Werewolf Syndrome. Something that has apparently been a huge focus for science and medicine over the past few decades. They would like you to believe that they are looking for a cure for baldness, but in truth they are fascinated by Werewolves. Yes, werewolves do exist and have throughout history. I think they are looking for a way to create werewolves. They have been studying those who have the physical features in their genes.

There is an element required for a true werewolf and that is a spiritual aspect. One must be opened to the demon. They are working on that end as well. We have reached a time in history when most of the world is call up demons knowingly and out of ignorance. We have also reached a time when the elite have or soon will have unlimited access to our bodies and minds.

In this series of posts, I hope to help you to discern that they are working with very powerful demonic forces to cause the masses to become changelings/shapeshifters and hybrids. Anything that takes us out of the Kingdom of GOD and places us at the mercy of Lucifer/Satan/The Devil.

GENETIC MANIPULATION is the MOST EVIL activity in which humans can possibly involve themselves. It is the CRIME for which the God of the Bible would not forgive the Fallen Angels. I knew when I first read about CRISPR that this would bring about the end of humanity. Genetic Manipulation plays a very big role in today’s post.

The OPEN MIND video regarding GENETIC MANIPULATION discussing the topic and concerns the public had raised about the safety and ethics of this technology aired on 01/10/83 – 40 years ago. 40 years as of this year. A generation in the Bible is typically considered to be 40 years.

Luke 21:32. Truly I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things take place

Now, since the public was already “concerned” about the ethics of this technology, than you know it has been practiced already far beyond 40 years. As you read through today’s post pay attention to the dates.

spacer

RELATED POST:

Children infected with Werewolf syndrome?

spacer

If you have not seen my posts on CRISPR technology you can find them HERE:

spacer

CRISPR – Part 1- GENETIC MANIPULATION the Springboard

CRISPR – Part 2- The DESTROYER

CRISPR – Part 3- THE ULTIMATE END

CRISPR – Part 4 – Unleashed

Crisper’s Progression – GOD HELP US

spacer

The rare hereditary condition, called congenital generalized hypertrichosis, results in such a furry appearance from birth that scientists propose it could be an example of an atavistic mutation — the re-emergence of an evolutionarily ancient trait that is normally kept suppressed. In this case, the mutation harks back to the prototypically mammalian state of near-total hirsutism, the possession of a protective fur coat that modern humans for some reason lost at an unknown point in the past.

In fact, those with generalized hypertrichosis — hyper meaning excess, and trichosis, hair — are even hairier than chimpanzees or gorillas, which lack fur around the cheeks, nose and eyes. The only parts of the patients’ bodies without hair are the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. This suggests that the atavism could recall something earlier than the emergence of hominoid apes about 25 million years ago.

“This is probably a mutation of a gene that was a sleeping beauty,” said Dr. Jose M. Cantu, head of genetics at the Mexican Institute for Social Security in Guadalajara, an author of the new report. “The mutation awakened a gene that had been put aside during evolution.”

But Dr. Cantu and his colleagues emphasized that the idea of generalized hypertrichosis as an atavistic mutation was only a theory. “At this point it’s strictly speculation, though the idea is a very interesting one,” said Dr. Pragna I. Patel of the Human Genome Center at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, another author of the report, which appears in the June issue of Nature Genetics.

Biologists have observed many other mutations that they suggest fall into this class of atavisms, the reappearance of normally dormant traits. Some people are born with multiple sets of nipples, for example, just as most nonprimate mammals have a double ridge of mammary tissue down the length of the underside of the torso. In very rare cases, girls develop entire extra breasts at puberty.

“Atavistic mutations tell us that a lot of information is kept around for a very long time,” said Dr. Brian K. Hall, a developmental biologist at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. “Just because an animal isn’t using a gene anymore doesn’t mean the information just disappears.” Dr. Hall wrote a commentary about atavistic mutations that appears with the report on hypertrichosis.

The researchers do not yet have the precise gene isolated, but merely know its approximate location, on the bottom half of the X chromosome. They found the location by examining the genetic material of a large Mexican family, whose members may be the only humans known to have this particular mutation.

spacer

THOMAS H. MAUGH II

Scientists are close to identifying a hair-growth gene responsible for an extremely rare disease that is probably the source of ancient werewolf legends, a finding that serves as a dramatic reminder of humans’ evolutionary proximity to their animal predecessors.

The disease, called congenital generalized hypertrichosis, is characterized by excessive amounts of hair on the face and upper body. When the hair is shaved off, however, victims appear normal, thereby fostering the belief that werewolves were seemingly normal people who underwent a mysterious metamorphosis in the light of a full moon.

Verified victims of the disease, who have numbered perhaps 50 since the Middle Ages, have often worked in circuses as “ape men,” “wolf men” or “human werewolves.”

Although identification of the gene may have little practical value for victims of the disorder, it may shed much more light on the regulation of hair growth, a subject about which scientists know surprisingly little. That, in turn, could eventually lead to new treatments for baldness.

