Update: Video added 10/27/22

For I would not, brethren, that ye should be ignorant of this mystery, lest ye should be wise in your own conceits; that blindness in part is happened to Israel, until the fulness of the Gentiles be come in.

There is a phenomenon that is happening is Israel. Though the Jews say they are declaring him the Messiah, their is much evidence that their is a movement in that direction. They have already crowned his a Yanuka. That probably doesn’t mean much to most of us here in America who have no understanding of the meaning of the word Yanuka. Once you have finished this post, you will have a much better idea.

This man is a staunch student and preacher of Rabbinical Judaism, based on the the Midrash the Talmud and Kabbalah, as well as the Torah. He is exalted for his spiritual teachings and insights. Though most of them would not be the least bit biblical in the eyes of bible believing followers of Christ.

I am not as much interested in this Yanukah as I am in the people of Israel as a whole and their obvious hunger for the Spiritual Things Of GOD! They flock to hear this man. They seek him out for miracles.

This, I believe is a sign not only that we are in the end times and the AntiChrist is about to be revealed, but that the time of the Gentiles HAS ENDED!! God is returning His focus onto the Jews/Hebrews.

This man is NOT the Messiah, he is very likely could be the AntiChrist. Regardless, I think God is using him to stir the hearts of the Hebrews/Jews.

We cannot trust anything we see. The elite study the Word of God and the Signs in the Heavens. They have access to historical documents that we have never laid eyes on. Always bear in mind that the times we are living are the times of GREAT DECEPTION. Deception is their most powerful weapon. They study and they KNOW what is coming and they SEEK to control it, stop it, cover it up or pervert it. So be wise as serpents and gentle as doves.

We KNOW that GOD is always in control. By the signs that we see we should KNOW that we are at the end and it won’t be long now before the Heaven’s Split to reveal the TRUE MESSIAH!!

spacer

If you have not seen my original post on this topic, you can view it here:

spacer

THE JEWISH FALSE MESSIAH HAS BEEN CROWNED

also see:

NEW RELATED POST ON YANUKA : What will come of all of this?

spacer

1Then spake Jesus to the multitude, and to his disciples, 2Saying, The scribes and the Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat: 3All therefore whatsoever they bid you observe, that observe and do; but do not ye after their works: for they say, and do not. 4For they bind heavy burdens and grievous to be borne, and lay them on men’s shoulders; but they themselves will not move them with one of their fingers. 5But all their works they do for to be seen of men: they make broad their phylacteries, and enlarge the borders of their garments, 6And love the uppermost rooms at feasts, and the chief seats in the synagogues, 7And greetings in the markets, and to be called of men, Rabbi, Rabbi. 8But be not ye called Rabbi: for one is your Master, even Christ; and all ye are brethren. 9And call no man your father upon the earth: for one is your Father, which is in heaven. 10Neither be ye called masters: for one is your Master, even Christ. 11 But he that is greatest among you shall be your servant. 12And whosoever shall exalt himself shall be abased; and he that shall humble himself shall be exalted.

13But woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye shut up the kingdom of heaven against men: for ye neither go in yourselves, neither suffer ye them that are entering to go in. 14Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye devour widows’ houses, and for a pretence make long prayer: therefore ye shall receive the greater damnation.

15Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites!for ye compass sea and land to make one proselyte, and when he is made, ye make him twofold more the child of hell than yourselves. Matthew 23

spacer

spacer

spacer

spacer

Here is a link to the Yanuka youtube page.

Jesus had a lot to say about the Scribes and Pharisees, the Religious leaders of his day. None of it was very complimentary. He called them out for the arrogant manipulators and false teachers that they were. I love this particular response he gave them.

Woe unto you, Pharisees! for ye love the uppermost seats in the synagogues, and greetings in the markets. Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye are as graves which appear not, and the men that walk over them are not aware of them. Luke 11:43&44

The “learned men” love Titles and Honors. They love to lord it over the people. They love to control people by intimidation. Making the masses believe that they are below them, because they are “wise”.

But, GOD is no respecter of persons, and those titles mean nothing to God.

In Leviticus Moses reminds the children of Israel

You shall do no injustice in judgment. You shall not be partial to the poor, nor honor the person of the mighty. In righteousness you shall judge your neighbor. Leviticus 19:15 NKJV

Leisa Baysinger

Much confusion has occurred over these words… So, where does the confusion come from and what do these different words actually mean in their correct historical context?

First of all, these words have changed in meaning from pre-temple to post-temple times. What these words meant prior to the destruction of the temple in 70 AD is not what they meant after the destruction of the temple…

The word Rabbi (pronounced Rahb -bee) comes from the Hebrew word rav (rab), which in Biblical Hebrew meant “great.” The word Rabbi therefore means “my master” or “my great one”. This word was also used as a term of respect that was used by slaves when they were addressing their owners and it was sometimes used to refer to high government officials or army officers.In Yiddish the word is Rebbe. The title Rabbi was used primarily in Israel. In Babylon the term Rav was used instead of Rabbi.

The term Rabban was used to refer to the Rabbi who was over the Sanhedrin.According to Jewish sources, it was first used as a title for Rabban Gamaliel the Elder, who was over the Sanhedrin at the time of Jesus (Yeshua) and Paul. Gamaliel was the son of Hillel The Elder. After this it was used to refer to Rabban Simeon his son, and Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai. Everyone needs to study Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai as he was the Rabban that survived the destruction of the temple and was smuggled out in a coffin, by his disciples, and would go on to start a study center in Yavneh. It is from this that modern Rabbinic Judaism emerged.No one was called Rabban unless they were presidents over the Sanhedrin.

Rabboni means “my great Rabbi”. According to Jewish sources, Rabbi is greater than Rav; and Rabban is greater than Rabbi.The use of these words did not take place prior to the first century. For example, according to Jewish literature, Hillel The Elder was considered one of the greatest Rabbi’s of all time, but he bore no title of respect. Hillel The Elder was from the lineage of David and flourished around 20 BC until about 10 AD. Yeshua had many teachings similar to those of Hillel.

It was only after the destruction of the temple that the term Rabbi became a FORMAL TITLE for a teacher of Torah. This title is used today in Judaism. To be a Rabbi one has to have the formal ordination and laying on of hands. The term could not technically be applied to Yeshua as a learned teacher in His day but He would more appropriately have been called a sage. Again,the title Rabbi during Yeshua’s day meant “great one” and was used as above; to refer to those highly regarded and respected,it did not mean teacher during that time period. So, Yeshua was a sage, a teacher, but He was also called by the term Rabbi which was a word showing great respect and high honor. Sages were considered teachers.

What a crazy bunch of double talk.

spacer

spacer

The Difference Between a Rabbi and a Rav

Answer:

First, to clarify some terms. In common parlance, “rabbi” is the catch-all term for anyone who has semichah, rabbinical ordination (read more about that here). “Rav” on the other hand, has come to refer to someone who has had more extensive training and experience in providing guidance related to practical halachah (Jewish law). A rav also gets appointed by a community to answer halachic questions…

Rabbi vs. Rav

The reason that sometimes only a rav can answer your question is because there are two types of questions. There are questions that are clear. They are dealt with in books of Jewish law, and all we need to do is find the answer and relay the information. In that arena, anyone who knows the answer is qualified.

