This is one of the most important posts I have ever done. It serves to connect a lot of the dots. Don’t miss it.

I understand that historically the average person has had a seriously difficult time believing that a small group of people were conspiring against he rest of us. Meeting in remote resorts and makeing decisions on issues that affect us far more than them. But, seriously, with all that has been revealed over the last 50 years… you have to be willfully blind not to recognize this to be true.

We see now that they have deliberately been undermining our national sovereignty through the use of private meetings between wealthy Corporate heads, Royalty, Universities, 501C3 Charities, Philanthropists, private organizations and public leaders who are committing treason selling out their constituents. They have created their own “GLOBAL GOVERNMENT” that does not care at all what happens to the average person.

I am going to show you, in this post, some of those meetings about which you likely have no knowledge. I am also going to present evidence that not only was the sinking of the Costa Concordia connected to the plans of these Oligarchs but a couple other tragedies also under the name Concordia.

|

Meaning “a compact or agreement” is from late 15c. concord (v.) |

| Herzigova. remember the model who christened the Costa Concordia? Herz – we see means heart |

igo, you go – Verbmall – Blogger.comBlogger

Sep 9, 2009 — It comes straight from a Latin word that meant “a turning or whirling around,” which is the sensation experienced even if standing stock still.

|

|

May 23, 2010 — It is suggested the root meaning of vant or vand is vessel

|

spacer

This is another long post, but I promise you it is eyeopening! There is a lot of information, photos and videos. I provide all of it for you. It is not enough for me to just tell you what I discover. It is important for you to see the evidence with your own eyes. I know most people today do not have time to really research and uncover the truth. However, unless you invest in the TRUTH it will always allude you. If you just brush the surface and/or accept things as they are reported, you are living on only a fraction of the information necessary to reach a solid conclusion.

That may be ok when it comes to making simple decisions like what toothpaste to buy or what color you want your new car to be. But, when it comes to decisions that affect your life on earth or worse yet your eternal life to come… you can’t afford to be lazy. The cost is too dear!

Bear with me, and stay to the end. It will be very beneficial. ENJOY!

spacer

Oh, how they love the MOUNTAINS. Did you ever wonder why? Well, wonder NO MORE! By the end of this post, you will KNOW.

Concordia Summit – Wikipedia

Concordia is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. It is best known for its Annual Summit in New York City, which is a global affairs forums that promotes partnering between governments, businesses, and nonprofits to address the world’s most pressing needs.

Concordia was founded in 2011 by Matthew Swift and Nicholas Logothetis. They had been best friends since high school, where they were business partners in a successful food purveyor enterprise.[1][2] Both attended university in Washington, D.C., and both had a background in journalism, media, politics, and international affairs.[3][1][4][5][6] Noting the effectiveness of the formats of the Wall Street Journal CEO Council and the Clinton Global Initiative,[7][2] they founded Concordia as a nonprofit organization that helps develop public-private partnerships (P3s), in the belief that the most effective and sustainable way to find solutions to pressing global issues is through cooperation between the public, private, and nonprofit sectors.[8][1][9]

In light of the 10th anniversary of 9/11, Swift and Logothetis formulated their first concept as “Building Partnerships Against Extremism”,[10] and focused the first Concordia Summit, in September 2011, on combating the root causes of extremism – failing states, poverty, and lack of education – through dialogue and partnering between businesses, governments, and NGOs.[7][1]

Concordia continues to convene a large annual summit each fall in New York City during the week of the United Nations General Assembly, as a gathering place for world leaders, business leaders, innovators, and nonprofit personnel to discuss and foster cross-sector partnership to address the world’s most pressing problems.[3][11][2] Along with these annual summits and additional regional summits, its year-round activities include events programming in diverse areas, targeted social-impact campaigns, and research into public-private partnerships.[12][8]

13 January 2012, the eight-year-old Costa Concordia hit a ROCK and capsized and was grounded near the Isle of Giglio.

spacer

The “Illumined Ones” are always on a quest to ‘ASCEND’ to Godhood.

BUILDING PARTNERSHIPS FOR SOCIAL IMPACT

Concordia is a global convener of heads of state, government officials, C-suite executives, and leaders of nonprofits, think tanks, and foundations to find cross-sector solutions that address the biggest challenges of our time. The Concordia Annual Summit is the largest and most inclusive nonpartisan forum alongside the UN General Assembly, while Concordia also hosts regional summits with a focus on the Americas, United States, Europe, and Africa. Concordia is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit membership organization founded in 2011 by Matthew A. Swift and Nicholas M. Logothetis.

BUILDING PARTNERSHIPS FOR SOCIAL IMPACT

Concordia is a global convener of heads of state, government officials, C-suite executives, and leaders of nonprofits, think tanks, and foundations to find cross-sector solutions that address the biggest challenges of our time. The Concordia Annual Summit is the largest and most inclusive nonpartisan forum alongside the UN General Assembly, while Concordia also hosts regional summits with a focus on the Americas, United States, Europe, and Africa. Concordia is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit membership organization founded in 2011 by Matthew A. Swift and Nicholas M. Logothetis.

Matthew (given name) – WikipediaMatthew is an English language male given name. It ultimately derives from the Hebrew name “מַתִּתְיָהוּ” (Matityahu) which means “Gift of God”. Matthew. Pronunciation. To a pagan would mean gift from the gods or from the heavens.

|

|

Old English, from swīfan to turn; related to Old Norse svifa to rove, Old Frisian swīvia to waver, Old High German sweib a reversal; see swivel

swivel from frequentative form of stem of Old English verb swifan “to move in a course, revolve, sweep” (a class I strong verb), from Proto-Germanic *swif-, swip- (source also of Old Frisian swiva “to be uncertain,” Old Norse svifa “to rove, ramble, drift”), which is perhaps from a PIE root *swei- “to turn, bend, move in a sweeping manner

swiftie (n.) also swifty, 1945, “fast-moving person,” from swift (adj.) + -y (3). As a nickname often ironic. Also from 1945 as “act of deception, trick, sleight” (compare pull a fast one).

|

| Nicholas |

|

Greek: from the status name logothetēs in Byzantium denoting a high ecclesiastical dignitary or for the keeper of the emperor’s seal also the person who composed the emperor’s speeches and wrote his decrees. The term is derived from Greek logos ‘word’ ‘speech’ + thetēs an agent noun from tithēmi ‘to put’. Source: Dictionary of American Family Names 2nd edition, 2022 |

| Wow… that is powerful naming. Very enlightening! Names/Words reveal everything if you find the root! |

Libra Group Names Manos Kouligkas CEO; Elevates George Logothetis to …

| Logothetis is chairman of Concordia’s leadership council; his brother Nick co-founded the summit. George, the London-born heir to his family’s Greek shipping business, runs a global holding company that owns everything from ships to helicopters to hotels all over the world. The company is so impressive that Logothetis, who flies a bit under the radar in American business, made Fortune’s 40 Under 40 list in 2014. Source |

spacer

MARCH 9-10, 2023 (ALREADY PAST)

UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI | MIAMI, FLORIDA

The University of Miami, Concordia’s Principal Programming Partner, will be the official host of the 2023, 2024, and 2025 Concordia Americas Summits. As Concordia’s longest-standing regional initiative, the seventh iteration of the Americas Summit gathered leaders from the public, nonprofit, and private sectors to confront the challenges and opportunities facing the Western Hemisphere, with a particular focus on Latin America. Furthering many of the outcomes and themes from the 2022 Americas Summit, the 2023 Concordia Americas Summit sparked concrete steps rooted in a common bond: the desire to see the hemisphere reach its full potential.

“A city like Miami has experienced tremendous prosperity because we have followed some simple rules. It highlights to me as Mayor that we have a job to do—not just in terms of leadership in this country, but in terms of leadership throughout the world.”

HON. FRANCIS SUAREZ, MAYOR OF THE CITY OF MIAMI

“Sometimes we create this false dichotomy between action at the global level and at the national level. The truth is that everything is both global and local at the same time. You can’t be effective as a national leader if you’re not engaged locally.”

DR. JULIO FRENK, PRESIDENT OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI

ADDITIONAL AMERICAS SUMMIT DATES

- 2024 Americas Summit – March 2024

- 2025 Americas Summit – March 2025

PROGRAMMING THEMES

CULTURAL DIPLOMACY & YOUTH ADVOCACY

In a world fraught with conflict, the value of stable and resilient communities has never been higher. They are built through the active participation of citizens who have a voice in their future. Ensuring that the most disempowered of society, youth, and—in particular—young women are engaged is essential in upholding trusted institutions that respond to the needs of its community. The exchange of a nation’s ideas, language, and art can also be used as tools to articulate its ideas, values and political goals, allowing societies to speak to one another. Can cultural resources be mobilized to unite a divided world? How can cross-sector collaboration place youth advocacy at the center of policy-making decisions?

DEMOCRACY, SECURITY & GEOPOLITICAL RISK

The state of democracy in the Western Hemisphere has been an increasing concern for decades, but never has it been more pertinent than now. Although the region is vastly represented by democracies, threats persist of dictatorships taking over democratic institutions, where socioeconomic inequalities and corruption can exacerbate, resulting in highly-polarized societies. A focus on upholding democratic institutions and maintaining national security will be central to policymakers in achieving a sense of domestic peace around the world. How can cross-sector collaboration bring together divided countries? What role will emerging technology play in the future of national security, and how can it be governed?

ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY

As instances of devastating natural disasters around the world become more and more common, it has become clear we are in the midst of the consequences of decades of exponential industrial growth and unrestricted consumption. In order to preserve our planetary health and create a healthy future for generations to come, urgent action is required. For governments, this requires rebuilding strength in the trust of institutions. For businesses, the warming climate poses operation risks, and whilst it is widely acknowledged that employing sustainable practices will be more profitable to organizations, there remains a disconnect in their implementation. What opportunities exist for businesses in the shift toward environmental and social responsibility? How can we ensure those suffering the most from the impacts of climate change are not left out when investing in its solutions?

FINANCIAL INCLUSION

Within nations and along the Global North/South divide, the existing disparities between ethnicities, socioeconomic status, and gender, when examining access to financial services, have been exacerbated by the global pandemic. This hinders the ability of individuals to generate income, invest, and manage cash flow, and hence is essential to the post-pandemic economic recovery. It is also vital in strengthening democratic institutions, which have been dismantled by a declining trust due to a rise in unemployment and poverty, as well as the rampant spread of mis- and disinformation. At a smaller scale, financial inclusion is also necessary to empower communities, such as by enabling access to education and food. As we strive to build more resilient financial infrastructures, how do we ensure equitable access that retains quality and safety? What doubts remain about the role of technology in closing this gap? What commitments should be made by the private, public, and third sectors in their collaboration?

