Gras events begin in November, followed by mystic society balls on Thanksgiving, then New Year’s Eve, formerly with parades on New Year’s Day, followed by parades and balls in January & February, celebrating up to midnight before Ash Wednesday.

Other cities most famous for their Mardi Gras celebrations include Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, andNew Orleans, Louisiana. Many other places have important Mardi Gras celebrations as well.

|

|

|

Harlequin legacy for the Mardi Gras is not Harlequin as a pattern for the costumes used for the carnival, but rather to the Harlequin’s costumes, especially his famous mask. However, the mask is no longer in the original shape as in the Commedia dell’Arte, but it has been modified and adjusted with today’s culture.

The dark side of Mardi Gras

While Mardi Gras may be celebrated all over the world as a raucous holiday full of satire, mockery, and breaking from tradition, New Orleans is the only place synonymous with the Carnival season the world over. Extravagant balls are hosted by social clubs and organizations who put on the famous parades of New Orleans Mardi Gras. Krewes collect beads, doubloons, stuffed animals, and other “throws” to bestow upon parade-goers as their floats, marching bands, costumed dancers, flambeaux, and their very own royaltystrut down St. Charles Ave.

Mardi Gras might stir up visions of laughter and joy, parades, costumes, beads, and delicious bavarian creme-filled king cakes, but there is a darker side to the festive masquerade. Elaborate masks cover the faces of reality beneath a deep and colorful veil. Delectable indulgences of every kind are realized before they have to be discreetly tucked away during Lent, a time of penance. Deep pagan roots and profound racial ties lie at the heart of this jubilant season, where death and chaos become themes not of Halloween, but of Mardi Gras itself…

New Orleans Mardi Gras History 101

Beginning on Epiphany (aka Three Kings Day or Twelfth Night) and ending on Fat Tuesday (aka Shrove Tuesday or Mardi Gras Day) is the season known as Carnival. Mardi Gras, French for “Fat Tuesday”, is the celebrated method of indulgence and debauchery before the fasting of Lent. A “farewell to the flesh” (no it is a CELEBRATION OF THE FLESH), it’s the only time of year in Louisiana that is acceptable to feast on King Cake, a traditionally circular shaped cinnamon pastry covered in frosting and colored sugar. A time when the colors of purple (for justice), green (for faith), and gold (for power) reign supreme and adorn every decoration on every door and balcony of the French Quarter.

Carnival parades were first held in New Orleans in 1837, even though the festive season was believed to be celebrated as far back as 1699. The first floats appeared twenty years later in 1857 with the Mistick Krewe of Comus, the oldest Mardi Gras Krewe in the city and is still active today.

Flambeaux: In the 18th and 19th centuries, electric lighting was not readily available, so torch-bearers, or “Flambeaux”, marched at the head of the parade to light the way. Slaves and free African-Americans were commonly used in these rolls. The tradition marches on to this day, although people of all races and backgrounds carry the flambeaux torch and provide parade entertainment by spinning and dancing with the flame.

Hail Rex!: First ascending to the Carnival throne in 1872, Rex, hereby named the “King of Carnival” is synonymous with New Orleans Mardi Gras like Harry Connick Jr. is synonymous with modern jazz. The first Rex was the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia, a prominent visitor to New Orleans and the post Civil-War south during the time of reconstruction. The King of Carnival is always a prominent person of New Orleans and given a symbolic key to the city by the New Orleans mayor. “Hail Rex” is sounded with cheer as the acclaimed King of Carnival parades the streets during the spectacle of the Rex parade on Mardi Gras day.

Mardi Gras Indians and Baby Dolls: Mardi Gras Indian tribes of African-American men have a long-standing tradition on the backstreets of New Orleans. They don their beautiful handmade, articularly beaded, colorfully feathered, and immaculate costumes to salute their heritage. The Native Americans took in runaway slaves and freedmen, treating them in as their fellow man, protecting them, and teaching their culture. The Mardi Gras Indian tribes are a way to pay respect to the people who influenced and provided for them.

What is Mardi Gras? The REAL History & Traditions Explained.

What is Mardi Gras? The REAL History & Traditions Explained.

The History of Super Sunday and the Mardi Gras Indians

spacer

African-American prostitutesof infamous Storyville had a nickname their clients called them… “baby dolls.” Dressed as adult-sized baby dolls with satin bloomers and bonnets, the women took to the street parades during Carnival time in the hopes of getting more work. Today, the baby dolls are still parading, only this time for the fun, honor of the past, and pure joy of it!

Masks: Dating as far back as pagan Rome, “masking” was a way to hide your identity and inhibitions. Elaborate and folk-art style masks worn today for New Orleans Mardi Gras are reminiscent of the masks of Carnivale in Venice, Italy.

Revelers who were generally excluded from the festivities in the Crescent City in the era of Jim Crow used the opportunity to conceal themselves and join in on the fun. In New Orleans today, it is actually required by law that float riders in Mardi Gras parades must be masked. Exceptions are made for notable figures, celebrities, and carnival royalty.

Throwing of Beads: Purple, representing justice, green, representing faith, and gold, representing power, are the traditional colors of the Mardi Gras season. The first and most notable daytime parade, Rex, and their crowned King chose the colors and it is still used to this day. The idea behind beads came from these carnival colors; glass beads were made and bestowed upon the person the King of Carnival (Rex) felt best represented their meaning. Glass beads are not exactly meant to be thrown though, so it wasn’t until the invention of the plastic Mardi Gras beads that they were actually tossed from the floats during the parades, the staple tradition of Mardi Gras that we see today.

Pagan Rituals of Lupercalia and Saturnalia

Declared a legal holiday in Louisiana in 1875, Mardi Gras actually dates back thousands of years to pagan spring and fertility celebrations in ancient Rome. When Christianity first arrived in Rome, the traditions of pagan Lupercalia and Saturnalia weren’t eradicated, instead they were carried on and incorporated into their new Christian (ROMAN) religion.