Then there are questions that are not found inside the books. These are the questions that are not black and white. To answer that type of question requires comparing cases and making inferences. Sometimes there are multiple opinions about what Jewish law says, and the rav’s job is to evaluate which opinion to follow. That is something that only a rav, who was given that power and responsibility by a community, can do.

Three things a rav needs: Expertise, Experience & Authority. Authority requires a significant community.So to sum it all up, why can’t the Ask the Rabbi people be good enough all the time? Because they aren’t qualified to make certain decisions. They might have knowledge and experience, but only a rav has the authority to make certain rulings. On top of that, they don’t really know who you are, and so cannot give you custom-tailored answers. You can still ask them questions, but sometimes, they will send you up the chain to a rav.

All of that was a surface-level answer. If you are satisfied with that, great—you can stop here. But for those who want to dig some more, there is actually a much deeper reason why certain issues can be dealt with only by a qualified rav.

Why Rabbis Are Not Like Doctors

This is because a rav is actually not like a doctor at all.

We go to primary care physicians as opposed to random doctors or nurses because they have a smaller chance of being wrong about how to treat us. Their experience and personal knowledge of our situation makes it less likely that they will misdiagnose us. So a doctor is all about damage control.

The value in a rav is not in the better chances of a correct diagnosis. The value in a rav is that going to him is the healing in and of itself. G‑d set up a system.1 That system is that when we have a question, we are to go to a rav and listen to what he says. So we are not going to the rav for information; we are going to the rav because G‑d said to go to a rav.

When a rav tells you something, it is not an opinion. It isn’t take-it-or-leave-it advice. He is telling you what G‑d wants you to do, because G‑d said to listen to your rav. When it comes to halachah, there is no going to another doctor for a second opinion. The opinion you get from your rav is final and indisputable.

It gets even deeper than that.

Since asking a rave is part of G‑d’s system, He upholds whatever decision the rav makes… We trust that as long as the rav follows the guidelines of the Torah, his decision is backed by G‑d.

What he says is the answer that is right for your soul.

It gets even deeper. Kind of.

But first, a story. (Who doesn’t love a good story?)

This is a story of the Baal Shem Tov.

One day a man came in to him with a very serious question. He had just been to a Jewish court for a monetary dispute. After reviewing the case, the presiding rav ruled that he was obligated to pay. He had lost the court case.

He told the Baal Shem Tov that he was not upset with the ruling, he was just confused. He knew in his heart that he did not owe the money. The claims against him were false. But he also knew that the rav had followed all the laws of the Torah and had justly ruled against him. How could the Torah of truth support a ruling that was itself untrue and unjust?

The Baal Shem Tov listened to his question, stroked his beard for a minute, and told him the answer.

“Your soul,” the Baal Shem Tov related, “actually owed money to the soul of that other man in a previous lifetime. Unfortunately, you passed away without ever being able to repay your debt. It was therefore decreed that in this lifetime, in your time back on earth, you would be obligated by the Torah to pay him back the money you owe. But you could not have owed the money to him in this life, for then it would not count for your previous life. It is only because you truly do not owe him anything that the money you gave him can repay the debt of your previous incarnation.”

Pretty crazy, huh?

So, the ruling of a rav that is based on the methods of Torah is not only a just decision in this life, but it is justice that transcends the limitations of just one body or plane.

WOW… So, Rabbinical Jews and/or those who practice KABBALAH believe in reincarnation. Totally Unbiblical. If you want to know more about their beliefs on that topic check out this site:

6 Things Jews Believe about Reincarnation

spacer

The full article can be read on the website, what shown below are merely excerpts of the basic tenants presented in the article.

a man of self-sacrifice, Torah genius, lofty character, prophetic ability, miracle-worker, etc., etc.

he is a nassi – A nassi, broadly defined, is a “head of the multitudes of Israel.”3 He is their “head” and “mind,” their source of life and vitality. Through their attachment to him, they are bound and united with their source on high.

There are several types of nesi’im: those who supply their constituents with “internalized” nurture,4 and those whose nurture is of a more “encompassing” nature.5 This is further divisible into the particulars of whether they impart the teaching of the “revealed” part of Torah, its mystical secrets, or both; whether they offer guidance in the service of G‑d and the ways of Chassidism; whether they draw down material provision; and so on.

There are also nesi’im who are channels in several of these areas, or even in all of them.

they nurture their chassidim in both the “internal” and the “encompassing” qualities of their souls; in Torah, divine service and good deeds; in spirit and in body. bond with those connected with them is in all 613 limbs and organs of their souls and bodies.

he is the source and channel for all our material and spiritual needs, and that it is through our bond with him that we are bound and united with our source, and the source of our source, up to our ultimate source

spacer

The following article is lengthy but it is worth perusing because it gives you insight into how and why Jews exalt young boys as Yanuka/Wonder Boys.

YANUKA: Boy Wonders – סגולה

This article was published in issue 56 | Adar 5781 | March 2021

This article was published in issue 56 | Adar 5781 | March 2021

In the summer of 1873, Rabbi Asher Perlov, master of the Karlin Hasidic dynasty (originating in Karlin, near Pinsk, in today’s Belarus), passed away in nearby Stolin. Only forty-six, Rabbi Asher left behind a daughter from his first marriage and a long-awaited son from his third. His followers hurriedly crowned the son, Yisrael, as their leader, though he wasn’t yet five years old.

Rabbi Yisrael of Stolin may have been the youngest Hasidic leader ever appointed, but he was by no means the only such boy rebbe, or even the first. Hasidim call a child who succeeds his father a yanuka, from the Aramaic word meaning a nursing infant. The few such cases were both famous and controversial, teaching us a great deal about Hasidic courts and their leadership.

Dynasties are one of the phenomena most closely identified with Hasidic groups. (in the 19th century, it is estimated that roughly half of Eastern European Jews were Hasidic) Lineage has always been an important element of Jewish spiritual leadership. The presidency of the Sanhedrin traditionally passed from father to son, and many of eastern Europe’s early modern rabbinic dynasties traced themselves all the way back to the House of David. In contrast, the Baal Shem Tov came from no distinguished family and passed his mantle on to his disciples – Rabbi Yaakov Yosef of Polnoye; Rabbi Dov Ber, the Maggid of Mezritsh; and Rabbi Pinhas Shapira of Korets. Yet from the 1780s, Hasidic leadership became increasingly hereditary.

Outside of Hasidism, rabbinic dynasties were seen as preserving a family’s scholarship and prestige. For Hasidim, however, their sainted leaders were a vital link in a chain of succession orchestrated by God Himself. Inherently holy, they bore a divine spark transmitted from father to son through the generations.

Outside of Hasidism, rabbinic dynasties were seen as preserving a family’s scholarship and prestige. For Hasidim, however, their sainted leaders were a vital link in a chain of succession orchestrated by God Himself. Inherently holy, they bore a divine spark transmitted from father to son through the generations.

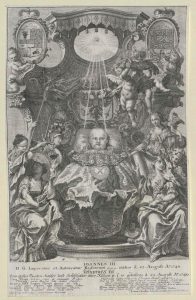

The hereditary nature of Hasidic leadership suggested a kind of royalty or aristocracy. Indeed, Louis XIV was crowned king of France when he was around five, more or less the same age as the Yanuka of Stolin took his father’s place. The Hasidic tendency to treat rebbes as royalty was seen by the movement’s opponents as proof of its deeply ingrained moral rot. Dynastic leadership, in their eyes, only increased the gap between classes in Jewish  society while justifying an authoritarian hierarchy.

society while justifying an authoritarian hierarchy.