HEALTH OPPORTUNITIES & CHALLENGES

The events of recent years have redirected unprecedented attention on the need to achieve more resilient healthcare systems. This awareness has also brought a new recognition of long-existing disparities in healthcare around the world along lines of gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and the Global North/South divide. Today, we also know the pandemic had a detrimental impact on global mental health, with long-term consequences requiring immediate action. How do we facilitate innovation to prevent the next pandemic being one of mental health? How can we improve global partnerships for pandemic preparedness? How can we use these lessons to redesign stronger healthcare systems that can reach further? And, how can we rebuild institutional trust to ensure optimal healthcare reaches all members of society, and a sense of confidence in our health future?

INNOVATIVE TECHNOLOGY

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, technological innovations have proven to be critical in the response to global challenges and the capacity of societies to act. Organizations and individuals have had no choice but to digitize in order to survive, making a tech-savvy economy and a hybrid workforce the new norm. This digital transformation has brought solutions to civic society, such as increased social connectivity, revolutionary therapeutics, and sustainable technologies. However, it has also produced a new mode of unchecked dialogue leading to a mis- and disinformation crisis. What is the role of technology in society? How can we better fortify against workplace disruptions and close the gendered and socioeconomic digital skills gap? Can the answer to increasing privacy concerns be found collectively?

REGIONAL INITIATIVES

Concordia’s Regional Initiatives, focused on the United States, Americas, Africa, Europe, and Amazon region, foster communities of private sector, government, and nonprofit leaders to spark dialogue and enable effective partnerships for social impact. Understanding the role regional affairs play in international relations, these initiatives examine the most pressing challenges in a specific area and identify opportunities for meaningful collaboration.

The Concordia Americas Initiative was launched in May 2016, with the inaugural 2016 Concordia Americas Summit in Miami, Florida serving as one of the first international platforms to raise awareness about the Venezuelan humanitarian crisis. Since then, Concordia has brought together world-renowned political leaders, business innovators, and global non-governmental representatives in Bogotá, Colombia to host its flagship regional convening, exploring critical issues facing the Western Hemisphere, with a particular focus on Latin America, through the lens of cross-sector collaboration.

With the inaugural Concordia Europe Summit taking place in Athens, Greece in 2017, the Concordia Europe Initiative provides an international platform through which to elevate action-oriented dialogue around the outlook for Europe as a whole, while also exploring the critical relationship between the European Union and the international community.

CONCORDIA AMAZONAS

Launched at the 2022 Concordia Annual Summit by Former Colombian President Iván Duque, the Concordia Amazonas Initiative raises awareness of the link between the health of the Amazon and the health of the planet, defining the necessary commitments that must be made by the private sector to preserve the rainforest.

Following the 2022 Lexington Summit, the Concordia United States Initiative provides a necessary platform for multi-sector and bipartisan collaboration in order to effectively drive forward innovative solutions to the most pressing issues facing the country.

Officially launched at the 2018 Annual Summit, Concordia Africa is an African-led program that fosters a community of cross-sector leaders to share strategies and priorities for economic growth and lasting prosperity on the African continent. Shaped and driven by local stakeholders, the initiative strives to build sustainable and scalable alliances among the government, private sector, and civil society, in line with Concordia’s broader mission.

CONCORDIA AMERICAS

The unique captivation of Latin America, with its vibrant dynamics but challenging issues, has resonated with the vision of Concordia since its founding in 2011. The region’s critical position on the global stage, and the interconnected nature of its challenges with the success of the Western Hemisphere, aligns with Concordia’s ethos to create an inclusive, collaborative global community. Latin America has remained a focal point for Concordia since 2011, with the evolution of the organization’s on-the-ground work in Colombia resulting in the establishment of the Concordia Americas Initiative.

CONCORDIA AMERICAS EVENTS

Concordia’s initial connection with Latin America began in 2011, when Co-Founders Matthew Swift and Nicholas Logothetis first met Álvaro Uribe Vélez, President of the Republic of Colombia from 2002 until 2010. Iván Duque Márquez, appointed President of the Republic of Colombia in 2018, was working at the Inter-American Development Bank at the time, and advised Matt and Nick to approach Uribe, who was Vice Chairman of the UN investigative committee for the 2010 Gaza flotilla raid. Later that year, President Uribe visited New York City during UNGA week and featured in an interview with MSNBC about the inaugural Concordia Summit (watch here).

In 2012, Concordia was honored to welcome President Uribe to New York City to participate in the 2012 Concordia Annual Summit, where he was interviewed by Matt and Nick and then delivered closing remarks, following a keynote address from President Clinton. That same year, Uribe joined Concordia’s Leadership Council, a powerful roster of former heads of state, leaders of industry, and policy experts with practical experience at every level of government and business.

At the 2015 Annual Summit, Concordia hosted a panel with Andrés Pastrana Arango, Former President of the Republic of Colombia, Jorge Quiroga Ramírez, Former President of the Plurinational State of Bolivia, and Felipe Calderón Hinojosa, Former President of the United Mexican States. The panel, which provided a fascinating insight into how Latin American governments can work with the private sector to overcome political and economic challenges, ended with a standing ovation from the audience in New York City. To read the 2015 Concordia Annual Summit Report, click here.

In May 2016, Concordia hosted its first-ever Summit outside of New York at Miami Dade College in Miami, Florida. Inspired by Dr. Eduardo J. Padrón, Concordia Leadership Council Member and President of Miami Dade College, the 2016 Concordia Americas Summit marked the official launch of the Concordia Americas Initiative. The high-level gathering of over 200 public and private sector leaders addressed the priorities of the region, including democracy, energy, trade, regional security, and corruption through a unique and interactive strategic dialogue format—now one of the drivers behind Concordia’s action-oriented programming. The Summit was chaired by José María Aznar, former President of the Government of Spain and Concordia Leadership Council Member, who inspired a focus on the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela, with programming featuring Venezuelan Human Rights Activist Lilian Tintori. The Summit also marked the first meeting of Tintori and Luis Almagro Lemes, Secretary General of the Organization of American States. The 2016 Concordia Americas Summit Report can be found here.

A driving force behind the introduction of the Americas Initiative was María Paula Correa, Concordia’s Former Senior Director of Strategic Engagement. María Paula was instrumental in building Concordia’s Americas presence through the organization’s convenings in New York and Miami, and by leveraging the expertise of Leadership Council Members.

2016 AMERICAS SUMMIT IN MIAMI

Concordia prioritized collaboration across the Western Hemisphere as a focal point of its 2017 programming and beyond, with the 2017 Concordia Americas Summit in Bogotá, Colombia serving as the organization’s first-ever international convening. Sponsored fully by Colombian companies, the Concordia Americas Summit brought together the past three presidents—then President Juan Manuel Santos Calderón, as well as former Presidents Álvaro Uribe Vélez and Andrés Pastrana Arango. Welcoming three heads of state representing varying viewpoints on often polarizing issues marked a defining moment in the country’s history. The Summit was co-chaired by Amb. Juan Carlos Pinzón, Ambassador of Colombia to the United States, and Alfonso Gómez Palacio, President of Telefónica Colombia. It also saw the beginning of a partnership with the Instituto de Ciencia Política Hernán Echavarría Olózaga (ICP), a leading Colombian political think tank. To read the 2017 Americas Report, click here.

Following the Summit, Concordia partnered with Conservación Internacional for its inaugural Day of Engagement. Concordia Members had the opportunity to see firsthand how art, culture, and the environment are interwoven into the Colombian peace process, connecting real partnerships to the Summit conversations.

2017 CONCORDIA AMERICAS SUMMIT IN BOGOTÁ

When thinking about Concordia’s return to Colombia in 2018, the need to host a meaningful and relevant convening during an election year was of central importance. At the beginning of the year, Concordia led a series of roundtable discussions examining the issues to be faced by the incoming government. These discussions laid the foundations for Concordia to host the official RCN/NTN24 Presidential Debate (watch here) in April. The debate, which featured the leading six presidential candidates of Colombia’s 2018 elections, was followed by a panel of nationally- and internationally-recognized experts to react to the answers given.

The 2018 Concordia Americas Summit, which took place in July in Bogotá, provided the first major international convening following the country’s presidential elections. In partnership with ICP, Fenalco, Noticias RCN, and NTN24, the Summit convened international thought leaders, politicians, business executives, and non-governmental representatives, to foster constructive dialogue and drive lasting, collaborative solutions to the challenges facing Colombia and Latin America as a whole. The Summit featured President Santos, President-elect Duque, Vice President-elect Ramírez (now President and Vice President, respectively), and former Vice President of the United States Joe Biden, among many Colombian private sector leaders. On the Concordia stage, President Duque announced the appointment of Dr. Guillermo Botero, previously President of Fenalco, as his Minister of Defense.

Following the 2018 Concordia Americas Summit, Concordia partnered with Fundación Biblioseo for an inspiring, insightful, and interactive Day of Engagement. Located in the outskirts of Bogota, in Ciudad Bolivar, Biblioseo’s mission is to educate youth aged 8-19 as social leaders and entrepreneurs so that they are stimulated to devise creative solutions to the challenges facing their environments.

2018 CONCORDIA AMERICAS SUMMIT IN BOGOTA

In February 2019, Concordia hosted President Iván Duque Márquez for dinner to mark the occasion of his visit to Washington, D.C. The intimate dinner provided an opportunity to hear first-hand from the President himself on not just the progress underway in Colombia, but also on the pressing nature of Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis. The dinner also served to announce the opening of Concordia’s first international office in Bogotá, Colombia.

2019 CONCORDIA AMERICAS SUMMIT IN BOGOTA

Building on many of the themes from the 2019 Americas Summit, the 2019 Annual Summit explored both the challenges and opportunities facing Latin America and examined its position in the global arena. Conversations examined strategies for effective humanitarian intervention in Venezuela, the impact of a U.S.-China trade agreement on developing economies, and reincorporating coca farmers into the Colombian market, among much more.

