NGOs, 501C3, Large Corporations, Special Interest Groups, Environmentalists, Animal Rights Organizations, Children’s Research Hospitals, Cancer Centers, Heart Association, Emergency Aid Services, Universities etc.. and all PHILANTHROPIC Organizations; AKA Non-Government Entities should currently be under a very high degree of suspicion and scrutiny. CHARITY has been HIGHJACKED and given a bad reputation. The truly altruistic giving out of the love for our brethren has become a very, very rare commodity. Our society has fallen under the deception of the enemy and sadly humans have become self centered and self serving. Their thoughts and deeds are evil, motivated by money and notoriety.

Now, mind you, most of the people that are mixed up in the business of building the NEW WORLD GLOBAL ORDER, would say that they are working for the good of everyone. Trying to make the world a better place and solve all of the problems that plague us. lol…and they might even believe it. But, their vision is tainted because their hearts are dark.

We are living in the last days, and evil will wax worse and worse. I was just thinking the other day about the scripture regarding the world just before the flood.

Genesis 6:4-6

4 There were giants in the earth in those days; and also after that, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bare children to them, the same became mighty men which were of old, men of renown.

5 And God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually.

6 And it repented the Lord that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him at his heart.

We are not yet to where one would say that EVERY IMAGINATION OF THE THOUGHTS OF OUR HEARTS ARE ONLY EVIL CONTINUALLY… but we are getting awfully close. And, if the Elite are successful in their efforts to get the Graphene Oxide and Nanobots working to change our DNA and our personalities, removing our connection to GOD… then certainly, that will become the reality for the entire earth!

Today we are going to talk about NGO’s and their association with people and organizations with positions of wealth and power. They have been working for a very long time to build their connections and their finances. At this point they may be too powerful to stop. But, we must try.

space.

If you have not seen the following related posts, if you have not already seen them.

OUR NATION IS BEING INVADED… DO YOU CARE?

UN Immigration Compact

ORANGE THE WORLD

RETURN OF HUMAN SACRIFICE Part 3

WAR on the HORIZON? or much CLOSER

spacer

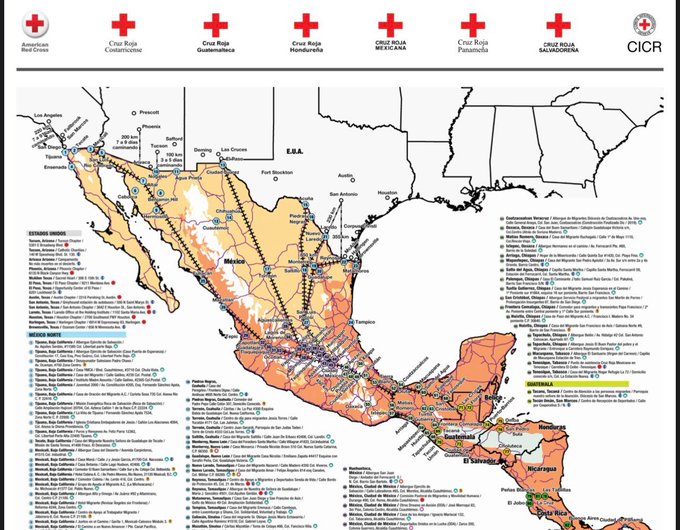

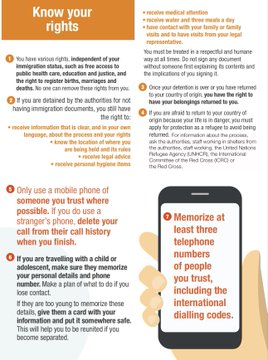

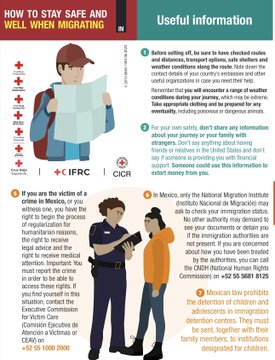

The American Red Cross and other non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have come under fire from some Republicans who allege they are helping migrants cross the southern border into the U.S.

Rep. Chip Roy, a Republican from Texas, wrote on social media that NGOs “are FACILITATING illegal immigration to the U.S., like the International Committee Red Cross, providing maps and information about traveling to the southern border.”

It comes as a large spike in migrants crossing into the U.S. at the southern border has increased frustration with President Joe Biden‘s immigration policies, and Republicans are seeking to make border security a major issue in the 2024 election.

Others echoed Roy’s sentiment, with one supporter of former President Donald Trump writing on the platform that that the Red Cross was to blame for “the invasion assistance at the southern border.”

Another wrote that the Red Cross and other NGOs “have been publishing maps/info on how to get from South America to our southern border. Stop giving money to these organizations now. Cut off all funding @WhiteHouse.”

Newsweek has contacted the American Red Cross and Roy’s office for comment via email.

Roy also called for the passage of the Secure the Border Act of 2023, which was introduced by Sen. Ted Cruz in September. The bill, which passed the House, would “defund NGOs receiving tax dollars to help traffic illegal aliens throughout the heartland,” according to a press release from Cruz’s office.

Biden is facing growing pressure both from Republicans and Democrats to curb the massive number of migrants crossing into the U.S.

spacer

New Fairness Meter!

New statistics about the millions of migrants released into the United States under President Joe Biden pose a concern for him as he turns to his reelection in 2024.

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has released more than 2.3 million migrants into the U.S. at the southern border under the Biden administration, The Washington Post reported, citing data from the Office of Homeland Security Statistics.

Mass releases of migrants are typically a final resort when border agents do not have the personnel or capacity to process migrants using normal procedures, the newspaper noted.

While the number is significantly less than the more than 6 million migrants taken into CBP custody during the same period, the data is likely to bolster criticism of Biden by Donald Trump, the frontrunner for the 2024 Republican nomination, and other Republicans on the campaign trial.

Biden has also faced criticism from Democrats over his administration’s policies regarding the southern border.

Biden “is staggeringly vulnerable on the immigration question” ahead of the 2024 election, said Thomas Gift, an associate professor of political science and director of the Centre on U.S. Politics at University College London.

“While the causes of the current dysfunction aren’t entirely his fault, and politics on both sides of the aisle make ‘comprehensive’ reform next to impossible, the sitting president is always going to take the blame for a surge in undocumented immigration,” Gift told Newsweek.

“With increasing numbers of center-left governors and mayors, even outside border states, expressing dissatisfaction over the White House’s handling of immigration, the issue could prove even more of a liability for Biden heading into 2024.”

On Friday, Biden hit out at congressional Republicans who he said have refused to consider his plan to “completely overhaul” the “broken immigration system.”

“They rejected my recent request for an additional $3.5 billion to secure the border and funds for 2,000 new asylum personnel and personnel and 100 new immigration judges so people don’t have to wait years to get their claims adjudicated, which they have a right to make a claim legally,” he said.