Lupercalia was a three day long fertility festival that took place in February. Cleansing the ancient city of evil spiritsand unleashing health, fertility, and rebirth was the purpose of Lupercalia. The celebration was also known as “dies Februtas”, named after the purification instrument of “februa”, which gave February (Februarius) its name. The Feast of Lupercal is a famous scene in William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.

Saturnalia, an ancient festival honoring the sun God Saturn, was traditionally held in December. Celebrated with a sacrifice, a subsequent feast, gift-giving, and a general carnival-like ambiance, the custom was to elect a “King of the Saturnalia” (sound familiar) and he would reign over the ongoing festivities.

The general cleansing or a “farewell to the flesh” of Lupercalia, the election of a King of Saturnalia, the feasts, merry-making, and festivities of both pagan rituals, I think it’s pretty clear where the roots of our very own Mardi Gras lie.

Courir de Mardi Gras

A medieval French custom turned meridional tradition, Courir de Mardi Gras, or “Mardi Gras run”, takes place in the rustic parts of southern Louisiana at sunrise on Mardi Gras Day. The “run” was a means to collect ingredients to concoct a communal gumbo. Revelers gathered together and paraded to local farms and homes begging for ingredients along the way, ending in a feast only Fat Tuesday could achieve.

During early European begging rituals like that of Halloween, mumming, wassailing, and fête de la quémande (“feast of begging”); begging from house to house, manor to manor, and castle to castle was considered asmissable behavior and socially acceptable. Handmade costumes and masks allowed for concealing identity, parodying authority figures such as clergy and nobility, and role reversals. The upper class ruled the land and the poor were left to beg for food, so groups gathered together and danced and sang in exchange for the generous offerings bestowed upon them.

In Louisiana, these folk traditions were brought by the settlers of Celtic and French Europeinto the Acadia region during the 17th and 18th centuries. Although the culture began to fade in the 1930s and 40s due to WWII, it revived again in the 50s and 60s and is prevalent today with more modern twists. Blindfolds, macabre masks, animal masks, antlers, and other strange paraphernalia are genuine wear for Courir de Mardi Grasand the customs even appeared on television episodes of Treme and True Detective.

Tradition: Dancing, drinking,begging, feasting, whipping, and penitence are all customary Courir de Mardi Gras traditions. In the early morning hours of Fat Tuesday, the riders gather at a central meeting place and Le Capitaine (the leader of the Mardi Gras) and his co-capitaines shout out the rules that must be adhered to by all of the revelers. The Capitaine can be identified by his cape and small flag, riding on horseback. Once the revelers, or “Mardi Gras” as they are called collectively, are organized then the drums and other instruments begin to play and they process to the first location. The Capitaine approaches first, requesting permission to enter the private property while the spirit of gaietytakes over the band of “Mardi Gras.” They attempt to sneak on the property while the Capitaines chase and scold them using their burlap whips. Hijinks, horseplay, and all manner of pranks are played on the farmers while begging for food and ingredients for the gumbo. Chicken, sausage, rice, and vegetables are all prize winning ingredients, but a LIVE chicken bolsters the most excitement and the drunken Mardi Gras run through the mud to catch them.

Mardi Gras Capuchons

Miter hats, mortarboards, capuchons (the wizard/witches cone aka the dunce cap),handmade costumes of old work clothes, patchwork designs, masks made of wire mesh with painted and animal features are all fashionable for Courir even to this day. Revelers now use trucks and trailers as a means to move along their routes in addition to horseback, but the centuries old tradition of Courir de mardi Gras is still very much alive and well in rural Louisiana.

You can see for yourself the folkstyle celebration in the countryside in Basile, Choupic, Church Point, Duralde, Elton, Eunice, Gheens, Mamou, Soileau, South Cameron, and Tee Mamou-lota Louisiana.

spacer

The North Side Skull and Bone Gang

Imagine seeing a group of maskers parading down your street at 5:30am on Mardi Gras morning, dressed as skeletons, the leader wearing an antler helmet, and all while loudly exclaiming “We come to remind you before you die. You better get your life together. Next time you see us, it’s too late to cry!” They knock on your doors and windows, you better run outside so you can see them before they disappear until next year!

The North Side Skull and Bone Gang is a tradition that’s been held for 200 years in the Treme. Rooted in African spirituality,meant to arise family spirits back from the cemetery to parade alongside their ancestors on Mardi Gras Day. You can witness this uniquely New Orleans Mardi Gras tradition by visiting the Backstreet Cultural Museum at 5am on Fat Tuesday morning when they leave on their mission of spreading peace. You might just hear the sound of drums beating and Chief Bruce “Sunpie” Barnes shouting “If you don’t live right, the Bone Man is commin’ for ya!”

The Ghosts of Mardi Gras Past

The famed Arnaud’s Restaurant was opened in 1918 by Count Arnaud Cazenave, his beautiful daughter Germaine was just 16 at the time. Due to her father’s immense wealth and fame, along with her unwavering beauty, Germaine was repeatedly crowned Queen of Mardi Gras, elected more times than any other woman in New Orleans history. On one of her crowned years she had the perfect Mardi Gras gown handmade just for her, so perfect in fact, that she requested a duplicate gown that she could later be buried in. The elaborate horse-drawn carriage Easter parade to St. Louis Cathedral from Arnaud’s was another claim to fame that Germaine started in 1956, inspired by the Easter strollers of New York’s Fifth Ave that were popular at the time.

Adorned in her favorite royal gown, Germaine Cazenave Wells’ spirit is frequently seen moving about the Mardi Gras museum inside of Arnaud’s Restaurant where her memorabilia is lovingly displayed, including her past gowns resting on the shoulders of mannequins with her resemblance. Even without her specter strolling about, it sounds like the visions of the museum itself are enough to startle one at first. Her father’s spirit likes to hang around the bar, perhaps she is there to join him for a drink and celebrate their favorite holiday?

spacer

(Photo: Nance Carter)

The blood drips off the bones onto the children while they sleep… This from the most memorable tour and craziest story heard during my week-long stay in New Orleans. It was told to me and others in our group by Jerry while walking along N. Rampart Street on the way to the cemetery. We were part of the Voodoo Tour run by the New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum on Dumaine Street between Royal and Bourbon. If you want the real deal, go on this tour and not one of the voodoo tours run by tour companies in the city.