CONCORDIA AMERICA ORGANIZATIONS

spacer

CONCORDIA EUROPE

Europe is entering uncharted territory. Against a backdrop of unprecedented political development, the potential for opportunity is unparalleled. A hub of activity, innovation, and development, the continent is poised to capitalize on this evolving landscape.

CONCORDIA EUROPE EVENTS

Concordia launched its Europe Initiative in 2017, with the inaugural Concordia Europe Summit in Athens, Greece, taking place at a pivotal time for the continent following significant shifts in regional leadership. The Summit, which explored the role of partnerships in preserving a modern-day union, quelling the refugee crisis, and reigniting regional economic growth, highlighted Greece as one of the fundamental foundations of democracy in the world. It featured a keynote address from U.S. Vice President Joe Biden, who discussed the importance of the transatlantic partnership between Europe and the U.S. in addressing economic challenges and enhancing security.

Given the current state of international affairs, Europe remains at the forefront of many of the most pressing global issues, among them the changing landscape of global commerce, addressing mass migration, achieving the SDGs by 2030, and adapting to technological developments. The region has therefore remained a focal point of Concordia’s programming since the inaugural Europe Summit in 2017. The Concordia Annual Summit has heard from European leaders such as Tony Blair, Former Prime Minister of the UK, Alexis Tsipras, Former Prime Minister of Greece, and Lt. Gen. Christopher Cavoli, Commanding General of the United States Army Europe, among many other key European figures.

The 2019 Concordia Europe – AmChamSpain Summit, held in Madrid, Spain in June 2019, provided an international platform to elevate action-oriented dialogue for both Spain and Europe as a whole, while also exploring the critical relationship between the European Union and the international community.

Concordia will return to Madrid to host the 2023 Europe Summit on June 15-16. Through a new and innovative format for Concordia, this one-and-a-half day event will bring together 75 decision makers for a set of high-level closed-door conversations centered on the theme of Democracy, Security & Geopolitical Risk, with a focus on cyber and energy security and diplomatic tools. Through a Concilium format, key leaders will be positioned in front of an intimate, dynamic audience, with the ultimate aim to foster honest and transparent interaction between the public and private sectors. While conversations will be off the record, participants will have the opportunity to share their perspectives with select reporters in dedicated press breakouts and interviews. Following the 2023 Europe Summit, Concordia will present key recommendations to Spanish and EU leadership as Spain assumes the Presidency of the Council of the European Union on July 1, 2023. Learn more here.

CONCORDIA EUROPE SPEAKERS

CONCORDIA EUROPE ORGANIZATIONS

spacer

CONCORDIA AMAZONAS

Launched at the 2022 Concordia Annual Summit by Former Colombian President Iván Duque, the Concordia Amazonas Initiative raises awareness of the link between the health of the Amazon and the health of the planet, defining the necessary commitments that must be made by the private sector to preserve the rainforest.

2023 CONCORDIA AMAZONAS SUMMIT

JULY 26-30, 2023

ECUADOR

spacer

Launched at the 2022 Concordia Annual Summit by Former Colombian President Iván Duque, the Concordia Amazon Initiative aims to raise awareness of the link between the health of the Amazon and the health of the planet, defining the necessary commitments that must be made by the private sector to preserve the rainforest.

The Initiative’s first iteration will consist of a high-level strategic convening in the Amazon in 2023. This gathering will bring together leaders from the private and public sectors in the form of a four day retreat to celebrate the natural diversity and importance of the Amazon and to forge partnerships around innovative and scalable ideas to protect and renew the ecosystem.

Exploring themes such as indigenous culture, climate and environmental sustainability, research and scientific progress, and other critical topics linked to the Amazon, the Initiative will provide an opportunity for attendees to directly connect with each other and the rainforest itself. With its action-oriented focus, participants will establish and build interventions that will play a pivotal role in any climate action policy framework.

To learn more about how to attend, email membership@concordia.net.

PROGRAMMING THEMES

CULTURAL DIPLOMACY & YOUTH ADVOCACY

Conversations on Cultural Diplomacy & Youth Advocacy will focus on the critical role of indigenous communities in preserving the Amazon Rainforest, and the need to protect their human rights and support their social progress. Subtopics include: indigenous conservation methods; indigenous medical pathways, and scaling indigenous entrepreneurship.

ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY

Conversations on Environmental Sustainability will convene public and private sector experts to discuss the creation of innovative, scalable market-driven nature based solutions to catalyze and direct capital to benefit the Amazon region across communities while exploring ways to make it sustainable to preserve the environment. Subtopics include: reforestation; biodiversity; mobilizing climate finance, and the role of the energy industry.

HEALTH OPPORTUNITIES & CHALLENGES

Conversations on Health Opportunities & Challenges will highlight the importance of the Amazon as a natural resource in disease treatment and prevention. Conversations will also focus on the intersection of scaling of innovative technologies and science, indigenous medicinal pathways, and market-driven nature based solutions in the Amazon Rainforest to overcome global health challenges.

PROGRAMMING PARTNER

CONCORDIA UNITED STATES

Following the 2022 Lexington Summit, the Concordia United States Initiative provides a necessary platform for multi-sector and bipartisan collaboration in order to effectively drive forward innovative solutions to the most pressing issues facing the country.

CONCORDIA UNITED STATES EVENTS

spacer

CONCORDIA AFRICA

A continent rich with unparalleled diversity, unprecedented dynamism, and continuous growth, Africa presents a wealth of opportunity. As the continent undergoes a period of rapid demographic expansion, Africa’s position on the global stage is becoming of paramount importance, but global efforts must be undertaken to ensure that African leadership is placed at the forefront of this progress.

By providing an international platform through which to elevate African voices and priorities on a global scale, the Concordia Africa Initiative puts Africa in the driver’s seat and brings African voices to global discussions. Organically cultivating a community-led initiative underscored by African stakeholders, Concordia’s focus is on enhancing the scope for partnership development and exploring opportunities for innovation on the continent, while ultimately showing that African perspectives are integral to an international dialogue about the continent’s future.

CONCORDIA AFRICA EVENTS

The Concordia Africa Initiative was officially launched at the 2018 Annual Summit, with addresses from two major African heads of state: President Nana Akufo-Addo of Ghana and President Paul Kagame of Rwanda. That same year, Concordia appointed two remarkable African leaders as the recipients of the 2018 Leadership Award: Her Excellency Monica Geingos, First Lady of Namibia, and Strive Masiyiwa, Founder & Executive Chairman of Econet Wireless.

In February 2019, Concordia hosted its 2019 Africa Initiative in London (report available here), which fostered a community of cross-sector leaders to share strategies and priorities for economic growth and lasting prosperity on the African continent. The Initiative focused on three key issue areas: youth employment & entrepreneurship; financial inclusion & technology; and, Asian-African ties in investment, trade & infrastructure.

“I WAS DELIGHTED TO ADDRESS THE INAUGURAL CONCORDIA SUMMIT AFRICA INITIATIVE IN LONDON. THE CONCORDIA AFRICA INITIATIVE PROVIDES A PLATFORM FOR CROSS-SECTOR LEADERS TO SHARE THEIR PRIORITIES FOR ECONOMIC GROWTH ON THE AFRICAN CONTINENT AND TO IDENTIFY OPPORTUNITIES FOR COLLABORATION. I JOINED NOELLA COURSARIS MUSUNKA TO DISCUSS MOVING AWAY FROM THE ‘AID NARRATIVE’ AND TOWARDS AFRICAN-LED PHILANTHROPY AND SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITY COLLABORATION.”H.E. TOYIN SARAKI, FOUNDER & PRESIDENT OF WELLBEING FOUNDATION AND CONCORDIA LEADERSHIP COUNCIL MEMBER

The 2019 Annual Summit built on these conversations and themes, hearing from H.E. Prof. Benedict Oramah, President & Chairman of the Board of Directors at the African Export-Import Bank, Noëlla Coursaris Musunka, Founder & CEO of Malaika, H.E. Fayez al-Sarraj, Prime Minister of the Government of the National Accord of Libya, Eddie Mandhry, Director for Africa at Yale University, and Vivian Onano, Youth Representative for the Global Education Monitoring Report at UNESCO and Founder & Director of the Leading Light Initiative, among others.

A crucial milestone in the creation of Concordia Africa was the appointment of H.E. Olusegun Obasanjo, Former President of Nigeria, to the Concordia Leadership Council in August 2018 (the full announcement can be found here). Serving as President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria from 1999 to 2007, and Chairperson of the African Union from July 2004 to January 2006, President Obasanjo provides unparalleled insight into the political landscape both in Nigeria and West Africa as a whole. As the first Nigerian leader to hand power over to a democratically-elected president, he has played a critical, historic role in shaping the country’s political dynamics, and his steadfast commitment to political activism provides tremendous value to the development of Concordia Africa.

In April 2019, Concordia welcomed H.E. Toyin Saraki, Founder & President of The Wellbeing Foundation Africa, to its Leadership Council (the full announcement can be found here). In a conversation titled African-Led Philanthropy: Recasting the Aid-Dependent Narrative at the 2019 Africa Initiative, Mrs Saraki shared her insight into the ways in which African philanthropists and corporate foundations can advance meaningful innovations to create social impact across the continent.

Concordia is proud to name Union Maritime as the Founding Sponsor of Concordia Africa. A London-based owner and operator of chemical tankers focused on clean petroleum products in West Africa as well as internationally, a key focus area for Union Maritime is its educational maritime program with African seafaring nations, such as Nigeria. With Africa yielding vast potential in terms of partnerships for social impact, the collaboration between Concordia and Union Maritime is engaging African stakeholders across a wide range of industries, particularly financial services, in order to identify investment strategies that generate positive impact.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NEW YORK — Today marks day two of the Concordia Summit, Concordia’s annual signature event taking place alongside the United Nations General Assembly

.

Check out the agenda and watch live here:

spacer

Transformer la vision en impact: Annonce des prix du annuel 2017 de Concordia…

turning Vision into Impact Announcement of the 2017 Annual Awards of Concordia

spacer

Concordia Europe Summit in Athens

6 months planning

3 days set up

2 days event play

70 persons production team

800 attendees

80 leaders hosted

INTERNATIONAL LEADERS

- Concordia

- Hilton Athens

- Conferences

- 6-7 June 2017

- #Concordia17

We undertook the challenge to organize and coordinate the summit’s production, meeting all the needs of this high-level institution. By developing an artistic approach that captured the aesthetics of Concordia, we designed and implemented the branding and all relative materials, using all of Hilton Athens Conference Rooms.