The president said that until Congress takes action, his administration is “going to work to make things better at the border using the tools that we have available to us now.”

Newsweek has contacted the Biden and Trump campaigns for comment via email.

spacer

spacer

If you follow the money trail it always leads to the same group at the end of the day ✡️ = 666 Esau-Edom as they pass laws in our governments that make it illegal for us to criticize anything they do however sick and heinous. And nearly all our politicians are involved in some way whether it’s insider trading or human trafficking pedophilia.

spacer

January 8th, 2024.

This is somewhere either in the waters off UK or mainland Europe…

spacer

November 29th, 2023.

GLOBALISTS ATTEMPT TO HIJACK AI SYSTEMS TO USE AGAINST THE AMERICAN PEOPLE AS GREAT AWAKENING HEATS UP We’ll also break down the establishment’s crackdown on free speech in the wake of migrant crimes in Europe, new documents exposing the massive scope of the Censorship Industrial Complex, and much more — tune in!

#news #infowars #politics #AlexJones #RonGibson

spacer

Amal at the The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland.

Amal at the The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland.

She’s called “Little Amal,” but the puppet depicting a 10-year-old Syrian refugee is not little at all. In fact, she’s a 12-foot-tall, international symbol of human rights who has already trekked more than 6,000 miles across 13 countries for a project called “The Walk.”

|

The name Amal comes from the verb עמל (amal), meaning to labor: |

| Amal Muslim meaningDerived from the three Arabic letters – alif, meem and lam – amal is a verb that means hope in at least three ways. The first is to be hopeful for something, the second is to desire or wish for something and the third is to expect or manifest for something to happen. |

As part of her month-long “Amal Walks Across America” tour from Boston to San Diego, which kicks off Thursday, she’ll spend three days in the D.C. region (from Sept. 17-19), where more than two dozen local arts organizations, businesses, and NGOs are planning performances and interactive events to welcome her.

She’s already met Pope Francis, Jude Law, and Ukrainian refugees in Poland. The production team behind the project has even hinted at a potential White House visit — or at least a stop in front of the gates to the White House complex.

But besides her meetings with people in power, children are the project’s target audience.

Kids seem to love Amal, despite her dramatic appearance. Some are initially shocked or even frightened by how large she is–until they make eye contact with her, says Khadijat Oseni, associate artistic director of The Walk Productions, the main production company behind Amal.

“It’s magical, and the reactions run the gamut,” Oseni says. “You’re not expecting to encounter a 12-foot puppet coming down the city street, so that is the beauty of the mechanism that is Amal. And kids inherently understand her.”

The large puppet is operated by three to four puppeteers at a time; one for each arm, one for her back, and another on stilts who controls her torso and facial movements. A team of nine puppeteers travels with her, and she can travel roughly 0.7 miles at a time. (The South Africa-based Handspring Puppet Company designed and built Amal.)

AMAL WALKS ACROSS AMERICA.

ONE LITTLE GIRL. ONE BIG HOPE.Little Amal will journey 6000 miles this fall from Boston to San Diego, where she will be welcomed by 1,000+ artists at 100+ events in 35 towns and cities across the United States. pic.twitter.com/KaXowc5u2S

— Little Amal (The Walk) (@walkwithamal) May 31, 2023

spacer

Amal means “hope” in Arabic. She’s based on a character in Joe Murphy and Joe Robertson’s play, The Jungle, which details life inside a refugee camp. Initially created to represent the impact of the Syrian civil war that’s now more than 12 years in, she’s come to embody the millions of children who have been displaced due to conflicts worldwide.

Hundreds of philanthropic organizations and global foundations have funded and supported the project, including the Bezos Family Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, and the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art. While it’s free to walk with Amal, she has already inspired thousands in donations; the Amal Fund has raised more than $330,000 toward a $5 million goal to provide food, shelter, and medical care to refugees around the world.

Amal’s creators hope her trip to the U.S. will continue to expand public perception of what it means to be a refugee, factoring in people who’ve been displaced by climate change and gentrification. “Through the lens of art, we’ve found that this is the most effective way of stretching perspectives, hearts, and minds,” says Oseni.

“Our hope for Amal is that she can spur conversations in communities across the country around the important role of refugees and newcomers in writing the ongoing story of the United States,” Amir Nizar Zuabi, artistic director for The Walk Productions, said in a statement.

Amal’s first trip to the U.S., a visit to New York last fall, was accompanied by a piece performed by the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and its children’s chorus.

While she’s in the nation’s capital, Amal will walk to a soundtrack provided by local musicians. Washington Performing Arts, Shakespeare Theatre Company, Arena Stage, Planet Word, and multiple Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) are some of the groups involved in the performance elements of her visit.

Little Amal in Folkestone, England.Igor Emerich / The Walk Productions

Amal’s journey in D.C. will conclude with a walk through a “sea of emergency blankets” down Pennsylvania Avenue, from Freedom Plaza to Capitol Hill, where she’ll present a collection of shoes “evoking the stories of millions of children on the move who seek safety and across borders.”

spacer

October 1st, 2023.

WHO, mRNA, and YOU: How the Big Pharma and NGO-Driven Agenda Is Our Genocide

spacer

MODERN MONEY LAUNDERING, Philanthropy and Non-Government Agencies NGOs

There are several reasons why criminals choose charities to launder money. They’re trusted by the general public and have certain privileges (e.g., tax exemptions). Moreover, some charities work internationally, which means that they may deal with high-risk countries, where it’s difficult to detect criminal activity. This combination of factors makes charities a favorable route for illicit funds.

In recent years, more and more charities are being implicated in financial scandals. This is particularly the case since the pandemic, which has made 65% of charities in the UK feel at greater risk of fraud. In 2021 alone, UK charities lost £8.6 million due to fraud.

Misuse of funds

A charity’s funds can be misused by criminals to make illicit transactions, investments, purchases, etc.

Misuse of charity resources

A criminal can infiltrate a charity—for instance, as an employee—to gain access to its assets and launder money through the organization.

Imposter charity

Criminals can pretend to be an existing charity to trick donors and launder money.

Shell charity

Criminals can establish a completely new charity that appears to be legitimate but is instead a front for money laundering.

Examples of charity money laundering

Recently, a charity called the “American Cancer Society of Michigan” applied to the IRS to become tax-exempt. This charity turned out to be fake, yet was still approved by the IRS. The person behind this scheme also founded 76 other fake charities in order to evade taxes.

In 2019, a UK man was sent to prison for 10 years for selling counterfeit supplements and laundering over £10 million through a charity run by him—Chabad UK.

These examples show how charities can be overlooked by regulators and why financial institutions need to verify the charities they work with. SOURCE

spacer

Forwarded:

FallCabal

THE SEQUEL TO THE FALL OF THE CABAL – PART 7, PHILANTHROPY OR MONEY LAUNDERING January 25th, 2021.