New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum

The secret Voodoo mission takes place every year, going back as far as 1819. It begins on the eve of Fat Tuesday, the day before Christian fasting and sacrifice – the next day being Ash Wednesday, the beginning of Lent. Fat Tuesday is traditionally the last day to stuff your face, drink yourself silly, and overindulge in anything you plan to give up for the 40 days of Lent.

As the revelers in the city don colorful and elaborate costumes representing the chosen theme of their parade, the Skull and Bone gangs of the Voodoo tradition wear black sweats on which they have painted white skeleton bones. Instead of elaborately painted and feathered masks, their faces are covered by oversize paper mache skulls. They join together in Congo Square, just north of the touristy French Quarter, and perform a religious rite as dawn approaches. They ask the spirits for strength of purpose to do well what their faith commends them to do.

After the ceremony at Congo Square, the gangs split up throughout the Lower 6th and 7th Wards to seek out the children. Their pots and pans clang in the silent morning as the skeletons make their presence known. They carry calf and pig bones, blood dripping from bits of meat still on the bones. The houses they enter have been chosen by the owners’ beforehand. Parents usher the skull and bone members into the house and toward the children’s rooms. The skeletons chant over the sleeping bodies, while the blood drips off the bones onto the children while they sleep. If the kids don’t wake up, they are tap-tap-tapped awake, and told to be good and act correct, or the skeletons will come to get them before their time. That mission complete, it’s on to the next house.

spacer

Mardi Gras

Just Harmless Fun?

Billed as the “greatest free party on earth,” Mardi Gras is celebrated by millions around the world. But what is the origin of this event—and should it be celebrated?

It’s that time of the year—Mardi Gras! Time for one of the biggest parties on the planet to begin.

A Popular Festival

Mardi Gras (also called “Carnival” in many countries) is a time of unrestrained merrymaking, in which participants passionately indulge every fleshly desire. Celebrated predominantly in Roman Catholic communities in Europe and Latin America, pre-Lenten carnivals are spreading in the U.S. Some of the more famous celebrations occur in New Orleans, Louisiana; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago; Nice, France; and Cologne, Germany.

This festival is so popular that millions celebrate it. For example, three million people flock to New Orleans annually to participate in what is often billed as “the greatest free show on earth.” It adds an estimated $1 billion to the city’s economy, and its population more than doubles during the week leading up to Fat Tuesday.

While this festival is highly popular, is it merely harmless fun?

Even though Carnival is observed around the world, let’s consider more closely how Mardi Gras is celebrated in America.

From Ancient Times

This may come as a surprise, but Mardi Gras long predates Christianity. The earliest record comes from ancient times, when tribes celebrated a fertility festival that welcomed the arrival of spring, a time of renewal of life. The Romans called this pagan festival Lupercalia in honor of “Lupercus,” the Roman god of fertility. Lupercalia was a drunken orgy of merrymaking held each February in Rome, after which participants fasted for 40 days.

Interestingly, similar to modern celebrations, the Romans donned masks, dressed in costumes and indulged all of their fleshly desires as they gave themselves to the gods “Bacchus” (god of wine) and “Venus” (goddess of love). The masks and costumes were used as disguises to allow sexual liberties not normally permitted as individuals engaged in “bacchanal,” the drunken and riotous occasion in honor of Bacchus. (The word “bacchanal” is still associated with Carnival celebrations to this day.)

As pagans converted to Catholicism, they did not want to give up this popular celebration. Church leaders, seeing that it was impossible to divorce the new converts from their pagan customs, decided to “Christianize” this festival. Thus, Carnival was created as a time of merrymaking immediately preceding their pagan 40-day fast, which the church renamed “Lent.” During Carnival, participants indulged in madness and all aspects of pleasure allowable, including gluttony, drunkenness and fornication.

The festival then spread to Europe, where it was celebrated in England, Spain, Germany, France and other countries. During the Middle Ages, a festival similar to the present-day Mardi Gras was given by monarchs and lords prior to Lent. To conscript new knights into service, the nobles would hold feasts in their honor, and they would ride through the countryside rewarding peasants with cakes (thought by some to be the origin of the “King Cake,” to be explained later), coins (probably the origin of present day Mardi gifts of “doubloons”) and other trinkets.

In Germany, there is a Carnival similar to Mardi Gras known as “Fasching,” held during the same period. To a lesser extent, this festivity is also celebrated in Spain and France.

In France, the festival was called Mardi Gras, meaning “Fat Tuesday.” This name comes from the ancient pagan practice of killing and eating a fattened calf on the last day of Carnival; it dates from the pre-Christian era when the Druids sacrificed offerings to pagan gods, seeking more fertile women and livestock. This day was also known as “Shrove Tuesday” (from the old English word “shrive,” which means to confess all sins) and “Pancake Tuesday.” The custom of making pancakes came from the need to use up all the fat, eggs and dairy products before the fasting period of Lent began.

spacer

|

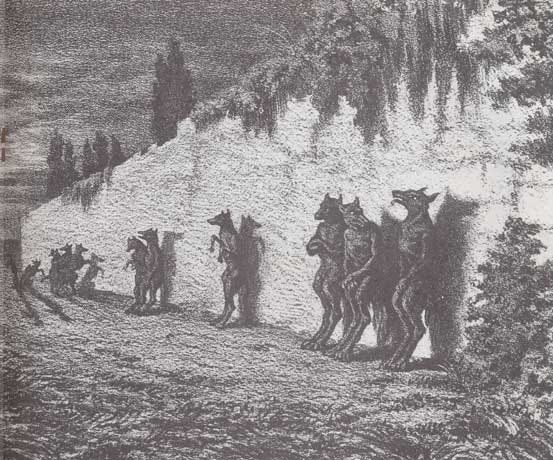

Lycanthropy, (from Greek lykos, “wolf ”; anthropos, “man”), mental disorder in which the patient believes that he is a wolf or some other nonhuman animal. Undoubtedly stimulated by the once widespread superstition that lycanthropy is a supernatural condition in which men actually assume the physical form of werewolves or other animals, the delusion has been most likely to occur among people who believe in reincarnation and the transmigration of souls.