Once scientists learn “what the gene is and how it works, we will have gone a long way toward understanding the causes of baldness in people,” said developmental biologist Gail Martin of UC San Francisco. “That has tremendous psychological and commercial value. Hair growth is very important to people.”

Members of an international team headed by molecular geneticist Pragna I. Patel of the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston report today in the journal Nature Genetics that they have narrowed the location of the gene to a small region of the X chromosome, one of the two sex-determining chromosomes.

Their search for the precise location is proceeding slowly, however, because they have not been able to identify enough victims of the disorder to use conventional gene identification techniques. All of their studies have been conducted on one Mexican family that has 18 affected members.

The excessive hair growth caused by the disorder is probably a typical example of what scientists term an atavistic genetic defect–a mutation that unleashes a gene that has been suppressed during evolution. Human ancestors were once covered with hair from head to foot.

spacer

| You can read more about how it has affected this family by clicking on the Article Title below: |

|

Curse of the Wolf Family: From circus freaks to being branded ‘Satanic Beasts’, the ‘hairiest family in the world’ reveal how they have struggled to survive bullying, poisoning and persecution |

During the course of evolution, they did not actually lose the gene that produced the excessive hair, researchers believe. Instead, the normal activity of that gene was curtailed. The defect in the Mexican family simply allows that gene to function once again.

(Now, use your brain. If this was evolution, than all humans or at least more humans would have the gene latent in their system. This occurs only 1 in a billion people. This is not evolution. This is something else. Gene manipulation. We know that the Fallen Angels practiced and taught gene manipulation to mankind. It could also be the result of humans having sexual relations with demons.)

“Atavisms–long an embarrassment to evolutionary biologists–are now seen as potent evidence of how much genetic potential… These atavisms serve as reminders that genetic characteristics do not get lost during evolution, but simply become latent, awaiting the opportunity to re-emerge, molecular biologist Brian Hall of Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada, notes in the same journal.

The hypertrichosis disorder was identified in the Mexican family and named in 1984 by Jose Maria Cantu and his colleagues at the University of Guadalajara, a team that has identified more than 40 rare genetic syndromes. Many of those syndromes also have excessive hair growth, but it usually accompanies other genetic problems.

By studying its pattern of inheritance, they were able to determine that the hair growth is a so-called X-linked dominant trait. Males pass the gene on only to daughters, while females pass it on to both daughters and sons. Furthermore, the pattern of hair growth in females is very patchy, a characteristic normally associated with X-linked defects.

The team used conventional techniques to narrow their search to a small region of the X chromosome, but that region still contains many genes. They are stymied now because those same techniques require identification of other families with the disorder to further narrow the search, and they have not yet found other families. (so they decided to make some.)

“Defects in hair growth genes are extraordinarily rare,” Martin said. The best hope, Patel concluded, lies in the efforts of the Human Genome Project to identify all the genes on the X chromosome. Once that is accomplished, her team can look at each of those genes and determine which ones are involved in hair growth.

During the course of evolution, they did not actually lose the gene that produced the excessive hair, researchers believe. Instead, the normal activity of that gene was curtailed. The defect in the Mexican family simply allows that gene to function once again.

spacerspacer

Julia Pastrana was history’s most famous bearded lady. In the 19th century, she fascinated spectators as part of a traveling circus, dancing and singing in clothes that showed off her hairy visage and limbs. In 1857, The Lancet documented Pastrana as a “peculiarity,” but modern medicine shows that she suffered from a real disorder known as congenital generalized hypertrichosis terminalis (CGHT), sometimes called “werewolf syndrome.” Now, Chinese scientists have begun to unravel the genetic story behind her condition.

CGHT is an extremely rare but highly heritable disorder. Scientists are unsure how many people have the condition, but there are at least 30 cases in China’s billion-strong population. Affected men and women develop excessive dark hair across their bodies and faces. Some sufferers also have a broad, flat nose, large ears, a large mouth, and thick lips, and, occasionally, an enlarged head and jaw.

Hoping to discover the genetic basis of CGHT, geneticist Xue Zhang of the Peking Union Medical College in Beijing scoured his country for cases of the disease. After 4 years of searching through medical literature, the Internet, and even television, his team found three affected families, including 16 afflicted members willing to participate in the study. The researchers scanned the DNA of these individuals and compared it with the DNA of 19 family members without CGHT. After narrowing down the search to a short section on chromosome 17, the team looked for mutations called copy number variations, in which large chunks of DNA are repeated or removed. All of the CGHT sufferers had a copy number variation in which DNA was deleted across the same four genes, the authors report today in the American Journal of Human Genetics. None of the unaffected family members had the mutations.