In this episode, we’ll dive into some of the (over 5,500!) NGOs that have been set up solely to execute the UN’s evil goals. These so-called philanthropic institutions are tax-exempt. They do not need to disclose their donors. They move millions (even billions!) of dollars around, from mother to sister company, to yet another subsidiary, without any legal control or obstruction whatsoever in this massive money laundering scheme. Let’s examine what ‘philanthropy’ truly means…

By Janet Ossebaard & Cyntha KoeterMusic: Alexander Nakarada,

spacer

This discussion examines the increasing influence of NGOs in global politics and focuses specifically on the role of development NGOs and the way in which they have challenged traditional understandings of state sovereignty. The discussion focuses on development NGOs in order to understand how many such organisations have taken on roles which were traditionally seen as the preserve of the nation state, being directly involved in healthcare provision, infrastructure development and educational provision. The discussion begins with a look at the increasing importance of NGOs in international development before highlighting how this has then led to them challenging state providers in terms of influence. The final two sections of the discussion cast a critical eye on the issue and examine the extent to which these developments have directly challenged state sovereignty and also the extent to which this should be seen as a problem.

The increasing influence of NGOs in global politics is something which has taken off in the post-war years (Weber 2010). Increasingly, the trend has reached such significant proportions that international relations theorists have argued that many traditional theories of international relations such as realism are now no longer relevant in light of these increasingly important global institutions (Weber 2010). As globalisation has gathered pace, and media coverage has become ever more comprehensive the number of NGOs which now have a truly global reach has grown dramatically (Green 2008). Organisations such as Oxfam now have a comprehensive global reach and an institutional and logistical capability which makes them one of the best equipped organisations in the world (Green 2008). Both Green (2008) and Chang (2003) argue that this professionalisation of what were once small charities run largely by well-meaning volunteers (or frequently religious organisations), has fundamentally changed the capabilities of what these organisations are able to achieve. By logical extension, this enhanced capability therefore, gives such organisations a much greater scope and power which inevitably results in enhanced political power and relevance. A key positive is that such organisations are now able to achieve far more than was ever thought possible less than a century ago. However, the downside for some is that this power is frequently not coupled with democratic accountability and responsibility…

…Conclusion

In conclusion, it can therefore be argued, that the rise in power of NGOs has certainly coincided with declining sovereignty in many of the world’s poorest countries and indeed in some of the wealthiest as well. However, the arguments examined above show that to solely blame NGOs for this decline in sovereignty is likely to be wrong. Indeed, much of the evidence suggests that the decline in sovereignty has been pushed much more by organisations such as global corporations and particularly global governance institutions which have comprehensively challenged state power in many institutions. That said, it must also be acknowledged that many of the larger NGOs have evolved into very powerful institutions which have directly challenged state power. To the extent that this trend is likely to continue, it must therefore be acknowledged, that NGOs have contributed to a decline in state sovereignty but also that they are certainly not the root cause of this decline. True, it is the GLOBALISTS and THE AGENDA FOR WORLD DOMINANCE that uses the NGO’s to further their cause.

Civil society conflict: The negative impact of International NGOs on grassroots and social movements

Author: Jacqueline Gilchrist

When considering the optimal way to mitigate poverty in the Global South, proposed solutions often involve international non-governmental organizations (INGOs). INGOs can be based in various countries, but an abundance of these are based in the Global North. These organizations tend to focus on implementing short-term, tangible projects. It is generally assumed in the Global North that these compassionate organizations will enter communities, carry out development programs, and then leave having addressed poverty; and it is for this reason that numerous donors in the Global North pour their money into INGOs. Moreover, INGOs often collaborate with existing local grassroots or social movements. According to journalist Augusta Dwyer, these movements are “made up of impoverished people who have joined together to struggle for some concrete goal.” Such movements typically begin their activities by focusing on protest and resistance. Eventually, these movements take on activities similar to those carried out by INGOs. When an INGO attaches itself to a social or grassroots movement, this arrangement can produce numerous benefits, like increased funding and raise international awareness.

On the flipside, there is a risk that INGO involvement will dilute local demands in order to fit international agendas. Alternatively, INGOs might focus on one specific objective, while ignoring others that may be equally important for the movement’s cause. I argue that relationships between INGOs and movements by and for impoverished communities in the Global South are often structurally harmful, as they promote external interests, are too short-sighted, and often disempower the poor.

One of the primary reasons that grassroots and social movements accept the help of INGOs is for the purposes of funding. While the individuals behind these movements may devise creative solutions to their communities’ problems, they often lack the resources to implement their ideas. As such, these individuals often seek the help of INGOs to kick-start their movements. For instance, INGOs are often voluntary by nature and have no source of income other than donor funding. Accordingly, INGOs have a certain level of accountability to these external donors. In addition, these donors typically expect a measurable result from the INGO if they are to continue donating to the organization. This dynamic may lead to NGOs implementing the agenda of their donor’s, rather than necessarily creating lasting and equal relationships within the community. As scholar J-E Noh writes, INGOs are all-too frequently losing their charitable, volunteer-oriented basis and instead consist primarily of “donor-driven programs and business-like changes”. Since many of the donors to these INGOs come from the Global North, this situation may constitute a new, growing dependency on the Global North. This dependency can be harmful to the grassroots movements, as it frequently results in more “Western-style,” capitalist solutions to problems of poverty, rather than local solutions by and for the affected community. Nonetheless, donor-dependency dynamics are not limited to the Global North. In India, for example, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are frequently linked to state institutions. As a result, while the social and grassroots movements seeking to partner with NGOs contest the state’s power, NGOs are themselves influenced by the state. The conflict of interest in these scenarios are clear, and can have detrimental results to the success and continuation of the grassroots and social movements against government policies.

There are widespread fears that INGOs are increasingly taking on a corporate character, due to the requirements of funding. Specifically, concerned individuals fear that corporatization will cause INGOs to favour donors over the impoverished communities whom they are meant to be helping. As a consequence, these organizations will little attachment to the community. INGOs therefore tend to create programs that have short-term, Band-Aid solutions, consequently sustaining poverty at a systemic level.

Additionally, the activities of INGOs are often project-focused. That is, INGOs seek to achieve one concrete goal. Once an INGO achieves this goal, they move on to another project, usually in another community. This approach may be effective in certain scenarios, particularly those of humanitarian and emergency aid. However, this project-based strategy is not as effective in empowering the poor and powerless over time. The empowerment of vulnerable groups is a long process. INGOs will often only take on one small portion of this large, interconnected challenge. An example of this is described in Dwyer’s 2011 book “Broke but Unbroken”. Here, a member of a grassroots movement states that a “partner” INGO only took on one very tangible project, while his movement “struggles for long-term issues that can last a whole lifetime.” Indeed, grassroots and social movement are inherently rooted in the interconnectedness and the causes of poverty in different communities. Although social and grassroots movements are often formed as a result of one particular problem, they do not, in Dwyer’s words, “abandon a movement once they’ve won what they set out to win but stay to fight for others.” In this sense, they very much differ from INGOs.

