There is a very important meeting coming up in November; COP28. Hang on to your hats because they are about to cut loose with all kinds of changes, demands, upheavals. The World will be quite different in just a matter of months.

In this post you will see how we all became slaves to the ruling elite. You will also see that it is a Fraud and has no legal authority. You will see that CHARLES is repeating the works of King Charles I, and why he is the new GLOBAL Climate Change KING.

You will see that “Smart Cities” are not a new idea. They have been in the works, tested and developed since at least the early 2000s. They are ready to implement this technology globally. You will see what cities are already considered “smart cities” and you may very well be surprised.

In this post you will examine the origin and development of the UN program for CARBON ZERO and the Conference of the Parties (COP). It is time that people woke up and realized that these folks have usurped our rights and are implementing obesely ridiculous demands on our time, our money and our environment. Especially in the light of the TRUTH that CO2 is vital to all life on earth and not the reason for the changes we are witnessing in our weather/climate. This agenda needs to be stopped!

spacer

COP28 UAE

spacer

Always the same game…they just swap culprits.

spacer

UN Climate Change Conference – United Arab Emirates …

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

2023 UN Climate Change Conference (UNFCCC COP 28 ...

International Institute for Sustainable Development

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) established an international environmental treaty to combat “dangerous human interference with the climate system“, in part by stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere.[1] It was signed by 154 states at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), informally known as the Earth Summit, held in Rio de Janeiro from 3 to 14 June 1992. Its original secretariat was in Geneva but relocated to Bonn in 1996.[2] It entered into force on 21 March 1994.[3]

The treaty called for ongoing scientific research and regular meetings, negotiations, and future policy agreements designed to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.[3][4]

They seem to have dumped or forgotten about allowing ecosystems to adapt naturally and the protection of food production. All they care about is economic development and their definition of sustainability.

The Kyoto Protocol, which was signed in 1997 and ran from 2005 to 2020, was the first implementation of measures under the UNFCCC. The Kyoto Protocol was superseded by the Paris Agreement, which entered into force in 2016.[5][6] By 2022, the UNFCCC had 198 parties. Its supreme decision-making body, the Conference of the Parties (COP), meets annually to assess progress in dealing with climate change.[7][8] Because key signatory states are not adhering to their individual commitments, the UNFCCC has been criticized as being unsuccessful in reducing the emission of carbon dioxide since its adoption.[9]

|

What’s in a name? When it comes to Tokyo, the capital of Japan, everything. Kyoto and Tokyo may be two different parts of the country, but do they share a history in terms of their name? Tokyo and Kyoto have similar names because Kyoto was once the country’s capital, which Tokyo later became. When writing the two cities’ respective names in Japanese, you’d write Kyoto as 京都 and Tokyo as 東京都. The only difference is the 東, which stands for “east.” The name for Kyoto translates to “imperial capital” and Tokyo “east imperial capital.” |

The treaty established different responsibilities for three categories of signatory states. These categories are developed countries, developed countries with special financial responsibilities, and developing countries.[4] The developed countries, also called Annex 1 countries, originally consisted of 38 states, 13 of which were Eastern European states in transition to democracy and market economies, and the European Union. All belong to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Annex I countries are called upon to adopt national policies and take corresponding measures on the mitigation of climate change by limiting their anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases as well as to report on steps adopted with the aim of returning individually or jointly to their 1990 emission levels.[4] Developed countries with special financial responsibilities are called Annex II countries. They include all Annex I countries with the exception of those in transition to democracy and market economies. Annex II countries are called upon to provide new and additional financial resources to meet the costs incurred by developing countries in complying with their obligation to produce national inventories of their emissions by sources and their removals by sinks for all greenhouse gases not controlled by the Montreal Protocol.[4] Developing countries are then required to submit their inventories to the UNFCCC secretariat.[4]

Treaties

Convention Agreement in 1992

The text of the Convention was produced during the meeting of an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee in New York from 30 April to 9 May 1992. The Convention was adopted on 9 May 1992 and opened for signature on 4 June 1992 at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro (known by its popular title, the Earth Summit).[10] On 12 June 1992, 154 nations signed the UNFCCC, which upon ratification committed signatories’ governments to reduce atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases with the goal of “preventing dangerous anthropogenic interference with Earth’s climate system”. This commitment would require substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions (see the later section, “Stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations”).[1][7] Parties to the Convention have met annually from 1995 in Conferences of the Parties (COPs) to assess progress in dealing with climate change.[8]

Article 3(1) of the Convention[11] states that Parties should act to protect the climate system on the basis of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities”, and that developed country Parties should “take the lead” in addressing climate change. Under Article 4, all Parties make general commitments to address climate change through, for example, climate change mitigation and adapting to the eventual impacts of climate change.[12] Article 4(7) states:[13]

The extent to which developing country Parties will effectively implement their commitments under the Convention will depend on the effective implementation by developed country Parties of their commitments under the Convention related to financial resources and transfer of technology and will take fully into account that economic and social development and poverty eradication are the first and overriding priorities of the developing country Parties.

The Convention specifies the aim of Annex I Parties was stabilizing their greenhouse gas emissions (carbon dioxide and other anthropogenic greenhouse gases not regulated under the Montreal Protocol) at 1990 levels, by 2000.[14]

“UNFCCC” is also the name of the United Nations Secretariat charged with supporting the operation of the convention, with offices on the UN Campus in Bonn, Germany. Offices were formerly located in Haus Carstanjen and in a building on the UN Campus known as Langer Eugen. From 2010 to 2016 the head of the secretariat was Christiana Figueres. In July 2016, Patricia Espinosa succeeded Figueres, and Espinosa was replaced by Simon Stiell in 2022. The secretariat, augmented through the parallel efforts of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), aims to gain consensus through meetings and the discussion of various strategies. Since the signing of the UNFCCC treaty, Conferences of the Parties (COPs) have discussed how to achieve the treaty’s aims.

Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE)

Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE) is a term adopted by the UNFCCC in 2015 to have a better name for this topic than “Article 6”. It refers to Article 6 of the convention’s original text (1992), focusing on six priority areas: education, training, public awareness, public participation, public access to information, and international cooperation on these issues. The implementation of all six areas has been identified as the pivotal factor for everyone to understand and participate in solving the challenges presented by climate change. ACE calls on governments to develop and implement educational and public awareness programmes, train scientific, technical and managerial personnel, foster access to information, and promote public participation in addressing climate change and its effects. It also urges countries to cooperate in this process, by exchanging good practices and lessons learned, and strengthening national institutions. This wide scope of activities is guided by specific objectives that, together, are seen as crucial for effectively implementing climate adaptation and mitigation actions, and for achieving the ultimate objective of the UNFCCC.[15]

Kyoto Protocol

The 1st Conference of the Parties (COP1) decided that the aim of Annex I Parties stabilizing their emissions at 1990 levels by 2000 was “not adequate”,[16] and further discussions at later conferences led to the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. The Kyoto Protocol was concluded and established legally binding obligations under international law, for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in the period 2008–2012.[8] The 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference produced an agreement stating that future global warming should be limited to below 2 °C (3.6 °F) relative to the pre-industrial level.[17] The Kyoto Protocol had two commitment periods, the first of which lasted from 2008 to 2012. The Protocol was amended in 2012 to encompass the second one for the period 2013–2020 in the Doha Amendment.[18]

One of the first tasks set by the UNFCCC was for signatory nations to establish national greenhouse gas inventories of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and removals, which were used to create the 1990 benchmark levels for accession of Annex I countries to the Kyoto Protocol and for the commitment of those countries to GHG reductions. Updated inventories must be submitted annually by Annex I countries.

The US did not ratify the Kyoto Protocol, while Canada denounced it in 2012. The Kyoto Protocol was ratified by all the other Annex I Parties.