Zhang speculates that the mutations change the local structure of the chromosome, interfering with the production of nearby genes. Indeed, one neighbor, SOX9, is linked to hair growth: Mice without it are known to suffer from hair loss, or alopecia. If the CGHT mutations somehow alter this region of chromosome 17 so that the SOX9 protein is overproduced in hair follicle stem cells, this would cause excessive hair growth, says Zhang. “But all this is pure speculation,” he says.

Zhang may be onto something, says Eli Sprecher, a hair disorder expert at the Rappaport Institute in Haifa, Israel. Another hair-overgrowth condition-–Ambras syndrome–has been linked to chromosomal rearrangements, he notes, so it’s plausible that CGHT works the same way. This study is “a first and important step” toward solving the puzzle of this disease, he says.

Scientists Find ‘Werewolf’ Gene

Supatra “Nat” Sasuphan, the world’s hairiest child. (Guinnessworldrecords.com)

Scientists have discovered a genetic mutation responsible for a disorder that causes people to sprout thick hair on their faces and bodies.

Hypertrichosis, sometimes called “werewolf syndrome” is a very rare condition, with fewer than 100 cases documented worldwide. But researchers knew the disorder runs in families, and in 1995 they traced the approximate location of the mutation to a section of the X chromosome (one of the two sex chromosomes) in a Mexican family affected by hypertrichosis.

Men with the syndrome have hair covering their faces and eyelids, while women grow thick patches on their bodies. In March, a Thai girl with the condition got into the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s hairiest child.

A man in China with congenital hypertrichosis helped researchers break the case. Xue Zhang, a professor of medical genetics at the Peking Union Medical College, tested the man and his family and found an extra chunk of genes on the X chromosome. The researchers then returned to the Mexican family and also found an extra gene chunk (which was different from that of the Chinese man) in the same location of their X chromosomes. [Top 10 Worst Hereditary Conditions]

The extra DNA may switch on a hair-growth gene nearby, resulting in runaway furriness. The best bet for a culprit, wrote study researcher Pragna Patel of the University of Southern California, is a gene called SOX3, which is known to play a role in hair growth.

“If in fact the inserted sequences turn on a gene that can trigger hair growth, it may hold promise for treating baldness or hirsutism [excessive hair growth] in the future, especially if we could engineer ways to achieve this with drugs or other means,” Patel said in a statement.

The study is detailed in the June 2 issue of the American Journal of Human Genetics.

Scientists discover ‘werewolf’ gene which could spell the end for baldness

A ‘werewolf’ gene which causes hair to grow all over the body has been found by scientists, who say the discovery could lead to a remedy for baldness.

They have tracked down a genetic fault which is behind a rare condition called hyper- trichosis, or werewolf syndrome, where thick hair covers the face and upper body.

They say they may be able to use drugs to trigger a similar gene mutation in people to encourage hair to grow on bald patches.

Breakthrough: Scientists have identified a genetic fault called hyper-trichosis which could, in time, spell the end for baldness

But the scientists stressed that tackling baldness was still many years away.

They do not yet know how they would be able to trigger hair to grow in bald patches without causing excessive growth all over the body.

Werewolf syndrome is extremely rare, with only 50 recorded cases in the past 300 years.

One is Supatra Sasuphan, an 11-year-old girl from Thailand who was named as the world’s hairiest child in the Guinness World Records in March.

Men with the condition have hair all over their face, including eyelids, and upper bodies.

Women tend to just have hair in patches although Supatra has it covering much of her face.

Example: Thai schoolgirl Supatra Sasuphan suffers from the genetic fault known as werewolf syndrome, which causes hair to grow on her face

Scientists from the University of Southern California, working with researchers from Beijing, discovered the gene in a Mexican family and Chinese family who both had the condition – known in the medical world as CGH.

Professor Pragna Patel, of the university’s Institute for Genetic Medicine, said certain genes appeared to have been ‘turned on’, which may trigger the excessive hair growth.

In the future, scientists could use drugs to ‘turn on’ genes, which could trigger hair growth.

Professor Patel added: ‘If in fact the inserted sequences turn on a gene that can trigger hair growth, it may hold promise for treating baldness.’

The Curious Genetics of Werewolves

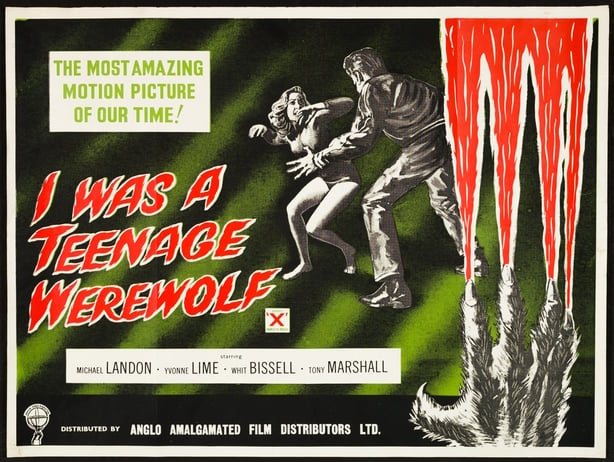

Growing up in the 1960s, I collected monster cards: The 60-foot-man and the 50-foot woman, duplicate bodies gestating in giant seed pods, unseen Martians that sucked children into sand pits and returned them devoid of emotion, with telltale marks on the back of the neck. One card featured a very young Michael Landon in “I Was a Teenage Werewolf.”