MOST pagan religions believe in reincarnation and tranmigration of souls. That is why lycanthropy is returning right along with PAGANISM.

Usually, a person is deemed to take the form of the most dangerous beast of prey of the region: the wolf or bear in Europe and northern Asia, the hyena or leopard in Africa, and the tiger in India, China, Japan, and elsewhere in Asia; but other animals are mentioned too. Both the superstition and the psychiatric disorder are linked with belief in animal guardian spirits, vampires, totemism, witches, and werewolves. The folklore, fairy tales, and legends of many nations and peoples show evidence of lycanthropic belief.

spacer

The True Werewolf History of Valentine’s Day

By

Romulus and Remus created quite a bit of chaos by their birth. Even more so because these twins were the children of demi-gods. Their dad was Mars, the god of war and their mom a forest diety named Rhea Silva.

As a result, these powerful babies Romulus and Remus scared the emperor. He ordered them abandoned in the woods and left to die in the middle of winter. He also locked their mom Rhea Silva in a convent.

But the emperor didn’t know that Rhea Silva, whose name means “forest spirit” could still communicate with the animals in the forest. She made a deal with a powerful she-wolf named Lupa that if Lupa would adopt her sons and give them milk to save their lives, that she would share them with Lupa on every full moon.

Lupa agreed to the deal and found Romulus and Remus deep in the woods, roughly on this day in February. She fed them her own milk and this caused the physiological changes that would save their lives and turn them into werewolves on the full moon. So that when they became adults, on every full moon the twins would turn into werewolves and always return to her in the forest.

spacer

Pan’s connection to Lupercalia and wolves

Saturday, February 6, 2010

There are many stories surrounding the festival of Lupercalia and its origins. As you may know, Lupercalia has to do with wolves. Wolves and the god of shepherds, sheep, and goats? Sounds like an oxymoron, but yes, there is a connection between Pan, Lupercalia, and wolves.

While Lupercalia is primarily a Roman festival, it has its origins in Ancient Greece. Originally male adolescents in Arkadia would reenact the feast of Lycaon and the gods every year. At the original feast, Lycaon prepared a feast for the Olympian gods that included some human flesh, perhaps from one of Lycaon’s male relatives. This so enraged Zeus, that he struck Lycaon’s house with a thunderbolt.

While Lupercalia is primarily a Roman festival, it has its origins in Ancient Greece. Originally male adolescents in Arkadia would reenact the feast of Lycaon and the gods every year. At the original feast, Lycaon prepared a feast for the Olympian gods that included some human flesh, perhaps from one of Lycaon’s male relatives. This so enraged Zeus, that he struck Lycaon’s house with a thunderbolt.

At the Arkadian reenactment, the teenagers would gather on a mountaintop and partake of a meal of animal entrails. However, amongst the animal guts was hidden one piece of human intestine. If a participant ate this juicy morsel, he would turn into a wolf and was only able to become human again if he refrained from eating human meat for nine years. Another way that the boys could achieve this lupine transformation was to swim across a special mountain pool. Once again, after nine years, they could regain their human form.

How does this relate to Pan? Arkadia is one of Pan’s original domains, so therefore he was naturally involved. In fact, he was sometimes referred to as Lykaian Pan (Wolf Pan) because it was believed that he held the secret to becoming a werewolf and controlling them. This belief traveled to Rome via Hermes’ son, Euandros, who exported the cult of Pan Lykaios and the festival of Lykaia (remember where the boys would eat humans) to Italy. This festival later became the festival of Lupercalia.

How does this relate to Pan? Arkadia is one of Pan’s original domains, so therefore he was naturally involved. In fact, he was sometimes referred to as Lykaian Pan (Wolf Pan) because it was believed that he held the secret to becoming a werewolf and controlling them. This belief traveled to Rome via Hermes’ son, Euandros, who exported the cult of Pan Lykaios and the festival of Lykaia (remember where the boys would eat humans) to Italy. This festival later became the festival of Lupercalia.

Once the wolf festival was transported to Rome and became Lupercalia, many different stories and deities became associated with the celebration. However, Pan still kept his hooves’ involved in the festivities. To honor Pan, two goats and a dog were annually sacrificed. The dog was sacrificed because they were sacred for their ability to protect flocks and because Pan raised hounds. Skin from the sacrificed goats was used for the flails that the  Lupercalia runners would whip the female spectators with. It was believed that through this aggressive behavior Pan would bless the ladies with fertility.

Lupercalia runners would whip the female spectators with. It was believed that through this aggressive behavior Pan would bless the ladies with fertility.

Besides being linked to wolves through Lupercalia and the Lykaia celebration, Pan is also linked to wolves through other myths. One myth is a version of the Echo story. Upon her refusal of Pan’s love and affection, Pan turned a group of shepherds into wolves and had them chase Echo and tear her to pieces. In other myths Pan turns shepherds that disturb him during his noon nap into wolves and have them devour their flocks. Occasionally, the sheep and goats would be turned into wolves to attack a shepherd who had displeased Pan.

Pan is not just the god of flocks and shepherds. As master of Arkadia, he has the power to change humans and animals into wolves and other creatures, but that’s another story.

Supernatural Legend of New Orleans: The Rougarou

What Is The Rougarou?

Standing at a terrifying ten feet tall, the dark-haired, long-fanged beast with bright-red eyes regularly kills livestock, pets, wildlife and even people. Some say they only arrive during the full moon, like a werewolf, while others have claimed that the horrifying creature roams the land year-round. The terrifying creature has superhuman strength and speed. However, they aren’t unstoppable. A rougarou’s only weakness is fire, which can destroy them, as well as decapitation.

Many stories of the rougarou detail its presence in the bayou or its rein of terror throughout small towns. However, some people used the stories to cause fear. Long ago, it was a famous tale that the rougarou would feast upon young Catholics if they didn’t practice Lent. Also, elders used to use this story to make their grandkids behave. They did this by telling them the rougarou would eat them if they didn’t behave.