Abstract

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) were once considered as altruistic groups which aim was to impartially influence public policy with no vested interests. Nevertheless, this perception has changed. They are increasingly perceived as groups that prioritize their own ideologies or that respond to the interests of their donors, patrons, and members rather than to those of the groups they represent. This article discusses the politics of NGOs in the present changing globalized world as agents concerned with social and environmental change as much as with their own causes. It argues that numerous NGOs are as much a part of national and international politics as any other interest group and that their practices and activities are not always in the search of a good society or the common good.

Final Thoughts

NGOs have contributed to policy-making on critical issues. However, serious weaknesses have been exposed in the sector in terms of accountability, transparency, and ability to address equity concerns. These have resulted in a growing skepticism in the international community regarding their performance and have shifted the previously favourable global opinion of the NGO sector to a more critical one that questions even their legitimacy. Rather than a ‘choice and voice’ for the people, NGOs are now often regarded as primarily supportive of themselves and their agenda, along with that of their donors in many occasions. In the end, they seem to be no more than groups of individuals organized for multiple reasons that include human aspirations and self-interests that prevail over the search for the common good. While they remain key players in the development arena globally, they have lost the favourable view once held uncritically by the international community.

For years, governments and private-sector groups, mostly international, have had to justify their decisions and policy choices to a growing number of critical NGOs who claimed to represent the interests of the poor and marginalized, the environment, or gender equality. From their side, NGOs have not had to justify their decisions to anyone. Because the end objective in society should be the common good, it is time for all parties to improve their accountability and transparency, creating the space for norms and developing standards where there have been few. The pressure from NGOs has been so influential that it has resulted in more accountability and transparency in government and private-sector actors, although not necessarily in the NGOs themselves yet. This should be the next step.

spacer

Hundreds of these organizations have no choice but to do the bidding of foreign governments.

To fulfil their vision of how Israel should conduct its affairs and eventually arrive at a two-state solution, many Western countries actively interfere in Israeli politics. They do so directly through diplomatic channels and indirectly by funding Israeli NGOs that agree with their agenda.

Western governments and the NGOs they’ve enlisted have engaged in everything from aiding and abetting the construction of illegal Bedouin settlements to destroying archaeological discoveries that prove the Jews are Israel’s indigenous people.

More recently, this government-NGO nexus has rejected and protested against the Netanyahu government’s proposed judicial reforms. U.S. President Joe Biden has gone so far as to condition American support for Israeli-Saudi normalization on this purely domestic issue.

The current Israeli government rightly views all this as a threat to its sovereignty. Thus, it recently introduced the Nonprofits Law, a bill that would curb foreigners’ ability to exploit Israeli NGOs by taxing 65% of the NGOs’ foreign receipts.

Western countries, naturally, have violently objected to the bill. Following the swift eruption of outrage, the Netanyahu government caved and shelved the bill.

The governments that objected to the Nonprofits Law claim to be acting in Israel’s best interests. They assert that they are protecting Israeli civil society and thus Israel’s democracy.

“A vital and strong civil society is crucial for every democracy,” tweeted Sweden’s Ambassador to Israel Erik Ullenhag. He claimed, “The draft bill on NGO taxation would severely limit Israeli civil society.” The French, Dutch, Norwegian, Danish, Irish and Belgian embassies in Israel echoed this ostensible concern for Israel’s civil society.

These governments and their representatives in Israel have it backwards. The Nonprofits Law, which would have limited only that portion of civil society funded by foreign governments, would have bolstered, not weakened, Israel’s civil society.

Civil society, by definition, excludes government actors. It is defined as a “third sector,” separate from government and business. It is intended to act as a check on both. By pumping hundreds of millions of dollars into left-leaning NGOs that represent a small proportion of Israeli society, foreign governments are effectively inflating the influence of foreign-funded NGOs at the expense of domestically funded NGOs. This undermines Israel’s home-grown civil society.

In much of the West, NGOs have long since ceased to be independent of governments. They are now effectively agents of those governments and are sometimes called GONGOs—“government-organized non-governmental organizations.” GONGOs are set up or sponsored by governments in order to further those governments’ political interests. This is, at best, an empty mimicry of civil society.

Many of Israel’s foreign-funded NGOs are GONGOs. While the leaders of some Israeli NGOs are in complete agreement with their foreign paymasters, it is likely that others are reluctant participants. They need to reorder their priorities and adapt their policies in order to meet the demands of their foreign paymasters.

Such manipulation is very widespread in Israel. As noted by Kerem Navot, an organization that monitors and researches Israeli land policy in Judea and Samaria, foreign governments provide the vast majority of funding for left-wing NGOs.

NGOs that defy their funders face extinction and the loss of their employees’ livelihoods. Thus, as a practical matter, most have no choice but to do what they’re told.

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel inadvertently confirmed this near-total dependence on foreign governments. Passage of the Nonprofit Law, it said, could lead to the “literal collapse of dozens and perhaps hundreds of NGOs.”

From the perspective of Israelis who want Israeli policies to be based on the views of Israelis, this proves that hundreds of Israeli NGOs are doing the bidding of foreign governments. These NGOs are, in effect, a Trojan Horse.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu failed in his latest effort to curb foreign funding of NGOs, just as he failed in his 2017 attempt to ban all such foreign funding. But as long as he aspires for Israel to be a full-fledged sovereign state, he should not stop trying.

spacer

NGOS IN AFRICA: A TAINTED HISTORY

New African Magazine

From Oxfam, Save The Children, and this week, to Irish rocker’s Bono’s ONE Campaign, scandal after scandal continue to hit the Non Govermental Orgarnisations ( NGOs) and the aid sectors – amid reports that the UK’s charities’ watchdog has so far received 80 current and historical cases of safeguarding concerns. Back in 2005, we comprehensively looked at the issue in our bumper Cover Story in which we asked – What Are NGOs Really Doing In Africa? In this analysis – Firoze Manji and Carl O’Coill – trace and dissect the history of the rise of NGOs in Africa. You may need to read this while sitting down.

In many African countries, real per capita GDP has fallen and welfare gains achieved since independence in areas like food consumption, health and education have been reversed. The statistics are disturbing. In sub-Saharan Africa as a whole, per capita incomes dropped by 21% in real terms between 1981 and 1989. Development, it seems, has failed. This has been the context in which there has been an explosive growth in the presence of Western as well as local NGOs in Africa.

Today, NGOs form a prominent part of the “development machine”, a vast institutional and disciplinary nexus of official agencies, practitioners, consultants, scholars, and other miscellaneous experts producing and consuming knowledge about the “developing world”.

spacer

Haiti: A Republic of NGOs?