Forgive my lapse in political correctness, but I recalled those cards when I saw the word “hypertrichosis” in a recent paper in PLOS Genetics, because, unfortunately, the condition is also known historically as “werewolf syndrome.”

In the paper, geneticist Angela Christiano, PhD, and colleagues at Columbia University analyzed the genomes of a father and son with Ambras syndrome, a form of hypertrichosis – and found something intriguing about the causative mutation that has repercussions for genetic testing in general.

A WEREWOLF PRIMER

Before a genetic explanation for overactive hair follicles existed, werewolfism, aka lycanthropy, was thought to arise in eclectic ways: rubbing a magic salve into the skin, sleeping outdoors under a summer full moon, drinking from the pawprint of a wolf, or a devil’s curse. Werewolves were once considered to be giant extinct lemurs from Madagascar.

Armenian folklore describes a werewolf as a female criminal being punished by coming out at night and eating her children, and then her relatives’ children, in order of relatedness.

In 1963 a physician in London, where Warren Zevon tells us werewolves are prevalent, ascribed lycanthropy to the very rare blood disease congenital erythropoietic porphyria. With its attendant hairiness, reddish teeth, pink urine, and aversion to bright light, porphyria would later explain vampires too, although that idea has been discredited.

Some physicians suggested that hypertrichosis causes lycanthropy, but others argued that the genetic condition was too rare to account for the many werewolves loose on the streets of Europe.

ONLY 50 CASES KNOWN

Sources say that Ambras syndrome affects fewer than one in a billion people, and that only 50 cases have been described since the Middle Ages.

The name Ambras comes from Petrus Gonzales, who at age 12 in 1556 was brought as a slave from Tenerife in the Canary Islands to the court in France. He had a strikingly hairy face, married young, and had 4 children, 3 of whom were born hairy. His daughter Tognina and son Arrigo passed on the trait. Royalty, who called Petrus the “man of the woods,” thought he represented a race of hairy people  from the Canary Islands. The celebrated family sat for many portraits, and one, displayed at a castle near Innsbruck called Ambras, led to their notoriety as the “family of Ambras,” and eventually their condition as “Ambras syndrome”. (An image of a little girl from the family graces the cover of Armand Marie Leroi’s fabulous book Mutants).

from the Canary Islands. The celebrated family sat for many portraits, and one, displayed at a castle near Innsbruck called Ambras, led to their notoriety as the “family of Ambras,” and eventually their condition as “Ambras syndrome”. (An image of a little girl from the family graces the cover of Armand Marie Leroi’s fabulous book Mutants).

Shwe-Maong was another noted person with Ambras syndrome, from Burma. Wrote an observer in 1826: “… the whole face, with the exception of the red portion of the lips, were covered with fine hair.” The hairs were 4 to 8 inches long, straight and silky.

Born in the hill country outside the capitol, people encouraged Shwe-Maon to whoop like a monkey and act dumb. Like Petrus, he became a royal favorite, given a wife at a young age. They had 4 children, including a girl whose entire body was covered in a pelt of long, silky grey hair. Her name was Maphoon. She married and had two hairy sons, one of whom passed on the trait.

Charles Darwin mentioned Maphoon in The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (1859), but it was his readers who brought up that the striking hairiness was atavistic, a turning-on of an ancestral trait silenced through evolutionary time. But the quality of the hair isn’t like that of an orangutan or gorilla. It‘s silky, and covers places, especially on the face, where our ape cousins don’t have hair. People with Ambras syndrome aren’t throwbacks.

Some individuals with Ambras syndrome ended up in circus sideshows, such as Julia Pastrana, the “bearded lady” who toured Europe and North America in the 1850s. In 1884 PT Barnum exhibited 16-year-old Fedor Jepticheff as “Jo-Jo the dog-faced man,” who became the inspiration for Disney’s Beast and a Phish song. Jo-Jo played along, barking on cue for PT Barnum, although he was very intelligent and made quite a good living from his genetic misfortune.

Documentation of Ambras syndrome appears in the medical literature a generation after Jo-Jo, when Russian dermatologist Nikolai Mansurov (1834–92) took photographs and commissioned wood carvings to illustrate an article on “hairy people,” then called polytrichia.

Lycanthropy may also be a delusion. A report in the November 1975 issue of the Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal described 20-year-old Mr. H, who claimed that after ingesting strychnine in a forest in Europe while serving in the military, he suddenly grew fur on his face and hands and was overwhelmed with a craving to eat live rabbits.