Unlike Everest and the eight other highest. 418 IMDb 68 1 h 37 min 2013.

Web Pakistani mountaineer Naila Kiani seen holding Pakistans flag at the top of K2.

The summit k2. The story of the deadliest day on the worlds most dangerous mountain when 11 climbers mysteriously perished on K2.

The summit k2. The story of the deadliest day on the worlds most dangerous mountain when 11 climbers mysteriously perished on K2.

K2 in Pakistan is the second-highest peak in the world and remains the only summit over 8000 metres known as the death zone to never have been successfully reached. A team of 10 Nepali climbers reached the 28251-foot summit of K2 the worlds second-highest mountain on Saturday January 16th according to several (witnessses).

The Summit K2 is slightly shorter than Everest but more dangerous to mountaineers because it is more difficult to climb and has notoriously bad weather.

Within two years Naila Kiani has summited five 8000m peaks including Everest K2 Annapurna and Gasherbrum I and II. K2 8611 meters 28251 feet or Chogori is the worlds second highest mountain after Everest 8048 meters.

Instagramnaila_kiani Pakistani mountaineer Naila Kiani on Sunday reached the top of K2.

A Rare Photo Of The First Rays Of Sunrise Hit K2 Summit From Concordia Places To See Rare Photos Natural Landmarks

Climbing K2 In The Himalayas Mountain Climbing Climbing Rock Climbing

K2 Elevation The Second Highest Mountain In The World K2 Mountain Pakistan Travel Mountaineering

Explore Baltoro and The Karakoram Mountains of Pakistan in K2 Concordia Trek

K2 Concordia trek is in the Karakoram mountain range of Gilgit Baltistan, Pakistan. K2 (8611m), the second-highest mountain in the world, is also known as the savage mountain of the Karakoram.

| Karakoram is a Turkic term meaning black gravel. The Central Asian traders originally applied the name to the Karakoram Pass. Source |

|

KARAKORAM Definition & Usage Examples Dictionary.com

Karakoram · Also called Mustagh. a mountain range in NW India, in N Kashmir. Highest peak, K2, 28,250 feet (8,611 meters). · |

The Muztagh – Travel The HimalayasMuztagh is made up of two words : Muz/ Buz which means Ice and Tagh/Dagh which means Mountain. So it means Ice Mountain which is similar to the word Himalayas which gets its from Sanskrit words Him meaning Snow and Alaya which means home.Jan 18, 2019 |

| Karakorum (Khalkha Mongolian: Хархорум, Kharkhorum; Mongolian script:ᠬᠠᠷᠠᠬᠣᠷᠣᠮ, Qaraqorum; Chinese: 哈拉和林) was the capital of the Mongol Empire between 1235 and 1260 and of the Northern Yuan dynasty in the 14–15th centuries. Its ruins lie in the northwestern corner of the Övörkhangai Province of modern-day Mongolia, near the present town of Kharkhorin and adjacent to the Erdene Zuu Monastery, which is likely the oldest surviving Buddhist monastery in Mongolia. They are in the upper part of the World Heritage Site Orkhon Valley. SOURCE |

Trekking on Baltoro and Godwin-Austin Glaciers to the foothills of this magnificent mountain and Concordia is an absolute classic trek. Concordia is home to the four highest 8000-meter mountains in the world. For its unique location, Concordia is known as the heart of the Karakoram mountain range and earned the nickname “The Throne Room of the Mountain Gods”. On the K2 Concordia trek, you will see the famous Trango Towers, Paiju Peak, Muztagh Tower, Gasherbrum I-II, Gilkey Memorial, Broad Peak, and K2 Basecamp.

K2 Concordia trek begins from Islamabad, the purpose-built capital city of Pakistan. Arrive at Islamabad Airport, where you will be picked up by our representative and transferred to your hotel in Islamabad. Night stay in Islamabad, and the next morning take a spectacular mountain view flight from Islamabad to Skardu. You will see K2, Nanga Parbat, and other famous Karakoram peaks from the aeroplane.

The following day, you will continue your K2 Concordia trek on Baltoro glacier to the Urdukas camp (3,900 meters). Urdukas Campsite is beautifully placed a hundred meters above Baltoro Glaciers, built by the men of Abruzzi during their K2 Expedition in 1909. Now you are getting closer to your ultimate destination Concordia and K2 basecamp in the heart of the Karakoram mountain range.

Wake up with a spectacular view of Gasherbrum IV, which stands at the head of Baltoro Glacier like a beacon guiding you to Concordia. After a full day of trekking, you will finally arrive at Concordia (4,500 meters), the junction point of Baltoro and Godwin-Austen Glaciers. The combination of Baltoro and Godwin-Austin Glaciers is a large piece of ice outside the Polar region. Galen Rowell has described Concordia as the heart of the Karakoram and the Throne room of the mountain gods in his book.

| Gasherbrum IV – surveyed as K3, is the 17th highest mountain on Earth and 6th highest in Pakistan |

From Concordia, you will have a closeup view of K2 (8,611 meters), Broad Peak (8,051 meters), Gasherbrum I-II (8,035 meters), and many other famous Karakoram peaks. Enjoy a breathtaking sunset view over these Karakoram giants and the sensational environment of Concordia.

Please have a look at our videos about this trek on YouTube. The videos are from or August-September 2020 trekking groups. The links are below.

K2 Concordia Trek, on Trango Adventure’s YouTube channel.

sp

Concordia & Beyond in The Karakoram.

Concordia is in the Karakoram mountain range of Pakistan. It is a wider area where glaciers coming down from K2 meet those from the Gasherbrums and Chogolisa. Sir Martin Conway, the famous explorer and alpinist, placed the name Concordia. It is undoubtedly one of the most spectacular places on the planet, and here you can stand within 24 kilometres of no fewer than four eight-thousanders and ten of the world’s thirty highest peaks! All trekking groups camp here at approximately 4500 metres on a moraine ridge surrounded by jagged peaks, including Gasherbrum IV, Mitre Peak, Chogolisa, Crystal Peak, Marble Peak, Baltoro Kangri, Broad Peak and K2. The best view of K2 is from Concordia and beyond.

acer

24 HOURS IN HELL: How 11 mountain climbers died in one day on K2, the world’s most dangerous mountain

Julie Gerstein May 30, 2019, 8:24 AM CDT

On August 1, 2008 (August is the 8th month, 8/1/28 or European 1/8/28 or 1828.), a group of 25 mountain climbers attempted to summit K2. Located on the border between Pakistan and China, K2 is widely believed to be one of the most dangerous mountains in the world.

From the start, the group encountered several problems, including a late start and a lack of climbing supplies.

They’re called the 8000ers — an elite group of climbers who have managed to ascend the tallest and most dangerous peaks in the world — peaks with an altitude of over 8,000 meters, or 26,246 feet.

This past week, several would-be 8000ers have died attempting to climb the highest of these vaunted peaks — Mount Everest. In all, 11 people have died on the mountain since May 21 while climbing in Everest’s notorious Death Zone — the part of the climb that takes place at 26,000 feet and above. Lack of oxygen at that altitude, according to one climber, can feel like “running on a treadmill and breathing through a straw.”

Overcrowding has led to long wait times for climbers to summit and climbers have suffered deadly altitude sickness while waiting to ascend.

But Everest is far from the deadliest mountain. Though around 800 feet shorter than Everest, K2, on the border between China and Pakistan, has the highest ratio of deaths to climbs.

Located at the border between China and Pakistan, K2 is around 800 feet shorter than Everest, but professional climbers consider the ascent much more difficult. Nearly 80 people have died while climbing K2 and it’s considered one of the most grueling climbs in the world. And while nearly 4,000 people have attempted Everest, only 300 have tried to climb K2.

K2’s climbing season is typically between June and August. Extreme weather makes it impossible to climb in all but the warmest temperatures.

In 2008, nearly 200 climbers from around the world arrived at K2’s base camp to attempt the climb. Each group intended to go up separately, spacing out their ascents in order to prevent traffic jams on the route.

But bad weather kept climbers from reaching the summit during June and July. A series of snowstorms made it impossible to climb K2. Climbers spent the summer months acclimatizing and preparing to head up when the weather cleared.

On August 1, a group of 25 climbers from the US, France, Pakistan, Italy, Serbia, The Netherlands, and South Korea — along with their Sherpas and high-altitude porters — began the ascent from Camp 4. They’d spent the previous days climbing up the camp, located at around 7,800 meters (25,000 feet), and set off to complete the final leg of the climb.

Though each group spoke their own language and had made separate preparations for the summit, they came together to tackle the final leg.

Or at least that was the plan.

From the start, there were problems. Bad planning, a lack of communication, and poor conditions endangered them all.

The climbers were being led by a nine-person “trailbreaking group” made up of members from various climbing teams who were responsible for the fixing ropes along the course that would make it possible to safely summit.

But they got a late start on the trail. They also failed to bring enough rope to properly prepare the Bottleneck, a narrow rocky pathway with steep gullies, widely considered to be the most harrowing part of the climb. A serac — a block of glacial ice — hangs over the Bottleneck, threatening to fall on climbers at any moment. As Norwegian climber Lars Nessa explained in “The Summit,” “the main tactic is to minimize your time under the serac.”

As the trailbreaking group headed toward the Bottleneck, it became apparent that they’d begun fixing rope way too early on the course, which meant that not enough rope was left for the most difficult parts of the climb.

The group of 25 was brought to a standstill as climbers had to move back down the course to collect rope in order to move forward

In the afternoon, a climber from Serbia lost his footing and fell. Later, while attempting to move the body, a porter from Pakistan hired by the French team suffered from oxygen deprivation and fell to his death.

At around 4 p.m., the group was making its way across the Bottleneck when Dren Mandic, a climber from Serbia, lost his footing and fell.

Climbers watched as he tumbled down the side of the mountain and skidded to a stop. Mandic briefly stood up, and then collapsed again. Some of his Serbian teammates descended to attempt to help him, but it was too late. Mandic was dead.

While attempting to move Mandic’s body, the second death occurred. Jehan Baig, a high altitude porter from Pakistan who’d been hired by the French team, appeared to suffer from oxygen deprivation and began acting erratically. He slipped and plunged to his death.

After a brief discussion, the rest of the climbers decided to continue on toward the summit. They were descending in the dark when a ridge of ice fell on them and a Norwegian climber fell to his death.