United States Institute of Peace

Is Haiti a Republic of NGOs?

spacer

“The world of NGOs must be exposed,” Warns Judit Varga

“In Brussels, democracy has simply been stolen and the EU is run by NGOs. Big internationally funded NGOs are also holding politicians hostage. And whether you look at the media or at the NGO officials, you see no difference.” Judit Varga, the outgoing Justice Minister, who will lead the governing parties’ list for the 2024 EP elections, told Demokrata.

“In Brussels, democracy has simply been stolen and the EU is run by NGOs. Big internationally funded NGOs are also holding politicians hostage. And whether you look at the media or at the NGO officials, you see no difference.” Judit Varga, the outgoing Justice Minister, who will lead the governing parties’ list for the 2024 EP elections, told Demokrata.

We have to get rid of this in Europe, the politician continued. “The Hungarian courage to expose them can help do this. Let us say you are an NGO, you get a lot of money for having a significant media presence, you pay MEPs to post your messages on social media, because that way you can create a kind of illusion. But that doesn’t make it true.”

The fight against NGOs will be particularly important in the future, and the NGO world needs to be exposed, Judit Varga stressed, who believes this also needs to be made a campaign issue. Just because someone says they are an NGO, does not mean they represent society, she explained. According to the rules of democracy and the rule of law, in political forums,

society is represented by those who run for election according to party political rules, who measure themselves and reach a threshold of support.

And those, of course, who have complied with transparency rules, party funding rules, and who do not have a big voice just because they are paid continuously, for example through the Open Society Foundations network.

On the question of what the composition of the European Parliament will be next summer, the Minister said:

“I would rather start from the point of view of what we should do to ensure that the balance of power is in our favor in the vote next summer. What is certain is that

the polls, whether we are looking at internationals or Hungarians, are pointing to a shift in the conservative-sovereigntist direction.”

This does not yet mean an absolute majority, but the balance of power suggests that there could be many MEPs who come largely from the conservative, sovereigntist side of the political spectrum, but who do not belong to any of the classical party families, she added. It is clear from personal encounters, but also from reading comments on the Internet, that there are many voters in Europe who are not appealing either to the parties of left-wing progression or to the overly liberal populists, because they do not provide the answers that the silent majority wants, for example on migration, gender issues, and other important social matters, Judit Varga elaborated.

The situation is different here in Hungary. Fidesz-KDNP has answers to the most important questions that the vast majority of society, far beyond the support of the party alliance, agrees with. Be it the importance of the homeland, the nation, family policy issues, the protection of children, migration, and so on,”

the Minister recalled.

Meanwhile, the NGO-held center in Brussels seems oblivious to the reality of what Europe is all about. There is the issue of the migration package. Quotas, migrant ghettos, a sanctions mechanism for countries that do not accept newcomers, while in France, it seems as if a gloomy prophecy is already coming true – she concluded.

spacer

World Economic Forum

Wikipedia

The World Economic Forum (WEF) is an international non-governmental organization for public – private sector collaboration[1] based in Cologny, Canton of Geneva, Switzerland. It was founded on 24 January 1971 by German engineer Klaus Schwab.

The foundation’s stated mission is “improving the state of the world by engaging business, political, academic, and other leaders of society to shape global, regional, and industry agendas”.[2] The Forum programmatically promotes a multi-stakeholder governance model, stating that the world is best managed by a self-selected coalition of multinational corporations, governments and civil society organizations (CSOs),[3] which it expresses through initiatives like the “Great Reset”[4] and the “Global Redesign”.[5]

The foundation is mostly funded by its 1,000 member multi-national companies.[6]

The WEF is mostly known for its annual meeting at the end of January in Davos, a mountain resort in the eastern Alps region of Switzerland. The meeting brings together some 3,000 paying members and selected participants – among whom are investors, business leaders, political leaders, economists, celebrities and journalists – for up to five days to discuss global issues across 500 sessions.

Aside from Davos, the organization convenes regional conferences. It produces a series of reports, engages its members in sector-specific initiatives[7] and provides a platform for leaders from selected stakeholder groups to collaborate on projects and initiatives.[8]

The World Economic Forum and its annual meeting in Davos have received criticism over the years, including the organization’s corporate capture of global and democratic institutions, its institutional whitewashing initiatives, the public cost of security, the organization’s tax-exempt status, unclear decision processes and membership criteria, a lack of financial transparency, and the environmental footprint of its annual meetings.

Sex abuse claims expose a culture of large NGOs wrapped in self-delusion.

The Guardian

Feb 24, 2018 —

spacer

The backlash against NGOs

Is it safe to grant a mandate to change the world to unelected organisations which operate under the banner of democracy, but which answer only to their directors, fundholders or members, and are far less transparent than most political parties? The same question is asked by NGOs of multinational corporations. But are the champions of the oppressed in danger of mirroring some of the sins of the oppressor? More important, how responsible have NGOs been in wielding their newly-won power?

Filling the global gap

The turning-point in the fortunes of NGOs was the UN earth summit in Rio in 1992, where environmental pressure groups were directly involved in drawing up a treaty to control emissions of greenhouse gases. They had access to the official working groups and served on government delegations, and through lobbying and use of the media they greatly accelerated the negotiating process. For the first time, NGOs had moved from the spectators gallery to the decision-making table. In January, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, representatives from 15 NGOs were for the first time invited to take part in debates on globalisation.

As finance and production become more global and increasingly important decisions are taken at an international level, where there is no political machinery to deal with citizens’ concerns, NGOs are filling the “democratic deficit.” “The same factors that have been eroding nation-states have also been promoting NGOs,” says James Paul, executive director of the Global Policy Forum in New York. “NGOs have become the vehicle for the expression of popular concern in this transitional period as nation-states weaken and politics is not yet established at the transnational level.”

The effectiveness of NGOs has been assisted by the internet. The collection and communication of large volumes of information is no longer the domain of governments alone. Pressure groups can link up across the world without moving from their desks—as the demonstrations in Seattle showed. “The difference between what you can do now and what you could do 15 years ago is enormous,” says Jessica Mathews, co-founder of the World Resources Institute. “In the 1980s at the WRI it was impossible to deal with people in Africa—the phones didn’t work well enough. The relative lowering of the cost of communication has made a huge difference for NGOs domestically and internationally.”