People with Ambras syndrome still occasionally make the news. In 2011 the Guinness Book of World Records listed Supatra (“Nat”) Sasuphan, a 12-year-old from Thailand, as the “world’s hairiest girl.” She considers this a step up from being called “wolf girl” and “monkey face.” Since her birth, long silky grayish hair has cascaded down her face, like a veil starting at her bushy eyebrows.

Earlier this year a mother and her 3 children taunted for their “werewolf syndrome” sought help in Nepal and YouTube

features several other families with Ambras syndrome.

BACK TO BIOLOGY

Ambras syndrome is a disruption of the crosstalk between the epidermis and the dermis as hair follicles form in the 3-month fetus at the eyebrows and spread down to the toes. Signals from the dermis send the messages to form follicles. As a follicle forms, it sends signals to prevent the area around it from also becoming a follicle, establishing equal spacing of our 5 million or so follicles. Most body parts ignore the messages to form follicles, and so we’re relatively hairless.

An area called the bulge about halfway down each follicle houses the stem cells that keep hair growing. Hairs cycle through phases. In anagen (growth phase) cells divide, for 2 to 6 years. In catagen, which lasts about 2 weeks, the follicle renews itself. Telogen is a 1-4 month long rest. About 85% of our hairs are in anagen at any given time, 10-15% in telogen, and a few in the transitional stage of catagen.

Human hairs are of a different quality in the scalp, brows, lashes, and pubic area. And our hair is of three basic types. Lanugo is the fuzz that coats a fetus, and may cling to the newborn. Vellus is the fine and light hair on most of the body, seen on the arms and faces of children. Terminal hair, the third type, is on the scalp and forms the eyebrows and lashes.

In Ambras syndrome, vellus hair streams down the face and curls from the ears, flowing down the shoulders. Facial features are coarse, the nose long, and the face triangular. Teeth may be absent, fingers and nipples extra.

THE BIGGER PICTURE – WHEN IS A MUTATION A MUTATION?

Since the official naming of Ambras syndrome in 1993, several studies have implicated a site on the short arm of chromosome 8, where individuals had inverted or deleted genetic material.

The responsible gene, Trps1, is a zinc finger transcription factor that regulates a suite of genes involved in hair and bone development. One of the genes it regulates is Sox9, which in turn regulates stem and progenitor cells in the bulge region of the developing hair follicle.

In a 2004 paper, Dr. Christiano and colleagues described a “position effect” behind Ambras syndrome. That is, DNA elsewhere can alter the expression of Trps1, and that of the genes it controls. Their 2012 paper unravels the genetic controls behind the position effect.

Whole genome SNP arrays on a father and son with Ambras syndrome revealed a 1½-million-base-long duplicated stretch of DNA between Sox9 on chromosome 17 and the chromosome tip, like a repeated paragraph near the end of a book. And so the position effect is on one of the genes that Trps1 regulates.

The idea of a position effect isn’t new – I remember it from my Drosophila days in the 70s; fly eyes had patches of different colors because a gene had been moved to a different chromosomal address. Position effects could cause problems with the interpretation of sequenced genomes.

The key word is sequence, because the classic Ambras cases with inverted chromosome 8s and the variegated fly eyes indicate that a gene’s neighborhood affects what it does. Copy numbers also affect gene expression – like the big duplication in the Ambras father and son who have normal Trps1 genes. Genome sequencing technology is beginning to include copy number variant analysis, but detecting rearrangement breakpoints – such as inversions and translocations — is still a challenge, and in fact recently complicated the sequencing of fetal genomes.

The Ambras position effect reminds me of another recent paper that found the opposite: “Deleterious- and Disease-Allele Prevalence in Healthy Individuals: Insights from Current Predictions, Mutation Databases, and Population-Scale Resequencing.”

As part of the 1000 Genomes Consortium, researchers checked the genomes of 179 people against mutation databases. And it turns out that even healthy folk have lots of mutations. Apparently redundancies built into our genomes can protect us.

Here’s the deal:

a. You can have a mutation (a disease-causing genotype), yet not be sick.

b. You can be sick, yet not have the associated disease-causing genotype.

c. You can be sick and have a causative mutation.

d. All of the above, for many different genes

So just as people are starting to get their genomes sequenced as prices tumble, uncertainty, albeit based on long-known concepts of genetics, blooms. And unfortunately people taking direct-to-consumer genetic tests, or even some health care professionals who are asked to interpret test results, may not be all that familiar with the fact that DNA science doesn’t always yield clear answers.

Will a consumer using testing websites learn enough about the subtleties of genetics to realize that a test result is not a crystal ball? Will the increasing delivery of genetic counseling services via videos or the phone suffice to convey the inherent uncertainty?

Like any pioneers, the first few thousand people to have their genomes sequenced will get a lot of this gray-area information. But the only way we’re going to learn what all of our gene variants mean is to decipher all possible gene interactions, and all possible perturbations, including sequences, copy number variants, and rearrangements. And that will require many more genome sequences.