Stories of the Rougarou

Individuals become rougarou’s through contact, much like the stories of the werewolf. The infection’s transferred through bites or making direct eye contact with their blood-red eyes. However, anyone who survives an encounter with a loup-garou is said to be able to beat the curse by remaining silent about it for a hundred and one days, and then they’re released from the affliction. A witch can cast a spell upon someone to turn them as well. Some people in historical legends do this voluntarily, to gain the immense power that comes with the curse.

Much like the notorious Bigfoot, vampire, and ghost, the rougarou is a mystery many people are still working to discover. The evil entity stalks the lands in search of helpless prey and has for centuries throughout Louisiana. While nothing can be entirely confirmed about the rougarou, one thing is sure: if the rougarou does exist, it’s incredibly elusive and dangerous. Perhaps stories of this supernatural and fabled canine can convince you to come to New Orleans, Louisiana!

spacer

Imagine that you are a fisherman, out in the bayous in the marshland south of New Orleans. Today has been a long, arduous day, and you find that you’ve lost track of time. In fact, the sun has set completely. You wouldn’t be able to see at all, if not for the full moon overhead. But even so, as the temperature cools, fog seeps over the still bayou around you. Sure, it’s dark, but there’s just enough light for you to see where you’re going, which is all you really need. You begin to head home, spearing the murky water with your paddle. Suddenly, you hear a bone-chilling howl that rattles through the mossy cypress trees, compelling you to stop for a minute. It’s strange — the howl sounds like no dog or coyote you’ve ever heard. There are no wolves in the swamp, either. Could it be a feral child, set loose into the wilderness? No, you know better. You remember the countless stories that your mother and grandmother once told you to keep you from going out at night. It’s got to be the Rougarou, the infamous werewolf of the bayou.

The creature is described as half-man, half-dog. It stands upright on two legs, and is covered in hair. It has the face of a canine with many sharp, frightening teeth. Its fingernails are grisly claws. The Rougarou roams the bayou in search for misbehaving children to frighten.

Driving down nearly any scenic highway or quaint backroad in Louisiana will lead you through a beautiful and somewhat mythical landscape. In the daytime, you are met with lush greenery and nearly endless waterways, freckled with boats, fishermen, and potentially haunted buildings. In the nighttime, you see a landscape lit up only by the occasional light seeping through a window and the gleaming red eyes of the alligators, which lurk beneath the water’s surface. An orchestra of various birds, frogs, and insects are always singing. Countless spiders hang their elaborate tapestries between oak trees that have been there longer than any man has. It is no wonder that monsters like Rougarou are so pervasive in this region’s folklore. But what is the Rougarou, and where does a myth like this come from?

The creature originates from a similar beast, Loup-Garou, which appears in Medieval French folklore. This 16th century monster was used consistently as a scapegoat. It was easier to blame disappeared village children, stolen property, or mysterious happenings on the Loup-Garou than going through with complicated criminal investigations. If a person was demonstrating strange behavior, villagers might condemn them as Loup-Garou. The suspected Loup-Garou would then be put on trial, where the court would usually produce a guilty verdict. Over time, the Loup-Garou became a tool used by both the Catholic church to make sure that its followers obeyed the rules of Lent. If one refused to observe Lent for seven consecutive years, legend says that he would be transformed into a Loup-Garou.

This legend followed French settlers to the Acadia region, located in present-day Eastern Canada. Among these settlers is where Cajun culture was born. After the French and Indian War, British officers deported the Acadians to various American colonies. These Acadians were eventually invited by the Spanish to settle in what is now Louisiana. Loup-Garou became Rougarou in Cajun French, and the monster continued to thrive down in the swamps of Louisiana. Cajun culture is still vibrant and instrumental to the history of this state.

Today, the Rougarou is a celebrated piece of folklore. In fact, it even has its own festival. On the last weekend of October down in Houma, Rougarou Fest rages through the city’s streets. The festival involves food, live music, a parade, and lots of activities for children. Best of all, this spooky fanfare can be observed for free. Here, Louisianians and visitors alike can pay homage to the monstrous werewolf and continue to spread the centuries-old oral tradition. Beat that, Bigfoot.

spacer

‘Twilight’ doesn’t do justice to this beast’s badass backstory.

New Visions

Oct 14, 2016 · 5 min read

European concepts of the werewolf emerged from the warrior class of Germanic tribes, who revered the wolf as a potent symbol of hunter and fighter. Boys coming of age would symbolically become wolves through ritual.The French word for werewolf, loup garou, originally comes from the Norman Frankish tribal word werwolf, or “wolf man,” which filtered through Low Latin as gerulphus, which the French misheard as garez-vous, or “beware.” So loup garou can be translated both as “wolf to beware of” or the rather redundant “wolf-man-wolf.”

The concept really caught on in France. One of the first mentions of a werewolf in print was Marie de France’s poem “Bisclavret,” circa 1200. A Brittany baron, Bisclavret disappears for three days of every week. Eventually, he tells his wife he is transforming into a wolf, hiding his clothes so he can change back to human form. Horrified, the baroness has her husband’s clothes stolen, trapping him in wolf form, and she remarries. Her treachery is eventually uncovered, and Bisclavret regains human form — after tearing his ex-wife’s nose off.

With the rise of Christianity in the Middle Ages, Germanic pagan beliefs were suppressed and wolf-men became associated with the devil. Europe’s first witch trials were held in 1428 in Valais, a French-speaking area that’s now Switzerland. Alleged witches were accused of raiding cattle in werewolf form. Trials like these spread across Europe, peaking in the 1600s and dying out in the 1700s.