All Annex I Parties, excluding the US, participated in the 1st Kyoto commitment period. Thirty-seven Annex I countries and the EU agreed to second-round Kyoto targets. These countries are Australia, all members of the European Union, Belarus, Iceland, Kazakhstan, Norway, Switzerland, and Ukraine.[19] Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine stated that they might withdraw from the Protocol or not put into legal force the Amendment with second round targets.[20] Japan, New Zealand, and Russia participated in Kyoto’s first round but did not take on new targets in the second commitment period. Other developed countries without second-round targets were Canada (which withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol in 2012)[21] and the United States.

All countries that remained parties to the Kyoto Protocol met their first commitment period targets.[22]

National communication

A “National Communication” is a type of report submitted by the countries that have ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).[23] Developed countries are required to submit National Communications every four years and developing countries should do so.[24][25][26] Some Least Developed Countries have not submitted National Communications in the past 5–15 years,[27] largely due to capacity constraints.

National Communication reports are often several hundred pages long and cover a country’s measures to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions as well as a description of its vulnerabilities and impacts from climate change.[28] National Communications are prepared according to guidelines that have been agreed by the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC. The (Intended) Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that form the basis of the Paris Agreement are shorter and less detailed but also follow a standardized structure and are subject to technical review by experts.

Paris Agreement

The parties met in Durban, South Africa in 2011 and expressed “grave concern” that efforts to limit global warming to less than 2 or 1.5 °C, relative to the pre-industrial level, appeared inadequate.[29] They committed to develop an “agreed outcome with legal force under the Convention applicable to all Parties”.[30]

At the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference in Paris[31] the then-196 parties agreed to aim to limit global warming to less than 2 °C, and try to limit the increase to 1.5 °C.[32][18] The Paris Agreement entered into force on 4 November 2016 in those countries that had ratified the Agreement, and other countries had ratified the Agreement since.

Intended Nationally Determined Contributions

At the 19th session of the Conference of the Parties in Warsaw in 2013, the UNFCCC created a mechanism for Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) to be submitted in the run up to the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties in Paris (COP21) in 2015.[33] Countries were given freedom and flexibility to ensure that these climate change mitigation and adaptation plans were nationally appropriate.[34] This flexibility, especially regarding the types of actions to be undertaken, allowed for developing countries to tailor their plans to their specific adaptation and mitigation needs, as well as towards other needs.

In the aftermath of COP21, these INDCs became Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) as each country ratified the Paris Agreement, unless a new NDC was submitted to the UNFCCC at the same time.[35] The 22nd session of the Conference of the Parties (COP22) in Marrakesh focused on these Nationally Determined Contributions and their implementation, after the Paris Agreement entered into force on 4 November 2016.[36]

The Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) created a guide for NDC implementation, for the use of decision makers in Less Developed Countries. In this guide, CDKN identified a series of common challenges countries face in NDC implementation, including how to:

- build awareness of the need for, and benefits of, action among stakeholders, including key government ministries;

- mainstream and integrate climate change into national planning and development processes;

- strengthen the links between subnational and national government plans on climate change;

- build capacity to analyse, develop and implement climate policy;

- establish a mandate for coordinating actions around NDCs and driving their implementation; and

- address resource constraints for developing and implementing climate change policy.[37]

Further commitments

In addition to the Kyoto Protocol (and its amendment) and the Paris Agreement, parties to the Convention have agreed to further commitments during UNFCCC Conferences of the Parties. These include the Bali Action Plan (2007),[38] the Copenhagen Accord (2009),[39] the Cancún agreements (2010),[40] and the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (2012).[41]

- Bali Action Plan

As part of the Bali Action Plan, adopted in 2007, all developed country Parties have agreed to “quantified emission limitation and reduction objectives, while ensuring the comparability of efforts among them, taking into account differences in their national circumstances.”[42] Developing country Parties agreed to “[nationally] appropriate mitigation actions context of sustainable development, supported and enabled by technology, financing and capacity-building, in a measurable, reportable and verifiable manner.”[42] 42 developed countries have submitted mitigation targets to the UNFCCC secretariat,[43] as have 57 developing countries and the African Group (a group of countries within the UN).[44]

- Copenhagen Accord and Cancún agreements

As part of the 2009 Copenhagen negotiations, a number of countries produced the Copenhagen Accord.[39] The Accord states that global warming should be limited to below 2.0 °C (3.6 °F).[39] The Accord does not specify what the baseline is for these temperature targets (e.g., relative to pre-industrial or 1990 temperatures). According to the UNFCCC, these targets are relative to pre-industrial temperatures.[45]

114 countries agreed to the Accord.[39] The UNFCCC secretariat notes that “Some Parties … stated in their communications to the secretariat specific understandings on the nature of the Accord and related matters, based on which they have agreed to [the Accord].” The Accord was not formally adopted by the Conference of the Parties. Instead, the COP “took note of the Copenhagen Accord.”[39]

As part of the Accord, 17 developed country Parties and the EU-27 submitted mitigation targets,[46] as did 45 developing country Parties.[47] Some developing country Parties noted the need for international support in their plans.

As part of the Cancún agreements, developed and developing countries submitted mitigation plans to the UNFCCC.[48][49] These plans were compiled with those made as part of the Bali Action Plan.

- UN Race-to-Zero Emissions Breakthroughs

At the 2021 annual meeting UNFCCC launched the ‘UN Race-to-Zero Emissions Breakthroughs’. The aim of the campaign is to transform 20 sectors of the economy in order to achieve zero greenhouse gas emissions. At least 20% of each sector should take specific measures, and 10 sectors should be transformed before COP 26 in Glasgow. According to the organizers, 20% is a tipping point, after which the whole sector begins to irreversibly change.[50][51]

- Developing countries

At Berlin,[52] Cancún,[53] and Durban,[54] the development needs of developing country parties were reiterated. For example, the Durban Platform reaffirms that:[54]

[…] social and economic development and poverty eradication are the first and overriding priorities of developing country Parties, and that a low-emission development strategy is central to sustainable development, and that the share of global emissions originating in developing countries will grow to meet their social and development needs.

Parties

As of 2022, the UNFCCC has 198 parties including all United Nations member states, United Nations General Assembly observers the State of Palestine and the Holy See, UN non-member states Niue and the Cook Islands, and the supranational union European Union.[55][56]

Classification of Parties and their commitments

Parties to the UNFCCC are classified as:

- Annex I: There are 43 Parties to the UNFCCC listed in Annex I of the convention, including the European Union.[57] These Parties are classified as industrialized (developed) countries and “economies in transition” (EITs).[58] The 14 EITs are the former centrally-planned (Soviet) economies of Russia and Eastern Europe.[59]

- Annex II: Of the Parties listed in Annex I of the convention, 24 are also listed in Annex II of the convention, including the European Union.[60] These Parties are made up of members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): these Parties consist of the members of the OECD in 1992, minus Turkey, plus the EU. Annex II Parties are required to provide financial and technical support to the EITs and developing countries to assist them in reducing their greenhouse gas emissions (climate change mitigation) and manage the impacts of climate change (climate change adaptation).[58]

- Least-developed countries (LDCs): 49 Parties are LDCs, and are given special status under the treaty in view of their limited capacity to adapt to the effects of climate change.[58]

- Non-Annex I: Parties to the UNFCCC not listed in Annex I of the convention are mostly low-income[61] developing countries.[58] Developing countries may volunteer to become Annex I countries when they are sufficiently developed.