Child’s Play

Though crowning a yanuka to replace his father as grand master was perfectly logical from a dynastic point of view, could a boy do the job? Rabbi Barukh Mandelboim of Turov – a central figure in the Karlin Hasidic court – assured his followers that young Rabbi Yisrael of Stolin’s spiritual stature was far beyond his years:

Turn your steps and your hearts, and let your feet take you joyfully up to the abode of joy […], and journey to Stolin in time for the holiday of holy law-giving […]. For did not the master, his saintly grandfather, […] say in these very words, “The child’s hands grant protection”? In him you’ll find protection from the counsel of the evil inclination […], and all will be sweet and well with you, and you’ll be well-endowed both spiritually and physically. (Yehuda Leib Levin, “Discovery of the Yanuka in Stolin,” Ha-shahar, Tishrei 5635 [1874], p. 40 [Hebrew])

(Left)Jews in the town square of Stolin, home to the youngest known yanuka, 1929 YIVO Archives

Mandelboim wrote that the mere touch of the young rebbe’s hands worked like a charm – and that belief in his powers was more important than hearing his words. The rabbi reported that the Yanuka’s mother had appointed guardians to groom him for his role and support him until he reached adulthood. Meanwhile, they’d undertake some of his responsibilities. And Rabbi Barukh pointed out that the biblical King Jehoash was also crowned young – at age seven – under the guidance of the high priest Yehoyada.

Mandelboim’s effusive letter implies that the child’s position was far from secure. Perhaps the Hasidim feared that a boy could hardly provide the requisite leadership: addressing the burning issues of the time, inspiring with his words of Torah wisdom, performing miracles, representing his community before God, and offering personal counsel. Surely some avoided the yanuka’s court rather than consult a five-year-old regarding their business, family, or health problems.

One Hasid recalled his grandfather’s experience with Rabbi Yisrael:

My grandfather, Reb Pinhas Yosef Shapira (may he rest in peace), would go up to Stolin for the festivals of Shavuot and Hanukka and as the need arose, which it did fairly frequently: when he had to pay his yearly leasing fee but had no money, or when one of his sons received a summons from the army […]. And when it was time for the Hasid to return home, he’d go to Reb Yisrael Binyamin (the gabbai [court secretary]) and hand him a note for the rebbe, with the appropriate donation, and together they proceeded down the long corridors, looking for the rebbe in order to get a farewell blessing. When they found him, busy with his toys, the gabbai would address him with all due respect:

“Rebbe, Pinhas would like to go home to Gritsev, and he’s here for a farewell blessing.”

“Let him go in peace. What’s keeping him? Go in peace, Pinhas.”

Reb Pinhas approached the Yanuka and said: “Rebbe, my son David Aharon has been called for military physicals and asks your blessing to [help him be] released [from army service].”

“May it be as you say, Pinhas. May he be released.”

“Rebbe, my income could be better.”

“Better, better, may it improve. Goodbye, Pinhas.”

Leaving them standing there, he turned back to his games.

The gabbai solemnly repeated the Yanuka’s words: “Go in peace, Reb Pinhas. May God, blessed be He, help you, and may your son be released and your income improve, God willing, in the merit of the righteous.”

As the yanuka played, the Hasid would shake Reb Yisrael Binyamin’s hand and go home to his family full of hope and encouragement. (Stolin – A History of the Stolin Community and Its Environs, ed. Arye Avatichi and Yohanan Ben-Zakkai [Tel Aviv: Association of Stolin Emigrants in Israel, 1952], p. 154 [Hebrew])

The slight ambivalence reflected above contrasts sharply with a description of the same Yanuka of Stolin by Avraham Abish Shor in a Hasidic periodical:

Wonderful were his ways, modest and retiring in the extreme. As he played with other children his age […], he’d reveal great matters as if by chance through his apparently childish actions. […] They’d seat the yanuka at the head of the table, and he’d slip away and hide underneath […] and say, “How can I sit at the head of the table where God’s holy name stands before me, making my eyes ache?” (Avraham Abish Shor, “On the Golden Dynasty and the Holy Soul of Our Teacher, the Or Yisrael of Stolin, May His Merit Protect Us, Amen,” in Beit Aharon and Yisrael Almanac, vol. 6, pt. 4 [1991], p. 162 [Hebrew])

Yet even when a yanuka was somewhat older, his age made some uncomfortable. The grandson of Rabbi Hanokh Krupnik, a disciple of the Talne Rebbe of Sharhorod, Ukraine, wrote of his grandfather:

Since his youth, he’d followed Rabbi David of Talne. When Rabbi David died and his grandson, who’d just become bar mitzva, was appointed in his place, [my grandfather] retorted [in Yiddish]: “I’m not going to any youngster!” and ended his allegiance to Talne Hasidism. (Barukh Karu [Krupnik], “Three Towns,” in He-avar [The Past] – A Quarterly on the History of Jews and Judaism in Russia 20 [Elul 1973], p. 264 [Hebrew])

The rabbi’s indignation was by no means his alone. It expressed an ongoing tension between traditional Jewish leadership – essentially a meritocracy based on rabbinic learning – and the Hasidic version, based on hereditary sainthood.

Kingship is dangerous for children, whose very existence blocks other claimants from the throne. Ivan VI of Russia was crowned at two months old, deposed a year later, imprisoned, and killed in the last of many attempts to free him before he turned twenty-four. Engraving of his coronation in 1740, emphasizing the divine election of royalty.

Kingship is dangerous for children, whose very existence blocks other claimants from the throne. Ivan VI of Russia was crowned at two months old, deposed a year later, imprisoned, and killed in the last of many attempts to free him before he turned twenty-four. Engraving of his coronation in 1740, emphasizing the divine election of royalty.Order in the Court

Some Hasidim actively opposed the appointment of a yanuka. In 1881, Rabbi Yeshaya Meshulam Zishe Twersky of Chernobyl died, leaving only one son – Shlomo Benzion. age eleven. Though the Chernobyl Hasidim appointed the boy to succeed his father, an anti-yanuka faction rallied around Shlomo Benzion’s uncle, Rabbi Barukh Asher of Chernobyl. This group wrote to Rabbi Avraham Twersky, the Hasidic master of Trisk (Turiisk, in today’s Ukraine), declaring the yanuka’s coronation idolatrous and asking the rabbi to support Rabbi Barukh Asher:

Empty, simple people got together, rough, uncouth laborers and artisans who can’t tell right from left. They gathered to profane the name of Heaven in public, setting up a stage and seating his young son on the rabbinic throne, though this tender young boy hadn’t yet read [from the Torah] or taught in his life.

His precious soul, hewn from the holy quarry, was lost among the fools who confused his power and his body and gave him donations and led him to the holy tomb, where they pronounced him rebbe and then and there began seeking his counsel, though he didn’t know what they were talking about. “They say to [a piece of] wood, ‘You are my father” (Jeremiah 2:27).

They don’t let the boy study God’s law, which could guide him on God’s path so that he might gradually follow in the footsteps of his holy forefathers, and thus might his deeds eventually approach his fathers’. Instead they confuse him and don’t leave him [in peace] to grow up until his beard fills in. They’re literally destroying a precious soul, Heaven forfend.

