Inquiring minds, where are you? Don’t you even wonder why it is suddenly SO IMPORTANT to retrieve all the old Temples and Mark them for Protection; meaning they are now owned and controlled by the NWO? Why the rebuilt/restored the Colosseum? Why they are planning to erect the ARCHWAY/GATEWAY to the Temple of BAAL all over the world? Now, they are working to rejuvenate the Idols by bringing color/life back to their cheeks.

They are doing all these things for the same reason that they have been collecting the DNA of all the dead Rulers, Monarchs, heroes and Giants of the ancient past. They have also collected the DNA of all the monstrous creatures and human/hybrids.

Why?? Because the are restoring the PAGAN world! They want humanity to be subject once again to the control fo the Pagan Gods and living in fear of the Monsters and Giants that serve them.

spacer

Coloring the Past: An interview with Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann

Designer Creates Lifelike Images of Roman Emperors with Machine Learning

Daniel Voshart used his expertise to bring 54 Roman emperors back to life.

It’s not every day that you face a Roman emperor, but now you can. Sort of.

Designer, Daniel Voshart, has created photorealistic images of 54 Roman emperors thanks to machine learning tools, and his artistic eye. Voshart based the faces on traditional stone bust images.

Now that’s a way to pass time during the lockdown, which, as it stands, is exactly why Voshart took on the fun project, as he stated in his blog.

SEE ALSO: MIT ALGORITHM DISCOVERS SUBTLE LINKS BETWEEN GREAT WORKS OF ART WITH AI

Bringing art to life

Cinematographer and virtual reality designer, Voshart, made use of machine learning, Photoshop, a neural network, his artistic flair, and research to create these stunning life-like images.

Voshart used the neural network, Artbreeder, which then analyzed roughly 800 busts to create realistic face shapes, features, hair, and skin, and then added color, per Live Science’s report.

As he told the Verge, “I would do work in Photoshop, load it into ArtBreeder, tweak it, bring it back into Photoshop, then rework it. That resulted in the best photorealistic quality, and avoided falling down the path into the uncanny valley.”

Different emperors have different skin tones in Voshart’s images, which he explained can be altered and are based on “educated guesses based on birthplace and U.V. sun exposure maps,” per an email from Voshart to us.

https://twitter.com/dvoshart/status/1296664866166575109/photo/1

Tracking down all the art and texts for his project took Voshart around two months, and each portrait took him approximately 15 to 16 hours to create, he told Live Science.

The images are an incredible representation of what a human mind and AI can create together. Take a look at all 54 ancient emperors and what they may have really looked like:

Many art historians preferred to imagine, incorrectly, that all ancient marble was gleaming white

Alma-Tadema was making a bold statement with this painting: the colour had been lost from the sculptures by the time they were shown in the British Museum. More than two millennia of weather and war had bleached the marble white. And from the 18th Century onwards, many influential art historians preferred things that way: men like Johann Joachim Winckelmann – whose two-volume history of ancient art was published in 1764 – liked to think of ancient sculpture as a mass of beautiful, gleaming white.

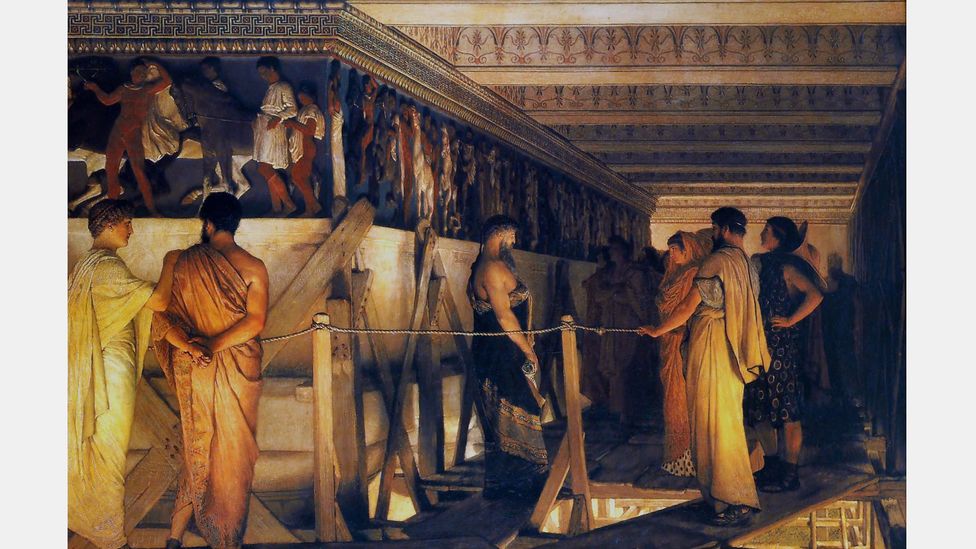

Lawrence Alma-Tadema painted Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends, which depicted the Athenian structure as brightly painted (Credit: Alamy)

Winckelmann was a particular fan of Roman marble copies of Greek bronze statues: the Romans often copied Greek originals in marble. You can tell it is a marble copy of a bronze if a figure is leaning on something: a tree trunk, or a staff, for example. Or perhaps there is a little chunk of marble joining the two legs together. Marble lacks the tensile strength of bronze, so it requires extra support to keep the figures stable.

So when Alma-Tadema painted the Parthenon Frieze and included his imagined version of the lost colour, he was picking a side in an art history battle which still rages today. There are plenty of people now who find the notion of painted marble or bronze an affront to their impression of the past as an austere, unadorned place.

Phidias also sculpted a large statue of Athena to stand at the Parthenon – it was covered in gold and ivory (Credit: Getty Images)

Yet ancient art would have been a riot of colour and glitzy decoration. Phidias – the most celebrated sculptor of his day – also created a huge statue of Athena Parthenos to stand inside the Parthenon (it takes its name from the description of the goddess: parthenos means ‘maiden’). Although the statue is long since destroyed, we have a description of it in the writings of the ancient historian, Pausanias. He tells us the statue was chryselephantine: covered in gold and ivory. There is a modern-day replica of the statue in Nashville, by the sculptor Alan LeQuire, which surely captures something of the glittering original.

|

| Roger Michel, IDA (Institute of Digital Archeology) Founder and Executive Director said: “As the preeminent global symbol of international cooperation indeed, itself an iconic monument to peace, the United Nations is the perfect place to unveil our latest collaboration with the Dubai Future Foundation, a reconstruction of Palmyra’s famous Statue of Athena. For thousands of years, Athena was synonymous with reason, refuge and the rule of law all of the same values on which that historic institution was built. (posted in 2017) |

Dulled by time

Even bronze statues would have been much brighter than their dark brown appearance suggests today: bronze acquires a patina over time. What we see as a uniform greenish-brown head would once have been gleaming bright, almost golden. Hair would have been painted dark and the flesh might well have been painted too. The eye sockets of ancient statues are often empty, because the eyes were made separately, and they have been lost over time. There is a magnificent pair of Greek eyes in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, made of bronze, marble, quartz and obsidian. The bronze eyelashes are particularly delightful, if a little disconcerting.