List of parties

Annex I countries

There are 43 Annex I Parties including the European Union.[57] These countries are classified as industrialized countries and economies in transition.[58] Of these, 24 are Annex II Parties, including the European Union,[60] and 14 are Economies in Transition.[59]

- Notes

Conferences of the Parties (CoP)

The United Nations Climate Change Conference are yearly conferences held in the framework of the UNFCCC. They serve as the formal meeting of the UNFCCC Parties (Conferences of the Parties) (COP) to assess progress in dealing with climate change, and beginning in the mid-1990s, to negotiate the Kyoto Protocol to establish legally binding obligations for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.[8] Since 2005 the Conferences also served as the Meetings of Parties of the Kyoto Protocol (CMP) and since 2016 the Conferences also serve as Meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA).

The first conference (COP1) was held in 1995 in Berlin. The 3rd conference (COP3) was held in Kyoto and resulted in the Kyoto protocol, which was amended during the 2012 Doha Conference (COP18, CMP 8). The COP21 (CMP11) conference was held in Paris and resulted in adoption of the Paris Agreement. The COP26 (CMA3) was held in Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom. COP28 is taking place at the United Arab Emirates and Sultan al-Jaber has been nominated by the ruler to lead the same.[63]

Subsidiary bodies

A subsidiary body is a committee that assists the Conference of the Parties. Subsidiary bodies include:[64]

- Permanents:

- The Subsidiary Body of Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) is established by Article 9 of the convention to provide the Conference of the Parties and, as appropriate, its other subsidiary bodies with timely information and advice on scientific and technological matters relating to the convention. It serves as a link between information and assessments provided by expert sources (such as the IPCC) and the COP, which focuses on setting policy.

- The Subsidiary Body of Implementation (SBI) is established by Article 10 of the convention to assist the Conference of the Parties in the assessment and review of the effective implementation of the convention. It makes recommendations on policy and implementation issues to the COP and, if requested, to other bodies.

- Temporary:

- Ad hoc Group on Article 13 (AG13), active from 1995 to 1998;

- Ad hoc Group on the Berlin Mandate (AGBM), active from 1995 to 1997;

- Ad Hoc Working Group on Further Commitments for Annex I Parties under the Kyoto Protocol (AWG-KP), established in 2005 by the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol to consider further commitments of industrialized countries under the Kyoto Protocol for the period beyond 2012; it concluded its work in 2012 when the CMP adopted the Doha Amendment;[65]

- Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action (AWG-LCA), established in Bali in 2007 to conduct negotiations on a strengthened international deal on climate change;

- Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP), established at COP 17 in Durban in 2011 “to develop a protocol, another legal instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force under the Convention applicable to all Parties.”[66] The ADP concluded its work in Paris on 5 December 2015.[67]

Secretariat

The work under the UNFCCC is facilitated by a secretariat in Bonn, Germany. The secretariat is established under Article 8 of the Convention and headed by the Executive Secretary. Patricia Espinosa was appointed Executive Secretary on 18 May 2016 by United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and took office on 18 July 2016.[68] Espinosa retired on 16 July 2022.[68] UN Under Secretary General Ibrahim Thiaw served as the acting Executive Secretary in the interim.[69] On 15 August 2022, Secretary-General António Guterres appointed former Grenadian climate minister Simon Stiell as Executive Secretary, replacing Espinosa.[70]

Former executive secretaries are:

| List of Executive Secretaries of the UNFCCC Sources:[69][71] |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sr | Executive Secretary | Country | Tenure | Other offices held | ||

| From | To | |||||

| 1 | Michael Zammit Cutajar | 1995 | 2002 | |||

| 2 | Joke Waller-Hunter | 2002 | 2005 | |||

| 3 | Yvo de Boer | 10 August 2006 | 1 July 2010 | |||

| 4 | Christiana Figueres | 1 July 2010 | 18 July 2016 | |||

| 5 | Patricia Espinosa | 18 July 2016 | 16 July 2022 | |||

| Acting | Ibrahim Thiaw | 17 July 2022[72] | 14 August 2022 | |||

| 6 | Simon Stiell | 15 August 2022[70][73][74] | Incumbent | |||

Commentaries and analysis

Interpreting article 2

The ultimate objective of the Framework Convention is “stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic [i.e., human-caused] interference with the climate system”.[1] Article 2 of the convention says this “should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner”.[1]

Obviously, that is either no longer a consideration of this body, or they have failed miserably at attaining it. We know that our food production and food supply is already in grave danger and the economic development of the all nations is in the crapper!!

-

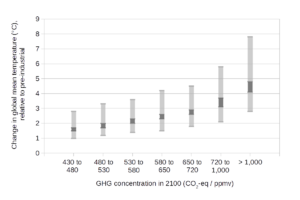

Climate change mitigation scenarios: projected global greenhouse gas emissions, years 2000 to 2100

-

Climate change mitigation scenarios: projected changes in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, years 2000 to 2100

-

Climate change mitigation scenarios: projected global mean temperature, years 2000 to 2100

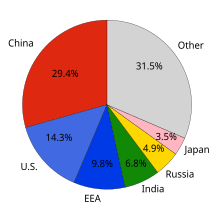

To stabilize atmospheric GHG concentrations, global anthropogenic GHG (GreenHouse Gasses) emissions would need to peak then decline (see climate change mitigation).[75] Lower stabilization levels would require emissions to peak and decline earlier compared to higher stabilization levels.[75] The graph above shows projected changes in annual global GHG emissions (measured in CO2-equivalents) for various stabilization scenarios. The other two graphs show the associated changes in atmospheric GHG concentrations (in CO2-equivalents) and global mean temperature for these scenarios. Lower stabilization levels are associated with lower magnitudes of global warming compared to higher stabilization levels.[75]

There is uncertainty over how GHG concentrations and global temperatures will change in response to anthropogenic emissions (see climate change feedback and climate sensitivity).[76] The graph opposite shows global temperature changes in the year 2100 for a range of emission scenarios, including uncertainty estimates.

- Dangerous anthropogenic interference

There are a range of views over what level of climate change is dangerous.[77] Scientific analysis can provide information on the risks of climate change, but deciding which risks are dangerous requires value judgements.[78]

The global warming that has already occurred poses a risk to some human and natural systems (e.g., coral reefs).[79] Higher magnitudes of global warming will generally increase the risk of negative impacts.[80] According to Field et al. (2014),[80] climate change risks are “considerable” with 1 to 2 °C of global warming, relative to pre-industrial levels. 4 °C warming would lead to significantly increased risks, with potential impacts including widespread loss of biodiversity and reduced global and regional food security.[80]

Climate change policies may lead to costs that are relevant to the article 2.[78] For example, more stringent policies to control GHG emissions may reduce the risk of more severe climate change, but may also be more expensive to implement.[80][81][82]

- Projections

There is considerable uncertainty over future changes in anthropogenic GHG emissions, atmospheric GHG concentrations, and associated climate change.[76][83][84] Without mitigation policies, increased energy demand and extensive use of fossil fuels[85] could lead to global warming (in 2100) of 3.7 to 4.8 °C relative to pre-industrial levels (2.5 to 7.8 °C including climate uncertainty).[86]

To have a likely chance of limiting global warming (in 2100) to below 2 °C, GHG concentrations would need to be limited to around 450 ppm CO2-eq.[87] The current trajectory of global emissions does not appear to be consistent with limiting global warming to below 1.5 or 2 °C.[88]

Precautionary principle

In decision making, the precautionary principle is considered when possibly dangerous, irreversible, or catastrophic events are identified, but scientific evaluation of the potential damage is not sufficiently certain (Toth et al., 2001, pp. 655–656).[89] The precautionary principle implies an emphasis on the need to prevent such adverse effects.