Even with our limited vision, we can see and understand the great sorrow that now pains his holy ancestors in Paradise. They’re troubled by the loss of this precious pearl, and even more so by the desecration of God’s name and the resulting weakening of belief in Him and in His servants in this generation. All their lives, they devoted themselves to sanctifying God’s name and instilling His faith in the hearts of Israel, that the common folk might seek out mouths of wisdom for sage and faithful counsel. Yet today our eyes see instead how a tender, ignorant lad is made a leader, and our hold on faith may slip for lack of stave and support, God forbid. (National Library of Israel, manuscript ARC 4° 1699, 10/b [Hebrew])

Expressing concern for the healthy development of their prematurely burdened leader, the writers also hint that he’s incapable of fulfilling his duties. He can’t answer his followers’ questions, and they take him and their kvitlekh – notes asking him to intercede with Heaven on their behalf – to his father’s grave. Though fledgling Hasidic masters do customarily visit their ancestors’ tombs for guidance, here the practice is presented as proof that the Yanuka of Chernobyl isn’t up to the job.

A further objection to the succession of a yanuka was the fact that he had the natural support of the personalities who’d run his predecessor’s court; the election of an easily dominated child protected their positions. His mother, too, automatically became a highly influential figure in his court. After Menahem Nahum of Talne succeeded his grandfather, a correspondent to Ha-melitz (The Advocate) lamented:

: Since the saintly Rabbi Duvid’l passed away, peace has passed away from our town. He guided the flock in his wisdom, and no one plotted to disturb the peace, even if some secretly grumbled [against him] in their tents. He knew how to navigate the ways of the community with tolerance, so quarrels wouldn’t break out, […] but today our congregation is like most other congregations of Jacob in our land: there’s no end to the fighting […].

And all because of the holy child who sits on his grandfather’s throne with the help of the deputy, Reb Yaakov, the departed rebbe’s sister’s son. For since the boy is young, we’re ruled by a woman, namely his mother. The working-class commoners sanctify the holy child in his diapers and idolize him, ready to flay like a fish any who refuse to listen with all ears to every syllable uttered by the hereditary saint. (“Everyday Stories: In Our Land,” Ha-melitz, 17 Sivan 5643/June 22 1883, p. 698 [Hebrew])

His accession as a yanuka sent some of his grandfather’s followers scurrying to other Hasidic courts. Rabbi Menahem Nahum Twersky of Chernobyl and the town’s synagogue circa 1900

All in the Family

With all these problems, why did Hasidim continue appointing children, despite the resultant drop in popularity at their courts? One answer is court politics. Not infrequently, the instatement of a youngster was intended to thwart the succession of a rival family member. The hasty appointment of the Yanuka of Stolin, for instance, was designed to stop his mother from installing her thirteen-year-old son from a previous marriage instead. Using one yanuka to block another was simply an insider faction’s way of preventing a family of outsiders from taking control.

There was also a financial incentive. All the economic activity generated by a Hasidic master – donations, payment accompanying requests for blessings and personal advice – would be lost to his family, particularly his widowed mother, who had no income after her husband’s early demise.

Widows of Hasidic masters could be left destitute, prompting them to promote the succession of their sons, however young. Isidor Kaufmann, Friday Evening, circa 1920. Courtesy of the Jewish Museum, New York

Widows of Hasidic masters could be left destitute, prompting them to promote the succession of their sons, however young. Isidor Kaufmann, Friday Evening, circa 1920. Courtesy of the Jewish Museum, New YorkFinally, as stated, Hasidim believed that the yanuka’s soul had God-given powers. The families of these children regularly described them as prodigies well before circumstances thrust them into the limelight. In Stolin, for example, Rabbi Asher Perlov had waited many long years for a male heir, and in the intense rejoicing surrounding his birth, the child was crowned with many grand titles and expectations. Similarly, Rabbi David Twersky, Hasidic master of Talne, whose only son died young, touted his grandson’s outstanding character long before the boy was due to succeed him.

Head Table

Dr. Samuel Aba Horodezky was descended from the Hasidic master Rabbi Menahem Nahum of Chernobyl, but embraced the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah). Nonetheless, his description of the Yanuka of Chernobyl’s coronation at his bar mitzva in 1883 is telling. Horodezky himself was only twelve at the time, but the experience left a profound impression:

Hundreds of Hasidim gathered from near and far to see the wonderful sight. For on that day he became a great Tsaddik (saintly leader), and from now on he would accept kvitlekh, dispense blessings, amulets, and [other] protective charms, and hold court at the head of the table (tish) on the Sabbath, singing Sabbath melodies. (Samuel Aba Horodezky, Memoirs [Dvir, 1957], p. 19 [Hebrew])

Hasidic courts became institutions in their own right, requiring a donation for every kvittl (written request) handed to their saintly leaders. Moshe Maimon, Visiting the Rebbe, St. Petersburg, 1899. Jewish Historical Institute Collection, Warsaw

Members of the rebbe’s entourage were stationed outside his residence to write Hebrew kvitlekh for those who couldn’t. National Digital Archive, Warsaw

Members of the rebbe’s entourage were stationed outside his residence to write Hebrew kvitlekh for those who couldn’t. National Digital Archive, WarsawThe first Sabbath on which the yanuka presided also gets a mention:

There was utter silence in the hall. These Hasidim, most of whom had been lucky enough to sit at the elder tsaddik’s table, saw and felt again what they’d seen and felt then. There was no difference between the old, deceased tsaddik and the young, living one. All those gathered there looked only at him, never shifting their gaze from his movements and signals. He sat like one long accustomed, confident and loyal. (ibid., p. 20)

During the Sabbath singing, the yanuka surprised them with a new melody, then distributed the remnants of his meal (shirayim), as was customary. His audience marveled:

Great rejoicing broke out, seizing all the Hasidim. Affection and brotherhood overcame them, rich and poor alike, learned and ignorant, and they all stepped forward as one to dance and sing: “For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given; and the government will be upon his shoulder” (Isaiah 9:5). Finally he too appeared and joined their dance. They said: At that moment, all merited a glimpse of the Shekhina [God’s presence]. (ibid.)

The verse from Isaiah has been interpreted by both Jews and Christians as a reference to the Messiah, who will continue the Davidic dynasty. As far as the Chernobyl Hasidim were concerned, the yanuka was also a redeemer, saving his dynasty from extinction.

Horodezky, who had no children, was particularly moved by youngsters and attributed special powers to some. In 1929, decades after the yanuka was crowned, Horodezky published an article in the first issue of the literary periodical Moznayim (Scales). “Yanuka (Mysterious Types)” was a brief summary of wonder children in Jewish tradition, from the Bible to the Hasidic dynasties. Along the way, Horodezky discussed the yanuka appearing in the Zohar, the child who amazes the sages with his insights – and inspired the title given to young boys appointed as Hasidic masters.

When Grand Rabbi Aharon Rokeach of Belz died in 1957, his nine-year-old nephew Yissachar Dov succeeded him but began fulfilling his duties only at age eighteen. Rabbi Yissachar Dov Rokeach, the present Belzer rebbe

When Grand Rabbi Aharon Rokeach of Belz died in 1957, his nine-year-old nephew Yissachar Dov succeeded him but began fulfilling his duties only at age eighteen. Rabbi Yissachar Dov Rokeach, the present Belzer rebbeThe Wonder of Childhood

Certain cultures view children and childhood symbolically. Jung emphasized the importance of the child in both civilization and religion. In many myths, the Swiss psychiatrist pointed out, the child represents innocence, simplicity, and purity, the primordial unity and harmony that preceded all discord and distinction. The child is not yet constrained by social norms or tainted by sexual desire.