Ultraviolet light can be used to detect traces of colour on otherwise bare statues

Archaeologists have been able to use ultra-violet light to read colour on statues which retain no obviously visible signs of their decoration. Although it is not always possible to identify the precise colours used, the patterns which were painted onto the surface of a statue are often easier to spot. The statues from the Temple of Aphaia on the Greek island of Aigina are a perfect illustration of this. The statues from the western pediment of the temple are now housed in the Glyptothek in Munich, where German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann has examined them under UV light. The pediment had Athena at its centre, her plumed helmet tucking in beneath the highest point of the roof. In UV light, we can finally see the repeating, geometric decoration of her snaking shawl and the front of her robe.

The eyes of bronze statues in ancient Greece were usually made separately – and frequently are missing from the statues that still survive (Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

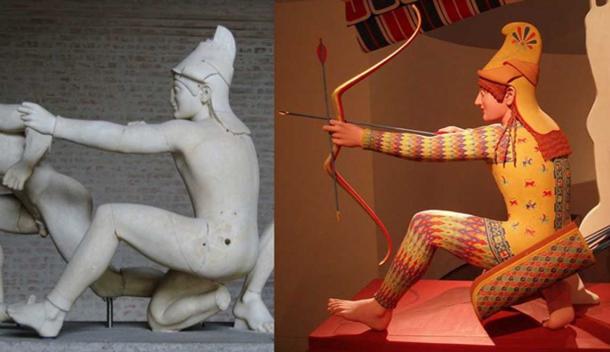

Trojan archer (so called “Paris”), figure W-XI of the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia, ca. 505–500 BC Polychrome reconstruction from the exhibition Bunte Götter. ( CC BY-SA 2.5 )

Further along, bending into the lower part of the slanted roof, was the figure of an archer (perhaps Paris, son of Priam of Troy). On his arms and legs, we can see traces of a diamond pattern. Brinkmann has spent years recreating the brightly-coloured decoration on copies of the statues which the Ancient Greeks would have seen all around them. This archer is one of his most spectacular: an intricate design of blue, red, yellow and green diamonds interlock, to give the archer ornate leggings and sleeves. His quiver is decorated in a similar colour-palate, with a slightly different design, almost like scales. The bow is painted red and gold, and even the arrows are decorated red. The archer is one of the stand-out pieces in Brinkmann’s Gods in Colour exhibition, which has toured the world for the past 15 years.

Left: ‘Peplos Kore’, circa 530 BC ( CC BY-SA 2.5 ) Right: Reconstructed in polychrome as Athena by Brinkmann team ( CC BY-SA 2.5 )

In living colour

And Brinkmann is not alone in his attempts to reintroduce colour to ancient sculpture. The Museum of Classical Archaeology in Cambridge has also tried to bring some colour into its plaster reproductions of ancient statues. The original (now white) Peplos Kore – a statue of a young girl, wearing a long dress belted at the waist – stands in the Acropolis Museum in Athens. The dress of the Cambridge copy is painted bright red, with blue borders, and blue, green and white decorations. She has also acquired a pair of feet, lost from the original marble version, and a new left arm. The Acropolis Museum itself makes a bright option available too: they encourage visitors to their website to decorate their own versions of the peplos (dress), allow you to investigate archaic colours and see which colours were available to painters in the ancient world.

Paint would be applied directly to bronze or marble, as depicted in this recreation of the Prima Porta statue of Augustus (Credit: Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford)

And the Greeks are not the only ones whose statues were painted: the Romans were similarly enthusiastic about brightening up their marble. Paolo Liverani, of the University of Florence, has worked on a project to recreate the statue of Augustus of Prima Porta. The emperor’s statue was discovered in 1863, and showed traces of the paint which once decorated it. A cast of the statue, its polychromy restored (and, in part, imagined), now stands in the Vatican Museum. (Why is a so called Christian organization lifting up statues of Pagan Idols?) The decoration has changed hugely since Greek times: the statue of Augustus dates from around 20 BCE. Augustus’s breastplate is decorated not with a geometric design, but with figures. His cloak is a deep red, the edges of his tunic are vivid red and blue.

Statues could be outfitted with shields and helmets – newly cast bronze gleams like gold, as opposed to the dull hue most of us see (Credit: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco)

And further south in Italy, we have one of the best-preserved sites from the ancient world. Herculaneum, near Pompeii in the Bay of Naples, was buried in ash when Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE. Its relics have been preserved differently from those in Pompeii, because the two sites are different distances from the volcano. Pompeii was hit with larger chunks of rock, for example, which destroyed the top floors of its buildings. Herculaneum still has carbonised wood in place, which was burned away in Pompeii.

In 2009, a team of scientists in Southampton began the digital recreation of a painted statue of a wounded Amazon warrior which had been found at Herculaneum. The front of the Amazon’s face had been destroyed, but her red hair, curling out from a centre parting (as Roman girls would have worn their own hair) was clearly visible.

The global audience for Brinkmann’s Gods in Colour exhibition has surely proved that there is an appetite for modern recreations of the brightness of ancient statuary. Aside from anything else, it reminds us how distant the Romans and the Greeks were from us, even though they often feel so familiar. The white marble statues or columns we have built in homage to the ancients say more about us – and the way we choose to imagine the ancient world – than they do about the people who lived 2,000 years ago or more. And perhaps the debate which had divided the art world for 100 years by the time Alma-Tadema was painting his version of the Parthenon can finally be set aside. Accustomed as we are to seeing the statues of ancient Greece and Rome in gleaming white, we understand them better if we remember their original colours.

Some statues were ornamented with garments, such as this cuirasse (Credit: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco)

spacer

A More Colorful Ancient Greece: Pigment Proves Classical Statues Were Once Painted

Once upon a time, long before wars, natural disasters and erosion took hold of the ancient Greek statues, these ivory gems vibrated with color. Ancient Greek sculptors valued animated and pulsating depictions as much as they valued perfection and realism, and it has finally become fact that these artists utilized color in their creations. The stark white Parthenon once breathed in blues, yellows and reds, and—though it took thousands of years for this to be solidified in art historical circles—now, scholars are finally able to display the ancient world with the same rainbow vitality it once possessed. (Vitality is another word for LIFE)

A Laughable Concept

The 19 th century saw the first inklings of possible painted sculpture, but it was not until the innovation of ultraviolet light and special cameras in the late 20 th century that finally provided unequivocal evidence of the painted marble. In fact, the mere idea that the sculptures were painted at all was considered laughable until the late nineteen-hundreds, when archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that the statues were once richly painted. Even then, Brinkmann’s earliest representations of what colored statuary might look like were deemed “gaudy”, due to the overwhelming rich color schemes he depicted. Yet, with time and perseverance, Brinkmann eventually proved all his naysayers wrong.