Even if you exclude domestic NGOs (which number in the millions) it is difficult to estimate how many NGOs there are. One source estimates that during the 1990s the number of international NGOs increased from about 6,000 to more than 26,000. Many of the larger ones, such as Care, control budgets worth more than $100m. Membership of the Worldwide Fund for Nature has increased nearly tenfold, to 5m, since the mid-1980s; it has 3,300 staff and an annual budget of more than $350m. Greenpeace has nearly 2.5m members and 1,142 staff. Amnesty International has 1m members in 162 countries. Friends of the Earth has 1m members in 58 countries. Membership of Britain’s Royal Society for the Protection of Birds has risen from 10,000 in 1960, to 1m today. Several NGOs have stepped in to take up roles that the UN or national governments might once have been expected to fill. About 10 per cent of all development aid is channelled through NGOs, and that figure will rise. In the human rights field, the UN acknowledges that its entire programme would fall apart without the information-gathering and campaigning resources of NGOs. In his study NGOs and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1998), William Korey notes that when the Declaration was approved by the UN in 1948, 41 NGOs held consultative status. It has now been granted to more than 1,000. Amnesty International alone is better resourced than the human rights arm of the UN.

The big international NGOs cover three main areas: human rights, development and the environment. Some specialise in distributing aid, others in campaigning and propaganda. As advocates for change, NGOs are often far more effective than governments or international bodies: they can mobilise public opinion through the media and embarrass officialdom or businesses into action without fear of retaliation.

The single issue problem

But there is another side to the NGOs. International civil society is not a homogeneous forum of altruistic groups fighting for a common outcome. As Jessica Mathews wrote in Foreign Affairs in 1997: “For all their strengths, NGOs are special interests. The best of them… often suffer most from tunnel vision, judging every public act by how it affects their particular interest. Generally, they have limited capacity for large-scale endeavours, and as they grow, the need to sustain growing budgets can compromise the independence of mind that is their greatest asset.” The fact that NGOs do not have to think about policy trade-offs or the overall impact of their causes can even be harmful. “A society in which the piling up of special interests replaces a single strong voice for the common good is unlikely to fare well.”

NGOs are like political parties in that they depend on their members for funding and answer to them for their policies. Since they could not survive without their “grassroots,” much of their campaigning is geared towards expanding this base, sometimes in competition with other organisations. But NGOs are unlike political parties in that they are not accountable to the electorate. However much they claim to speak for the public, their main responsibility is always to themselves.

A tendency to play to the gallery, and straightforward infighting, is common among some NGOs desperate to maximise membership. This is most marked in the environmental sector. “There isn’t a green movement,” says Pete Wilkinson, a director of Greenpeace UK during the 1980s. “It’s a bunch of self-interested organisations which generally don’t get on.” Tom Burke, director of Friends of the Earth from 1975-79, then adviser to three secretaries of state for the environment, and now an environmental policy consultant to BP and Rio Tinto, warns of a ghetto mentality. “One of the dangers is that you really do think you’ve got all the answers and anyone who doesn’t agree with you is an idiot or evil.”

Typical divisions include that between the Humane Society of the US, which wants to preserve wildlife at all costs, and organisations such as the Worldwide Fund for Nature which favour sustainable management and community involvement; or the division between advocates of a logging ban in North American forests and those promoting wood as a sustainable resource which could replace fossil fuels. Some NGOs measure their success in terms of new regulations passed by Congress or parliament; others favour decentralisation and a more market-orientated approach. And some green groups openly demonise others. In 1993 Greenpeace published a book of environmental enemies which included other organisations fighting for the same goals but using methods of which it did not approve.

For organisations which are not elected yet have a big influence on our lives, trust is usually crucial to their success. Monsanto has many enemies because it appears untrustworthy with its influence. But international NGOs are different, for now at least. If they fall down they are less likely to be penalised than a political party—which would lose an election—or a multinational—which would face a boycott of its products. NGO influence is thus open to abuse.

Aid NGOs carry a great responsibility because their work directly affects the world’s poorest people. They also tend to attract most public money. (Of Oxfam’s £98m budget, about 25 per cent was given by either the British government or the EU; Médecins Sans Frontières gets almost 50 per cent of its income from public sources.) They are given this responsibility because they are usually smaller and more flexible than government agencies. However, some groups are themselves now as large as a small government agency—and as bureaucratic. In many cases they have set up pervasive structures of aid provision in developing countries, taking over services such as healthcare and water supply which were previously run—however haphazardly—by the country’s government. Because these structures often collapse when the foreign NGOs leave, this approach to aid provision can end up undermining the government.

NGOs are also expensive. A report written for Unicef in 1995, by Sussex University’s Reginald Green and others, estimated that in Mozambique, health services set up by NGOs cost up to ten times as much as those provided by the government. Green recommends that foreign technical assistance should be reduced and the money used to support national or local government programmes instead. Joseph Hanlon, author of several books about aid to Mozambique, recalls that during a period in 1993 NGOs working in the health sector were spending more in two provinces than the entire national health budget—and that rather than use local doctors, they were flying in foreign experts. Hanlon calls NGOs “the new missionaries.” A provincial governor in Mozambique once told him: “NGOs are trying to take the place of the government. They are trying to show that the old colonisers are really interested in the people after all; that they can bring you water today whereas the government can only give you a well tomorrow.” Clare Short, Britain’s secretary of state for international development, warned last year that aid agencies had concentrated too much on isolated projects instead of helping governments to provide essential services such as health and education. The success of aid agencies, she said, should be measured by how soon they leave a country, not by how long they stay.

Most large NGOs, such as Oxfam, the Red Cross, Cafod and Action Aid, are striving to make their aid provision more sustainable. But some, mostly in the US, are still exporting the ideologies of their backers. “They can be either evangelical in nature, or very traditional in approach, emphasising hand-outs and soup kitchens rather than trying both to provide relief and tackle the source of the problems,” says Sarah Stewart of Christian Aid.

Yet however well intentioned, every NGO has to answer to the people who pay its bills. Accountability is central to the debate about NGOs’ role in global decision-making. Critics claim that they are hardly a democratic substitute for governments. But James Paul says that campaigning groups may be no less representative than parliaments. After all, he says, democracies are often not very democratic.

Little white lies

Environmental groups have often been accused of stretching facts to create a greater media impact. In the campaign to ban the ivory trade, environmental and animal rights groups peddled statistics on the decline of elephant populations in Africa. When Norway was targeted for killing whales, activist groups placed advertisements in national newspapers implying that all whales were threatened with extinction, when in fact the Norwegians were sustainably hunting just one species, the minke. When the Braer oil tanker went aground off Shetland in 1993 and spilled tens of thousands of tonnes of crude oil into the sea, wildlife groups predicted catastrophic effects on marine life which were never borne out. And in Greenpeace’s (ultimately successful) campaign to prevent Shell abandoning the Brent Spar oil platform in the North Sea in 1995, the group overestimated by a factor of 37 the amount of hydrocarbons in the rig which might leak into the sea. Greenpeace later apologised for its mistake over the Brent Spar, but the incident underlined how scientific facts frequently play second fiddle to politics.