Yet childhood is also associated with old age – the two outliers of human life – as the child carries the burden of the past into the future. Children are therefore often credited with wisdom beyond their years, which even adults have yet to achieve. Still whole and at peace with themselves, they’re considered a gift from God, connecting heaven and earth. This last aspect was often exactly how Hasidic masters were perceived. Hence the notion that a mere child could replace a saintly Hasidic leader.

Yet childhood is also associated with old age – the two outliers of human life – as the child carries the burden of the past into the future. Children are therefore often credited with wisdom beyond their years, which even adults have yet to achieve. Still whole and at peace with themselves, they’re considered a gift from God, connecting heaven and earth. This last aspect was often exactly how Hasidic masters were perceived. Hence the notion that a mere child could replace a saintly Hasidic leader.

Hasidism chose its leaders not so much for their erudition as for the holiness inherited from their fathers. Though a Hasidic master might be both learned and righteous, most important was his continuation of those who preceded him. For his Hasidim, the yanuka personified the pure holiness of the dynasty, and they hoped and believed that with time, that sanctity would trickle down to them too.

(Right) The innocence of youth bears an aura of sanctity. Isidor Kaufmann, Portrait of a Boy, 1895. Courtesy of the Jewish Museum, New York

spacer

A prophetic allegory first told 170 years ago has resurfaced, related by one of the most respected rabbis in Israel who heard it many years ago when he was a boy sitting with his father. The rabbi explains that the story, first told by a wonder-working Hassidic leader, foretold a conflict between Russia and the US, but in the end, China would emerge victoriously.

A video was recently posted to the internet in which Rabbi Yitzchak Dovid Grossman, the scion of one of the most respected Hassidic families in Jerusalem, related a story from his childhood in which a prophecy was discussed by his father and another rabbi concerning the outcome of the current crisis in Ukraine.

Rabbi Grossman begins by describing how he used to sit by his father, Rabbi Yisrael Grossman, the head of the Agudath Yisrael rabbinic court, and learn Torah in the synagogue.

“When they wanted to honor someone in the synagogue, they would allow them to sit next to my father,” Rabbi Grossman related. “One day, a man sat down next to my father. My father treated him with great respect but I didn’t know who it was because I was very young at the time. He began to tell my father a story that he listened to with great interest. It seemed so exceptional that I remember it to this day.”

“The man related what he heard when he was with the ‘Yanuka’ in Stolin (Belarus) many years earlier,” Rabbi Grossman said. The ‘Yanuka’ was Rabbi Yisrael of Stolin. He was the son of Rabbi Asher, the spiritual leader of the Stolin branch of Hassidic Judaism. The Yanuka was born in 1869 and his father passed away when he was just four and a half years old. His piety and Torah knowledge were already so remarkable that at that young age, he was appointed as the sect’s spiritual leader in his father’s place, until he passed away in 1922.

Rabbi Grossman related how the Yanuka once gathered his followers together for a special message.

“The Yanuka told his followers what would be before the arrival of the Messiah,” Rabbi Grossman related. “Two roosters will be fighting terribly, trying to kill each other, when along will come a third rooster who will finish them both off.”

The story finished with an incongruous ending.

“But Israel, thanks to their great belief in God, will be spared from danger,” Rabbi Grossman said.

Rabbi Grossman’s father was confused after he heard the story.

“What are you talking about?” his father asked at the time. “What is all this talk about roosters?”

The mysterious stranger answered in the name of the Yanuka, who passed away more than two decades before Rabbi Grossman was born. “The two roosters are Russia and America. Who is the third rooster that will finish off both the US and Russia? That will be China,” the Yanuka said more than 170 years ago.

“At the time, China was like a kindergarten,” Rabbi Grossman said. “They were a huge country but backward in culture and technology and had a military that had no real weapons. Who could have imagined that China would one day be the biggest threat in the world?”

“The vision of righteous men is almost like prophecy and can foresee things regular men cannot,” Rabbi Grossman said. “God should protect us from what the Chinese leaders have in mind. We are already beginning to see all that was prophesied to be before the Messiah. We are currently in the final stages of the Moshiach (Messiah).”

“The only solution at this stage is to increase in prayer and belief in God, to engage in charity, and to do God’s will,” Rabbi Grossman said. “We are about to see that God is One and His name is One.”

Rabbi Grossman is the sixth generation of his family residing in Jerusalem. He is universally respected and has been offered the position of Chief Rabbi of Israel twice, but declined both times in favor of continuing his outreach work.

spacerpacer

PERFECT HARMONY

MAY 26, 2020

We’re outside, waiting for the Yanuka.

It’s silent in the deserted courtyard of the little shul, for even though coronavirus restrictions have been eased and the streets have again come to life, most people are in bed at this hour. But we’re waiting — and then we see him. Soon we’re face to face with this bashful young man who’s taken the Torah world by storm — self-effacing, unremarkable in appearance, but so remarkable in the impact he’s had on the lives of the thousands who flock to him, hanging on his every word.

He’s really just a young avreich, yet his shiurim are an attraction for the masses, from all ages and stages: elderly chassidim and litvish talmidei chachamim and everything in between. When he sits on the dais of packed halls, expounding on all parts of Torah by heart, the brim of his hat is just about covering his eyes, and at the same time that he’s electrifying the crowd with his depth and breadth, he seems to be melting into himself, erasing his very yeishus. After all, he’s just a vessel, a kli — it’s not about him at all. And then, when the shiur is over, the spellbound audience already knows what to expect: A Roland keyboard is brought out and this shy genius — the Yanuka, as he’s been known since his teenage years (a reference in the Zohar to souls who already from childhood are exceptional in their Torah knowledge) — will begin to play a medley of stirring songs sure to awaken slumbering souls.

His name is Rav Shlomo Yehudah Beeri (to most people, he’s simply known as Rav Shlomo Yehudah), and although he’s not really a yanuka anymore — he’s 32 years old — he’s still decades younger than many of his followers. Aside from the fact that he commands such respect despite his young age, his popularity has skyrocketed even though he doesn’t peddle yeshuos, kameios, or mystical deals. His merchandise is pure Torah — all of it, on the tip of his tongue.

The shul where we meet has just been reopened for the public, but even during weeks of closure, the ezras nashim was still his private learning space. This is like his second home, and as he invites us in and flicks on a small light, we take our seats in the shadows.

“There are times when we need to serve HaKadosh Baruch Hu with mochin dekatnus (a state of constricted consciousness),” Rav Shlomo Yehudah says, explaining to himself as much as to us why the shul has been empty, bereft of its beloved worshippers. “Sometimes this is decreed on a person, on a family, a city, village, and sometimes it is an entire generation. In our generation, it has apparently been decreed that people must pay attention to the tachlis, to the main point. To stop everything and reflect. It’s like HaKadosh Baruch Hu is telling the world, ‘Enough,’ after people started to think that everything is permitted. They had their money, were confident in their way of life. When you live like that, you might consider yourself a ma’amin, but how much do you really unconditionally trust in Hashem?”