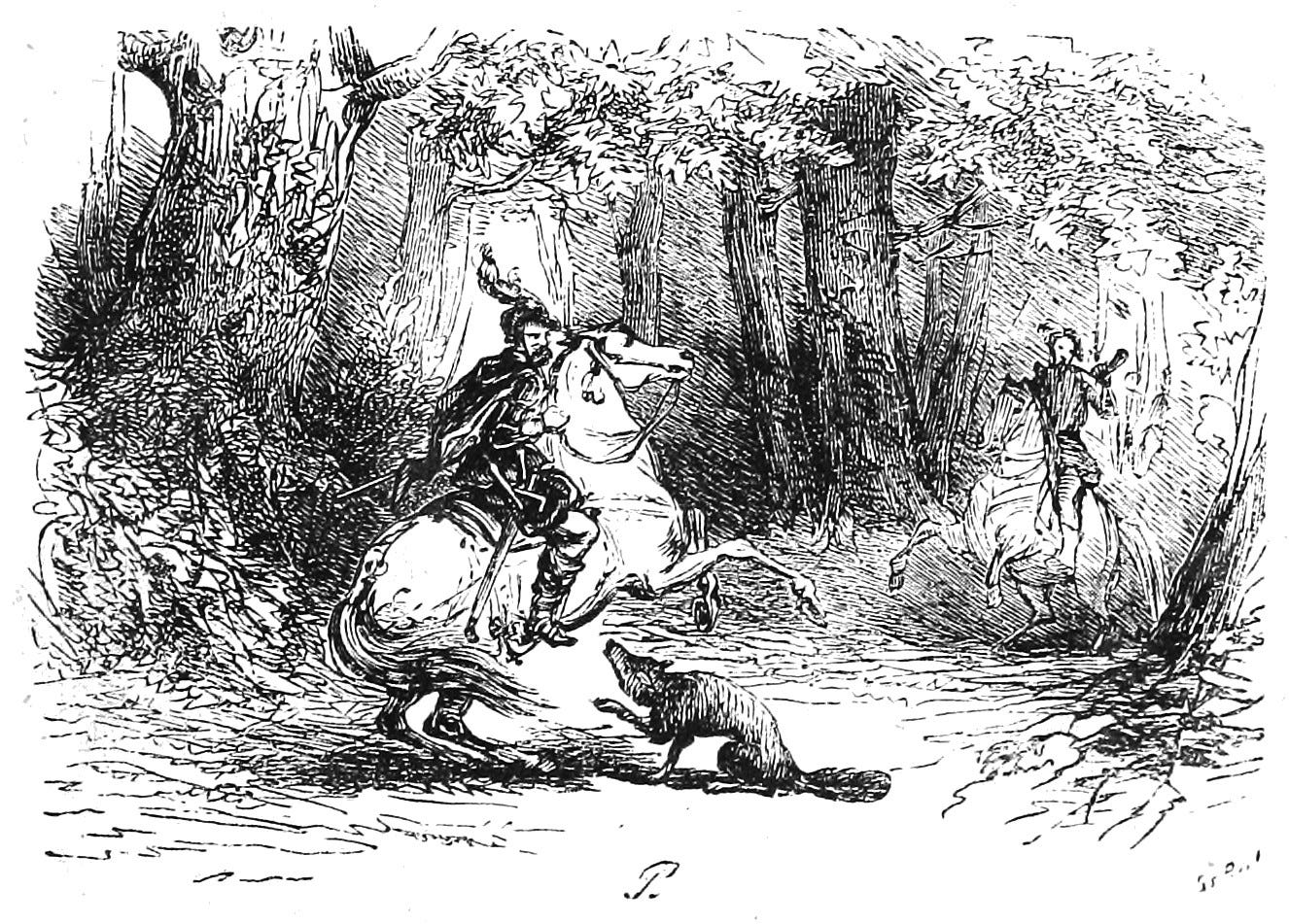

Just as the trials were dying out, people began dying in the rural Gévaudan region of southern France in 1764. Corpses were found horribly mutilated, their throats torn out. Survivors of attacks gave numerous, well-documented accounts of a ravenous wolf the size of a horse, with a terrible roar.

“All who have written to me regarding the size of this animal agree that it is larger than a wolf…some say it is a hyena, others a panther, still others a loup-cervier; this is all I know for certain about this terrible animal.”

—Local official M. de Lachadenède, Oct. 1764

Among panicked peasants, there was speculation the attacks were the work of a loup garou. Famed wolf hunters (yes, they had those) were called in, and thousands of people scoured the woods and valleys hunting for the “Beast of Gévaudan.” They killed more than 100 wolves, and thought they’d killed the beast on numerous occasions, but the attacks continued, claiming up to 113 lives over three years. French tradition credits local hunter Jean Chastel with killing the beast — writers spiced up the tale by saying he’d used a silver bullet.

Biologist Karl-Hans Taake, however, says the beast was probably killed by poison bait, which had been laid across much of the area. After a close review of the considerable historical record, Taake is also certain that the beast was no wolf, and certainly not a loup garou. In National Geographic, he writes that “There can be no reasonable doubt that the Beast was a lion, namely a subadult male.” Taake postulated it had escaped from a private menagerie.

When French settlers journeyed to the New World, they brought the loup garou with them.

“In French Canada, a man (always a man) becomes a loup-garou because of some punishment from heaven. One man, for instance, found that he was a loup-garou because he had not been to Mass (or confession) for ten years. Deliverance from the state of loup-garou comes by religious exorcism, by a blow to the head, or by the shedding of his blood while in the metamorphosed state.” — Maria Leach, Standard Dictionary of Folklore

To this day, French Canadians go on annual loup garou hunts. In Louisiana, Cajun parents warn their children that the loup garou, or hougarou, will eat them if they misbehave.

“In one way or another, everybody believes in it,” Barry J. Ancelet, professor of French at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette told the student newspaper of Nicholls State University. “Whether they believe seriously that there is a character who roams the night or not is unimportant. They believe in the stories…It becomes a way of connecting one generation to the next.”

In Canada, Haiti and Louisiana, a loup-garou doesn’t even have to be a wolf-man, but can transform into a horse, a pig or even a tree.

In Haiti, some versions of loup garou aren’t shapeshifters at all, but “once-human beasts whose souls have been devoured.” Anyone you know could be a loup garou, and the accusation was quickly levied against cheaters and deceivers, or just anyone who had had an unexpected stroke of good — or bad — fortune.