Trojan archer (so called “Paris”), figure W-XI of the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia, ca. 505–500 BC Polychrome reconstruction from the exhibition Bunte Götter. ( CC BY-SA 2.5 )

While the ancient bronze statues were likely not painted due to the extensive incorporation of inlaid jewels, gems and other metals in their forms, the marble statues of both ancient Greece and Rome have shown traces of pigment since their various rediscoveries in the Renaissance. However, unbeknownst to those fifteenth and sixteenth century pre-archaeologists, those faint traces of color were indicative of a once elaborately decorated sculpture—not just of residue from these pieces being long misplaced. It is because of this lack of knowledge that Renaissance sculptors intent on copying Greek and Roman forms carved their statues in unpainted, white marble; as far as they knew, unpainted white marble was precisely the way their ancient forebearers had sculpted.

Perishable Pigment

Now that it is understood and widely accepted that the trace pigments found on these statues are remnants of marble once colored, there has been further research into the nature of the paints and dyes used (and thus the reasons behind why and when those colors likely faded or were removed). In ancient Greece, pigments were created through a mixture of minerals “with organic binding media that disintegrated over time”. Thus, the paint held fast to the marble for many years but was slowly chipped away due to intense natural erosion and harsh weather, various stages of cleaning and—of course—the impact of warfare. What remained by the time of the Renaissance into the nineteenth century were the stark white statues that survive today.

Right: Original Trojan archer (so called “Paris”), figure W-XI of the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia, ca. 505–500 BC.( Public Domain ). Right: Polychrome reconstitution from the exhibition Bunte Götter.( CC BY-SA 2.5 )

Colorful Discourse

The debate regarding color on Greek statuary was long and arduous for scholars before and during Johann Winckelmann’s time. It had long been postulated that Greek statues were likely covered in paint; however the comical, clown-like reproductions produced made most researchers scoff and laugh. Thanks to Winckelmann, it is now certain that color was as important in ancient sculpture as any other aspects. The Greeks not only wanted to worship their gods and goddesses in gloriously perfect human forms; they wanted their gods to resonate with all the “colors of the wind”. (Isn’t that in a Disney Song? Disney, King of spell casting and manipulation.)

Coors of the Wind – Live Orchestra/ Pocahontas Masterpiece

Pocahontas | Colors of the Wind | Disney Sing-Along – YouTube |

|

You think I’m an ignorant savageAnd you’ve been so many placesI guess it must be soBut still, I cannot seeIf the savage one is meHow can there be so much that you don’t know?You don’t know

You think you own whatever land you land onThe Earth is just a dead thing you can claimBut I know every rock and tree and creatureHas a life, has a spirit, has a name

You think the only people who are peopleAre the people who look and think like youBut if you walk the footsteps of a strangerYou’ll learn things you never knew, you never knew

Have you ever heard the wolf cry to the blue corn moon?Or asked the grinning bobcat why he grinned?Can you sing with all the voices of the mountain?Can you paint with all the colors of the wind?Can you paint with all the colors of the wind?

Come run the hidden pine trails of the forestCome taste the sun sweet berries of the EarthCome roll in all the riches all around youAnd for once, never wonder what they’re worth

The rainstorm and the river are my brothersThe heron and the otter are my friendsAnd we are all connected to each otherIn a circle, in a hoop that never ends

How high does the sycamore grow?If you cut it down, then you’ll never know

And you’ll never hear the wolf cry to the blue corn moonFor whether we are white or copper skinnedWe need to sing with all the voices of the mountainWe need to paint with all the colors of the wind

You can own the Earth and stillAll you’ll own is Earth untilYou can paint with all the colors of the wind

|

Top image: This statue was originally painted. Left: Painted replica of Augustus of Prima Porta statue with pigments reconstructed for the Tarraco Viva 2014 Festival ( CC BY-SA 3.0 ). Right: Original Statue in White Marble, 1 st century AD. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

By Ryan Stone

spacer

‘Gods in Color’: Shining new light on ancient statues

The knowledge that ancient Greek and Roman statues were colorfully painted has largely been suppressed in recent centuries. An exhibition explores this shaded past and shows figures in their vibrant original hues.

We often think of ancient statues as the white stone figures that have long dominated museum collections. But in recent years, the public has been reawakened to the fact that many of these antiquities were once brightly colored.

In the exhibition “Gods in Color – Golden Edition,” which features over 100 painted sculptures in Frankfurt’s Liebieghaus museum, visitors can witness the polychromatic transformation of ancient statues and experience their original, eye-opening bright hues.

The myth of colorlessness

“This strange concept of colorless sculptures dates back to the Renaissance,” said archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann, head of the Antiquities and Asia departments at the museum and the curator of the show. Since beginning his research in Athens 40 years ago, Brinkmann has been studying the colors of ancient sculptures and brings his specialist expertise to the exhibition.

“At that time in Rome, there was a lot of construction happening and one sculpture after another was found. They no longer had any color.” So at first, no one knew any better, he explained to DW.

At the same time, the simplicity of colorlessness fit with the popular ideology of the period. “The colorless sculptures were used as a visual representations of the Enlightenment,” Brinkmann added.

Read more: Germany returns antiquities to Mexico

The lack of color made the figures lose their sensuality, said the archaeologist. “They were put, so to speak, on a pedestal.” Even the finding of the Laocoön and His Sons statue in Rome in 1503, which showed traces of color, could not shift assumptions about ancient statues being white. “It was deliberately looked over,” Brinkmann said.

But as the exhibition shows, colors were used diffusely in the ancient world, with the Greeks and Romans painting their sculptures, not only for decoration, but to elaborate the story of each work. Polychromy gave increased depth of cultural and artistic expression.

New findings — and a fascist backlash

The myth of colorlessness was further refuted during excavations in Pompeii in the 18th century. The finds made at that time showed undeniable remains of paint on numerous objects. Pompeii was destroyed by a volcanic eruption in 79 A.D. and the lava that poured over the city protected the finds and preserved their colors.

In the 19th century, large excavations on the Acropolis in Greece caused further upset. “That’s where the sculptures were found that the Persians had destroyed when they stormed the Acropolis in 480 B.C.,” Brinkmann noted.

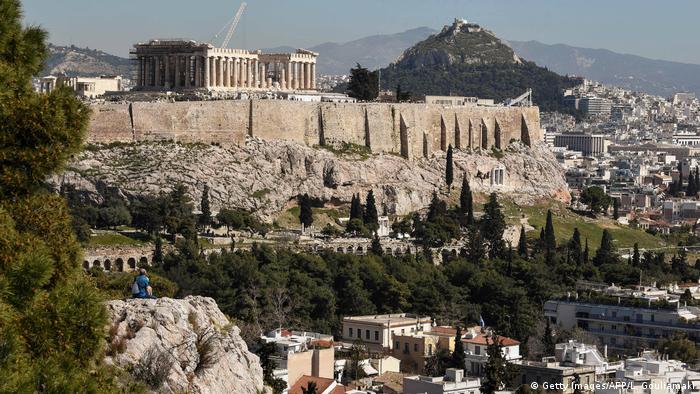

Many finds in Athens (pictured here) no longer had color. As a result, many originally thought they had always been white.