Uncertainty is associated with each link of the causal chain of climate change. For example, future GHG emissions are uncertain, as are climate change damages. However, following the precautionary principle, uncertainty is not a reason for inaction, and this is acknowledged in Article 3.3 of the UNFCCC (Toth et al., 2001, p. 656).[89]

Criticisms of the UNFCCC process

The overall umbrella and processes of the UNFCCC and the adopted Kyoto Protocol have been criticized by some as not having achieved their stated goals of reducing the emission of carbon dioxide (the primary driver of rising global temperatures of the 21st century).[9] At a speech given at his alma mater, Todd Stern—the US Climate Change envoy—expressed the challenges with the UNFCCC process as follows: “Climate change is not a conventional environmental issue … It implicates virtually every aspect of a state’s economy, so it makes countries nervous about growth and development. This is an economic issue every bit as it is an environmental one.” He went on to explain that the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is a multilateral body concerned with climate change and can be an inefficient system for enacting international policy. Because the framework system includes over 190 countries and because negotiations are governed by consensus, small groups of countries can often block progress.[90]

The failure to achieve meaningful progress and reach effective CO2-reducing policy treaties among the parties over the past eighteen years has driven some countries like the United States to hold back from ratifying the UNFCCC’s most important agreement—the Kyoto Protocol—in large part because the treaty did not cover developing countries which now include the largest CO2 emitters. However, this failed to take into account both the historical responsibility for climate change since industrialisation, which is a contentious issue in the talks, and also responsibility for emissions from consumption and importation of goods.[91] It has also led Canada to withdraw from the Kyoto Protocol in 2011 out of a wish not to make its citizens pay penalties that would result in wealth transfers out of Canada.[92] Both the US and Canada are looking at internal Voluntary Emissions Reduction schemes to curb carbon dioxide emissions outside the Kyoto Protocol.[93]

The perceived lack of progress has also led some countries to seek and focus on alternative high-value activities like the creation of the Climate and Clean Air Coalition to Reduce Short-Lived Climate Pollutants which seeks to regulate short-lived pollutants such as methane, black carbon and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which together are believed to account for up to 1/3 of current global warming but whose regulation is not as fraught with wide economic impacts and opposition.[94]

In 2010, Japan stated that it will not sign up to a second Kyoto term, because it would impose restrictions on it not faced by its main economic competitors, China, India and Indonesia.[95] A similar indication was given by the Prime Minister of New Zealand in November 2012.[96] At the 2012 conference, last-minute objections at the conference by Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan were ignored by the governing officials, and they have indicated that they will likely withdraw or not ratify the treaty.[97] These defections place additional pressures on the UNFCCC process that is seen by some as cumbersome and expensive: in the UK alone, the climate change department has taken over 3,000 flights in two years at a cost of over £1,300,000 (British pounds sterling).[98]

Further, the UNFCCC (mainly during the Kyoto protocol) failed to facilitate the transfer of environmentally sound technologies (SETs) which are mechanisms used to decrease the vulnerability of the human race against the unfavourable effects of climate change. One of the more widely used of these being renewable energy sources. The UNFCCC created the body “technology mechanism” who would distribute these resources to developing countries; however this distribution was too moderate and, coupled with the failings of the first commitment[99] period of the Kyoto protocol, led to low ratification numbers for the second commitment (resulting in it not going ahead).

Before the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, National Geographic magazine added to the criticism, writing: “Since 1992, when the world’s nations agreed at Rio de Janeiro to avoid ‘dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system,’ they’ve met 20 times without moving the needle on carbon emissions. In that interval we’ve added almost as much carbon to the atmosphere as we did in the previous century.”[100]

Benchmarking

Benchmarking is the setting of a policy target based on some frame of reference.[101] An example of benchmarking is the UNFCCC’s original target of Annex I Parties limiting their greenhouse gas emissions at 1990 levels by 2000. Goldemberg et al. (1996)[102] commented on the economic implications of this target. Although the target applies equally to all Annex I Parties, the economic costs of meeting the target would likely vary between Parties. For example, countries with initially high levels of energy efficiency might find it more costly to meet the target than countries with lower levels of energy efficiency. From this perspective, the UNFCCC target could be viewed as inequitable, i.e., unfair.

Benchmarking has also been discussed in relation to the first-round emissions targets specified in the Kyoto Protocol (see views on the Kyoto Protocol and Kyoto Protocol and government action).

International trade

Academics and environmentalists criticize article 3(5) of the convention, which states that any climate measures that would restrict international trade should be avoided.[citation needed]

Engagement of civil society

In 2014, The UN with Peru and France created the Global Climate Action Portal NAZCA for writing and checking all the climate commitments.[103][104]

Civil Society Observers under the UNFCCC have organized themselves in loose groups, covering about 90% of all admitted organisations. Some groups remain outside these broad groupings, such as faith groups or national parliamentarians.[105]

An overview is given in the table below:[105]

| Name | Abbreviation | Admitted since |

|---|---|---|

| Business and industry NGOs | BINGO | 1992 |

| Environmental NGOs | ENGO | 1992 |

| Local government and municipal authorities | LGMA | COP1 (1995) |

| Indigenous peoples organizations | IPO | COP7 (2001) |

| Research and independent NGOs | RINGO | COP9 (2003) |

| Trade union NGOs | TUNGO | Before COP 14 (2008) |

| Women and gender | WGC | Shortly before COP17 (2011) |

| Youth NGOs | YOUNGO Archived 19 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine | Shortly before COP17 (2011) |

| Farmers | Farmers | (2014) |

UNFCCC secretariat also recognizes the following groups as informal NGO groups (2016):[106]

| Name | Abbreviation |

|---|---|

| Faith Based Organizations | FBOs |

| Education and Capacity Building and Outreach NGOs | ECONG |

| Parliamentarians |

spacer

This is why Charles III will be known as the 1st climate king, experts say

Charles has been vocal about his passion for sustainability for decades.

King Charles III wants to protect the planet for future generations — a passion he highlighted during the six decades he spent as monarch-in-waiting.

Now it is abundantly clear what Charles wishes to accomplish during his time as monarch, experts say.

“His mother took the crown at a very young age and nobody knew what she stood for,” David Victor, a professor of innovation and public policy at the University of California at San Diego and author of “Fixing the Climate: Strategies for an Uncertain World,” told ABC News. “Whereas he is taking the crown very late in age and everybody knows what he stands for.“

MORE: Death of Queen Elizabeth II prompts debate about the monarchy’s legacy, future

Charles’ efforts have also included championing initiatives to engage businesses around conversations about sustainability and, most importantly, focusing on trying to find solutions that work, according to Bob Ward, policy and communications director at The London School of Economics and Political Science’s Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

“He’s used his position to raise awareness — not just in the U.K. but around the world,” Ward said. “He has, for a long, long time, probably earlier than many politicians, understood the importance of this issue.”

Due to his “extensive background” on environment and sustainability issues, there is “no doubt” that the depth of Charles’ commitment to it runs deep, Alden Meyer, a senior associate working on U.S. and international climate policy and politics at E3G, a London-based think tank on climate policy, told ABC News.

Here is why experts say Charles III will be known as the United Kingdom’s first “climate king”:

Charles has a long history of environmental activism

King Charles III began his environmental activism long before words like “sustainable,” “organic” and “grass-fed” were trendy. In fact, much of the British public viewed his passion for the environment as an “oddity” when it first began, Ward said.

“He was talking about this before it was cool,” Meyer said.

One of the “most interesting” tidbits about Charles’ history of engagement with environmental issues is the push he has made around landscapes, especially surrounding managing landscapes and the role of natural, working land has in absorbing carbon, as well as the role architecture plays in absorbing carbon, Victor said.

Charles’ gardens at Highgrove House, the estate in Gloucestershire he purchased in 1980, are a prime example of his early commitment to sustainability. The grounds feature organically maintained gardens, including a kitchen garden, formal garden and wild garden, the latter which serves as a sustainable habitat for birds and wildlife. Solar panels have also been installed, and waste from the house is filtered through a natural sewage system.