The first set of climbers reached the summit at around 4:30 p.m. Hours passed as one by one they celebrated reaching K2’s peak. The last climbers to head off the mountain were Marco Confortola (from Italy) and Ger McDonnell (from Ireland) at around 7:30 p.m. Because of the late start, they would be descending back down to Camp 4 in the dark.

Around 8:30 p.m., a group of Norwegian climbers were passing through the Bottleneck on their way back down when a chunk of the serac fell on them, dislodging and cutting off the fixed lines that had been in place to help them descend, effectively stopping the group in their tracks.

As the heavy, sharp ice fell upon the group, Norwegian climber Rolf Bae lost his footing. His wife Cecilie Skog and their teammate Lars Flatø Nessa watched helplessly as Bae fell to his death.

Cecilie Skog had just watched her husband die. And now she had to save her own life by making her way down the mountain.

Skog and Nessa began moving down the mountain without fixed lines, relying on their pickaxes and crampons to make it back to Camp 4.

“Within high altitude mountaineering, there is an unwritten code that if someone is dying and you know you’re going to put your own life at risk, you should leave them,” explained Pat Falvey, a 2003 Everest summit leader, in the 2013 documentary about the K2 disaster, “The Summit.”

While some experienced climbers were able to free solo down in the dark, less experienced climbers who had made it up the mountain with the help of guides were stranded without the ropes.

A group of several Korean climbers became entangled in the dislodged ropes and were forced to wait for someone to come rescue them in the Death Zone.

While climbing up K2 is obviously dangerous, it’s actually descending from the summit that takes the most lives. One in four climbers who successfully summit K2 will not survive the descent.

That’s because extended time in the “Death Zone” can leave climbers in a state of extreme hypoxia. Deprived of oxygen, cells begin to die, and sufferers can experience extreme disorientation and confusion as the body shuts down.

As van de Gevel and D’Aubarede set out from the summit, D’Aubarede appeared sluggish and out of sorts. D’Aubarede signaled for van de Gevel to go ahead of him. And then suddenly van de Gevel looked back and D’Aubarede was gone. He, too, had slipped off the side of the mountain.

As the sun rose on August 2, the climbers who had made it back down to Camp 4 took stock of those still left on the descent.

Several Korean climbers and their Sherpas were still stranded above the Bottleneck in the Death Zone, waiting for rescue. The head of the Korean team ordered two additional Sherpas — cousins Tsering and Pasang Bhote — to bring them all down.

“They paid us and acted like they owned our lives,” Tsering Bhote said of the Korean team leader who made him and his cousin rescue his fellow Korean climbers.

Ger McDonnell and Marco Confortola attempted to help the entangled Korean climbers, working for hours to free them, unaware that several Sherpas were heading back up the Bottleneck path with the same goal.

After several hours, Confortola, concerned about his own oxygen deprivation, began heading back down the mountain. McDonnell stayed with the Koreans, and at one point, began climbing higher. Many of those who knew McDonnell believe he was attempting to strategize a way to free the Korean climbing group. McDonnell was never seen alive again. He is believed to have been killed by another ice fall.

Suddenly, an avalanche thundered down the side of the mountain and took a climber with it.

Confortola, now seriously struggling, spotted the body in the avalanche’s wake. He believed it to be that of Ger McDonnell.

“All of a sudden I saw an avalanche coming down. It was only 20 meters to my right,” Confortola said. “I saw the body of Gerard sweep past me.“

Other climbers disputed Confortola’s claim and believed that it was Hugues D’Aubarede’s high altitude porter Karim Meherban, whose body was never recovered.

Confortola continued to descend after McDonnell allegedly wandered back up, leaving the Korean climbers behind, but he didn’t make it all the way to Camp 4.

The Sherpas made it to the stranded Korean climbers, but another huge chunk of the ice ridge fell. More men died.

In the early afternoon, Tsering and Pasang reached the Korean contingent of climbers, who had weathered a cold night in the Death Zone with their cousin Jumic Bhote.

One of the Koreans was too severely injured to attempt the trek, and Tsering stayed behind with him. The two other Koreans, guided by Pasang and Jumic, made their way toward the Bottleneck.

But as they slowly descended, another huge chunk of the serac fell, raining ice and snow down upon the four-person group.

Tsering later recounted the horror of watching his brother and cousin fall to their deaths in the chaos.

Following their descents, several of the climbers had to be helicoptered to nearby hospitals for treatment.

Italian climber Marco Confortola and Dutch climber Wilco van Rooijen, were both treated for severe frostbite and lost toes.

Rooijen spent two full nights on the mountain by himself, experiencing hallucinations and snow-blindness.

“There were so many moments when I thought I saw a climber and thought I heard voices, but I knew there couldn’t be people there,” Rooijen said of the ordeal. “It was a scary moment when I knew I was reaching my limits. I was thinking no one knows where I am and they will not be coming back.”

Wilco Van Rooijen believes the K2 disaster was caused by a lack of communication and broken promises.

“The biggest mistake we made was that we tried to make agreements,” Rooijen told Reuters, speaking of the large numbers of climbers from different countries and teams attempting to share responsibility.

“Some people did not do what they promised,” he continued, singling out the Korean team for failing to bring the proper supplies to Camp 4.

In total, 11 people died over the course of 24 hours, on K2.

Kim Hyo, Park Kyeong, and Hwang Dong from Korea; Jimc Bhote and Pasang Bhote from Nepal; Jehan Baig and Karim Meherban from Pakistan; Hugues d’Aubarède from France; Ger McDonnell from Ireland; Dren Mandic from Serbia; and Rolf Bae from Norway.

Many questioned how they could leave so many of their fellow mountaineers on K2’s grueling slopes. But Lars Nessa believes most people simply don’t understand how difficult the climb really is.

Critics, Nessa says in “The Summit,” are “upset when people don’t go up and rescue people in this dreadful environment where you likely will be killed by doing so. There will be things we will never know, but the question you should ask is “What would you do?“

spacer

spacer

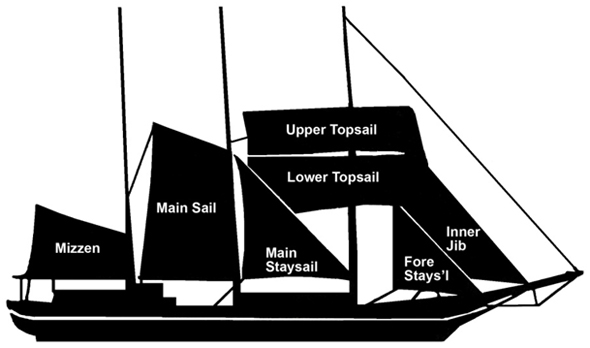

Abandon Ship: The Sinking of the SV Concordia

Storyline

Abandon Ship: The Sinking of the SV Concordia documents a near tragedy

Vancouver woman’s film tells the story behind the sinking of tall ship Concordia.

spacer

Students safe after capsizing of N.S.-based ship

Dozens of students travelling aboard a Nova Scotia-based ship that sank off the coast of Brazil Thursday are safe and suffered no serious injuries in the capsizing, officials from the school that organized the trip said Friday.

All 64 people aboard the tall ship SV Concordia, who were part of the West Island College Class Afloat program of Lunenburg, N.S., were rescued from four life-rafts by merchant vessels early Friday.

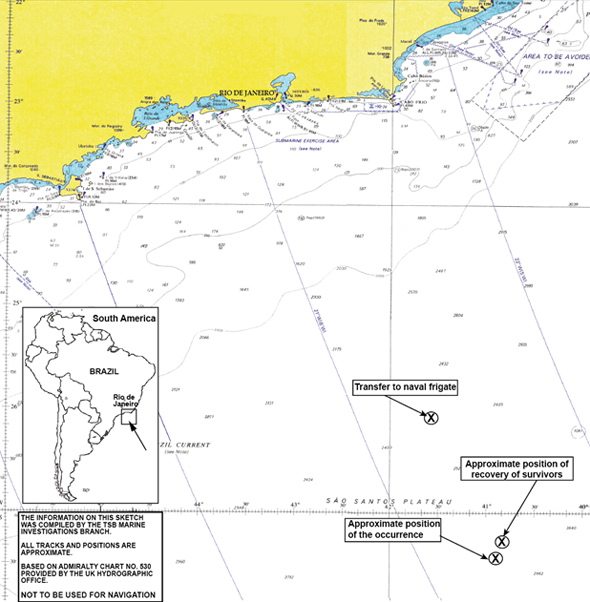

The Brazilian navy said their ship went down in rough seas about 550 kilometres southeast of Rio de Janeiro.

The 48 students, eight teachers and eight crew members had to abandon ship and spent the night in the life-rafts, which were equipped with blankets and some food. A Brazilian navy helicopter spotted the rafts and dropped medical supplies down to them.

The students, teachers and crew will spend Friday night on two merchant vessels. It’s expected they will be moved to a navy frigate and be taken to Rio de Janeiro Saturday morning.

Drake Hicks, one of the students on board the Concordia, spoke to the CBC Friday evening from the merchant ship Crystal Pioneer.

“We got on our emergency suits. There were a lot of people who were frantic and, you know, obviously very scared,” she said.

Hicks and the others spent 18 hours in the life-rafts before being pulled to safety.

“Big waves in a small, tiny raft is not fun,” Hicks said. “There were a lot of people who were throwing up a lot. It was definitely scary. We were all dehydrated, blurred vision, and then they harnessed us in and pulled us up.”

Evacuation probably ‘very difficult’

Kate Knight, head of the school, said school officials know everyone is all right, but have heard little else.

“We just don’t have any information about the state of the vessel or what caused the need to abandon ship,” she told reporters in Lunenburg.

“We’re taking it hour by hour while we update families.”

The drama on the high seas began Thursday around 8 a.m. AT, when Brazilian search authorities received a distress signal from the 57-metre ship. They contacted the rescue co-ordination centre in Halifax, which alerted the school.

Terry Davies, spokesman for Class Afloat, a program that allows high school students to study while at sea, said his group tried in vain to contact the ship by email and satellite phone.

“We were finally able to confirm last night [Thursday] at 8 o’clock that the Brazilian authorities were sending their folks to the last reported co-ordinates,” he told CBC News.

Davies said the fact that everyone managed to get off the ship safely is testament to the crew’s expertise.