If genetic analysis is not clear cut for a phenotype and inheritance pattern as obvious as those of Ambras syndrome, how will we understand the many common conditions that reflect the inputs of many genes, interacting in ways we may not yet even understand?

As in all things scientific, and despite the evolution of genetics into a medical science, the more we learn, the more we realize we do not yet know.

spacer

Hair today, gone tomorrow: Chinese girl with rare genetic ‘werewolf’ syndrome to receive treatment

A four-year-old girl suffering from a condition leaving her body covered in hair, is set to receive treatment to beat her illness.

Jing Jing has a genetic disease which has resulted in thick black hair growing not just on her head, but also on her face and body.

Now, doctors at a plastic surgery hospital in Changsha, capital of southern China’s Hunan Province have offered to help the little girl.

Help: Jing Jing, aged four, is covered in excess hair as a result of a genetic condition, but is now set to receive treatment to cure her

Treatment: Jing Jing suffers from a form of Hypertrichosis causing thick black hair to grow all over her body

Little Jing Jing’s mother appeared at the hospital in Changsha, thanking the medical experts who promised help to her daughter.

Jing Jing has a form of Hypertrichosis universalis, a genetic mutation in which cells that normally switch off hair growth in unusual areas, like the eyelids and forehead, are left switched on.

Hypertrichosis sufferers like Jing have abnormal hair growth on their bodies and faces, and in the case of females an appearance of having a beard.

It is thought that it may take up to two years for Jing Jing to complete treatment.

Grateful: Jing Jing’s mother speaks at a press conference at the hospital in Changsha, thanking the doctors who promised help to her daughter

Saved: Jing Jing begins treatment, although doctors say it may take up to two years before she is cured

I searched and searched and could not find any reporting on the treatment and how it went.

spacer

Vampires, Zombies & Werewolves, Oh My! The Origins of Halloween Monsters

Werewolves

Remus Lupin in the “Harry Potter” movies, Jacob Black in the “Twilight” series, Scott Howard in “Teen Wolf” — these are just a few of the best known werewolves from books and movies. But like zombies and vampires, shape-shifting human-wolf hybrids have quite a long history in the folklore of many nations.

Tales of werewolves appear in the nearly 2,000-year-old writings of the ancient Roman novelist Petronius, and in Ovid’s narrative poem “The Metamorphoses.” But even “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” a Babylonian tale that is nearly 4,000 years old, might mention a werewolf. In the epic poem, a goddess turns a shepherd into a wolf (a similar thing happens in Ovid’s tale). But regardless of when, exactly, werewolves were first written about, belief in these creatures remained strong throughout the Middle Ages in Europe.

In some parts of the world, popular legends depict people taking the form of other animals. In some Asian countries, like Japan and Korea, there are myths about were-foxes. In India, were-snakes are a popular element of traditional folktales.

Known as lycanthropes by some, werewolves are usually “born” in popular legends when people are bitten by a wolf or werewolf or are cursed by someone. But even seemingly innocuous things were once believed to turn people into flesh-craving human-wolf hybrids, according to the book “Giants, Monsters, and Dragons,” (W.W. Norton & Co., 2001) by folklorist Carol Rose. So take care this Halloween, because if the legends are true, even just falling asleep under a full moon or eating certain herbs can turn you into a werewolf.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

For the last eight months, farms near Kisarazu City in Japan have been home to a horrifying robot wolf. But don’t worry, it wasn’t created to terrorize local residents (although, from the looks of the thing, it probably did). Its official name is “Super Monster Wolf,” and engineers designed it to stop animals from eating farmers’ crops.

In truth, the story of the robowolf is more than a little sad. As Motherboard reports, wolves went extinct in Japan in the early 1800s. The cause? A state-sponsored eradication campaign. Now, parts of Japan are overrun with deer and wild boar. They love to feast on farmers’ rice and chestnut crops. Obviously, farmers do not love this. Fast forward 200 years, and humans create a robotic wolf to replace the species they killed off.

But there is some good here. The first official trial of the robot wolf just ended and – surprise! – it was a resounding success. In fact, it was such a success that the wolf is entering mass production next month, Asahi Television reports.

Ultimately, the trials revealed that the wolf has an effective radius of just about one kilometer (.62 miles), making it more effective than an electric fence, Chihiko Umezawa, of the Japan Agricultural Cooperative, told Chiba Nippo news. Anything outside that? You’ll have to invest in a few as, currently, the wolf is immobile.

Still interested in something better than a traditional scarecrow? If you want a robowolf of your own, you can snag one for about 514,000 yen ($4,840). The price is, admittedly, a bit steep; however, the company has more affordable monthly leasing options. Of course, it would have been far cheaper to just not eradicate an entire species, but it’s a little late for that.

The beast measures in at 65 centimeters (2.2 feet) in length, which is about the same size as an actual wolf. It also has tufts of gangly hair and an impressive set of white fangs. It uses solar-rechargeable batteries to sustain itself, and it detects intruders with its infrared ray sensor.