The row over genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is another example. When Greenpeace activists destroyed an experimental crop of GM maize near Norwich last summer, effectively they were saying that they were rejecting GM crops irrespective of whether or not these had a detrimental effect on the environment. In this way Greenpeace can no longer strictly call itself an environmental group: it is fighting as much against global trade and the multinationals. Doug Parr, chief scientist at Greenpeace, acknowledges that the group no longer operates “wholly in the scientific domain,” but claims that public perception of the environment has moved on. “There’s a tendency among our critics to say that science is the only decision-making tool… but political and commercial interests are using science as a cover for getting their way.”

Because of their big grassroots support, environmental groups have never been limited to working through government to achieve their ends—unlike aid agencies and human rights groups. Thus the green groups are responsible for most of the innovations in NGO tactics. Now that green groups have started to campaign beyond their original remit, NGOs in other sectors may follow suit. But are any of them really ready for this shift?

Richard Jefferson, a molecular biologist and executive director of Cambia, which helps farmers in the third world, thinks not. He believes that anti-GMO campaigns in the west have already done huge damage to farming in the developing world. European institutions which have been funding the development of GM technologies for third world farmers have been cutting back because they are worried about their public image. And yet, he says, western activists are ignorant of third world farming. “They are becoming as paternalistic as the multinationals they propose to save these farmers from. If people really knew how agriculture was done here they’d thank God we had some technologies that could save us from past mistakes. If the activists really cared for the environment they would be looking at lowering pesticides usage or reducing tillage.”

Philip Burnham, a social anthropologist at University College London, who has worked for 30 years in central and west Africa, says that NGOs will often try to stifle development at any cost. He has recently been assessing the social impact of Exxon’s proposed oil pipeline through Cameroon. Exxon, he says, has been surprisingly open about the project, and local people are for it. But various US and European environmental groups are against it because they claim it will destroy rainforest biodiversity—a claim Burnham says is based on poor science. Pete Wilkinson says the problem is bigger than faulty analysis; green groups have failed to move from the confrontational tactics of the 1980s to a more conciliatory approach required today when the issues have become more complex, and business and government have adopted much of the lexicon of the movement. “After Rio, I thought there’d be a major consolidation of the green movement, a rethinking of tactics and the emergence of a more mature green lobby. We haven’t seen that.” The failure of green groups to cooperate with other “players” spurred Jens Katjek, former head of policy with Friends of the Earth Germany, to move to the corporate sector two years ago. If NGOs want the best for the environment, he says, they have to learn to compromise. Richard Jefferson is more critical still. “They’ve got everything so mixed up now. In their anti-corporatism they’ve become anti-technology, anti-science, anti-informed discussion. They do not like complexity, just the black-and-white.”

Should NGOs be granted responsibilities on the big stage if they shirk responsibilities on the small one? When they are good they are very good: a catalyst for positive social change. But when they are bad, they are self-promoting and irresponsible.

spacer

Nongovernmental Organizations and Influence on Global Public Policy

Wiley Online Library

Environmental NGOs Hurt The Poor The Most

Forbes

spacer

NGOs: Fighting Poverty, Hurting the Poor

The war against poverty is threatened by friendly fire. A swarm of media-savvy Western activists has descended upon aid agencies, staging protests to block projects that allegedly exploit the developing world. The protests serve professional agitators by keeping their pet causes in the headlines. But they do not always serve the millions of people who live without clean water or electricity.

In many of the world’s rich capitals, and especially in Washington, public policy is decided by a bewildering array of interest groups campaigning single-mindedly for narrow goals. A similar army of advocates pounds upon big international institutions like the bank, demanding they bend to particular concerns: no damage to indigenous peoples, no harm to rain forests, nothing that might threaten human rights, or Tibet, or democratic values. However noble many of the activists’ motives, and however flawed the big institutions’ record, this constant campaigning threatens to disable not just the World Bank but regional development banks and governmental aid organizations such as the U.S. Agency for International Development. If this takes place, the world may lose the potential for good that big organizations offer: to rise above the single-issue advocacy that small groups tend to pursue and to square off against humanity’s grandest problems in all their hideous complexity.

Tamil Nadu has highest number of NGOs which receive foreign funding

The Federal

Nov 8, 2022

ivakumar 10 Oct 2022 5:45 AM (Updated:8 Nov 2022 5:57 AM)

In a notice issued on July 1, the government of Sri Lanka announced that nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) would no longer be allowed to hold press conferences, conduct trainings for journalists, or issue press releases. The move has been sharply criticized by both leading activists within Sri Lanka and experienced international analysts. The U.S. State Department …

In a notice issued on July 1, the government of Sri Lanka announced that nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) would no longer be allowed to hold press conferences, conduct trainings for journalists, or issue press releases. The move has been sharply criticized by both leading activists within Sri Lanka and experienced international analysts.

Sudanese NGO registration cancelled by authorities

Sudan’s Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC) cancelled the registration of the Sudanese Consumer Protection Society on Sunday, after telecom companies had already cut off internet connection of the SCPS despite a number of official complaints.

The head of the Sudanese Consumer Protection Society (SCPS), Yasir Mirghani, told Radio Dabanga that he was officially informed on Sunday afternoon, and said he would oppose it through all legal means.

A delegation of seven Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC) officials visited the office of the SCPS in Khartoum and took the fixed and mobile assets of the Association as well as the seals, letterhead, and all documents.

Mirghani said he would appeal the decision on Monday to the HAC Commissioner-General, then to the minister, and then to the court.

Since last October’s military coup, Sudanese state ministers and officials have resorted to practices used by the former regime of dictator Omar Al Bashir, such as piling on bureaucratic procedures to extract profit and attempting to interfere in NGO procurements, according to aid workers, experts, and UN agencies.

In July, Radio Dabanga reported on violent suppression of freedoms that characterised the 30-year regime of Omar Al Bashir are increasing again in all levels of society, along with friendly ties between the military and Al Bashir’s ousted National Congress Party (NCP).

Under Al Bashir, the HAC was staffed by security officers who frequently denied access to INGOs and treated foreign aid workers as western spies.

Applications for Sudanese NGOs were often refused or given after “extra fees” were paid. HAC and security officers also regularly attended workshops and training, often in disguise. This caused the prominent NGO Sudanese Organisation for Research and Development (SORD) to temporarily register as a company instead of an organisation.

spacer

Non-governmental organizations dissolved by Ortega regime include an equestrian center and language academy

Lawmakers from the president’s party and their allies voted unanimously on Thursday to cancel 96 organizations. That followed 83 more on Tuesday. Since popular street protests turned against Ortega’s government in April 2018, the government has cancelled more than 400.

At first, the targets were often tied to prominent opposition figures who Ortega accused of working with foreign interests in an attempt to topple his government. But now the government seems intent on wiping the landscape clean of any organization it does not control.

“These cancellations have the objective of eliminating all social and political vision that differs from that established by the regime,” the Paris-based Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders said in a statement on Thursday. “It doesn’t concern only political or defense of human rights associations, but rather artistic, journalistic, educational, scientific, environmental and social organizations are also victims of persecution. The ultimate objective is to eliminate all possibility of an independent civil society in the country.”