“Well, it does speak to the quality of the training,” he said. “A superb execution of an evacuation that probably was very difficult. To come out of something that involves potentially the loss of a vessel and come away with all of its crew is probably nothing short of remarkable.”

Brazil’s navy said it picked up the distress signal from Concordia and alerted merchant vessels. Three hours later, a military plane spotted a life-raft in the area from which the signal came.

Rear Admiral Leonardo Puntel of the Brazilian navy told CBC News that the plane was able to tell the merchant ships where to look for survivors. By the time a navy rescue ship arrived, all Concordia passengers and crew had been plucked to safety by the Hokuetsu Delight and the Crystal Pioneer.

“There were two injuries, but they were minor,” said Puntel.

The navy said it was told by the Concordia crew that their ship capsized in high seas.

Anxious parents

It has been a terrifying time for parents of the students.

Shelley Piller, whose daughter Alicia was aboard the Concordia, said she heard from school officials late Thursday night that the ship had sunk and everyone spent 18 hours in life-rafts.

“We were just absolutely horrified, and we’ve been up all night,” Piller told CBC News from her home in the community of Kenilworth, about 50 kilometres northwest of Guelph, in southwestern Ontario.

Brad Unsworth’s 16-year-old daughter, Lauren, was on the Concordia.

Unsworth, of Amsterdam but originally from Halifax, said that he couldn’t eat or do much of anything when he heard the ship was in trouble.

“It was really up in the air what the status was on the children — whether there were any survivors; if so, how many,” Unsworth said. “When they came back and confirmed the students and crew were OK, of course, that was a huge relief.”

Five of the students are from a Calgary-based private school, which is also called West Island College.

“It is a great relief to know our students are safe and will soon be reunited with their families,” CEO Carol Grant-Watt said in a statement.

“I want to thank parents and students for their understanding and support. This morning, we held a student assembly and are continuing to help our students and faculty deal with this news.”

Knight said school officials were on their way to Rio to meet with the students and crew.

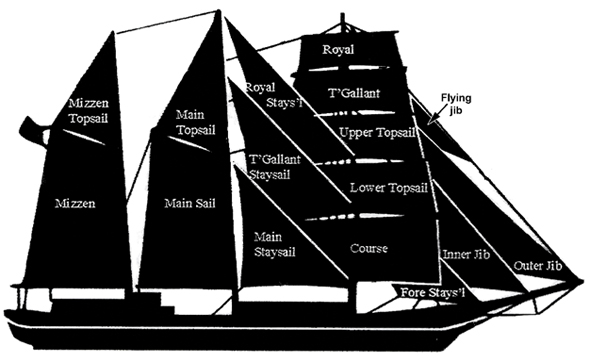

The tall ship left Lunenburg last September carrying students in Grades 11 and 12 and first-year university. Most are Canadian, with others coming from the U.S., Mexico, Japan and other countries. The floating school had been expected in Montevideo, Uruguay, on Thursday.

Safe ship

The Concordia was built in 1992 in Poland. It meets “all of the international requirements for safety” and passed inspections by the U.S. and Canadian coast guards, the school’s website states.

“We have a very good safety record, and, certainly, we have never had an incident or anything remotely related to this,” said Knight.

Knight said the life-rafts are all equipped with blankets, medical supplies, food and water.

Students are required to take part in abandon-ship drills regularly, Davies added.

People who know the Concordia said it’s difficult to imagine what could have caused it to sink.

Kevin Feindel, business manager at Lunenburg Industrial Foundry & Engineering Ltd., said the Concordia is a large, well-built ship with a very experienced crew.

“It’s hard to imagine a set of circumstances that would make her capsize or take on enough water to make her founder,” he said.

Michele Stevens, who makes sails at her shop just outside Lunenburg, outfitted the Concordia and has also sailed on the vessel.

She said the Concordia was a good ship.

“I felt that the boat was very stable, and I felt the sides seemed quite high enough,” she said. “I felt very secure on the ship at all times. They didn’t take any risks at all, I felt.“

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada will assist its counterparts in Barbados, where the Concordia is registered, in investigating the cause of the sinking.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper thanked the Brazilian navy and the merchant ships for their “swift and heroic response.”

“The skill and compassion demonstrated by Brazilian rescuers is a tribute to their training, spirit and seamanship,” Harper said in a statement. “Their efforts are deeply appreciated by Canada and will undoubtedly serve as an inspiration to the young Canadians who were aboard the SV Concordia.”

Canadian Foreign Minister Lawrence Cannon also issued a thank you to Brazilian authorities.

With files from The Associated Press

Crew error cited in Concordia sinking

A new report about the SV Concordia sheds light on why the Canadian tall ship, carrying students and staff, capsized last year, CBC’s Tom Murphy reports