By doing this, the king has moved the conversation surrounding sustainability from focusing solely on industrial emissions to how climate change is also embedded into the landscape, Victor said.

In 1989, Charles wrote the book “A Vision of Britain,” in which he argued that the traditional methods of architecture and aesthetics used in the past in Britain should be used more in the future. That vision resulted in an experimental planned community of 3,500 in Dorset, a county on England’s southwest coast, which implemented traditional approaches and techniques honed over thousands of years in the U.K.

The community, named Poundbury, generally uses the development principles of New Urbanism, a framework that emphasizes walkability in cities. Sustainable methods of transportation, such as walking, biking and public transit, are key to incorporating a sustainable lifestyle, climate experts say.

Charles’ commitment to mitigating climate change has even been evident in recent years and months. He has been especially vocal about the climate crisis in the past five years.

In June 2021, before the G-7 summit commenced in Cornwall, Charles urged businesses to tackle the climate emergency alongside government, adding that unlocking cash within the private sector was the key to winning the battle against global warming and biodiversity loss.

Charles remained outspoken in the lead-up to COP26, the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference that began converging in Glasgow, Scotland, in October.

Weeks before the conference began, Charles implored world leaders to do more than “just talk” at the climate summit, which was billed by environmentalists as one of the last chances to change the trajectory of global warming.

From Prince George’s Wood, an arboretum Charles has created in the gardens of his house on the Balmoral estate in Aberdeenshire, the-then Prince of Wales said it had taken “far too long” for the world to make the climate crisis a priority, adding that following his example of going meat- and fish-free two days a week and dairy-free one day a week could “reduce a lot of the pressure” on the collective carbon footprint.

The Prince of Wales Foundation and other entities and charities that Charles has been involved with have been deeply engaged, particularly in reaching out to the business community in the private sector and finance and encouraging them to step up their game, Meyer said.

Charles also attended a series of events at COP26, as did Queen Elizabeth II and Prince William and his wife, Catherine, then the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge.

Charles’ passion even extends past the Earth’s own atmosphere. In July, the king-in-waiting called for an “Astro Carta” to establish sustainable space exploration, working with the Space Directorate of the U.K.’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) to reduce emissions for future missions. That same month, he again urged for climate action as Europe experienced record-breaking heat waves, in which he described the temperatures as “alarming.”

The conservation legacy runs in the royal family

Charles inherited his passion for conservation from his parents, and he has now passed it to his son and heir, Prince William, the new Prince of Wales, Ward said.

One of the most noted characteristics of Queen Elizabeth II was her love of dogs and horses, and her husband, Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, was a “very strong voice” for wildlife, even serving as patron for the World Wildlife Fund for much of his time as a working royal. In the 1950s, Charles and Princess Anne were photographed while meeting famed biologist and natural historian David Attenborough, and Charles has maintained the relationship with the former BBC broadcaster — even awarding the 96-year-old his second knighthood earlier this year.

The notion of being environmentally conscious is a very “British trait,” Ward said, adding that former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was the first major world leader to talk about climate change at the United Nations in 1989.

While the queen was also interested in these issues, Meyer does not believe her ambition matches the extent of her son, a monarch who is now “deeply engaged, committed and knowledgable,” Meyer said.

“Charles is coming from a family that is, has expressed, you know, and use their voice frequently about environmental issues,” Ward said. “And his views on the environment are very much shared by wider society in the U.K.”

When the U.K. hosted COP26, the queen urged world leaders attending the summit to “rise above the politics of the moment” to find solutions to mitigate climate change.

Charles seems to have passed down his enthusiasm for the environment to Prince William. As the new Prince of Wales, William is currently head of the Earthshot Prize, which aims to promote impactful approaches to the world’s most pressing environmental challenges, and is currently a WildAid ambassador for sharks, rhinos and elephants, of which he has been especially vocal in his efforts to protect the species from extinction.

“Charles has created a legacy within his own family,” Ward said.

The sentiment even extended to the queen’s death. After some of the thousands of mourners began to leave Paddington Bears and marmalade sandwiches in honor of the skit the queen filmed for the Platinum Jubilee in June, the Royal Parks issued a statement requesting that well-wishers only leave organic or compostable material, as well as flowers sans plastic wrap, in “the interests of sustainability.”

“We would prefer visitors not to bring non-floral objects/artefacts such as teddy bears or balloons,” the statement read.

The king’s future influence will likely be a bit quieter

As Prince of Wales, Charles was permitted to be more vocal about his ardor for protecting the environment. But now that he is king, Charles may be required to rein in his enthusiasm, the experts said.

“I think he will be careful about what he says in public,” Ward said. “He will know that there are limits on what he could and should be saying.”

Charles will likely have the most impact within his own realms, especially since, unlike in the U.S., every major business in the United Kingdom already knows they need to be “serious” about pushing sustainable practices, Victor said.

“He’s already pushing an open door,” Victor said.

Still, there’s a possibility that prompts and nudges from Charles to do more for the environment will not be fruitful.

“The king doesn’t actually have a huge amount of impact on the economy,” Victor said. “And, if anything, the monarchy has been paying very special attention to not overreaching, overstepping its role [of] what is normally considered the function of government.”

The institution’s tendency to take a step back and remain silent may be reinforced for Charles, who ascended the throne as a less popular monarch than his mother, the experts said.

Still, Charles will have the ears of major players who can make a difference, such as corporate leaders and top members of the government, such as Prime Minister Liz Truss, with whom he will conduct weekly audiences.

“That’s an opportunity for the monarch to ask questions about government policy, make recommendations, do a little advocacy privately,” Meyer said. “But that’s very different than the kind of public role that he’s had in his foundations.”

In addition, Ward said he expects that Charles will continue to deliver subtle messages supporting environmentalism in his annual televised Christmas speech.

“I would imagine that King Charles will continue that tradition, where he will talk about issues that are of importance,” Ward said.

The king has inherited a nation in transition

The United Kingdom got a new prime minister and monarch in a matter of days.

Charles will now be working with Truss, who does not have a great track record of promoting environmentally friendly policies, the experts said.

“You’ve got a new prime minister coming in who is probably less committed and passionate about this issue than the outgoing prime minister,” Meyer said, adding that while Boris Johnson was not deeply passionate about environmental issues when he first took office, that changed as the need for developed countries to whittle their emissions down to net-zero became clear.

In addition, the U.K. is still in the middle of Brexit and disconnecting from the European economy — at the same time, the West is disconnecting from the Chinese economy, Victor said.

This could be a hindrance to the climate fight, as having access to a global economy will be necessary to implement the best and lowest-cost technologies into industries, Victor added.

“What’s going to be particularly interesting is what Charles says and does with regard to Britain’s place in the world concerning its interaction with the economies of other countries in the role of Britain and cooperating with other countries,” Victor said.

Charles will need to strike the right tone

The king has a long-standing appreciation of the importance of environmental issues and has a deeper connection to the environment than most, but that experience may be connected to his privilege, the experts said.

Charles will need to toe the line as he encourages the masses to live sustainably, especially since most are not afforded the wealth, influence and privilege to do so, they added.

While Charles was a pioneer in organic farming, he had the means to completely transform the overgrown land he purchased at Highgrove and employ top architects and gardeners to help him see his vision through, Victor said. In addition, the average person cannot transform their Aston Martin to run on biodiesel, let alone even own a luxury vehicle.

“That’s something you can do if you have a lot of land and a lot of money,” Victor said. “The bigger challenge for deep decarbonization and for managing landscape is what you do with the large fraction of the public that can’t afford to eat that way.”