Many finds in Athens (pictured here) no longer had color. As a result, many originally thought they had always been white.

“When the Athenians returned to the city, they did not reassemble these overturned sculptures, but buried them under the sanctuary instead, which protected them. When archaeologists dug them up after two and a half thousand years in 1986-87, some of the colors were still fresh and dazzlingly beautiful,” said the archaeologist. So by the end of the 19th century it was clear: Antiquity was not white. It was colorful.

But with the rise of fascism in the 20th century, the tide turned again. The colorful figures of antiquity did not fit in with the aesthetics of dictators Mussolini, Franco, Hitler or Stalin. They were simply too sensual, says Brinkmann.

“One has to consider how much the loss of color reduces sensuality; how what is sexy about the antique statue becomes abstract when color is removed.”

The exhibition “Gods in Color” at the Liebieghaus Museum in Frankfurt features over 100 works in their original colors.

The exhibition “Gods in Color” at the Liebieghaus Museum in Frankfurt features over 100 works in their original colors.

In the exhibition, more than 100 objects are on display, including 60 reconstructions. The exhibition is a continuation of another held in Munich from 2003 that was shown in 30 cities worldwide. The current show will also travel to Naples, New York and Sydney, among other locations.

“Gods in Color” runs at the Liebieghaus Museu

True Colors

Archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann insists his eye-popping reproductions of ancient Greek sculptures are right on target

Dull is the eye that will not weep to see

Thy walls defaced, thy mouldering shrines removed

By British hands, which it had best behov’d

To guard those relics ne’er to be restored.

To this day, Greece continues to press claims for restitution.

The genius behind the Parthenon’s sculptures was the architect and artist Phidias, of whom it was said that he alone among mortals had seen the gods as they truly are. At the Parthenon, he set out to render them in action. Fragments from the eastern gable of the temple depict the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus; those from the western gable show the contest between Athena and Poseidon for the patronage of the city. (As the city’s name indicates, she won.) The heroically scaled statues were meant to be seen from a distance with ease.

But that was thousands of years ago. By now, so much of the sculpture is battered beyond recognition, or simply missing, that it takes an advanced degree in archaeology to tease out what many of the figures were up to. Yes, the occasional element—a horse’s head, a reclining youth—registers sharp and clear. But for the most part, the sculpture is frozen Beethoven: drapery, volume, mass, sheer energy exploding in stone. Though we seldom think about it, such fragments are overwhelmingly abstract, thus, quintessentially “modern.” And for most of us, that’s not a problem. We’re modern too. We like our antiquities that way.

But we can guess that Phidias would be brokenhearted to see his sacred relics dragged so far from home, in such a fractured state. More to the point, the bare stone would look ravaged to him, even cadaverous. Listen to Helen of Troy, in the Euripides play that bears her name:

My life and fortunes are a monstrosity,

Partly because of Hera, partly because of my beauty.

If only I could shed my beauty and assume an uglier aspect

The way you would wipe color off a statue.

That last point is so unexpected, one might almost miss it: to strip a statue of its color is actually to disfigure it.

Colored statues? To us, classical antiquity means white marble. Not so to the Greeks, who thought of their gods in living color and portrayed them that way too. The temples that housed them were in color, also, like mighty stage sets. Time and weather have stripped most of the hues away. And for centuries people who should have known better pretended that color scarcely mattered.

White marble has been the norm ever since the Renaissance, when classical antiquities first began to emerge from the earth. The sculpture of Trojan priest Laocoön and his two sons struggling with serpents sent, it is said, by the sea god Poseidon (discovered in 1506 in Rome and now at the Vatican Museums) is one of the greatest early finds. Knowing no better, artists in the 16th century took the bare stone at face value. Michelangelo and others emulated what they believed to be the ancient aesthetic, leaving the stone of most of their statues its natural color. Thus they helped pave the way for neo-Classicism, the lily-white style that to this day remains our paradigm for Greek art.

By the early 19th century, the systematic excavation of ancient Greek and Roman sites was bringing forth great numbers of statues, and there were scholars on hand to document the scattered traces of their multicolored surfaces. Some of these traces are still visible to the naked eye even today, though much of the remaining color faded, or disappeared entirely, once the statues were again exposed to light and air. Some of the pigment was scrubbed off by restorers whose acts, while well intentioned, were tantamount to vandalism. In the 18th century, the pioneering archaeologist and art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann chose to view the bare stone figures as pure—if you will, Platonic—forms, all the loftier for their austerity. “The whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is as well,” he wrote. “Color contributes to beauty, but it is not beauty. Color should have a minor part in the consideration of beauty, because it is not [color] but structure that constitutes its essence.” Against growing evidence to the contrary, Winckelmann’s view prevailed. For centuries to come, antiquarians who envisioned the statues in color were dismissed as eccentrics, and such challenges as they mounted went ignored.

No longer; German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann is on a mission. Armed with high-intensity lamps, ultraviolet light, cameras, plaster casts and jars of costly powdered minerals, he has spent the past quarter century trying to revive the peacock glory that was Greece. He has dramatized his scholarly findings by creating full-scale plaster or marble copies hand-painted in the same mineral and organic pigments used by the ancients: green from malachite, blue from azurite, yellow and ocher from arsenic compounds, red from cinnabar, black from burned bone and vine.

Call them gaudy, call them garish, his scrupulous color reconstructions made their debut in 2003 at the Glyptothek museum in Munich, which is devoted to Greek and Roman statuary. Displayed side by side with the placid antiquities of that fabled collection, the replicas shocked and dazzled those who came to see them. As Time magazine summed up the response, “The exhibition forces you to look at ancient sculpture in a totally new way.”

“If people say, ‘What kitsch,’ it annoys me,” Brinkmann says, “but I’m not surprised.” Actually, the public took to his replicas, and invitations to show them elsewhere quickly poured in. In recent years, Brinkmann’s slowly growing collection has been more or less constantly on the road—from Munich to Amsterdam, Copenhagen to Rome—jolting viewers at every turn. London’s The Guardian reported that the show received an “enthusiastic, if bewildered” reception at the Vatican Museums. “Il Messagero found the exhibition ‘disorientating, shocking, but often splendid.’ Corriere della Sera‘s critic felt that ‘suddenly, a world we had been used to regarding as austere and reflective has been turned on its head to become as jolly as a circus.'” At the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, Brinkmann’s painted reconstruction of sections of the so-called Alexander Sarcophagus (named not for the king buried in it but for his illustrious friend Alexander the Great, who is depicted in its sculpted frieze) was unveiled beside the breathtaking original; German television and print media spread the news around the globe. In Athens, top officials of the Greek government turned out for the opening when the collection went on view—and this was the ultimate honor—at the National Archaeological Museum.