The problem in our day, says Rav Shlomo Yehudah, is that when we daven, it’s not out of desperation, it’s not with a sense of absolute dependence on HaKadosh Baruch Hu. “Once, a person would go out to the market and ask Hashem to send him parnassah or to bring rain to water his field or to bring fish to come to where he’s fishing. Today people have emunah because it says you’re supposed to have emunah, but they don’t really live it on an experiential level in their lives.”

The Rav doesn’t sound upset or bitter though — he’s just stating a point, going with the flow of things as they’ve been decreed to be. In fact, that’s how he’s always lived his life, from the time he was a poverty-stricken child moving from place to place through Eretz Yisrael, Europe, and back with his parents. “People think they know Who HaKadosh Baruch Hu is and what Torah is, and then, Hashem suddenly does something that no one can process, shaking up the order of Creation,” Rav Shlomo Yehudah explains. “Once we understand that we have no grasp of the Creator and really begin to serve Him with temimus and with awe, no longer being so sure we have all the answers and instead looking with respect at everyone simply because they have a tzelem Elokim, then perhaps the this pandemic will be annulled, b’ezras Hashem.”

He believes that the violation of the tzelem Elokim — through lashon hara and sinas chinam — is even hinted to in the current lockdown rules. “The isolation period for those who’ve come in contact with coronavirus is 14 days, like the isolation for the metzorah who speaks lashon hara,” the Yanuka clarifies. “The metzorah had to sit alone outside the camp, the quintessential social distancing. So our work now is to draw closer to the soul of the other, to feel with the other and be aware of his needs. And that,” says Rav Shlomo Yehudah, “is the way forward, as it appears to me.”

Your Inner Truth

Rav Shlomo Yehudah was born in Eretz Yisrael in 1988, an only child born after many years. His paternal grandfather, Rav Shlomo, was a scion of the sages of Yemen and learned with the great mekubalim of Jerusalem after he arrived in the Holy Land. His maternal grandfather, Rav Yehudah, made aliyah from Aleppo, Syria.

It’s said that his pious grandmother Naomi (Rav Shlomo’s wife) poured out copious tefillos to merit a grandson. When he was born, she was overjoyed, and, realizing this child was destined for greatness, she would warn, “Guard the child and make sure that his head covering never comes off for a moment.” Savta Naomi naturally assumed that this grandson would be named for her husband — after he passed away, she saved all her money and built a shul in his memory. “I prayed for this grandson,” she said. “I want his name to be Shlomo.” But his mother wanted to name the boy for her own father, Rav Yehudah. In the end, a compromise was reached: Shlomo Yehudah. And to this day, Rav Shlomo Yehudah sees one of the missions of his life as bringing peace between people.

In our conversation, Rav Shlomo Yehudah described the poverty that accompanied him as a child. His father suffered from various ailments related to an injury, which prevented him from working, but the one comfort amid his suffering was seeing his child learning diligently. In fact, little Shlomo Yehudah would cry his eyes out when he’d read about tzaddikim, feeling a strong desire to connect to and understand the depth of their writings. When he’s asked where he had acquired such sensitivity, he’ll say: “Do you think the Tannaim and Amoraim learned the Torah just to know and remember it? They learned Torah with tears in their eyes, never missing the slightest detail or deviating an iota from the Divine Will.”

Shlomo Yehudah grasped this concept when he barely out of diapers. The family moved often during his childhood — to Spain, Switzerland, and Germany, returning intermittently to Israel. But wherever they were — in Jerusalem, Zurich, Berlin, or Barcelona — Shlomo Yehudah sought out the beis medrash, its four walls the firm ground in his life.

His unusual childhood, he relates, compelled him to get used to a complicated reality — from the time he was four years old, he lived in foreign countries where he didn’t know the language, and his seforim were his only friends. His mother would prepare him a box of cut-up fruit, which would sustain the little boy for the long day he’d spend in the local shul.

But how does such a small child experience such lofty thoughts and practices? “Difficulties in life bring a person to introspection,” Rav Shlomo says. “For me it was a result of the distress, the difficulty, the poverty, the troubles. But since I can remember — even at age three or four — I would stare up at the sky, at the stars. Today, I still do that. I make sure I’m always next to a window. When you look down or behind, you can fall, but looking up? That will always bring a person to see that he’s living for something higher.”

The family returned to Israel shortly before Shlomo Yehudah’s bar mitzvah. At the time, there was a memorial event for a relative, and the family was looking for someone to say words of Torah in honor of the deceased. His father asked him to speak before the assembled, and he agreed, out of respect — but even his father had no idea of the depth of Torah that would pour forth from his young illui. As Shlomo Yehudah lowered his head and sought the right words, the thin stream quickly grew into a powerful waterfall. People were astonished.

It was as if they were watching a child possessed. The voice was small and innocent, but the words were those of an accomplished talmid chacham — a tapestry of Chumash and Navi, Gemara and Aggadah, every source accurately cited. His father sat in a corner of the shul and covered his face to conceal the tears rolling down his cheeks.

From that point on, he was asked to deliver divrei Torah on various occasions. By the age of 14, he was already giving a Gemara shiur to adults. The shiurim were remarkable, and that was when the term “Yanuka” was bestowed on him, for he was a gaon in Torah whose tremendous breadth of knowledge belied his young age.

Another aspect of Rav Shlomo emerged at that time as well: his special connection to the world of music. “One day, he heard through a window the sound of music from someone playing a grand piano,” one of his talmidim relate. “The sounds captivated him, and he felt a deep urge to learn how to play — he prayed that he should be zocheh. Somehow his parents managed to acquire a cheap keyboard for him, and in just three hours, he figured out how to play a few tunes.”

Rav Shlomo Yehudah even composed a tefillah about music: “Vezakeinu, please grant me the merit to feel the holiness of pure music, and may holy niggunim play inside me that should awaken me and Klal Yisrael to You, yitbarach shimcha.” To this day, every Torah shiur he gives concludes with a short musical interlude. Sometimes it’s just singing, but often someone brings a keyboard to his seat at the front table and the Yanuka begins to play — he plays both his own compositions and classic tunes.

“Music connects a person to his true source,” he says. “When a person doesn’t play or sing, and in general when he’s not connected to music, he’s lacking an important component in avodas Hashem. When a person doesn’t dance or isn’t happy or doesn’t like music, he’s hiding from himself. Music can reveal the inner essence of a person and bring him to his truth.”

Everyone Can Remember

As a bochur, Rav Shlomo learned privately with Chacham Gedalia Chaim, a well-known elderly Yemenite mori and baki in all of Torah. Although Chacham Gedaliah was 65 years older than Rav Shlomo, he treated the young scholar with utmost respect, referring to him as “mori verabi.”

It wasn’t long before Shlomo Yehudah began to gain renown among the talmidei chachamim of Jerusalem. Rav Moshe Halberstam ztz”l, a venerated posek and member of the Eidah Hachareidis beis din, enjoyed speaking with him in learning, and foretold of greatness for him.

But as Shlomo Yehudah’s name began to spread, he reacted, shunning all media and fleeing from photographers. Today, Rav Shlomo Yehuda realizes that it’s unavoidable, yet even though he agreed to let our photographer do his job, he lowered his eyes and hunched into himself, clearly not one to pursue the limelight.

Part of that is because Rav Shlomo Yehudah doesn’t really see himself as special. (“When a person learns Torah to uphold the Will of Hashem, then what is there for him to be boastful about?”) Although he’s known for his phenomenal memory and can source practically kol haTorah kulah, he believes it’s within the grasp of anyone who desires to be a talmid chacham.