Striking the right tone will be especially crucial as the U.K. reels from the energy crisis that resulted from the aftereffects of eliminating coal consumption combined with its dependence on Russian oil. Analysts are expecting a tough winter for the majority of residents in the United Kingdom as gas prices continue to skyrocket, sending the costs to heat homes even higher, Meyer said.

Still, Victor believes the world will underestimate Charles and his ability to encourage advances in the climate fight.

“It’s very hard to judge a public figure, especially a public figure who is an institution that requires you to be quiet,” he added.

ABC News’ Tracy Wholf contributed to this report.

spacer

When King Charles III was a young prince, in the early nineteen-fifties, he sometimes propelled a ride-on toy around Windsor Castle, one of several royal residences where he spent his childhood. Pedalling furiously, he hardly registered the spectacular works from the Royal Collection on the walls. “It’s just a background,” Charles later recalled. His attention was arrested, however, by one unusual portrait: of King Charles I, displayed in the Queen’s Ballroom. The sensitive and reflective prince, who was born in 1948 and who by the age of seven was being tutored by a governess in the history of the nation—and of his historic family—was fascinated by the painting. “King Charles lived for me in that room in the castle,” he later said.

Titled “Charles I in Three Positions,” and painted in the sixteen-thirties by Van Dyck, the work offers three representations of the elegant monarch: in profile, facing forward, and in three-quarter view. With his long, flowing hair cut fashionably shorter on one side, he is depicted wearing three distinct robes and three ornate lace collars, and he is accessorized with the blue sash of the Order of the Garter, Britain’s oldest chivalric order. The painting was made about a decade after Charles’s accession, in 1625, and was used as a blueprint for a marble bust by Bernini. Charles I—who was devout, reserved, and convinced of his right to absolute power as the head of the Stuart dynasty—was a great patron of the arts. Among other extravagant commissions, he asked Rubens to decorate the ceiling of the grand Banqueting House, in London’s Palace of Whitehall, with canvases illustrating heavenly approval of James I, his father.

The triple portrait may have commanded the young Prince Charles’s attention because of his royal precursor’s lurid fate: Charles I had the distinction of being the only British king to be tried for treason and executed. He was sentenced to death by a High Court of Justice, set up by a Parliament that he had antagonized by dissolving it repeatedly, which helped bring about devastating years of civil war. On November 18, 1648—nearly three hundred years to the day before the birth of Charles, on November 14th—the King’s opponents argued in the House of Commons that “the Person of the King may and shall be proceeded against in a way of justice for the blood spilt.” After a brief trial, the royal head was publicly severed from the royal shoulders, on a scaffold outside the Banqueting House. The monarchy was abolished a week later, the office of the king declared by the Commons as “unnecessary, burdensome, and dangerous to the liberty, safety, and public interest of the people of this nation.” The Puritan republic lasted only eleven years, after which Parliament voted to install on the throne Charles II, the licentious eldest surviving son of the deposed king. But the powers of the restored monarchy were more limited, and by the late seventeenth century the Glorious Revolution had affirmed the idea that British kings and queens retain their crowns only by the consent of the people.

Van Dyck’s triple portrait is, on its own terms, irresistibly suggestive of the psychological complexity of its royal subject. The king in profile has a heavy brow: he appears thoughtful, even melancholy. The three-quarter king, who wears a dandyish pearl earring, has a faraway look in his eye, and a faint smile plays at the corner of his mouth. The forward-facing king appears supremely self-assured, even arrogant. For the young Charles, the principal fascination of the triple portrait may well have been in its proto-photographic quality—a high-class mug shot of a king ultimately judged to be a criminal. But the portrait might also have suggested to the Prince—who would already have learned that he was destined to become Britain’s third King Charles—that to be a monarch is to be a divided self, in a role that is sometimes precariously split among the constitutional, the institutional, and the personal. Being a king is not just one thing.

After Queen Elizabeth II died, at the age of ninety-six, on September 8, 2022, King Charles III delivered a televised speech—his first public address as monarch. His eyes were rheumy and his complexion florid; his hair, thoroughly silver, was brushed as carefully as it had been in 1953 when, as a fidgety four-year-old, he had endured his mother’s almost three-hour-long coronation service, in Westminster Abbey. “Queen Elizabeth’s was a life well lived, a promise with destiny kept,” he said, in a speech that was praised for its emotionality and steadiness. He also proclaimed, “That promise of lifelong service I renew to you all today.”

The Queen’s astonishing longevity in the role of monarch—she lasted for seventy years, a full seven years longer than Queen Victoria—has a corollary in Charles’s own, less triumphant statistical attributes. He is the oldest British monarch to have ascended to the throne, at seventy-three. (His wife, Camilla, who has been given the title of Queen Consort, is a year older.) Charles, whose coronation is scheduled for May 6th, has been the longest-serving Prince of Wales, a title bestowed on him by the Queen when he was an introverted nine-year-old. Already the Duke of Cornwall, a title that he had received upon his mother’s accession, he learned of this latest honor while at prep school. Invited to watch the televised announcement in his headmaster’s study, Charles was mortified by the congratulations of his fellow-pupils. It was, he later said, the moment when he first saw clearly the “awful truth” of his singular fate.

Has it really been so awful? Perhaps. Unlike the former Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Charles didn’t dream as a child of being “World King,” and he has long made it clear that he considers his birthright a burden. “Nobody knows what utter hell it is to be the Prince of Wales,” he has reportedly complained. Although Charles is literally the most entitled man in the land, a royal can feel like an anachronism, and he apparently feels a kinship with certain other Britons who are marginalized. Paddy Harverson, the Prince’s former communications secretary, says that Charles has a particular fondness for the sheep farmers of remote Cumbria, “because they are about the most forgotten community you can find.”

Tom Parker Bowles—Charles’s godson, and later his stepson—grew up thinking that Charles’s name was Sir, because that’s all anyone ever called him. Yet Sir suffers from a peculiar aristocratic version of impostor syndrome. He is wise enough to know that, in almost any room he enters other than one occupied by members of his family, he is likely to be the only person present whose power and influence derive entirely from his birth. Indeed, if Charles checked his privilege, there would be nothing left of him—just a crumpled pile of ermine and velvet, and a faint whiff of Eau Sauvage.

Harverson says that Charles’s self-consciousness about being a royal drove him to become “the hardest-working man I know,” adding, “First thing in the morning, he does his exercises and has his abstemious breakfast, working on his papers over breakfast. Before he goes to bed, any time up to midnight, he’ll be doing more work—and all the points in between.”

At the beginning, this work was rather nebulous. The position of Prince of Wales has no specified constitutional purpose or duties, as Charles discovered as a young man, when he instructed his staff to research precedents and possibilities, and found no guidance. During his twenties, he spent several years in the Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy. In a speech that he delivered at his alma mater, the University of Cambridge, on the eve of his thirtieth birthday, he admitted, “My great problem in life is that I do not really know what my role in life is.” He added, “Somehow I must find one.” Charles, who subsequently told an interviewer that it would be “criminally negligent” of him to do nothing, has started more than a dozen charities, including the Prince’s Trust, and has served as the patron of scores of others. He has spoken out for decades on causes about which he is passionate, from organic farming and town planning to education and alternative medicine, leveraging his fame in a way that is constitutionally denied to the monarch, who must remain staunchly apolitical. (Luckily for the Queen, her chief passion was horses.) A few years ago, he urgently summoned the composer Andrew Lloyd Webber to his office to present an idea. “He was worried about . . . the fact that there wasn’t enough access for young people to go and learn how to play the church organ,” Lloyd Webber told the Washington _Post._ In April, 2021, Charles marked International Organ Day with a message to the Royal College of Organists, urging its members to secure the future viability of what, as he reminded them, Mozart had described as the “King of Instruments.”