An American showing was overdue. This past fall, the Arthur M. Sackler Museum at Harvard University presented virtually the entire Brinkmann canon in an exhibition called “Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture of Classical Antiquity.” Selected replicas were also featured earlier this year in “The Color of Life,” at the Getty Villa in Malibu, California, which surveyed polychromy from antiquity to the present. Other highlights included El Greco’s paired statuettes of Epimetheus and Pandora (long misidentified as Adam and Eve) rendered in painted wood and Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier’s exotic Jewish Woman of Algiers of 1862, a portrait bust in onyx-marble, gold, enamel and amethyst.

The palette of these works, however, was not as eye-popping as that of Brinkmann’s reproductions. His “Lion From Loutraki” (a copy of an original work dated circa 550 B.C., now in the sculpture collection of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen) displays a tawny pelt, blue mane, white teeth and red facial markings. That exotic archer (from the original at the Glyptothek in Munich) sports a mustard vest emblazoned with a pattern of red, blue and green beasts of prey. Underneath, he wears a pullover and matching leggings with a psychedelic zigzag design that spreads and tapers as if printed on Lycra. Unlike previously proposed color schemes, which were mostly speculative, Brinkmann’s is based on painstaking research.

My own introduction to Brinkmann’s work came about three years ago, when I was traveling in Europe and the image of a reproduction of a Greek tombstone in a German newspaper caught my eye. The deceased, Aristion, was depicted on the stone as a bearded warrior at the height of his prowess. He stood in profile, his skin tanned, his feet bare, decked out in a blue helmet, blue shinguards edged in yellow, and yellow armor over a filmy-looking white chiton with soft pleats, scalloped edges and a leafy-green border. His smiling lips were painted crimson.

Brinkmann led me first to a sculpture of a battle scene from the Temple of Aphaia (c. 490 B.C.) on the island of Aegina, one of the Glyptothek’s prime attractions. Within the ensemble was the original sculpture of the kneeling Trojan archer whose colorfully painted replica Brinkmann had set up for the photo shoot on the Acropolis. Unlike most of the other warriors in the scene, the archer is fully dressed; his Scythian cap (a soft, close-fitting headdress with a distinctive, forward-curling crown) and his brightly patterned outfit indicate that he is Eastern. These and other details point to his identification as Paris, the Trojan (hence Eastern) prince whose abduction of Helen launched the Trojan War.

At Brinkmann’s suggestion, I had come to the museum late in the day, when the light was low. His main piece of equipment was far from high tech: a hand-held spotlight. Under “extreme raking light” (the technical term for light that falls on a surface from the side at a very low angle), I could see faint incisions that are otherwise difficult or impossible to detect with the naked eye. On the vest of the archer, the spotlight revealed a geometric border that Brinkmann had reproduced in color. Elsewhere on the vest, he pointed out a diminutive beast of prey, scarcely an inch in length, endowed with the body of a jungle cat and a majestic set of wings. “Yes!” he said with delight. “A griffin!”

The surface of the sculpture was once covered in brilliant colors, but time has erased them. Oxidation and dirt have obscured or darkened any traces of pigment that still remain. Physical and chemical analyses, however, have helped Brinkmann establish the original colors with a high degree of confidence, even where the naked eye can pick out nothing distinct.

Next, Brinkman shone an ultraviolet light on the archer’s divine protectress, Athena, revealing so-called “color shadows” of pigments that had long since worn away. Some pigments wear off more quickly than others, so that the underlying stone is exposed to wind and weather at different rates and thus also erodes at different rates. The seemingly blank surface lit up in a pattern of neatly overlapping scales, each decorated with a little dart—astonishing details given that only birds nesting behind the sculpture would have seen them.

A few weeks later, I visited the Brinkmann home, a short train ride from Munich. There I learned that new methods have greatly improved the making of sculptural reproductions. In the past, the process required packing a statue in plaster to create a mold, from which a copy could then be cast. But the direct application of plaster can damage precious color traces. Now, 3-D laser scanning can produce a copy without contact with the original. As it happened, Brinkmann’s wife, archaeologist Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, was just then applying color to a laser reproduction of a sculpted head of the Roman emperor Caligula.

I was immediately taken by how lifelike Caligula looked, with healthy skin tone—no easy thing to reproduce. Koch-Brinkmann’s immediate concern that day was the emperor’s hair, carved in close-cropped curls, which she was painting a chocolaty brown over black underpainting (for volume) with lighter color accents (to suggest movement and texture). The brown irises of the emperor’s eyes were darkest at the rim, and the inky black of each pupil was made lustrous by a pinprick of white.

Such realistic detail is a far cry from the rendering of Paris the archer. In circa 490 B.C., when it was sculpted, statues were decorated in flat colors, which were applied in a paint-by-numbers fashion. But as time passed, artists taught themselves to enhance effects of light and shadow, much as Koch-Brinkmann was doing with Caligula, created some five centuries after the archer. The Brinkmanns had also discovered evidence of shading and hatching on the “Alexander Sarcophagus” (created c. 320 B.C.)—a cause for considerable excitement. “It’s a revolution in painting comparable to Giotto’s in the frescoes of Padua,” says Brinkmann.

Brinkmann has never proposed taking a paintbrush to an original antiquity. “No,” he stresses, “I don’t advocate that. We’re too far away. The originals are broken into too many fragments. What’s preserved isn’t preserved well enough.” Besides, modern taste is happy with fragments and torsos. We’ve come a long way since the end of the 18th century, when factories would take Roman fragments and piece them together, replacing whatever was missing. Viewers at the time felt the need of a coherent image, even if it meant fusing ancient pieces that belonged to different originals. “If it were a question of retouching, that would be defensible,” Brinkmann says, “but as archaeological objects, ancient statues are sacrosanct.”

A turning point in conservation came in 1815 when Lord Elgin approached Antonio Canova, the foremost neo-Classical sculptor, about restoring the Parthenon statues. “They were the work of the ablest artist the world has even seen,” Canova replied. “It would be sacrilege for me, or any man, to touch them with a chisel.” Canova’s stance lent prestige to the aesthetic of the found object; one more reason to let the question of color slide.

In the introduction to the catalog of the Harvard show, Brinkmann confesses that even he is a relatively recent convert to the idea that the painting of statues actually constituted an art form. “What that means,” he elaborates, “is that my perspective has been molded by 20th-century classicism. You can’t shake that off. It stays with you all your life. Ask a psychiatrist. You have to work very hard to adjust to a new way of seeing. But I’m talking about personal feelings here, not about scholarly conviction.”