Still, at Halloween time, the image that persists in most of our minds is a towering wolf-man with huge claws and slavering jaws. And for that, like beef bourguignon and coq au vin, we largely have the French to thank.spac

spacer

The werewolf is a staple of supernatural fiction, whether it be film, television, or literature. You might think this snarling creature is a creation of the Medieval and Early Modern periods, a result of the superstitions surrounding magic and witchcraft.

In reality, the werewolf is far older than that. The earliest surviving example of man-to-wolf transformation is found in The Epic of Gilgamesh from around 2,100 BC. However, the werewolf as we now know it first appeared in ancient Greece and Rome, in ethnographic, poetic and philosophical texts.

These stories of the transformed beast are usually mythological, although some have a basis in local histories, religions and cults. In 425 BC, Greek historian Herodotus described the Neuri, a nomadic tribe of magical men who changed into wolf shapes for several days of the year. The Neuri were from Scythia, land that is now part of Russia. Using wolf skins for warmth is not outside the realm of possibility for inhabitants of such a harsh climate: this is likely the reason Herodotus described their practice as “transformation”.

A werewolf in a German woodcut, circa 1512. WikimediaThe werewolf myth became integrated with the local history of Arcadia, a region of Greece. Here, Zeus was worshipped as Lycaean Zeus (“Wolf Zeus”). In 380 BC, Greek philosopher Plato told a story in the Republic about the “protector-turned-tyrant” of the shrine of Lycaean Zeus. In this short passage, the character Socrates remarks: “The story goes that he who tastes of the one bit of human entrails minced up with those of other victims is inevitably transformed into a wolf.”

Literary evidence suggests cult members mixed human flesh into their ritual sacrifice to Zeus. Both Pliny the Elder and Pausanias discuss the participation of a young athlete, Damarchus, in the Arcadian sacrifice of an adolescent boy: when Damarchus was compelled to taste the entrails of the young boy, he was transformed into a wolf for nine years. Recent archaeological evidence suggests that human sacrifice may have been practised at this site.

Monsters and men

The most interesting aspect of Plato’s passage concerns the “protector-turned-tyrant”, also known as the mythical king, Lycaon. Expanded further in Latin texts, most notably Hyginus’s Fabulae and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Lycaon’s story contains all the elements of a modern werewolf tale: immoral behaviour, murder and cannibalism.

An Athenian vase depicting a man in a wolf skin, circa 460 BC. WikimediaIn Fabulae, the sons of Lycaon sacrificed their youngest brother to prove Zeus’s weakness. They served the corpse as a pseudo-feast and attempting to trick the god into eating it. A furious Zeus slayed the sons with a lightning bolt and transformed their father into a wolf. In Ovid’s version, Lycaon murdered and mutilated a protected hostage of Zeus, but suffered the same consequences.

Ovid’s passage is one of the only ancient sources that goes into detail on the act of transformation. His description of the metamorphosis uses haunting language that creates a correlation between Lycaon’s behaviour and the physical manipulation of his body:

…He tried to speak, but his voice broke into

an echoing howl. His ravening soul infected his jaws; his murderous longings were turned on the cattle; he still was possessed by bloodlust, His garments were changed to a shaggy coat and his armsinto legs. He was now transformed into a wolf.

Ovid’s Lycaon is the origin of the modern werewolf, as the physical manipulation of his body hinges on his prior immoral behaviour. It is this that has contributed to the establishment of the “monstrous werewolf” trope of modern fiction.

Lycaon’s character defects are physically grafted onto his body, manipulating his human form until he becomes that which his behaviour suggests. And, perhaps most importantly, Lycaon begins the idea that to transform into a werewolf you must first be a monster.space

spacer

Spring was thought to begin on February 5, which was the time for the seed to be sown. It was a time, too, for purification and the expiation of any unintentional offense that might have been given to the gods. The month of February takes its name, in fact, from the instruments of purification (februa) used in such rites, the best known of which is the Lupercalia. source

Lupercalia

Article by Leonhard Schmitz, Ph.D., F.R.S.E., Rector of the High School of Edinburgh

on p718 of

William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D.:

A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, 1875.

LUPERCA′LIA, one of the most ancient Roman festivals, which was celebrated every year in honour of Lupercus, the god of fertility.b All the ceremonies with which it was held, and all we know of its history, shows that it was originally a shepherd-festival (Plut. Caes. 61). Hence its introduction at Rome was connected with the names of Romulus and Remus, the kings of shepherds. Greek writers and their followers among the Romans represent it as a festival of Pan, and ascribe its introduction to the Arcadian Evander. This misrepresentation arose partly from the desire of these writers to identify the Roman divinities with those of Greece, and partly from its rude and almost savage ceremonies, which certainly are a proof that the festival must have originated in the remotest antiquity. The festival was held every year, on the 15th of February,c in the Lupercal, where Romulus and Remus were said to have been nurtured by the she-wolf; the place contained an altar and a grove sacred to the god Lupercus (Aurel. Vict. de Orig. Gent. Rom. 22; Ovid. Fast. II.267). Here the Luperci assembled on the day of the Lupercalia, and sacrificed to the god goats and young dogs, which animals are remarkable for their strong sexual instinct, and thus were appropriate sacrifices to the god of fertility (Plut. Rom. 21; Servius ad Aen. VIII.343).d Two youths of noble birth were then led to the Luperci, and one of the latter touched their foreheads with a sword dipped in the blood of the victims; other Luperci immediately after wiped off the bloody spots with wool dipped in milk. Hereupon the two youths were obliged to break out into a shout of laughter. This ceremony was probably a symbolical purification of the shepherds. After the sacrifice was over, the Luperci partook of a meal, at which they were plentifully supplied with wine (Val. Max. II.2.9). They then cut the skins of the goats which they had sacrificed, into pieces; with some of which they covered parts of their body in imitation of the god Lupercus, who was represented half naked and half covered with goat-skin. The other pieces of the skins they cut into thongs, and holding them in their hands they ran through the streets of the city, touching or striking with them all persons whom they met in their way, and especially women, who even used to come forward voluntarily for the purpose, since they believed that this ceremony rendered them fruitful, and procured them an easy delivery in childbearing.