Charles could have spent his anticipatory decades like some former heirs to the throne: devoting himself to hunting and wenching. To be fair, he’s done a bit of both. He was an avid foxhunter until the activity was outlawed, in 2005; he characterized it as reflecting “man’s ancient, and, indeed, romantic relationship with dogs and horses.” As for other romantic relationships: long before Prince Harry spilled his guts, in a tell-all memoir, “Spare,” about losing his virginity in a field behind a pub, Charles’s sanctioned biographer, Jonathan Dimbleby, wrote humidly in 1994 of his subject’s deflowering at Cambridge by an early paramour, described as a “young South American” who had “instructed an innocent Prince in the consummation of physical love.”

But, in general, Charles has conducted his role as monarch-in-waiting with laudable earnestness. One need not go so far as to say that he has the makings of a saint—as the Reverend Harry Williams, a former dean of the chapel at Trinity College, Cambridge, once did—to believe that the country could have done much worse. Kings can be dreadful. Until the birth of Prince William, in 1982, the world was just one helicopter accident or foxhunting tumble away from the prospect of King Andrew I.

People who know Charles sometimes describe him as a cuckoo in the royal nest—someone quite unlike the other members of his family. He inherited neither the stoicism of his mother nor the emotional imperviousness of his father, Prince Philip. Charles was born into a family so formal and hidebound that, when the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth ordained that her children would no longer be expected to bow or curtsy when entering her presence, the move was seen as wildly progressive. Whereas his bold younger sister, Anne, used to march up and down in front of the sentries at Buckingham Palace in order to oblige them to present arms, as if darting before automatic sliding doors in a hotel lobby, Charles cringed at his own authority. As a young man, he considered himself “a ‘single’ person that prefers to be alone and is happy just with hills or trees as companions.” Later, Charles was indelibly defined in contrast with his first wife, Princess Diana, who was “the great, emotional, open, sensitive one,” as Catherine Mayer, one of Charles’s more subtle recent biographers, observes. “The irony is that he was seen as this stone creature, but in fact he’s far more like her than like other members of his own family, in many ways.”

Charles readily prioritizes intuition over analytic thought, especially if it’s his own intuition that’s being prioritized. “He doesn’t allow debate,” Tom Bower, the author of a mostly-warts biography, says. “It’s his droit du seigneur—he doesn’t like contradiction, whether within his causes or his office.” He’s not exactly an intellectual, but he is a reader, especially of history, and compared with his parents and his siblings he’s a raving brainbox. A first-gen university student who benefitted from a bespoke affirmative-action program—no other first-year student at Trinity College had his own set of rooms, and a detective on hand—Charles is a passionate defender of the cultural canon. He knows by heart long passages of Shakespeare, which, as he told Dimbleby, can “in moments of stress or danger or misery” give “enormous comfort and encouragement.” (It’s not hard to see how certain stylings of the Bard—“This royal throne of Kings, this sceptred isle”—might buck up a demoralized monarch-to-be.)

Like the works of Shakespeare, or church-organ music, the monarchy is something that once was inarguably valued but now must make a case for its relevance. It is no secret that Charles believes the modern world to have gone to hell, in any number of ways; although such thinking is not unusual for a septuagenarian, few individuals can be as invested in the matter as Charles, whose whole gig is to be a symbol of tradition. Twenty years ago, a letter that he had written emerged in the course of an employment lawsuit brought by a former employee at Clarence House, his royal residence in London, and his words betrayed a similarly intemperate view of contemporary culture. “What is wrong with people nowadays?” he wrote. “Why do they all seem to think they are qualified to do things far above their capabilities?” He went on to blame “a child-centered education system which tells people they can become pop stars, high court judges, or brilliant TV presenters or infinitely more competent heads of state without ever putting in the necessary work or having the natural ability.” He concluded with a grand flourish: “It is a result of social utopianism which believes humanity can be genetically engineered to contradict the lessons of history.” Charles did not dilate further on what those lessons might be. But it’s safe to assume that they’d justify one of the most notorious compromises struck between the claims of the genetic and of the social: the existence of a hereditary sovereign within a constitutional monarchy.

“This is a call to revolution”—so reads the grabby first sentence of “Harmony: A New Way of Looking at Our World,” a book that Charles published in 2010. The future king was quick to clarify that the sort of revolution he was calling for was not the monarch-deposing kind. He went on, “The Earth is under threat. It cannot cope with all that we demand of it. It is losing its balance and we humans are causing this to happen.” We must, he wrote, embark on a “Sustainability Revolution.”

Charles has long held strong views on environmental matters: in the seventies, he warned of the dangers of pollution, and by the early eighties he had become an outspoken advocate of organic farming and a critic of industrial agribusiness. At the time, he was often dismissed as a crank. A 1984 article in the Daily Mirror imagined the future king sitting “cross-legged on the throne wearing a kaftan and eating muesli”—little realizing how mainstream these activities would become, except for the throne-sitting. In a 1982 speech, Charles lamented, “Perhaps we just have to accept that it is God’s will that the unorthodox individual is doomed to years of frustration, ridicule, and failure in order to act out his role in the scheme of things, until his day arrives, and mankind is ready to receive his message.”

Ian Skelly, one of Charles’s two co-authors on “Harmony” and a writer who has helped him with speeches, says, “A lot of people have quietly realized that he was right all along about a lot of this. There’s always a lot of people who did take him seriously, but the vast majority thought he was up there in the trees with the fairies.” Charles’s criticisms of factory farming and of the use of artificial pesticides have become widespread, though the sustainability practices reportedly carried out at Highgrove, his beloved country residence in Gloucestershire, are beyond the capacities of most farmers: according to Tom Bower, a team of four gardeners lie face down on a trailer as it is dragged by a slow-moving Land Rover, so that they can pull up weeds.

Charles has also been unafraid to criticize powerful bodies of experts such as the British Medical Association, whose ire he earned forty years ago by unfavorably contrasting contemporary medicine with ancient folk healing, in particular homeopathy, and by comparing the modern medical establishment to “the celebrated Tower of Pisa—slightly off balance.” (A doctor with the B.M.A. subsequently declared homeopathy to be “nonsense on stilts.”) He is notoriously hostile to modern architecture, and, in a vitriolic 1987 speech to a gathering of distinguished British planners and designers, he proclaimed, “You have, ladies and gentlemen, to give this much to the Luftwaffe—when it knocked down our buildings, it didn’t replace them with anything more offensive than rubble. We did that.” Charles’s remarks bring to mind the Internet era’s Godwin’s law, which holds that once an argument escalates online someone inevitably invokes the Nazis; usually, though, the comparison is not in the Nazis’ favor. Once, while on a tour of a fifty-story office building that César Pelli had designed for the Canary Wharf area of London, Charles querulously asked, “Why does it need to be quite so high?” This remark prompted another member of the tour—the art historian Roy Strong—to observe that, if people had thought that way in the Middle Ages, there would be no spire atop Salisbury Cathedral. Charles made no reply—but, then again, we know how he feels about the Tower of Pisa.

Such rampant position-taking was often understood to be evidence of a butterfly mind, flitting from one issue to another. As Dimbleby, his biographer, put it, “He approached new ideas like a swimmer diving among rocks: sometimes he discovered a pearl and sometimes he banged himself on the head.” The press portrayed Charles as “the meddling prince,” suggesting that his interventions—including unsolicited memos to government ministers—both undermined professional expertise and ran counter to his future role. The King now has a weekly audience with the Prime Minister, during which he can quietly offer advice. (“Back again? Dear, oh dear” was Charles’s rather ungracious greeting to the hapless Liz Truss in October.) But the British monarch is, by convention, obliged to sign into law whatever the government puts in front of him, whether he agrees with it or not.