Past attempts to colorize, notably by Victorian artists, were based mostly on fantasy and personal taste. Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s painting Pheidias and the Frieze of the Parthenon (1868-69) shows the Greek artist giving Pericles and other privileged Athenians a private tour of the Parthenon sculptures, which are rendered in thick, creamy colors. John Gibson’s life-size statue Tinted Venus (1851-56) has honey hair and rose lips. One 19th-century reviewer dismissed it as “a naked impudent English woman”—a judgment viewers today are unlikely to share, given the discreet, low-key tints Gibson applied to the marble. In the United States, C. Paul Jennewein’s king-size allegorical frieze of sacred and profane love on a pediment of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, unveiled in 1933, is more lavish in its use of color. The figures, representing Zeus, Demeter and other Greek divinities, are executed in showy glazed terra cotta. To contemporary eyes, the effect appears Art Deco, and rather camp.

While viewers today may regard Brinkmann’s reconstructions in the same light, his sculptures are intended as sober study objects. Areas where he has found no evidence of original coloration are generally left white. Where specific color choices are speculative, contrasting color re-creations of the same statue are made to illustrate the existing evidence and how it has been interpreted. For example, in one version of the so-called Cuirass-Torso from the Acropolis in Athens (the one in which the armor appears to cling like a wet T-shirt, above), the armor is gold; in another it is yellow. Both are based on well-founded guesses. “Vitality is what the Greeks were after,” Brinkmann says, “that, and the charge of the erotic. They always found ways to emphasize the power and beauty of the naked body. Dressing this torso and giving it color was a way to make the body sexier.”

But the question remains: How close can science come to reproducing the art of a vanished age? There is no definitive answer. Years ago, a first generation of inquisitive musicians started experimenting with early instruments, playing at low tunings on gut strings or natural horns, hoping to restore the true sound of the Baroque. Whatever the curiosity or informational value of the performances, there were discriminating listeners who thought them mere exercises in pedantry. When the next generation came along, period practice was becoming second nature. Musicians used their imagination as well as the rule books and began making music.

Brinkmann ponders the implications. “We’re working very hard,” he says. “Our first obligation is to get everything right. What do you think? Do you think some day we can start making music?”

An essayist and cultural critic based in New York City, author Matthew Gurewitsch is a frequent contributor to these pages.

spacer

‘Gods in Color’ returns antiquities to their original, colorful grandeur

Looking for “paint ghosts”

Artistic impressions

Most ancient pigments were derived from minerals, some of which were toxic. (Natural cinnabar, the most popular red color in the ancient world, for example, came from mercury.) To make paint, the pigments were mixed with binders made from common items such as eggs, beeswax and gum arabic.

“Most people have no idea that the originals were colored, and they are astounded by the reproductions,” said Dreyfus.

King Tut sculpture sold at Christie’s despite Egypt’s outrage

A 3,000-year-old sculpture of Tutankhamun was auctioned off by Christie’s for nearly $6 million, despite Cairo calling on the UK government to stop the sale. Egypt claimed the relic was illegally taken from the country.

UK-based Christie’s auction house sold an ancient sculpture of King Tut’s head for £4,746,250 ($5,969,904, €5,290,171) on Thursday. The organization did not share any information about the buyer.

Christie’s decided to go ahead with the auction amid protests from Egypt’s government and despite a small protest outside its London premises. Cairo has argued that the relic was smuggled out of Egypt and is still legally owned by the state.

“I believe that it was taken out of Egypt illegally,” Mostafa Waziri, secretary general of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities told the Reuters news agency. “[Christie’s] has not presented any documents to prove otherwise.”

Where does it come from?

International conventions prevent the sale of objects that are known to be stolen or illegally dug up. Egyptian officials asked the UK Foreign Office and UNESCO to intervene, but such interventions are only made if there is clear evidence to dispute legitimate acquisition.

Christie’s claimed it had performed “extensive due diligence” and “gone beyond what is required to assure legal title” of the piece.

Read more: Conserved glories of Tutankhamun tomb revealed

According to the auction house, the sculpture came from the private Resandro Collection of ancient art. It had allegedly been acquired from Munich art dealer Heinz Herzer in 1985, who bought it from Austrian dealer Joseph Messina in 1973-1974. The company says a member of German nobility, Prince Wilhelm Von Thurn und Taxis “reputedly” owned it before that.

The last point has been disputed by accounts from his niece and an art historian who told Live Science site that Wilhelm had very little interest in collecting art.

Heritage sold ‘like vegetables’

Talking to the AFP news agency from Cairo, former Egyptian Antiquities Minister Zahi Hawass said the statue was likely “stolen” in the 1970s from the Karnak Temple complex just north of the ancient city of Luxor.

“We think it left Egypt after 1970 because in that time other artifacts were stolen from Karnak Temple,” Hawass said.

A crowd of some 20 protesters gathered in front of Christie’s on Thursday, holding up placards saying that “Egyptian history is not for sale.”

“We are against our heritage and valuable items (being) sold like vegetables and fruit,” said Ibrahim Radi, a 69-year-old Egyptian graphic designer protesting outside Christie’s.

dj/sms (AFP, Reuters, AP)

At the time the Black Lives Matter campaign in the UK was drawing the national spotlight to the statues of slave traders, another activist was highlighting the way women are represented in civic statuary. “Just look at what you are being socialised to accept as normal…” says the activist’s placard, focusing on a monument outside the Trafford Centre in Manchester. It shows a seated man bathing his feet surrounded by a clutch of fawning semi-naked women. Another sign beside a statue in Iowa, US – of a bronze topless woman arching her back and holding her breasts as if to deliberately enhance her cleavage – reads: “Iowa as a mother figure offering nourishment to her children? Yeah.”

The placard bearer is ArtActivistBarbie, a Barbie doll posed in front of artworks and monuments, and the playful alter ego of Sarah Williamson, a senior lecturer at the University of Huddersfield. Williamson began the project as way to engage students with feminist ideas, and in particular the way women are portrayed in art. “This way, I can lead people gently into those conversations,” Williamson tells BBC Culture. “It’s a form of feminist ventriloquism – my voice, being spoken through a third party with AAB [ArtActivistBarbie] is the equivalent of a ventriloquist’s dummy.”