…striking the women they met with strips of goat skin, to promote fertility. “Neither potent herbs, nor prayers, nor magic spells shall make of thee a mother,” writes Ovid, “submit with patience to the blows dealt by a fruitful hand.” Source

This act of running about with thongs of goat-skin was a symbolic purification of the land, and that of touching persons a purification of men, for the words by which this act is designated are februare and lustrare (Ovid. Fast. II.31; Fest. s.v. Februarius). The goat-skin itself was called februum, the festive day dies februata, the month in which it occurred Februarius, and the god himself Februus.

The act of purifying and fertilizing, which, as we have seen, was applied to women, was without doubt originally applied to the flocks, and to the people of the city on the Palatine (Varro, de Ling. Lat. V. p60, Bip.). Festus (s.v. Crepos) says that the Luperci were also called crepi or creppi, from their striking with goatskins (a crepitu pellicularum), but it is more probable that the name crepi was derived from crepa, which was the ancient name for goat (Fest. s.v. Caprae).

The festival of the Lupercalia, though it necessarily lost its original import at the time when the Romans were no longer a nation of shepherds, was yet always observed in commemoration of the founders of the city. Antonius, in his consulship, was one of the Luperci, and not only ran with them half-naked and covered with pieces of goat-skin through the city, but even addressed the people in the forum in this rude attire (Plut. Caes. 61). After the time of Caesar, however, the Lupercalia seem to have been neglected, for Augustus is said to have restored it (Suet. Aug. 31), but he forbade youths (imberbes) to take part in the running. The festival was henceforth celebrated regularly down to the time of the emperor Anastasius. Lupercalia were also celebrated in other towns of Italy and Gaul, for Luperci are mentioned in inscriptions of Velitrae, Praeneste, Nemausus, and other places (Orelli, Inscr. n2251, &c.). (Cf. Luperci; and Hartung, Die Relig. der Römer, vol. II p176, &c.).

spacer

spacer

SUNDAY, MARCH 28, 2010

spacer

spacerspacer

Today the Ursuline Convent stores the Catholic Archives records dating back to 1718. In the 1700’s, the Catholic Diocese sent young girls from the French convents to New Orleans to spread Christian values and find respectable men to marry. They each carried a coffin shaped chest packed with their belongings. The chest was called a “casket” and the young women were mockingly called the Casket Girls. However, the plan backfired. A good number of the girls were raped and forced into prostitution. Ships sailed back to New Orleans to rescue the fair maidens and returned them to France. Some of the girls still carried the small caskets with them and the contents were never revealed. Legend says with the contents still unknown, the Sisters of the Ursuline placed them on the third floor of the convent. The doors and windows were sealed shut for all eternity. When the chests were finally opened many years later, they were found empty. Superstitious citizens claimed the girls had smuggled vampires into New Orleans in the chests instead of clothing and such. The sealed attic of the convent has shuttered windows. The heavy shutters are of an unique style not seen anywhere else within the French Quarter. The shutters are always closed, but they say late at night the shutters open and the vampires come out into New Orleans seeking their prey. The Ursuline Convent claims there is nothing stored in the third floor attic, but then these mysterious questions arise.

spacer

spacer

spacer

While on the tour our guide (haunted New Orleans Tours) told us that about 2 weeks before Katrina hit he was out there doing his tour, as he tuned towards the convent he noticed that on the window all the way to the left the shutter wasn’t just open it was completely gone. This freaked him out so he quickly moved his tour along and the next night he saw that the window was bricked up from the inside. He counted the days, it took them 9 days to fix the shutter because they actually had to wait for a priest to fly in from Rome to bless the nails. So if there is nothing hidden in the attic why the over kill to make sure no one sees what’s actually in it, Also as they tell you on the tour in the 17 & 1800’s you didn’t put shutter on your attic windows because you could actually DIE from the heat because there was no electricity .

Religious rites in many traditional cultures, including on the Hawaiian Islands, incorporated costly offerings—like human sacrifice. JACQUES ARAGO

Human sacrifice may have helped societies become more complex

Religion is often touted as a force for moral good in the world—but it has a sinister side, too, embodied by gruesome rituals like human sacrifice. Now, new research suggests that even this dark side may have served an important function. Scientists have found that these ceremonial killings—intended to appease gods—may have encouraged the development of complex civilizations in maritime Southeast Asia and the South Pacific, though some experts remain unconvinced.

Human sacrifice was part of many traditional cultures across the globe, marking important events like the death of a leader or the construction of a house or boat. In the islands of the Indian and Pacific oceans, powerful chiefs or priests usually carried out the grim rites. They dispatched powerless individuals—often slaves—by cutting off their heads, beating them to death, or crushing them with canoes until they died.

These horrific deeds may have had some unexpected benefits, at least for some members of society. According to a religious evolutionary theory called the “social control hypothesis,” social elites may have used human sacrifice to preserve their power, cementing their status by claiming supernatural approval for their acts. “There is anecdotal evidence from other areas of the world that human sacrifice was used to maintain and control populations,” says psychologist Joseph Watts, a doctoral student who studies cultural evolution at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. But until now, he says, it hadn’t been systematically tested.

Based on linguistic clues, the scientists built family trees showing how the Austronesian cultures likely evolved and how they are related. It’s a technique the group has used in the past to suggest that belief in supernatural punishment promotes political complexity. The family trees allowed them to estimate whether human sacrifice and social stratification arose in the same places, and whether ritualized killings drove changes in class divisions.

Some cultures at each level of social stratification engaged in human sacrifice, but it was more common in those that were harshly divided: Two-thirds of the highly stratified societies practiced the macabre ritual, compared with just one-quarter of the egalitarian societies, the researchers report online today in Nature. The family trees show that human sacrifice and social stratification evolved together. The timing of the traits’ evolution—human sacrifice came first—suggests that cultures were more likely to become strictly divided along class lines if their religious traditions included the grisly rite.

“People often claim that religion underpins morality,” Watts says. This study, however, highlights another aspect of belief in the divine. “It shows how religion can be exploited by social elites to their own benefit.”