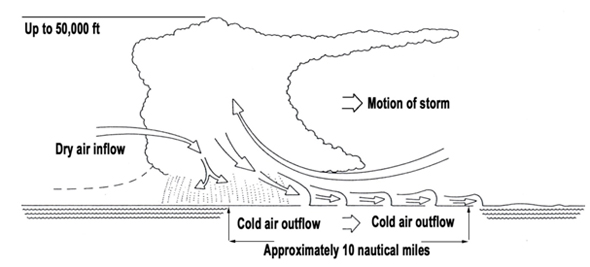

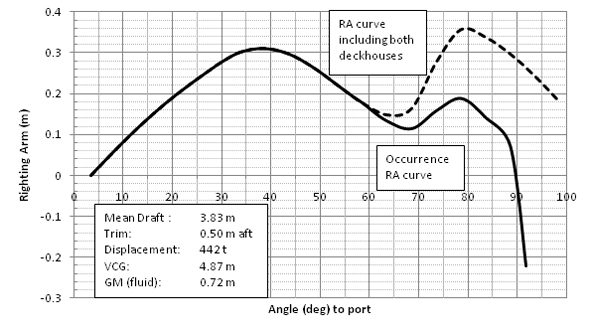

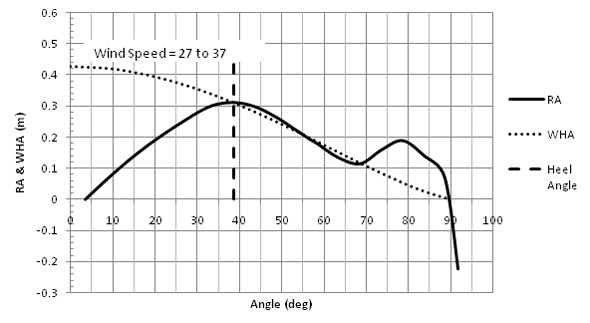

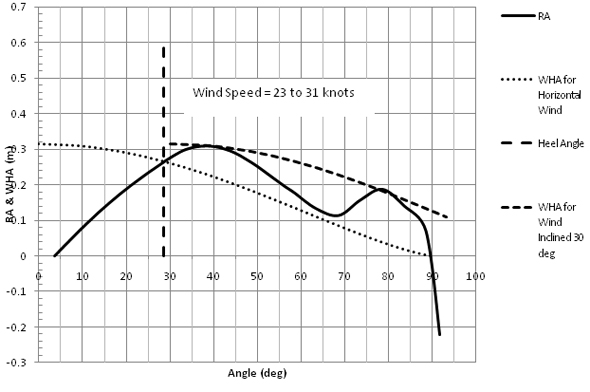

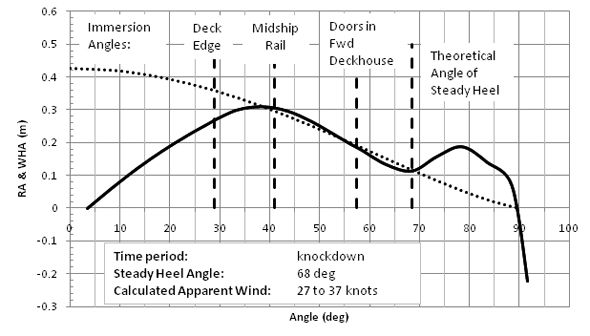

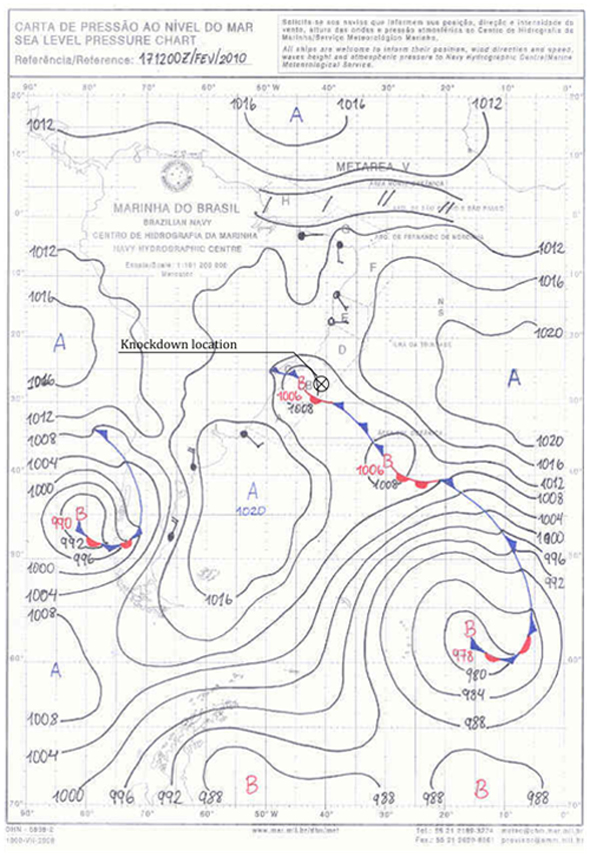

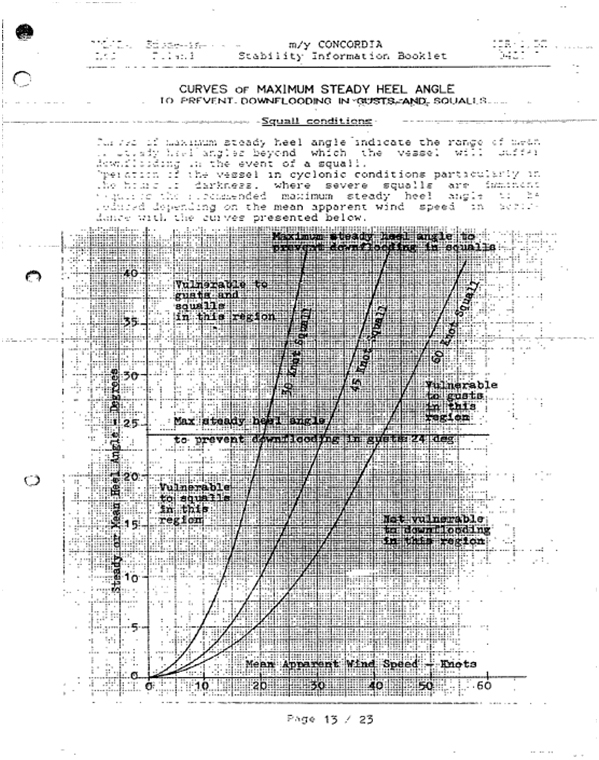

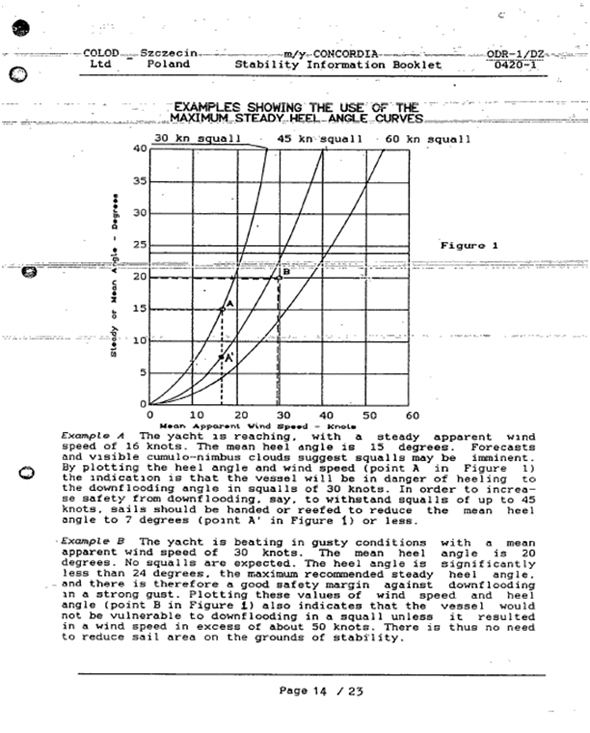

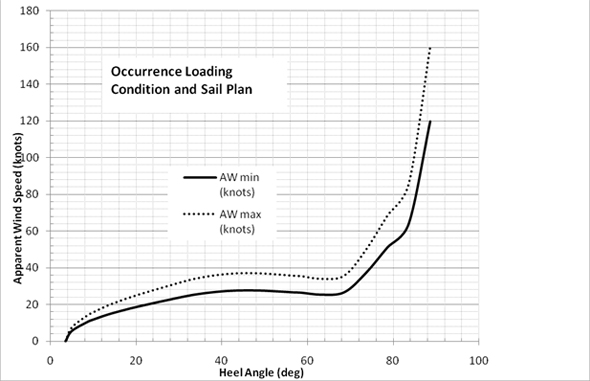

A tall ship carrying 64 students and staff was lost in a squall off Brazil because the crew didn’t understand the risk of a knockdown, transportation safety officials say.

The Transportation Safety Board released a report Thursday into last year’s capsizing of SV Concordia, a Nova Scotia-based floating school.

The ship sank on Feb. 17, 2010, about 550 kilometres southeast of Rio de Janiero. All those on board, including 42 high school and university students from Canada, were rescued. No one was seriously hurt.

The TSB found that the master didn’t tell the second officer how to react to changing weather conditions and maintain the stability of the ship.

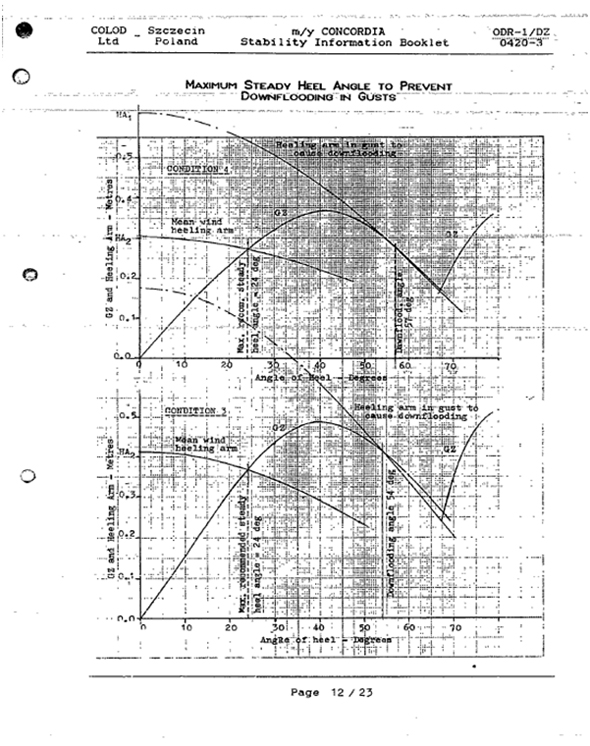

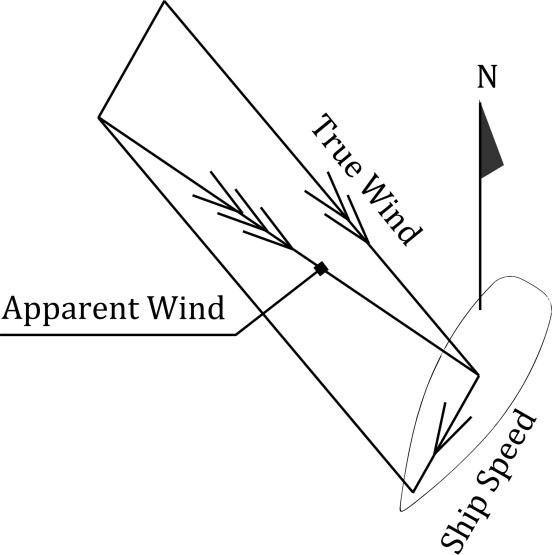

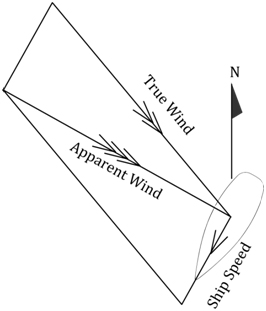

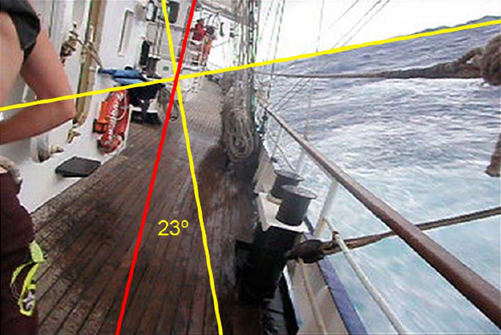

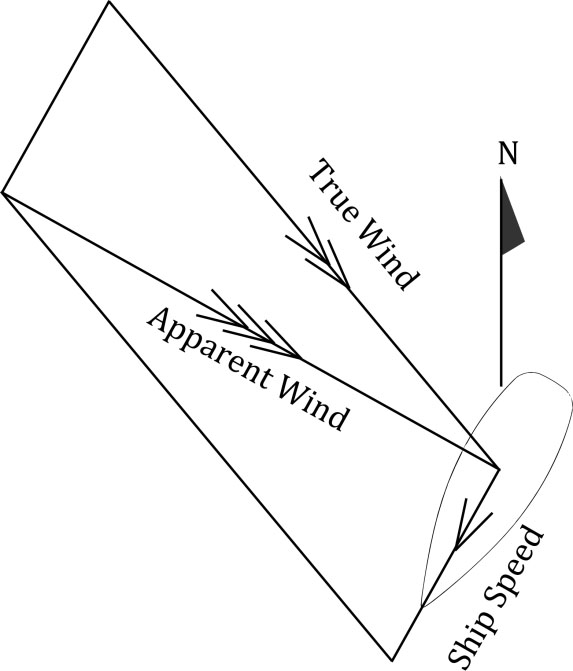

When the weather worsened, the second officer didn’t perceive a threat. The ship began to heel beyond 23 degrees, but at that point it was too late to steer downwind or change sails.

“The officer of the watch observed the wind speed increasing and shifting forward, the vessel started heeling further,” said senior marine investigator Paulo Ekkebus. “Although he tried to remedy the situation by altering course, the vessel was knocked down.”

Doors and windows were left open. When enough water flooded inside, the ship capsized.

“Concordia’s shore-based management did not provide direction on the need for squall tactics and stability booklet familiarization, which would have provided an additional defence against a knockdown and capsize,” the report states.

The board found that there was no evidence of a microburst — a sudden downdraft of air in a small area — as first believed.

“Satellite imagery, expert assessment and onboard observations suggest that the wind speeds were not extreme,” board member Jonathan Seymour said Thursday at a press conference.

“Certainly the conditions were no worse than this vessel must have encountered many times before.”

The capsizing of the ship was followed by a harrowing 41-hour wait for rescue. The students and staff were adrift in life-rafts until merchant ships plucked them from the Atlantic Ocean.

There were problems with the bailers, foot pumps and flashlights, and a lack of stowage for emergency equipment, the board found.

The board recommended that watchkeepers aboard sail training ships have stability guidance training, especially in bad weather, and that international standards be improved to require officers of such vessels be trained to mitigate the risks.

There are currently seven Canadian-flagged sail training vessels. Every year they carry more than 2,500 sail trainees.

our beloved SV Concordia sinks !!!

I was absolutely stunned when I logged onto the Canadian Broadcasting Corp news site this morning and saw that the tall ship SV Concordia had gone down in a big storm. For those of you who don’t know the Concordia, it is a 200ft tall ship that sails around the world with 45 grade 11 and 12 students aboard – mostly from Canada. Yvonne and I taught/sailed on the ship for 11 months in 1999/2000. In March 2000 (almost 10 yrs to the month) we sailed across the Atlantic (from Namibia, ironically) to Brazil. That is where the ship sunk today – 500km off the coast – a place we had sailed very close to. This was our home for almost a year, and represents probably the most remarkable year I have ever lived.

I am SO relieved but honestly surprised that everyone made it out alive. We did regularly practice abandon ship drills, but it was always calm. If the ship had capsized, all hell would have broken loose, and it is remarkable that they managed to all make it into the life rafts. I recall vividly the placement of these rafts, and always wondered what would happen if push came to shove.