ArtActivistBarbie poses with a toy tiger in a parody of the 1889 painting Circe by Wright Barker, showing a topless woman surrounded by lions (Credit: Sarah Williamson/Twitter)

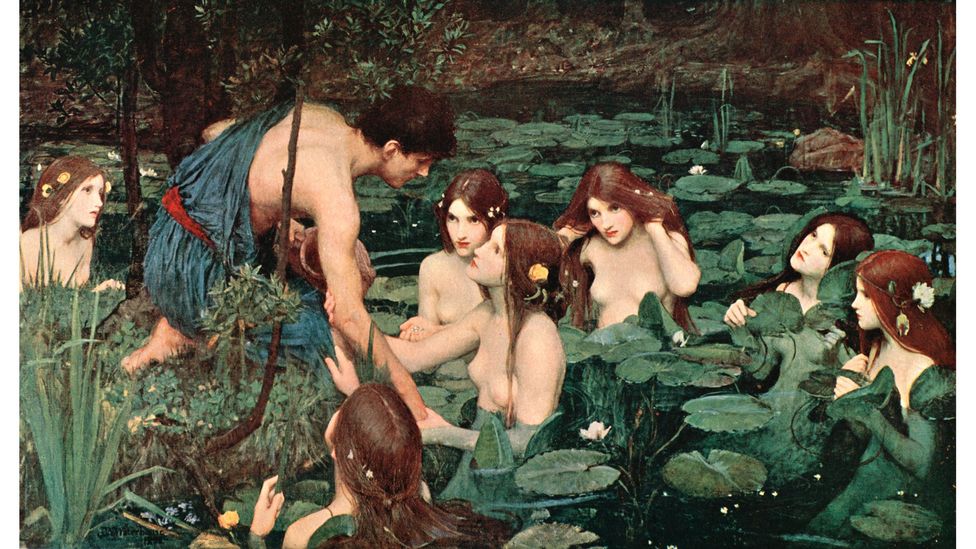

In a Twitter post, ArtActivistBarbie imagines the commissioning of the 1889 painting Circe by Wright Barker, which shows a topless woman surrounded by lions. “‘I’d like a seductive young beauty, half undressed, confined and with some big game,’ said the patron”, the Twitter post reads. “‘How about Circe, say with 5 or 6 tigers?’” said the artist. ‘Everyone will admire your scholarly interest in Greek Mythology.’” With her tongue firmly in her cheek, ArtActivistBarbie asks if this is the depiction of a classical scene or thinly veiled Victorian porn.

We have to learn to look the past and its faults in the eye – Mary Beard

The classics professor Mary Beard asked a similar question in her TV series Shock of the Nude, which aired earlier this year in the UK. The programme explored the many ways male artists have tried to justify the existence of naked women in their paintings: reclining nudes are depicted as innocently ‘caught’, half-bathing or somehow sleepily compromised in a state of undress.

So is what we are looking at art or pornography?

“That is a complicated question and anyone who thinks they know the answer should reflect a bit harder!” Professor Beard tells BBC Culture. “My line is that the boundary between art and pornography is always a treacherous one and the point about the past is that we have to see it both in its own terms and ours. We have to learn to look the past and its faults in the eye.”

A contentious issue

For more than 100 years, feminists have drawn attention to sexist attitudes that exist within the art world. In 1914, the suffragist Mary Richardson attacked Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus with an axe. The painting portrays Venus looking in the mirror, turned away from the viewer with her bottom at the centre of the canvas. Richardson claimed her protest was partly at the way men gaped at the painting, which hangs in London’s National Gallery.

In 1914 the suffragist Mary Richardson attacked Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus in protest at its portrayal of the female nude (Credit: Getty Images)

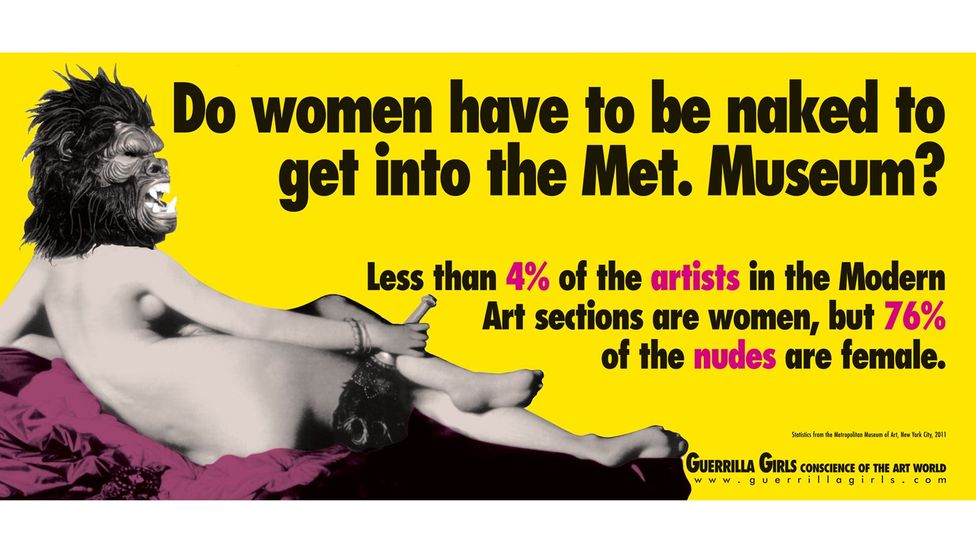

“Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?” shouted one billboard poster put up by feminist art activists Guerrilla Girls in the 1980s. At the time it seemed they did – less than 4% of artists in the modern art section of the museum were by women, but 76% of the nudes were female. With smart, cutting messages delivered via large-scale billboard works, the Guerilla Girls sought to name and shame the art world for its unapologetic disregard for women and other minorities in art.

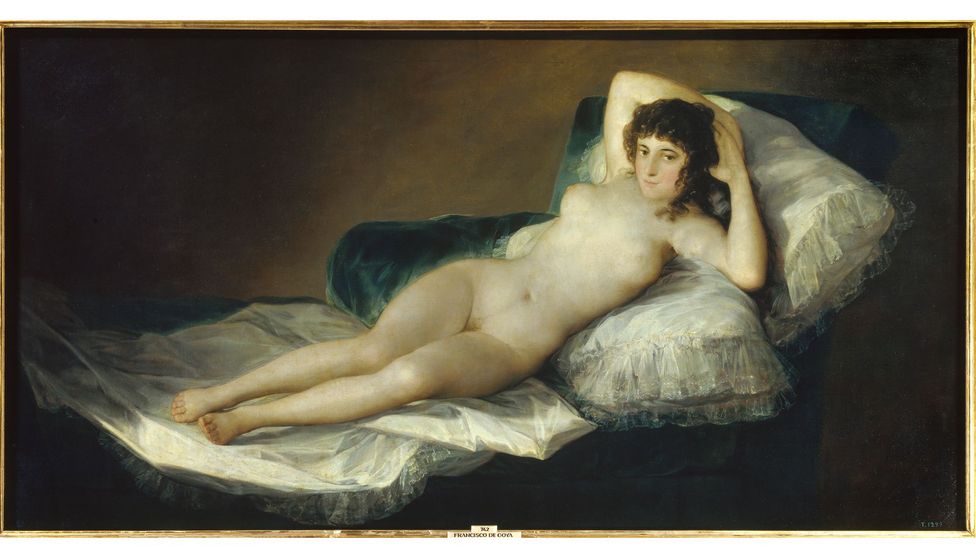

If you want, compare Goya’s Naked Maja to a Playboy centrefold and tell me the line is not blurred – Hans Maes

In 2018, British artist Sonia Boyce took a different approach when she staged a removal, in front of an audience, of Hylas and the Nymphs by John William Waterhouse from Manchester Art Gallery. The space on the wall, where the painting depicting a clutch of semi-naked young girls luring Hylas into a lily pond had hung, was left empty for a week. “My aim was to draw attention to – and question – the ways in which museums make decisions about what visitors see, in what context and with what labelling,” Boyce said after the move provoked a furious backlash with accusations of censorship, political correctness and feminist extremism. “Taking the picture down was about starting a discussion, not provoking a media storm.” It did both. The issue of art and pornography is a contentious one.