Charles is easy to condemn as out of touch. Bower’s book devilishly recounts an occasion when the Prince’s kitchen staff left him some cold cuts for a late supper. He shrieked with horror and called for Camilla’s aid—apparently, it was his first encounter with cling film. Having spent a lifetime being characterized by the press as a fogy, an oddball, or a nostalgist, Charles had an opportunity, in “Harmony,” to present a self-portrait, and a self-defense. In the book, he seeks to demonstrate how his apparently disparate concerns—architecture, farming, climate change—are in fact linked. Each of them, he argues, is an expression of the absence of “harmony”—a concept that he defines as “the active state of balance which is just as vital to the health of the natural world as it is for human society.” In many ways, the book is profoundly conservative: an idyllic image of crofters’ huts in the Yorkshire Dales is paired with a dystopian shot of tower blocks and industrial chimneys in Dundee, Scotland, as if the former could perform the same function as the latter. But “Harmony” is also surprisingly radical in its rejection of the inevitability of consumer capitalism. “Real wealth is good land, pristine forests, clean rivers, healthy animals, vibrant communities, nourishing food and human creativity,” Charles writes. “But the money managers have turned land, forests, rivers, animals and human creativity into commodities to be bought and sold.”

Ian Skelly says of Charles, “He’s met every expert you can imagine, and is deeply informed about a massive range of subjects.” Skelly notes, “He says he can’t remember anything, but don’t talk to him about sheep! Don’t talk to him about flora and fauna.” Charles’s concern and commitment are transparently heartfelt, even if his solutions can seem arcane: it was recently announced that his vintage Aston Martin has been converted to run on surplus wine and leftover cheese whey.

Charles is known to have some frugal habits—he gets his clothes patched rather than having them replaced. Still, in other respects, his life is one of excess. The Guardian recently estimated that the King’s privately held assets, which include property, jewelry, horses, and vintage cars, have a collective value of nearly two and a quarter billion dollars. (In an indignant response, the Palace said that the figures were “a highly creative mix of speculation, assumption and inaccuracy,” but declined to offer an accurate tally.) And though only the most uncompromising of republicans would deny that a king needs a castle, or two, Charles has access to more palatial homes than the most advantageously equipped plutocrats. His estates range from Windsor Castle to Sandringham House and Balmoral Castle—and those are just the ones that he’s recently taken over from the Queen. The monarch does not pay an inheritance tax. For many Britons, it can feel strange to be lectured on the need to reduce consumption by someone whose family has arrogated so much to itself.

“Harmony” is perhaps most valuable for revealing how Charles would prefer to be understood: as a philosopher-king who, unlike a politician vulnerable to the whims of an electorate, is in a position to take the long view. “ ‘Harmony’ was seen by some people as an environmental book, but it’s not just that,” Tony Juniper, an environmentalist and the book’s other co-author, says. “It’s a philosophy book about the place of people in the universe.” Charles describes ancient practices—the geometrical patterns of sacred architecture; farming techniques that respected rather than depleted the soil—that underscore how humanity once saw itself as integrated with Nature rather than elevated above her. (For the King, Nature is capitalized and female.) Khaled Azzam, the director of the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts, in London, which since 2005 has taught subjects as diverse as illuminated-manuscript-making and the principles of Islamic architecture, says, “His Majesty has always been interested in humanity as a whole, not humanity in its fragmented form.”

As Charles sees it, human civilization made its first errant turn in the seventeenth century, with the onset of the scientific revolution and the subsequent prioritizing of rationalism and secularism over other systems of thought. He writes reverently of Indigenous cultures, noting that the Kogi people, of present-day Colombia, see themselves as an “Elder Brother” created “to protect the Earth, whom they inevitably call the Mother”; they must also contend with “a Younger Brother, a wayward creature . . . whose ways must be curbed before it is too late.” The Charles of “Harmony” is given to pronouncements like this: “The Enlightenment caused wonderful things to happen, but I do wish that the champions of mechanistic science would be more prepared than they are to accept that it also brought downsides.”

It does not seem coincidental that, in Charles’s time line of history, things started to go downhill around the period when people began chopping off the heads of monarchs. Jonathan Healey, a professor of history at Oxford University and the author of “The Blazing World: A New History of Revolutionary England, 1603-1689,” says that, in the tumultuous years of the early seventeenth century, when religious authority was being questioned, Charles I was also invested in the concept of harmony—which, as Healey points out, is another word for “order.” “It hinges on everyone knowing their place,” he explains. “The peasants don’t question who is in charge, and they are happy. They are fed and they are looked after by the aristocracy, but they don’t criticize them.”

Unlike Charles I, Charles III has shown a passionate concern for members of society who lack opportunities for education or professional advancement. More than a million young people have received financial support from the Prince’s Trust to, say, start a business or further their education. But believing that everyone deserves an equal opportunity to make the best of her life is not the same as believing that everyone can—or should—rise to the top. In “Harmony,” Charles suggests that the happiest, most just, and most sustainable framework for humans is built on traditional values of community, with individuals enjoying the satisfactions of labor and the consolations of nature within a sturdy social structure. He writes most glowingly of the sorts of rural communities that would have been common in the time of Charles I: sheep farmers who produce mutton, “a once commonly eaten meat that has a really delicious flavor and texture,” belong to a “harmonious pattern of existence and production that not only sustains many of the landscapes that help to define our identity and nurture our very souls, but also sustains entire communities of people.”

The kinds of pre-industrial societies that Charles admires were headed by a lord of the manor, who, in turn, deferred to a king. Although it might not be entirely fair to describe Charles as feudalism-curious, his world view does appear to incorporate an implicit defense of his monarchical position. As Charles seems to see it, a king should be a benign convener at the head of a natural hierarchy. “Studying the properties of harmony and understanding more clearly how it works at all levels of creation reveals a crucial, timeless principle: that no one part can grow well and true without it relating to—and being in accordance with—the well-being of the whole,” he writes in his book.

At a gathering a few years ago, Charles was introduced to Thomas Kaplan, an American businessman and the founder of Panthera, a nonprofit devoted to the preservation of lions, tigers, and other big cats. Kaplan says, “I realized I had a few minutes, max, to have his attention, and I put it to him very simply—I told him that you have to see cats as an umbrella species for vast ecosystems. Cats need two things to thrive: they need land to roam, and they need food. If you have the flora and fauna to support the very top of the food chain, by definition you have a thriving ecosystem.” Several months later, Kaplan learned that Charles had essentially repeated his case on behalf of big cats while on a visit to government officials in South America. Kaplan was impressed: “It told me that, when he is touched by something, it registers, and that he has a remarkable capacity to apply it.” But it’s no surprise that Kaplan’s pitch would resonate with Charles. The lion is the king of the jungle. When the King is thriving, it follows that all is also well in his dominion.

While Charles struggled to find his individual purpose as Prince of Wales, he was obliged to carry out his dynastic purpose by producing an heir. His marriage to Diana, Princess of Wales, was no more a love match than was Charles I’s arranged union, in 1625, with Henrietta Maria, the fifteen-year-old youngest daughter of the late King of France. (In time, they grew closer, partly because of a mutual love of art. It can happen.) Diana had initially seemed to share at least some of Charles’s enthusiasms: she submitted with apparent contentment to his love of the outdoors, even allowing herself to be taught to fish. And she promptly produced two sons, William and Harry. But when the marriage was still young it became clear that she had no interest in Charles’s devotion to the gardens at Highgrove, and that she was bored by and resentful of the books he read and the friends he kept. Although Charles rekindled an affair with his old girlfriend Camilla Parker Bowles—“Do you seriously expect me to be the first Prince of Wales in history not to have a mistress?” he reportedly once said—he was pained by the catastrophic failure of a marriage that he imagined he could never escape. “How awful incompatibility is,” he wrote to a friend, five years after the wedding. “How dreadfully destructive it can be.”