We know very well the man who is quoted in the news – Terry Davies created the Class Afloat program and was the one who hired us. He was Yvonne’s principal at West Island College. He had to live hours of his life not knowing what happened to the students, teachers and crew and had to tell parents that the ship had gone down. This ship program represents his life’s work. He no doubt aged 10 yrs last night.

We also feel so badly for the students and teachers who have had their remarkable voyage cut short. They will likely now finish their academic year in Lunenburg at the school’s land base. It is a rigorous academic program, so completion will be paramount or students loose an entire year. Some of the students just joined the ship in January . We feel terribly for the professional crew (most from Poland) who now are without work. They did a remarkable job keeping everyone alive, I believe.

We’ve attached a few photos from our time aboard the ship. Every 5 yrs the ship circumnavigates the globe, and we were lucky to be on that year. I took the photos of the ship from one of the small tender craft as we sailed to the Solomon Islands in the Pacific.

Since seeing the news we have since heard from a number of you – thanks for your thoughts. This program changed the lives of hundreds (thousands?) of students and teachers – including ourselves. It is a very sad day.

Cam

|

|

spacer

Why didn’t Concordia right herself? And why was there a 26-hour delay in mounting a rescue?

The sinking of the tall ship Concordia off Brazil has raised questions about the 26-1/2-hour delay in launching a rescue as well as the vessel’s stability. But the evacuation of the 188-foot three-master without loss of life was unquestionably a feat of crew discipline and training that prevented misfortune from escalating into tragedy.

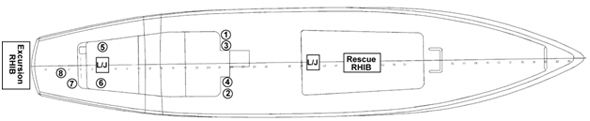

The 64 students and crew aboard the Canadian school ship survived the Feb. 17 sinking 344 miles out. Concordia’s captain, William Curry, says he thinks a microburst – a violent downdraft that struck suddenly and without warning – knocked the ship on its side. Unable to recover, Concordia sank in less than half an hour, but before it did the crew shepherded all of the students – high school juniors and seniors and college freshmen – on deck and into four 20-person rafts.

“The best analogy I can think of for this is the landing of that airliner in the Hudson River,” says Bert Rogers, executive director of the American Sail Training Association in Newport, R.I., an organization for school ships. “The professional judgment and skill of the captain and the training and readiness of the crew and the students allowed the evacuation to come off without loss of life.”

Why did that take so long, especially with a large school ship involved? “This has been the question of the day,” says Nigel McCarthy, president and CEO of West Island College International in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, which operates the Class Afloat school aboard the 18-year-old barkentine.

Concordia was sailing from Recife, Brazil, to Montevideo, Uruguay, when stormy weather threatened the afternoon of Feb. 17. Curry, in an interview with Canada’s CBC Radio, says the crew had shortened sail 24 hours earlier in anticipation of deteriorating conditions, but the wind had not piped up yet.

Curry says it was blowing just 16 to 17 knots. He was below in his cabin when Concordia suddenly heeled. He expected the ship to stiffen up and accelerate and sail through the gust, but she didn’t. Instead, she hesitated and then went over on her side, masts in the water in a 100-degree knockdown. It all happened in maybe 15 seconds.

Curry says it appeared Concordia was knocked down by a microburst, a violent, localized downdraft that often comes literally “out of the blue,” hits the water vertically and accelerates horizontally as it disperses along the surface.

“He said, ‘It knocked us down, and we couldn’t come back up,’ ” McCarthy says.

Fortunately, many of the students were studying in classrooms on deck, where they were able to don life jackets or immersion suits, leap into the water or make their way to the masts to shimmy down to the life rafts. Others had to scramble up from below, where ports were breaking and water was flooding in.

The rafts were rugged New Zealand-manufactured RFDs – with canopies – that had been stored in canisters on the side of the deck that was still above the surface. (The canisters on the other side of the deck were under water.) Curry says a pontoon or inflation tube on one of the rafts deflated on the second evening, but the occupants stayed in it until their rescue the next morning.

The rescue

The students and crew had just come off three days of safety drills, including abandon-ship tactics. “The fact that their evacuation plan did not unravel is a testament to their training, planning, judgment and drilling,” says ASTA’s Rogers.

Concordia was carrying a half-dozen radios and a satellite phone, but they all were in the radio room, which was under water within seconds of the knockdown, Curry told CBC radio. The inability to transmit a mayday or respond to calls from the Brazilians as they tried to confirm that the school ship was in distress factored into the reluctance to launch a rescue operation immediately.

A geostationary satellite received the distress signal from Concordia’s EPIRB at 2:04 p.m. Feb. 17, but the ship’s GPS location was not embedded in the signal (not all beacons have integral GPS), says Lt. Shawn Maddock, operations support officer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s SARSAT office, which monitors satellite search-and-rescue operations around the world. Exactly 20 minutes later, a low-earth orbiting satellite picked up the signal, and by 2:29 p.m. it had calculated a position for the EPIRB using Doppler shift. That information was sent on to the Mission Control Center in Brazil.

Brazil’s First Naval District in Rio de Janeiro, which coordinated the rescue operation, told reporters it wasn’t notified of the distress alert until 9 p.m. The district’s public affairs officer did not respond to two e-mails asking what happened overnight, but Maj. Denis McGuire, officer in charge of the Joint Rescue Coordination Center in Halifax, Nova Scotia, says his office received a call from the Brazil navy at 7:15 the next morning, Feb. 18. “They advised us they had an EPIRB alert,” he says.

Concordia is registered in Barbados, so the Brazilians would have traced the EPIRB’s owner through the International Beacon Registration Database instead of Canada’s national EPIRB registry. McGuire says the Brazilians had the name of the vessel and the operator – West Island College International in Lunenburg – and asked JRCC in Halifax to contact the school. McGuire suspected there might be a language problem. He says his office reached school authorities about 8:30 a.m. McCarthy says the school then tried to contact the ship by satellite phone and e-mail and “got absolutely no response.”

It wasn’t until 5 o’clock that afternoon that the Brazilians dispatched an air force plane to find the EPIRB. (They already had its location.) The plane spotted three of the rafts three hours later. The navy then diverted two merchant vessels, the Philippine-flagged Hokuetsu Delight and Cayman Islands-flagged Crystal Pioneer, which reached the survivors after midnight.

Rescue operations didn’t commence until shortly after dawn. “It’s the ship’s master’s call when to do the rescue,” says Benjamin Strong, spokesman for Amver, the organization that recruits merchant ships to assist in rescues at sea.

The ships were positioned so the rafts were in their lee, and crews lowered embarkation ladders so survivors could board from the rafts, says Strong.

Investigations

The Barbados Maritime Ship Registry, headquartered in London, is investigating the sinking. “Our interest is focused on witness statements providing us with an insight into the situation on board prior to the event, the situation on board during the event, and lastly the circumstances surrounding the successful rescuing of all persons on board,” says C.D. Sawyer, the registry’s principal registrar, in an e-mail.

On March 3, the Transportation Safety Board of Canada decided to open its own investigation, focusing on factors contributing to the sinking. Some expert observers are hoping that investigation will look closely at the ship’s stability. Built in 1992 in Szczecin, Poland, at the Colod Co. Ltd. yard, the steel-hulled Concordia was designed to the Lloyds Registry 100 A1 yacht classification, built under Lloyds supervision and inspected annually by Lloyds, McCarthy says.

“There is really no international agreement on a stability standard for sailing ships,” says naval architect Roger Long of Cape Elizabeth, Maine. Long has designed a number of oceangoing research vessels, including the Sea Education Association’s sailing ship, Corwith Cramer. He was the principal researcher and co-author of papers used to develop Coast Guard stability regulations for school vessels in the 1980s and was an expert witness for the British government in the inquiry into the 1984 capsize of the school ship Marques in a gale during a tall-ship race from Bermuda to Halifax. Nineteen of 28 crew died in that tragedy.

The Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail reported March 2 that Classes Afloat founder and chairman Terry Davies says the ship underwent a stability test during construction that showed she could recover from a 110-degree knockdown.

Long acknowledges that there are “events” at sea that almost no ship can survive. But from what he has read so far of the captain’s accounts of the incident, Long says it didn’t appear as if the violent wind that knocked Concordia down was sustained – in other words, it didn’t pin the ship down. “I would have expected [Concordia] to have come back up again,” he says.

Students enrolled in Class Afloat’s 2010 spring semester-at-sea were scheduled to sail for five months and visit Recife, Montevideo, Tristan da Cunha, Cape Town (South Africa), Walvis Bay (Namibia), St. Helena, Georgetown (Ascension Island), Fernando de Noronha (Brazil), Port of Spain (Trinidad), Hamilton (Bermuda), and back to Lunenburg. Cost for a semester-at-sea is $27,700.

This article originally appeared in the May 2010 issue.

spacer

Marine Investigation Report M10F0003

Knockdown and capsizing

Sail training yacht Concordia

300 miles SSE off Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content.

Summary

On 17 February 2010, at approximately 1423, the sail training yacht Concordia was knocked down and capsized after encountering a squall off the coast of Brazil. All 64 crew, faculty, and students abandoned the vessel into liferafts. They were rescued 2 days later by 2 merchant vessels and taken to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Le présent rapport est également disponible en français..

1.0 Factual Information

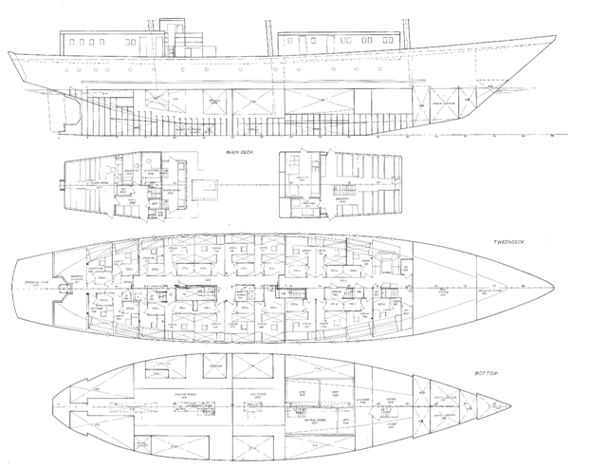

1.1 Particulars of the Vessel