According to the BBC, once the robot wolf senses a creature nearby, it uses a wide range of sounds, including a gunshot, a howl, and a human voice, to frighten away the would-be diner. Of course, any humans who are unfortunate enough to stumble into the vicinity are also likely frightened away by claps of gunshots, but I suppose that is the price we must pay for modern conveniences.

MEGAN: I have been working up a STAT pitch on this movie for months. This movie features both science (my beat) and The Rock looking contemplatively out over a cornfield (my aesthetic). My original idea was to review the movie with an expert in genome-editing. I actually invited four CRISPR experts, all of whom were “busy.” Dejected, I then invited Drew.

ANDREW: Fifth choice, I’ll take it.

MEGAN: So the movie opens with a title screen that reads: “In 1993, a breakthrough new technology, known as CRISPR, gave scientists a path to treat incurable diseases through genetic editing. In 2016, due to its potential for misuse, the U.S. Intelligence Community designated genetic editing a ‘Weapon of Mass Destruction and Proliferation.’”

It was a huge relief to see CRISPR mentioned right from the get-go, because I really sold this story to our editors. It also made me feel better about expensing Sour Patch Kids and Raisinets.

ANDREW: To get technical for a second, the title screen is sort of accurate. Yes, James Clapper, then the director of national intelligence, did list genome-editing as a threat in 2016. But when I saw the 1993 line, I kind of chuckled to myself. At first, I thought, sorry, Jennifer Doudna and Feng Zhang, apparently The Rock beat you by like 20 years, your patent claims are worthless. But then I thought more about it and realized what they were referring to. This history of modern CRISPR discovery does, by some accounts, date back to 1993, even though the term CRISPR wasn’t used for another decade or so. And the title page suggests that scientists were using the system to edit genomes 25 years ago, which we know was not the case — that’s a much more recent feat. Anyway, I’ll get off my soapbox now.

Megan, to my surprise, the movie started in space. What’s up with that?

MEGAN: I was not surprised whatsoever that this movie started in space. But, essentially, an evil company is testing CRISPR in space on a lab rat. Only the rat becomes a gigantic rat, the space shuttle explodes, and three CRISPR vials fall to earth. Enter Dwayne Johnson and his best friend, George, the albino gorilla he rescued from poachers and who he communicates with using sign language.

George and two other animals — a wolf and a crocodile — are “infected” with CRISPR. It makes them grow to gigantic proportions and become very aggressive. And in the wolf’s case, it also grew bat wings. But that’s not exactly how CRISPR works.

ANDREW: I knew this movie was going to be good when one of the astronauts who is trying to escape the shuttle is frantically radioing back to earth. Someone over the radio chimes in that “the test subject is a rat,” and the astronaut replies, “Not anymore.”

And, yes, that’s not exactly how CRISPR works, but it’s not completely off base either! The idea is that the biotech company “weaponized” CRISPR research and introduced the genes of a bunch of other animals into our three monster-animals to give them traits such as those bat wings, or the spikes of some other animal, or the strength or regenerative abilities of certain kinds of bugs. This is all explained very quickly in some exposition by our disgraced yet heroic geneticist played by Naomie Harris (whom I last saw in “Moonlight,” and here’s hoping that, like that movie, “Rampage” scores a surprise best picture win at the Oscars). “I’m talking about extremely specific results,” says Naomie, who, in my mind, I am on a first-name basis with.

One question I have is whether these animal features are polygenic as opposed to tied to one gene. That would make it a lot harder to introduce them into another species. But scientists have CRISPR’d beagles to make them super jacked, so it’s not insane that CRISPR could be used to change the features of an animal. Whether it could be used to double the size of a gorilla overnight, well, that might be a different story. And for the beagles, the CRISPR’ing happened when the dogs were embryos, not fully grown.

The science of werewolves

Fishermen discover werewolf corpse in river

However, it is interesting to consider some real medical conditions which have helped to shape the traditions and rules of werewolf mythology.

Hypertrichosis

Hypertrichosis is a medical condition which results in excessive body hair growth on different parts of the body. Although it is rare, there have been several notable cases throughout history, including Fedor Jeftichew and Annie Jones who became famous as ‘Jo-Jo the Dog-faced Man‘ and ‘The Bearded Lady’ respectively in PT Barnum’s travelling circus.

In recent times, the best known and studied cases are the Wolf Family of Mexico, several of whom suffer from an inherited congenital form of hypertrichosis. Genetic analysis of their DNA has identified shared abnormalities on the X chromosome which affects genes which can control hair growth. Similar research on other affected individuals identified other genes that can cause the condition.

BBC News report on the wolf family of Mexico, several of whom suffer from an inherited congenital form of hypertrichosis

Scientists propose that these genes were gradually switched off as humans evolved from ape-like creatures, resulting in less body hair. Somehow, these have been reactivated in congenital hypertrichosis sufferers, but the exact mechanism remains unclear.