“The solution to retention is actually quite simple once it’s broken down,” the Yanuka explains. “It involves connecting what you learn with the inner part of your soul. If a person experiences something that frightens or distresses him, he’ll remember every detail of it, even after much time has passed. And similarly, when a person does something from a place of ahavah, he remembers that thing as well. So when we contemplate the words of Chazal, not just what they’re saying, but who they were, how they were steeped in Torah at all costs, through poverty and fear of persecution and endowed with transmitting Hashem’s Will to the future generations, we can attach ourselves to them, soul to soul, and it brings us to remember things in a way that are etched in all the layers of our mind and soul.”

Still, we want to know, is it really as simple as that? And, we ask, perhaps a bit too brazenly, how did the Rav acquire all his Torah knowledge? Is he a born genius? And how does a person attain such a breadth of knowledge at such a young age?

Rav Shlomo Yehudah appears somewhat abashed — but he doesn’t lose his composure. “If you are asking me what I always think about when I learn, the answer is that I think about my love for HaKadosh Baruch Hu. The years of solitude that I endured brought me to an intense closeness. Davening to Him and a desire to cling to Him are what brought me to toil in Torah.”

Does that necessarily mean that solitude and loneliness are a recipe for growth? And if that’s true, then does it follow that a person who has lots of friends and lots of activities will be distracted, that it will be impossible for him to be really diligent or able to climb spiritual heights?

“Distractions can definitely pull a person away from Hashem — even more than the yetzer hara,” Rav Shlomo Yehudah explains. “The Baal Shem Tov says that if a person looks in the face of someone who is not cleaving to Hashem, someone who doesn’t think about Hashem, it can cause harm to his soul. That’s why we learn in Pirkei Avos, ‘If two sit and there is no divrei Torah between them…’ What does ‘ein beineihem’ (there isn’t between them) mean? It should have said, ‘And they do not engage in Torah.’ But ‘ein beineihem’ means that they do not connect the Torah between them. It’s like, I say a devar Torah, you say a devar Torah, but we don’t feel together with the Torah. Each one says the Torah that is his and wants others to see what he knows. So we always want to make sure that the Torah is a connector. ”

Yet, as we know, not everyone has the drive, or the wherewithal, to learn. What about a person who feels he “just can’t learn”? Rav Shlomo Yehudah seems distressed by the question. After all, he says, there is no exemption from some kind of Torah learning every day. “At the same time,” he notes, “everything that a person does or learns — at any level — is precious to Hashem. Every person needs to fulfill this on his level. For example, if a person needs to engage in business, he should deal honestly and learn the relevant halachos of ribbis (interest) or of tzedakah, and he should do whatever he can based on his level. He needs to check what his abilities and strengths are, and based on that he should find a seder for this level.

“For others the answer might be to daven with more kavanah. Make brachos with more kavanah. Tell Hashem, ‘Perhaps I’m not the Vilna Gaon and can’t learn around the clock, but I’ll say my brachos and recite my tefillos with kavanah. While eating, I will think about You, and I’m doing the best I can.’ Whatever you do with your strengths, that is your uniqueness. HaKadosh Baruch Hu does not want a person to be on a level that’s not his.”

Fusing All the Parts

When Rav Shlomo Yehudah was 18, he began giving regular shiurim in different communities around the country, and it didn’t matter if you were litvish, yeshivish, or chassidish — people from all sectors began to flock to him. He married at age 20 and settled in Rishon L’Tzion, where he lives today, and where for the last ten years he’s been giving a regular shiur and trying to avoid publicity. But two years ago, in response to the directive of gedolei hador (some of whom come to his shiurim), his shiurim have gone public, in halls and auditoriums, sometimes drawing over a thousand people at an event. And there are a lot of surprises too. He often asks the crowd to pick a subject they want him to speak about — and he’s off and running, pulling together sources from all over, creating a tapestry of light and wisdom for a spellbound audience.

Rav Shlomo Yehudah’s special-occasion shiurim in the big shul in Jerusalem’s Kiryat Sanz neighborhood draw thousands of attendees. Some of the regular participants include Rav Shimon Baadani, Rav Moshe Mordechai Karp, the mekubal Rav David Batzri, and others.

And then there’s the music. At the end of this past Chanukah maamad, which drew several thousand, the Yanuka began a medley, beginning with old Chabad niggunim, segueing into Carlebach’s “Mimkomcha” and Yossi Green’s “Aderaba,” followed by more niggunei neshamah — and accompanied by Chazzan Chaim Eliezer Hershtik and violinist Daniel Ahaviel, a regular at the shiurim who often plays together with the Yanuka at the finale.

A talmid of the mekubal Rav Sroya Deblitzky ztz”l said of Rav Shlomo Yehudah: “I found what Rav Sroya was looking for all the years. The Rav wrote, ‘We needed a gadol who will unite all the parts of the holy Torah, yet, due to our great sins, we do not have someone like that in our orphaned generation.’ Yet now, we’ve merited this gift — a talmid chacham that knows all parts of Torah, and connects it to people of all streams.”

Rav Moshe Mordechai Karp of Modiin-Illit says the Yanuka is an “echad umeyuchad, singular in our generation, mara dekula Oraisa. And in his humility, he is a true vessel of kabbalas haTorah, as Rav Lavitas Ish Yavneh instructed in the Mishnah, ‘Me’od me’od hevei shefal ruach.’ ”

While Rav Shlomo Yehudah doesn’t peddle mysticism and shies away from giving brachos, Rav Shlomo Busso, a grandson of the Baba Sali and an admor in his own right, praised him at the engagement of his daughter, telling how a brachah he gave was instantly fulfilled.

“He’s a yachid bedoro, with the entire breadth of Torah — Bavli, Yerushalmi, Rishonim, Acharonim, Zohar, Midrash, everything — on his lips, and all with such a self-effacing demeanor I’ve never encountered in anyone of his stature,” said Rav Busso. And then he went on to describe his personal yeshuah: “I had approached the Yanuka several times for a brachah for a shidduch for my daughter, but he was always evasive about when the yeshuah would come. Then on Chanukah, a time of supernatural miracles, I went to him again and asked for a brachah, and this time he looked at me and said, ‘No more delays! It will come today!’ Minutes later I got a phone call with the suggestion, and a week later we made a l’chayim.”

All Paths Converge

In addition to his network of shiurim and his daily learning quota, Rav Shlomo Yehudah has also published five seforim, on Chumash, on tefillah, and on various topics culled from his shiurim. And if there’s an underlying theme to it all, it’s about the unification of the klal, of breaking down the artificial barriers that separate us and make us think it’s “us against them.”

He tells of Rav Pinchas of Koritz zy”a, who once asked the Baal Shem Tov about a particular young fellow who had strayed: How should one bring back a child who has strayed from the path? In what way? Through kavanos in the mikveh? Through yichudim? What should be done? “The Baal Shem Tov chuckled and said, ‘Only by loving him will he accept from you and you will be able to bring him back.’ And that’s what happened,” the Yanuka explains. “He displayed great love for that Jew and brought him back. It is a basic rule: Love every Jew and then we can bring all of Am Yisrael closer to our Father in Heaven.”

|

Let’s start with the basic term baal shem. It literally means “master of the Name.” It is a title often given to those who have mastered the kabbalistic names of G‑d and His angels. Through intense concentration on these names, they are capable of overriding the patterns of nature to heal the sick and rescue those in need.

|

Perhaps the reason so many, from so many sectors, are drawn to him is that he doesn’t see differences as separating — all paths lead to the same place, like the 12 gates all converging into the Beis Hamikdash. He quotes with equal enthusiasm the Rogatchover Gaon and Rav Shlomo Karliner, the Vilna Gaon to Rebbe Nachman of Breslov. So many tzaddikim, such a wide arrange of shitos and paths. How is it possible to blend all these paths?