The government maintains that the organizations are cancelled because they have not complied with a 2020 requirement to register as “foreign agents”. On Thursday, lawmaker Filiberto Núñez said they had also failed to provide financial statements as required by law.

Non-governmental organizations began to grow in Nicaragua during the Sandinista revolution and experienced a boom during the presidency of Violeta Chamorro. Incidentally, her daughter Cristiana Chamorro, a likely presidential contender now serving a prison sentence at home, decided to close the foundation named for her mother last year after the foreign agents law went into effect.

The breadth of the targets has been mind-boggling.

Thursday’s list included the Society of Pediatrics, the Nicaraguan Development Institute, the Confederation of Nicaraguan Professional Associations and the Nicaragua Internet Association.

Some are not surprising as targets, such as the Center for International Studies founded by Ortega’s stepdaughter Zoilamérica Ortega Murillo, who years ago accused Ortega of sexual abuse and now lives in exile.

But then there are organizations like the Cocibolca Equestrian Center, the western city of León’s Rotary Club and the Operation Smile Association that financed free surgeries for children with cleft lip and cleft palate until it was cancelled in March. A prominent businessman associated with that group had participated in protests in 2018.

Many organizations were dedicated to helping the most marginalized in a country already suffering from extreme economic precariousness.

Sociologist Elvira Cuadra said Ortega had sought revenge against social groups that he believes tried to remove him from office in 2018 and also seeks “to destroy the social fabric in order to eliminate the ability to oversee [the government’s] exercise of power”.

“The weaker society, the more the authoritarian state consolidates, the citizens lose the ability to demand accountability by the public administration,” she said. Now that is too funny! The NGO’s want to demand accountability of the government of the nations where they are foreign operators. But, they are not accountable or answerable to anyone. That is Rich!!

Cuadra said it was possible some of the cancelled groups were already inactive, but did not believe it was just a tidying up of civil organizations because the government was not giving them an opportunity to get in line with new legal requirements.

spacer

spacer

Amnesty Shuts Shop In India After Web Of Fraud Exposed | The Debate With Arnab Goswami

Uganda’s NGO Bureau suspends the activities of 54 NGOs in the country

Fédération internationale pour les droits humains

Sep 1, 2021 —

Restrictions to freedom of association /

Harassment

Uganda

September 1, 2021The Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, a partnership of FIDH and the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), requests your urgent intervention in the following situation in Uganda.

On August 20, 2021, the NGO Bureau, mandated under the Ministry of Internal Affairs, announced in a press release that the activities of 54 organisations in Uganda were suspended because the organisations were found to be “non-compliant with the NGO Act, 2016”.

According to the NGO Bureau, 23 NGOs were operating with expired permits, 15 NGOs failed to file annual returns and account audits, and six NGOs were operating without registering with the NGO Bureau. In all the three cases the organisations would be violating the NGO Act 2016.

spacer

Nicaragua has kicked out hundreds of NGOs

Nicaragua has kicked out hundreds of NGOs – even cracking down on Catholic groups like nuns from Mother Teresa’s order

More NGOs expelled

A series of legislative decrees passed by the National Assembly, over which Ortega wields much influence, have stripped these organizations’ rights to exist and operate in the Central American country. This status is known there as “legal personhood.”

The most far-reaching of these decrees were issued in 2022, sometimes with 100 NGOs or more losing their rights at one time. For example, decrees number 8823 through 8827, passed between July and August, removed legal recognition from 100 organizations at a time, for a total of 500.

Meanwhile, lawmakers have issued a large number of decrees in 2018 and 2019 granting recognition to domestic NGOs. The largely religious and community-based organizations may have been encouraged to carry on the operations of NGOs that were being pushed out of Nicaragua. We have been unable to learn much about how these new groups are faring so far.

Throughout 2019 and 2020, several outspoken NGOs were forced to stop operating by legislative decrees, resulting in the seizure of their assets and often the imprisonment or expulsion of their leadership. This was accompanied by legislation that included the Foreign Agents Law passed in October 2020, which mirrored word for word language used by Russia and other backsliding countries.

Nicaragua then picked up the pace of its NGO closures, including the expulsion of human rights groups and development agencies, as well as health care organizations. Even some Catholic institutions have been sent packing, with nuns from the order founded by Mother Teresa leaving the country on foot.

Nicaragua has also expelled the apostolic nuncio – who serves essentially as an ambassador of the Catholic Church – in a move the Vatican called “incomprehensible.”

spacer

The law, which goes into effect next January, requires that foreign groups find an official Chinese sponsor and register with the police. More than 7,000 such groups would have to comply, according to Chinese news reports, and their operations and finances would be subject to police examination and office searches at any time.

Recent years have witnessed what the Carnegie Endowment terms a “viral-like spread of new laws” around the world designed to limit or shut down the activities of nongovernmental organizations that promote human rights, democracy, the environment, education and other causes. China had plenty of examples of such laws to study, most notably Russia’s noxious law requiring groups that get any foreign money to register as “foreign agents,” a term that in Russia is taken to mean “spies.”

Like the other governments that have imposed such crackdowns, the Chinese government claimed its foreign organizations “management” law was an effort to protect friendly organizations while curbing political or religious activities that damage China’s “national interests” or “ethnic unity.” In the context of President Xi Jinping’s continuing efforts to tighten control over Chinese society and suppress criticism of Communist Party rule, that could mean just about anything that is not state approved or state sponsored.

Exactly how the police will wield power under this law will become known when it goes into effect. But the intent is already clear: to create a legalistic tool to intimidate foreign organizations or shut them down. Many are likely to simply quit China and cancel grants to domestic civic organizations, cutting important health, education and human rights programs. (NGO’s are not interested in helping the poor and underprivileged They are only interested in promoting the GLOBAL AGENDA)

The Obama administration was quick to criticize the law, (naturally, NGO’s are a major force in his efforts to CHANGE the World) arguing that it would reduce contacts between Americans and Chinese. Many countries will doubtlessly stay silent.

India, Egypt, Hungary and dozens of other countries have either passed or proposed similar laws in recent years to curtail the activities of nongovernmental groups. There are various reasons for the rise in these laws, experts say, including resentment of Western ideas and influence among developing and post-Communist countries, since many major international groups are based in Western democracies, and a fear among less-than-democratic regimes of the power of independent organizations to fuel opposition to their rule.

The nations who have been leading the fight against NGO’s are the very nations they claim to exist to help! Don’t you find that revealing?? These people have given them long enough to have discovered their true purpose. NGO’s undermine local and NATION Sovereignty. They work to enforce the Globalist Agenda. We here in the USA should wise up and follow their lead. PUT N END TO NGO’s and all the others who are working to undermine our Nation Sovereignty and destroy our rights to self governance.

Elliot C. Williams

Elliot C. Williams