In the 1980s, feminist art activists Guerilla Girls famously asked ‘Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?’ (Credit: Guerilla Girls)

“The boundaries have always been blurred,” says Hans Maes, a lecturer in art history at Kent University who has written extensively on the subject. “It’s generally assumed that pornography has two key characteristics: it’s sexually explicit and its aim is to sexually arouse the viewer. Well, throughout history and across cultures you can find great works of art that share those very characteristics. Think of some of the mosaics in Pompeii, Kama Sutra sculptures or some of Gustav Klimt’s explicit drawings. If you want, compare Goya’s Naked Maja to a Playboy centrefold and tell me the line is not blurred.”

In 2014, performance artist Deborah de Robertis sought to make just this point by exposing herself in front of Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World painting in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris to reproduce the close-up image of a woman’s genitals. She was subsequently arrested for posing naked in front of Manet’s Olympia, also in the Musée d’Orsay. Her point was to raise the question: why is one representation of the human body defined as art and another as pornography?

Goya’s Naked Maja (above), Courbet’s The Origin of the World and Klimt’s explicit drawings are works that some historians and activists think ‘blur lines’ (Credit: Getty Images)

In the past, censorship of explicit images was often motivated by conservative and religious values and fears of moral corruption. By contrast, feminists who challenge objectifying sexual imagery want equal rights for women, and they fear the spread of objectifying images is detrimental to that cause. At the time of Boyce’s intervention in Manchester, a fourth wave of feminism was surging amid the wave of accusations against Harvey Weinstein and Jeffrey Epstein and others, and there was a surge of anxiety about how to deal with art made under different ethical conditions from our own.

You don’t have to look very far to find examples. Benvenuto Cellini insisted on using young virgins as models and ‘deflowering’ them once he had finished painting them. Eric Gill used his own daughters as models and sexually abused them. “We should perhaps distinguish between the context of appreciation and the context of creation,” Maes tells BBC Culture. “If we know that an artist abused women and his abusive attitudes are also manifest in the work, then that does affect the status of the work. The work itself will come to appear seedy and morally problematic, once you become aware.”

In 2018, the artist Sonia Boyce staged a removal of John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs from Manchester Art Gallery (Credit: Getty Images)

In the recent Jeffrey Epstein documentary on Netflix, one of the arresting police officers comments on the sheer volume of nudes on display in the sex offender’s mansion. In a gallery, similar nudes might be objects of admiration.

there’s a type of reverence to these institutions with their language of Old Masters and masterpieces which we absorb unconsciously and acceptingly – Sarah Williamson

“Well it does make you think,” agrees Sarah Williamson. “There are many paintings in our public art galleries of young pubescent girls, which make for uncomfortable viewing. The Syrinx by Arthur Hacker on display in Manchester Art Gallery for example, shows a young girl, naked, looking vulnerable and scared and it makes me feel very uncomfortable to view it. But there’s a type of reverence to these institutions with their language of Old Masters and masterpieces which we absorb unconsciously and acceptingly.”

‘Naked’ or ‘nude’?

Life drawing from nude models is still the mainstay of a fine art education and the vast majority of models are women; yet in the ‘sanctity’ of the life-drawing room, these women are not naked but ‘nude’, and they don’t strip but ‘disrobe’.

“But of course, the male gaze exists in the life-drawing class,” says Mary Beard, who herself posed as part of her investigation in Shock of the Nude. “There are various ways culture tries to remove it and those linguistic devices are used to try to desexualise the encounter. But it’s there.”

“Posing virtually was something I had hoped to avoid,” model Fra Beecher wrote in a blog about life modelling online during lockdown, which illustrated her own awareness of the male gaze. “I never allow photographs to be taken of myself when I am modelling. I wondered if it would be possible to reconcile my feelings regarding nude photography with my fear of appearing nude online.” Another life model expressed a blunter concern: that away from the confines of the life-drawing room, participants were free to masturbate rather than draw.

Another of ArtActivistBarbie’s subjects is Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, where a female nude is accompanied by two fully-clothed men (Credit: Getty Images)

Both women’s concerns show how fine the line between art and pornography is and how tricky trying to negotiate it is. Mary Beard’s claim in an interview that the nude is always in danger of being “soft porn for the elite” was met with abusive messages in the article comments and on Twitter. Like Boyce, she discovered that trying to start a discussion on the subject tends to inspire hostility rather than interest.

Which is why ArtActivistBarbie, subverting a plastic doll widely vilified by feminists for being a gender stereotype, was a stroke of genius on her creator’s part. “The issue is discussion and starting to view things differently,” says Sarah Williamson. “AAB provides a fun and playful way of doing this and, in doing so, trying to create a world in which there is more equality for women and where they are not just the subject of the male gaze.”

In one of ArtActivistBarbie’s most commented-on posts, she poses on the floor of a gallery in front of Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. In the first picture, Barbie is naked like the woman in the picture and her two male companions are fully clothed. But then the set-up is reversed and Barbie appears in her glad rags while the two men are naked.

It’s an interesting juxtaposition and one that certainly makes you think.

ArtActivistBarbie is on Twitter @barbiereports.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

spacer

In my personal opinion all art forms have the potential to be influence by demonic forces. Like all things, there is potential for good and for evil. Sadly, the arts have been highly corrupted by the fallen, and much of what we call art is really crafts taught by demons. That is why artists are almost always talking about their MUSE. Muses are spiritual entities worshiped by the Greeks and Romans. Look it up. If you are a follower of Christ, you should not be looking for a demonic spirit to guide you, and/or “INSPIRE” you. The word inspire means to allow a spirit inside you. To breathe in a SPIRIT.

God also told us not to make for ourselves any “Graven Images”. Some think that only relates to statues of gods or goddesses. But, the word says of ANYTHING that is on the Earth. Now, don’t get me wrong, I like beautiful things, and I use images in my articles to help people understand what they are reading. “A picture is worth a thousand words”. And I watch television and movies. I read books.

However, I try to be very careful what I put my eyes on. It is easy to get caught up by whatever spirit is animating the images. Even pictures of our own children can cause us to sin. We can become too focused on our children and not on GOD. So beware.