Rabies

Rabies is a deadly disease typically transmitted to humans by a bite from an infected animal, such as a rabid dog. Rabies is caused by a virus carried in saliva which targets cells in the brain and central nervous system. As these cells become increasingly infected, sufferers begin to exhibit aggressive behaviour, develop muscle spasms, experience hallucinations and produce excess saliva, causing frothing at the mouth. The similarities between these symptoms and the stages of werewolf transformation are evident.

Likewise, the idea of lycanthropy as an infection contracted from the bite of another werewolf seems likely to have its origin in the way rabies spreads to humans. Without medical knowledge, it is easy to see how our ancestors would have turned to supernatural explanations for this transmissible animal “curse”.

A brief history of werewolf mythology

Clinical lycanthropy

Clinical lycanthropy is a recognised psychological disorder in which sufferers believe they are becoming a wolf and behave accordingly. It is a very rare condition that can be classified as a Delusional Misidentification Syndrome (DMS), a group of neurological illnesses in which patients perceive dramatic changes in the appearance of people or places.

Recent evidence from DMS studies suggest the cause lies in an area of the brain concerned with self-recognition and perception of one’s own body. For example, neuro-imaging of individuals diagnosed with clinical lycanthropy showed this region of the brain displayed abnormal neuronal activity, which seemed to cause the delusions about their physical appearance. Despite these advances, it is still a poorly understood disorder, although the psychiatric therapy administered nowadays represents progress from lycanthropy treatment in the Middle Ages, when sufferers were presumed to be possessed by the devil and were therefore burnt at the stake.

Puberty

Although parents of teenagers may disagree, puberty is not generally considered a medical disorder. Nevertheless, werewolf myths have proven a ripe metaphor for the changes associated with adolescence, including aggressive behaviour, heightened sexual emotions, muscle development and emerging body hair.

Furthermore, parallels between the lunar cycle of the werewolf and the onset of the monthly menstrual cycle has often been used to add symbolic subtext to tales of female werewolves. Little wonder that werewolves remain so appealing for teenage horror fans!

Miscellaneous

Various other snippets of science underpin other werewolf myths. As Harry Potter fans will know, Harry’s teacher Remus Lupin (note the name) used Wolfsbane Potion to keep his lycanthropy under control. Wolfsbane is in fact a very poisonous plant which was used by people throughout history to kill nuisance animals, including wolves.

Elsewhere, the idea that a silver bullet can kill a werewolf is likely related to the anti-bacterial properties of silver as an element. And the super-human strength or speed exhibited by werewolves is probably just a simple reflection of the remarkable endurance and tracking ability of wolves in inhospitable environments.

So it seems unlikely you will encounter a real werewolf this Halloween. But, just in case, best stay on the road and keep clear of the moors. And beware of the moon

Paradoxical Hypertrichosis Associated with Laser and Light Therapy for Hair Removal: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

American Journal of Clinical Dermatology volume 22, pages615–624 (2021)

Background

Paradoxical hypertrichosis (PH) is an uncommon, poorly understood adverse effect associated with laser or intense pulsed light treatment for hair removal.

Objective

The objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine Paradoxical hypertrichosis (PH) prevalence and associated risk factors.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies evaluating hair removal with lasers or intense pulsed light. Primary outcome was Paradoxical hypertrichosis (PH) prevalence. Meta-regression and subgroup analysis were used to investigate associations among treatment modality, patients’ characteristics, and Paradoxical hypertrichosis (PH).

Results

Included were 9733 patients in two randomized controlled trials and 20 cohort studies (three prospective and 17 retrospective). Pooled Paradoxical hypertrichosis (PH) prevalence was 3% (95% confidence interval 1–6; I2 = 97%). Paradoxical hypertrichosis (PH) was associated with a face or neck anatomic location, and occurred in only 0.08% of non-facial/neck cases. Treatment modality and interval between treatments had no effect on the Paradoxical hypertrichosis (PH) rate. There were insufficient data to determine the association between sex and skin type to Paradoxical hypertrichosis (PH). In three out of four studies, Paradoxical hypertrichosis (PH) gradually improved with continued therapy.

Conclusions

Based primarily on cohort studies, Paradoxical hypertrichosis (PH) occurs in 3% of patients undergoing hair removal with lasers or intense pulsed light, yet rarely outside the facial/neck areas. Treatment modality does not seem to be a contributing factor. Continuation of treatment in areas with Paradoxical hypertrichosis (PH) may be the most appropriate treatment.

spacer

spacer

Medication Mix-Up Leaves 17 Children Suffering From ‘Werewolf Syndrome’

Thanks to distribution error at Spanish laboratory, anti-baldness medication was sold as acid reflux treatment. (That is their story and they are sticking to it. We know it is Bullshit!)

By Meilan Solly

SMITHSONIAN.COM

AUGUST 30, 2019