“There is no contradiction,” the Yanuka says emphatically. “Hashem is One. The Torah is One. Anyone who learns Torah with an eye on the truth —will not find a contradiction between the various paths in avodas Hashem. When a person learns to be mepalpel, he can find all kinds of things — this one said this, that one thinks differently, there is a discrepancy in what they say. But when one learns in order to draw closer to Hashem — then you don’t see any discrepancy. On the contrary, in the end, everything blends together toward the Will of Hashem.

“We need need it all — the wisdom of Chabad, the connection of Breslov, the litvish derech of breaking through a sugya to reach the root, to connect to the Will of Hashem by delving into the depths of His Torah.”

The Yanuka’s personal learning schedule encompasses it all. He learns sifrei halachah and kabbalah, and completes Shas Bavli and Yerushalmi a few times a year, along with the entire Tanach and commentaries and midrashim. Three times a year, he conducts a big siyum — on his birthday (15 Iyar, the day the holy, spiritually nourishing man began to fall from Heaven in the desert), on Shavuos, and on Simchas Torah. Order, seder, is a crucial part of his day, which he believes is integral to any avodas hadodesh. He willingly advises talmidim when it comes to organizing a daily schedule, with goals and objectives in every area in which a person seeks to carve out a path in avodas Hashem.

In fact, we notice that this scion of Yemenite mekubalim has in front of him a kamea of sorts — a tiny locket — with a picture of the Rogatchover Gaon.

“I always keep the picture of the Rogatchover with me,” Rav Shlomo shares. “I put it on the table while I’m learning. He’s my inspiration as a symbol of true ahavas Torah. And although he was very sharp and known to be impatient in the face of ignorance, it actually came from a place of deep humility. He once gave semichah to someone who really didn’t know much, and people were shocked. They didn’t understand how the Rogatchover could do such a thing, and he explained: ‘I asked him a question and he replied that he did not know the answer but b’ezras Hashem when a case would be presented he would ask the rav in his city who would surely know….’

“Then the Rogatchover explained: ‘When I ask someone and he says he doesn’t know or he’ll look it up or he needs to think — then I can give him semichah because I know he will clarify the halachah. But when I ask a person and he tries to answer from all kinds of places — responses that are neither correct nor precise — how can I trust to give such a person semichah?’ Those were the people he spoke against sharply.”

As we ponder these words, there’s a short lull in the conversation before we get up to leave — and that’s when we hear it: All this time, there’s been soft music in the background. Only now did we realize that this soundtrack, a classic chassidic tune of yearning, was playing through our entire conversation. Now we get it: That’s Rav Shlomo Yehudah’s way — to learn Torah while the chords of his soul are playing harmony.

And this song, the song of his life, is just beginning, the rivers just starting to spread outward.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 812)

spacer

: Since the saintly Rabbi Duvid’l passed away, peace has passed away from our town. He guided the flock in his wisdom, and no one plotted to disturb the peace, even if some secretly grumbled [against him] in their tents. He knew how to navigate the ways of the community with tolerance, so quarrels wouldn’t break out, […] but today our congregation is like most other congregations of Jacob in our land: there’s no end to the fighting […].

: Since the saintly Rabbi Duvid’l passed away, peace has passed away from our town. He guided the flock in his wisdom, and no one plotted to disturb the peace, even if some secretly grumbled [against him] in their tents. He knew how to navigate the ways of the community with tolerance, so quarrels wouldn’t break out, […] but today our congregation is like most other congregations of Jacob in our land: there’s no end to the fighting […].

IS THIS THE GUY THE RABBI´S ARE TALKING TOO???

IS THIS THE GUY THE RABBI´S ARE TALKING TOO??? KADURI´S PROPHECY COMING TO PASS NOW!!!

KADURI´S PROPHECY COMING TO PASS NOW!!!

VIDEO IS HERE

VIDEO IS HERE

MY NEW BACK-UP CHANNEL IS HERE:

MY NEW BACK-UP CHANNEL IS HERE:

Subscribe to help us reach 1 Million Subscribers:

Subscribe to help us reach 1 Million Subscribers:  ROMANS

ROMANS  Salvation Prayer Dear Jesus, I know I am a sinner. I pray that you will forgive me for all of my sins, that you will come into my heart and be my Lord, the savior of my life. I confess that you died on the cross to save me from my sins and I am committed to turning away from those sins. I ask that you fill me with your Holy Spirit so that I can be born again. I ask that you give me the strength and abundant faith to overcome any and all attacks by the enemy, including my desire to sin so that I may serve you completely. I pray that you will give me discernment so that I may know all things that are truth, and the knowledge acquired from reading your Word. Use me this day as I am a willing vessel Lord, in leading others to your kingdom. Wash me as white as snow. Put a hedge of protection around me as I go forth in doing your will. Thank you Jesus for saving me, as I know that only through my faith in you that all this is possible. Amen! The information on this wallytron101 YouTube Channel and the resources available are for educational and informational purposes only. COPYRIGHT “Copyright Disclaimer Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing. Non-profit, educational or personal use tips the balance in favor of fair use.” NEWS – EDUCATION – SCIENCE – END TIMES 2022 – END TIMES NEWS REPORT – MIDDLE EAST UPDATE – BIBLE PROPHECY – END TIMES PRODUCTIONS – LATEST NEWS

Salvation Prayer Dear Jesus, I know I am a sinner. I pray that you will forgive me for all of my sins, that you will come into my heart and be my Lord, the savior of my life. I confess that you died on the cross to save me from my sins and I am committed to turning away from those sins. I ask that you fill me with your Holy Spirit so that I can be born again. I ask that you give me the strength and abundant faith to overcome any and all attacks by the enemy, including my desire to sin so that I may serve you completely. I pray that you will give me discernment so that I may know all things that are truth, and the knowledge acquired from reading your Word. Use me this day as I am a willing vessel Lord, in leading others to your kingdom. Wash me as white as snow. Put a hedge of protection around me as I go forth in doing your will. Thank you Jesus for saving me, as I know that only through my faith in you that all this is possible. Amen! The information on this wallytron101 YouTube Channel and the resources available are for educational and informational purposes only. COPYRIGHT “Copyright Disclaimer Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing. Non-profit, educational or personal use tips the balance in favor of fair use.” NEWS – EDUCATION – SCIENCE – END TIMES 2022 – END TIMES NEWS REPORT – MIDDLE EAST UPDATE – BIBLE PROPHECY – END TIMES PRODUCTIONS – LATEST NEWS MESSIAH IS HERE – ISRAEL´S NOT OURS!!!

MESSIAH IS HERE – ISRAEL´S NOT OURS!!!

PLEASE JOIN OUR TEAM HERE:

PLEASE JOIN OUR TEAM HERE:

Another Eye opening Must Watch Video

Another Eye opening Must Watch Video

(Source:

(Source: